[i]

A SAILOR’S LIFE

[ii]

[iv]

Photographed by

Her Highness the Râni of Sarawak

[v]

BY

ADMIRAL OF THE FLEET

THE HON. SIR HENRY KEPPEL

G.C.B., D.C.L.

VOL. II

London

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1899

All rights reserved

[vii]

| CHAPTER XXXII | |

| PAGE | |

| Dido | 1 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII | |

| Dido: Second Expedition | 10 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV | |

| Dido | 22 |

| CHAPTER XXXV | |

| England | 30 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI | |

| Shore Time—Study Steam | 38 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII | |

| Shore Time | 50 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII | |

| The Mæander | 65 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX [viii] | |

| Mæander—Cruising | 92 |

| CHAPTER XL | |

| Mæander—Cruising in the Sulu Sea | 106 |

| CHAPTER XLI | |

| Mæander—Hong Kong | 115 |

| CHAPTER XLII | |

| In Eastern Seas | 124 |

| CHAPTER XLIII | |

| Mæander | 144 |

| CHAPTER XLIV | |

| En route to Sydney | 151 |

| CHAPTER XLV | |

| Sydney to Hobart Town | 153 |

| CHAPTER XLVI | |

| Sydney | 164 |

| CHAPTER XLVII | |

| Mæander | 190 |

| CHAPTER XLVIII [ix] | |

| At Home | 201 |

| CHAPTER XLIX | |

| Shore Time | 205 |

| CHAPTER L | |

| St. Jean d’ Acre | 208 |

| CHAPTER LI | |

| St. Jean d’ Acre—Cruising | 215 |

| CHAPTER LII | |

| The Baltic Fleet | 223 |

| CHAPTER LIII | |

| The Bombardment of Bomarsund | 233 |

| CHAPTER LIV | |

| St. Jean d’ Acre | 238 |

| CHAPTER LV | |

| The Crimea | 245 |

| CHAPTER LVI | |

| St. Jean d’ Acre | 261 |

| CHAPTER LVII [x] | |

| Second Expedition to Kertch | 270 |

| CHAPTER LVIII | |

| Naval Brigade | 276 |

| CHAPTER LIX | |

| Trenches—Before Sevastopol | 288 |

| CHAPTER LX | |

| The Redan | 297 |

| CHAPTER LXI | |

| After Fall of Sevastopol | 304 |

| CHAPTER LXII | |

| Arrival from Crimea—Thence in Colossus—Shore Time | 312 |

| CHAPTER LXIII | |

| The Raleigh | 325 |

| CHAPTER LXIV | |

| The Raleigh | 330 |

| CHAPTER LXV | |

| Cape to China | 333 |

| INDEX | |

[xi]

| SUBJECT | ARTIST | PAGE |

|---|---|---|

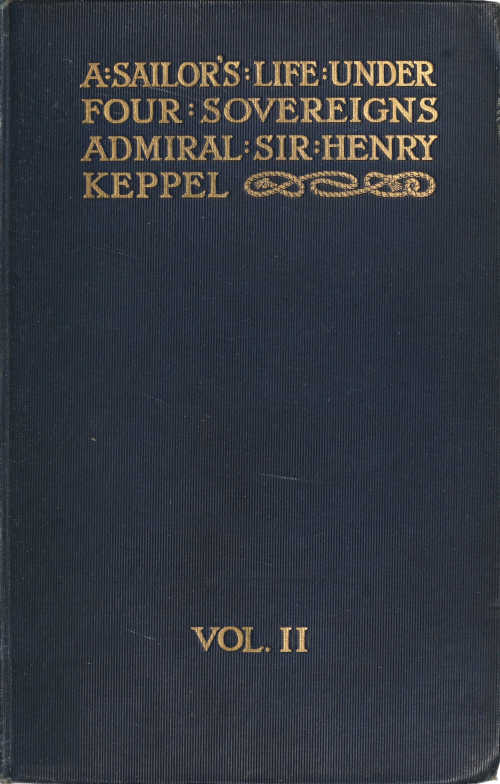

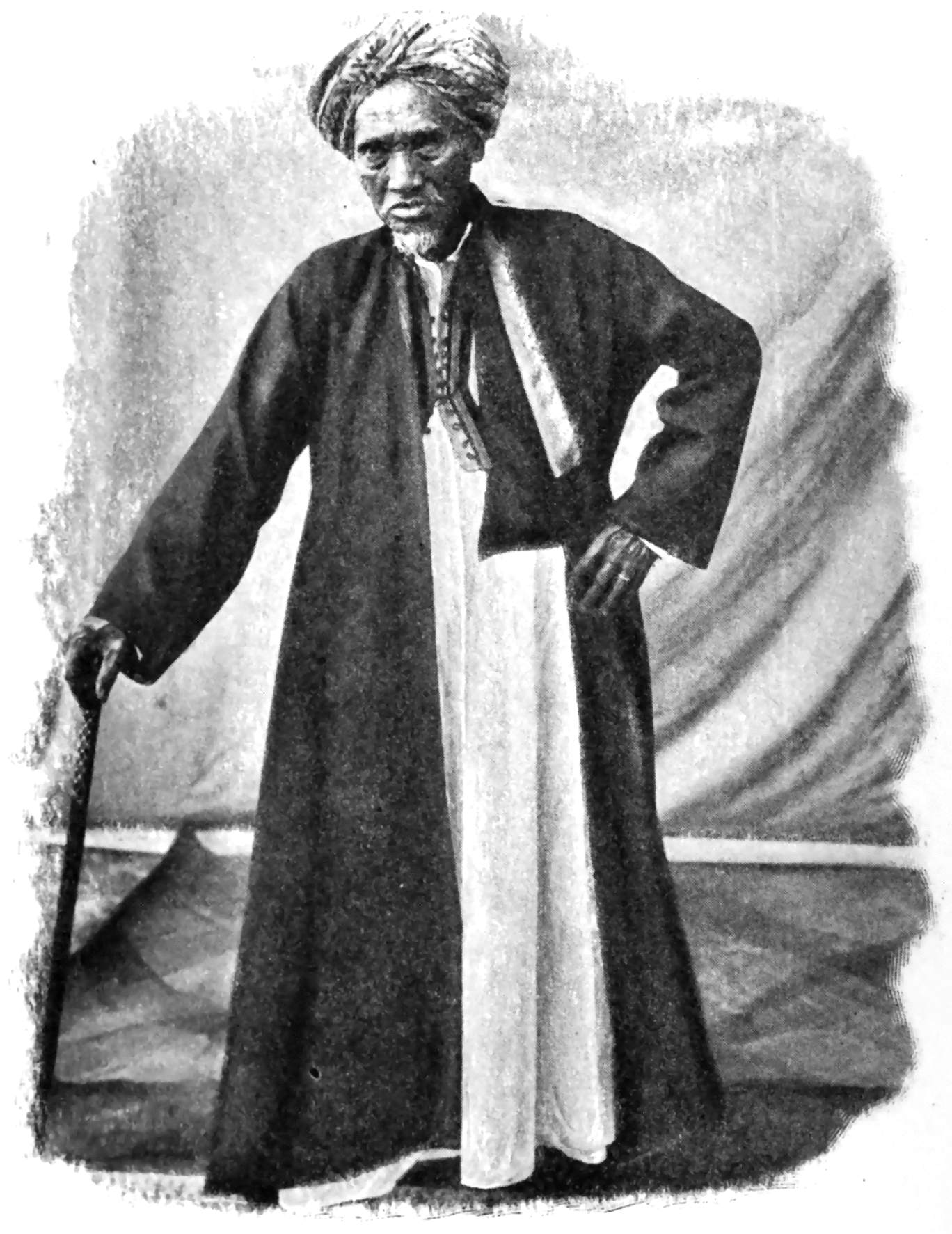

| A Hadji | Photographed by Her Highness the Râni of Sarawak | Frontispiece |

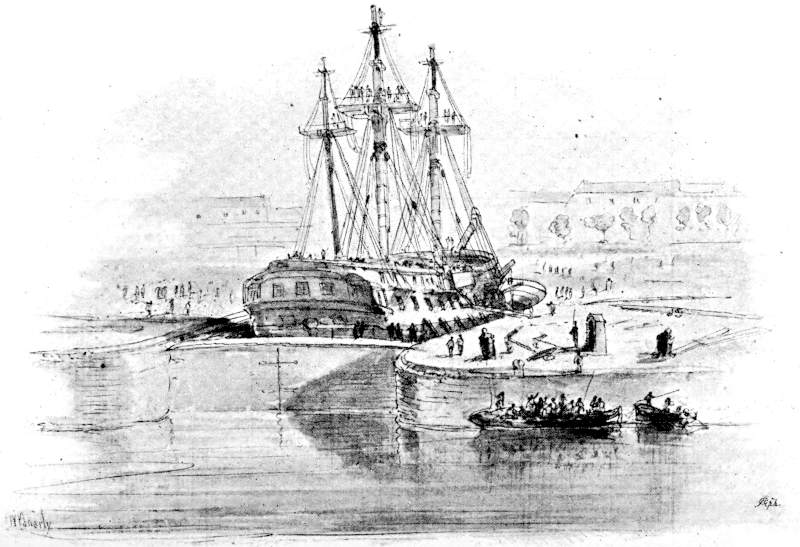

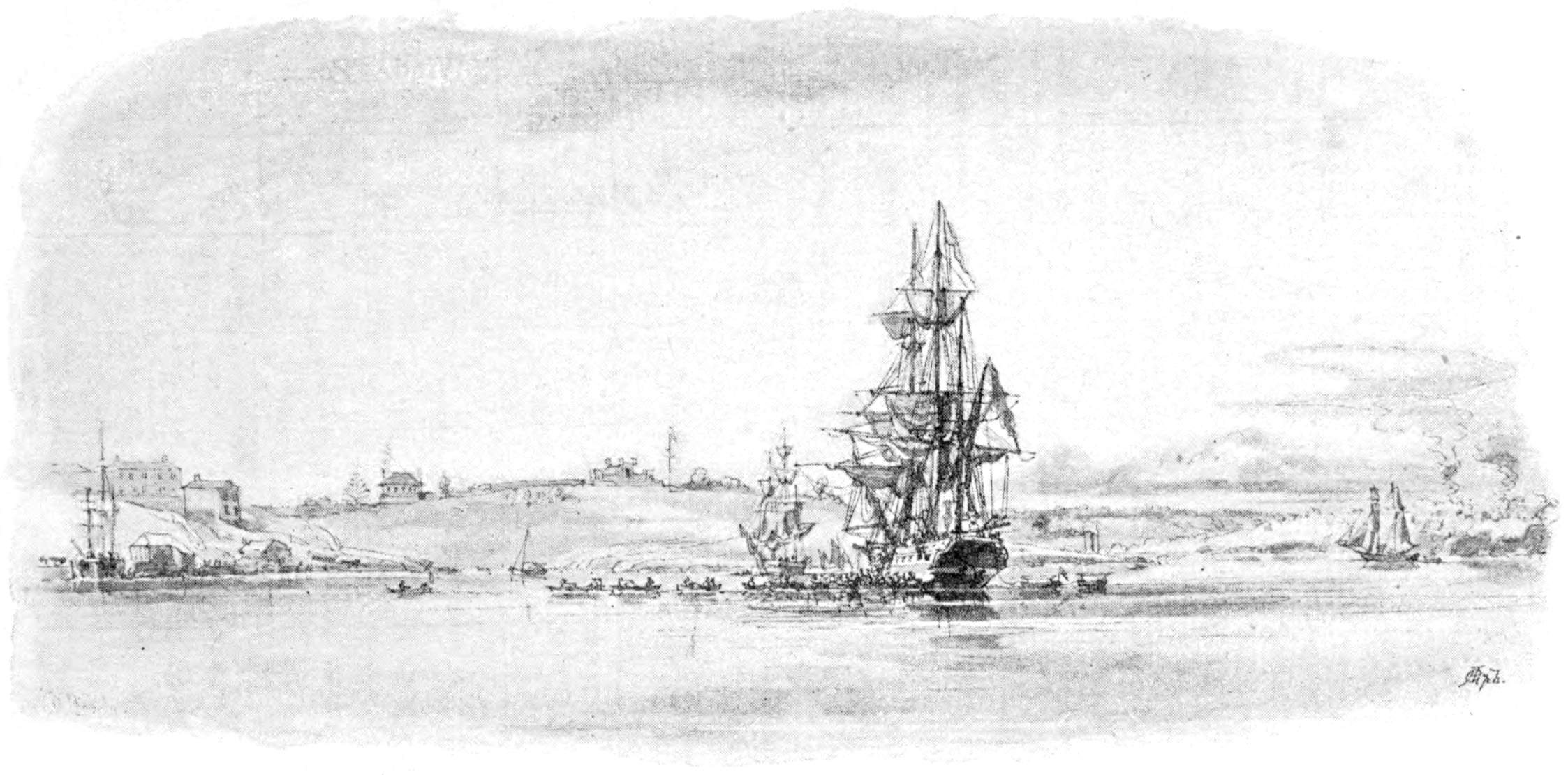

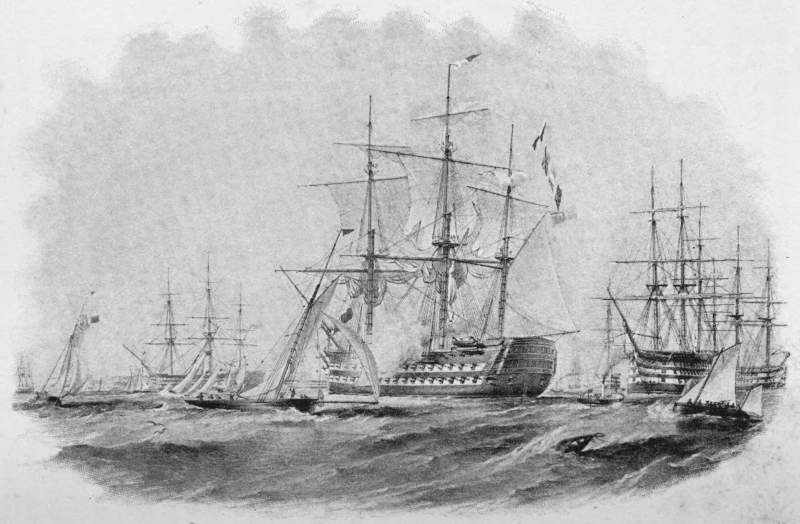

| Mæander Fitting | Sir Oswald Brierly | 66 |

| Mæander leaving Plymouth | ” ” | 68 |

| “The Bishop” | From a photograph | 71 |

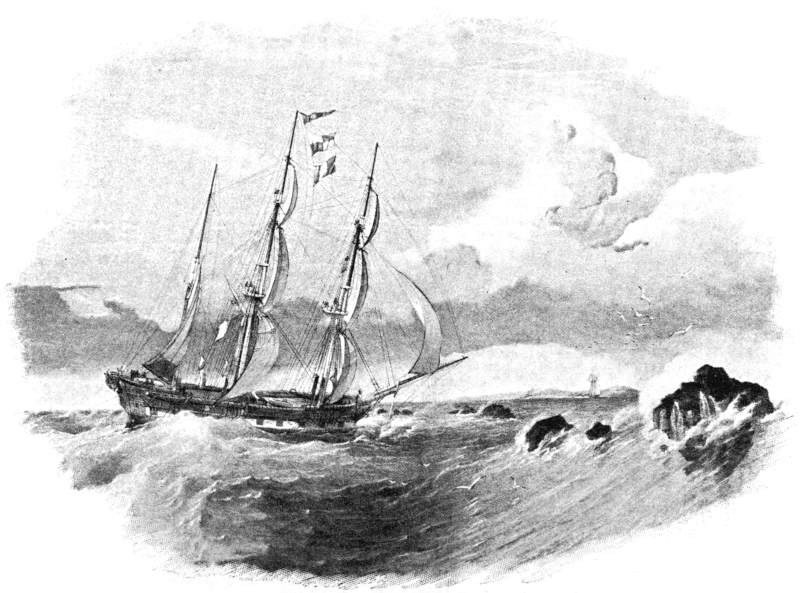

| Mæander hove to | Sir Oswald Brierly | 74 |

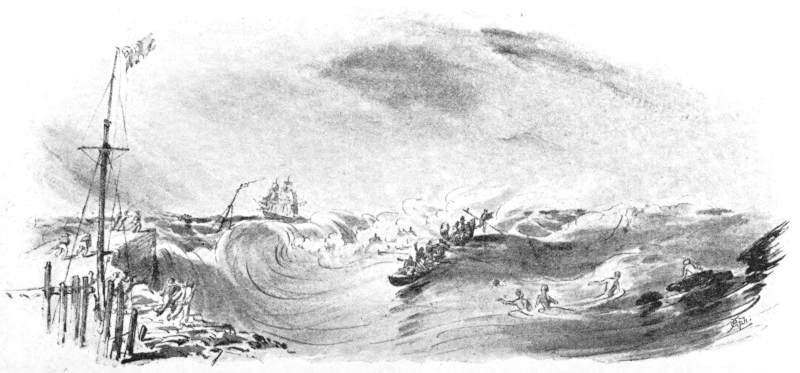

| Comber in Danger | ” ” | 75 |

| New Harbour, Singapore | ” ” | 78 |

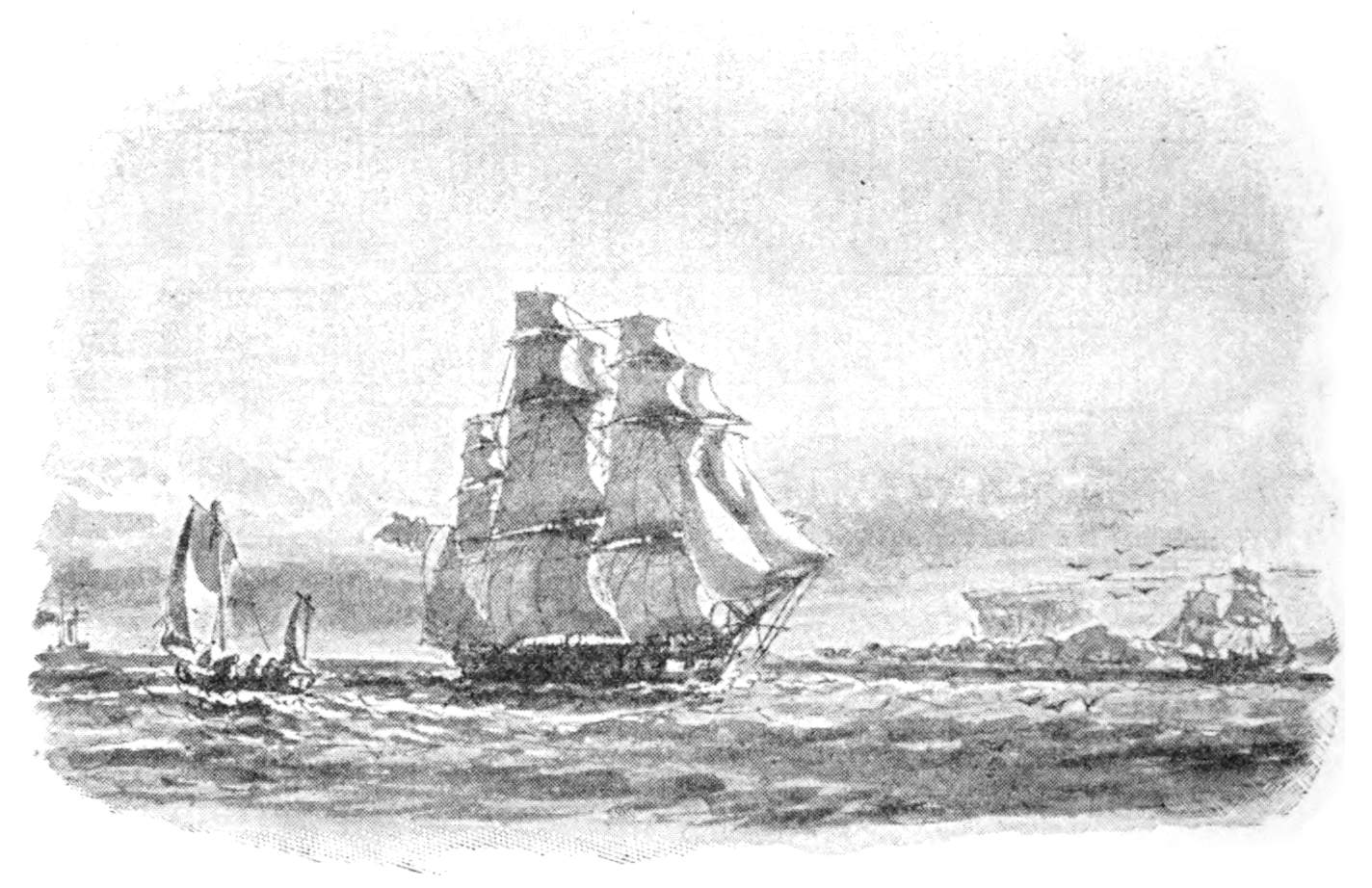

| All Sail set | ” ” | 83 |

| Mæander passing astern of Hastings | ” ” | 89 |

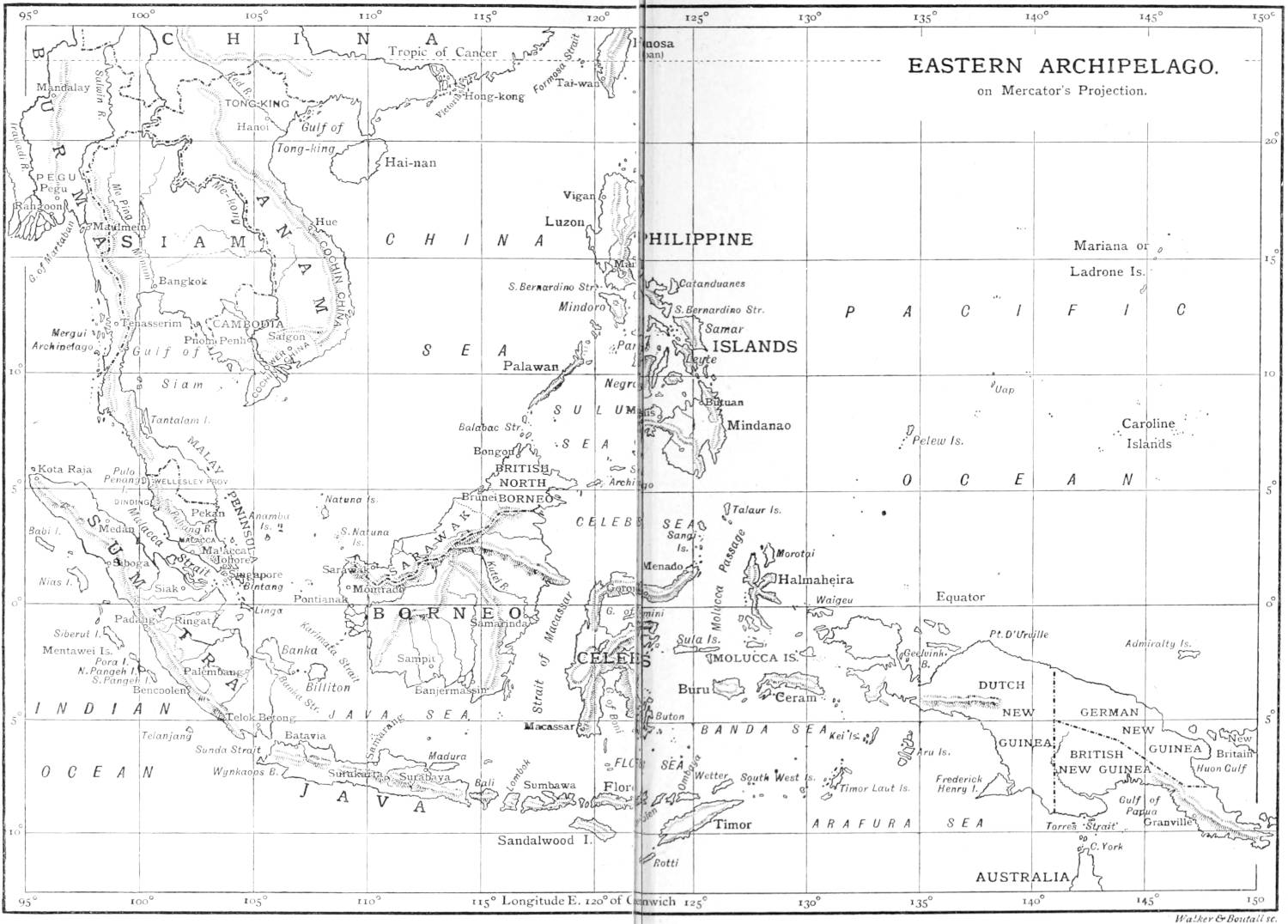

| Map—Eastern Archipelago | 92 | |

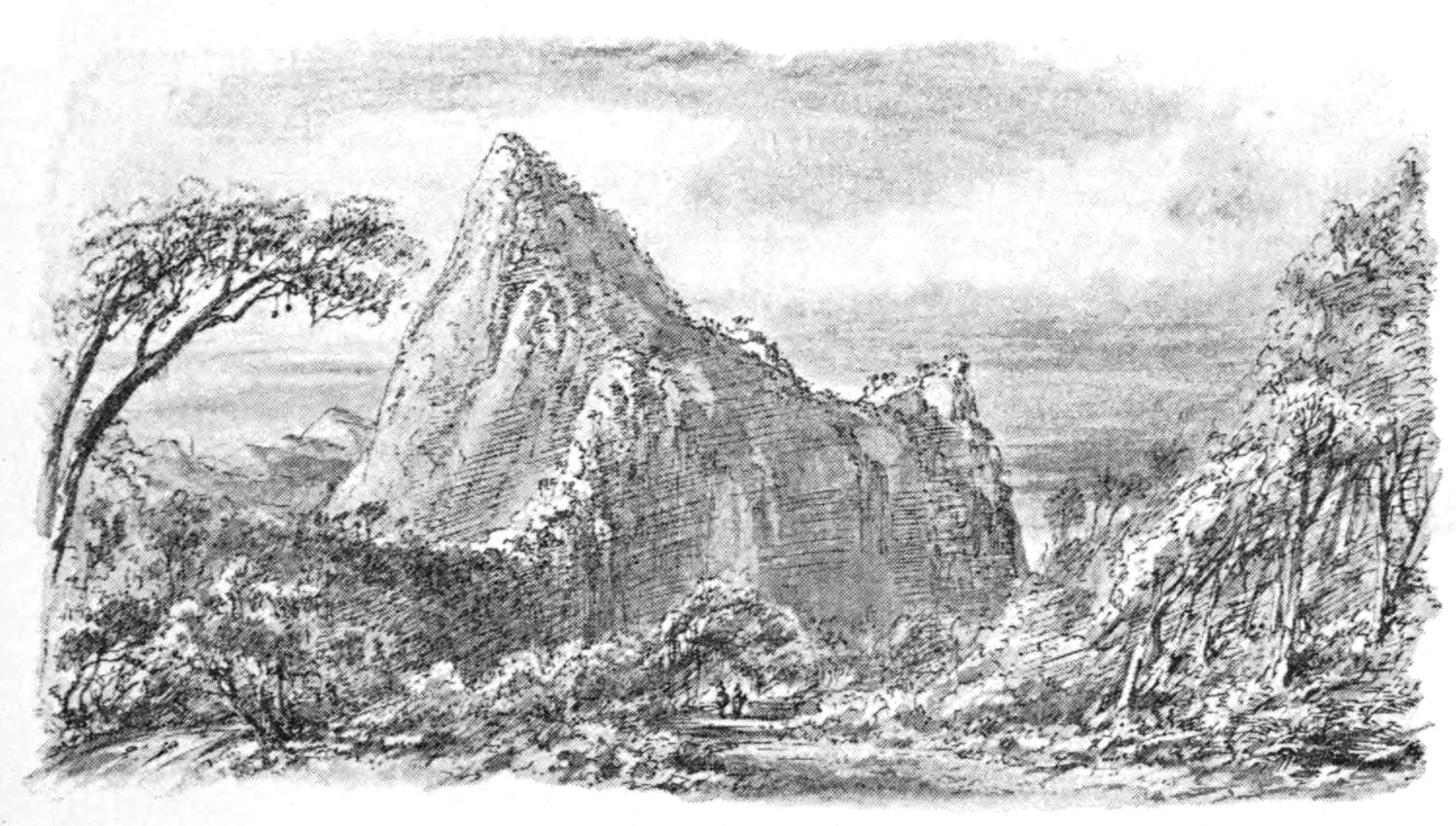

| Kina-Balu, N. Borneo | ” ” | 95 |

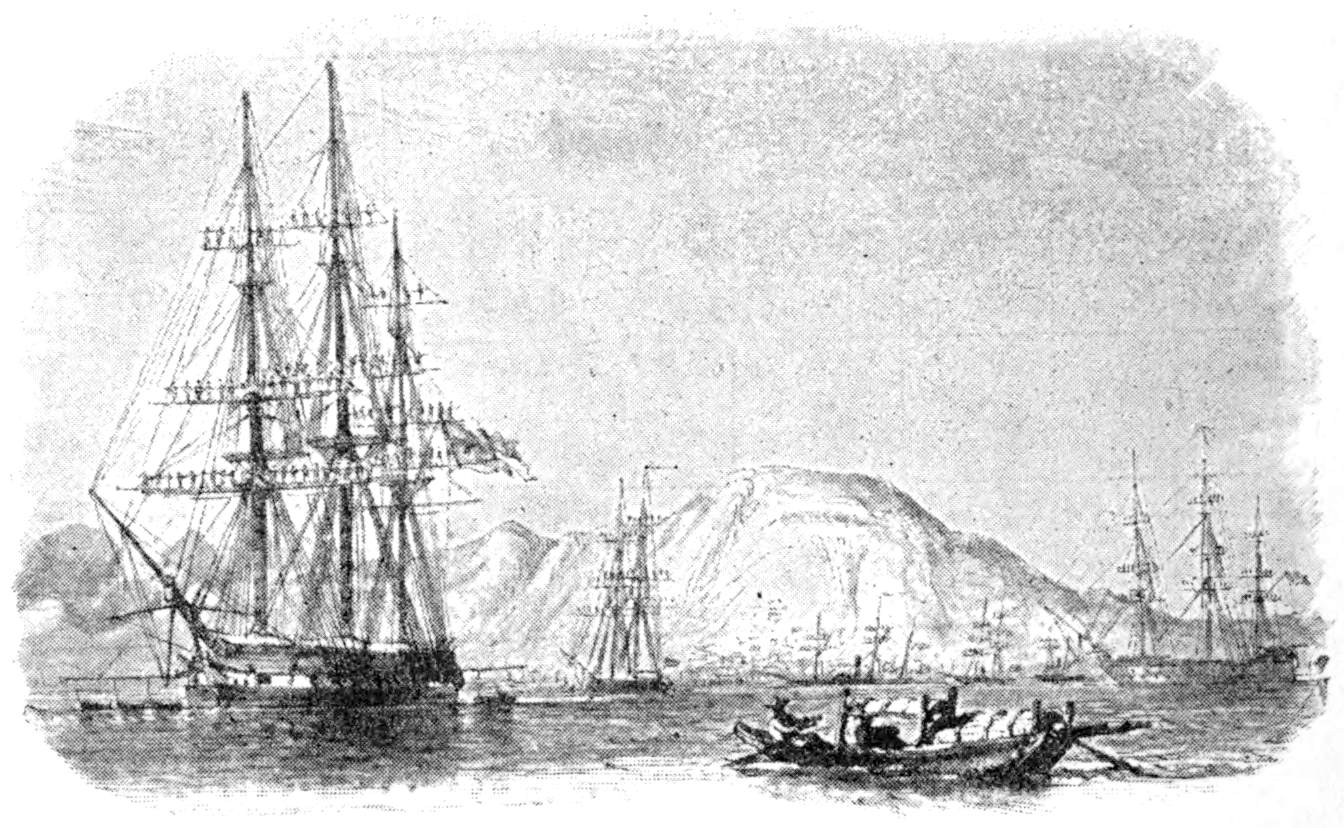

| Mæander, Hong Kong. Manned Yards on Departure of Sir Francis Collier | ” ” | 114 |

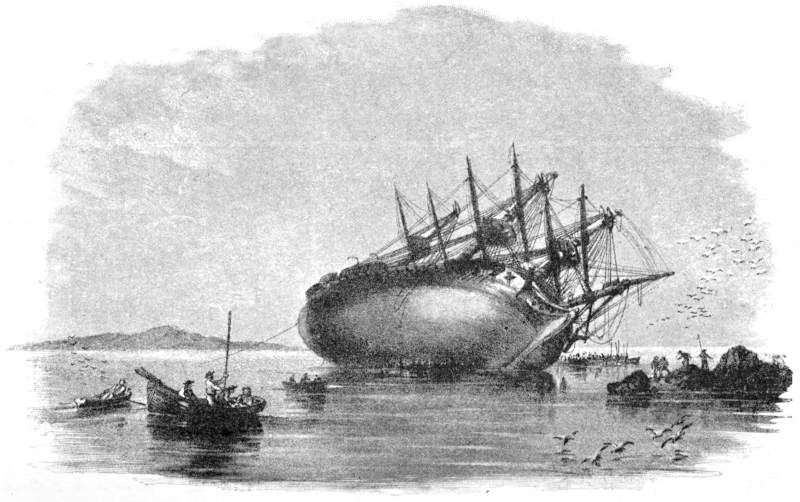

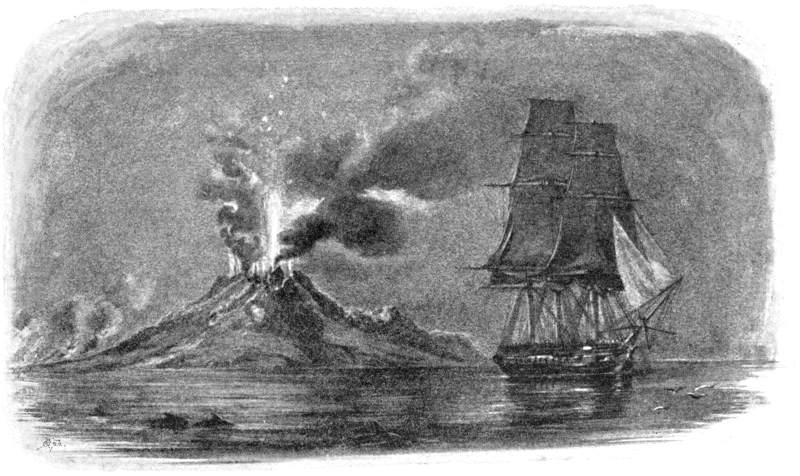

| A Spanish Galleon | ” ” | 124 |

| Mæander on Shore | ” ” | 126 |

| Comba | ” ” | 133 |

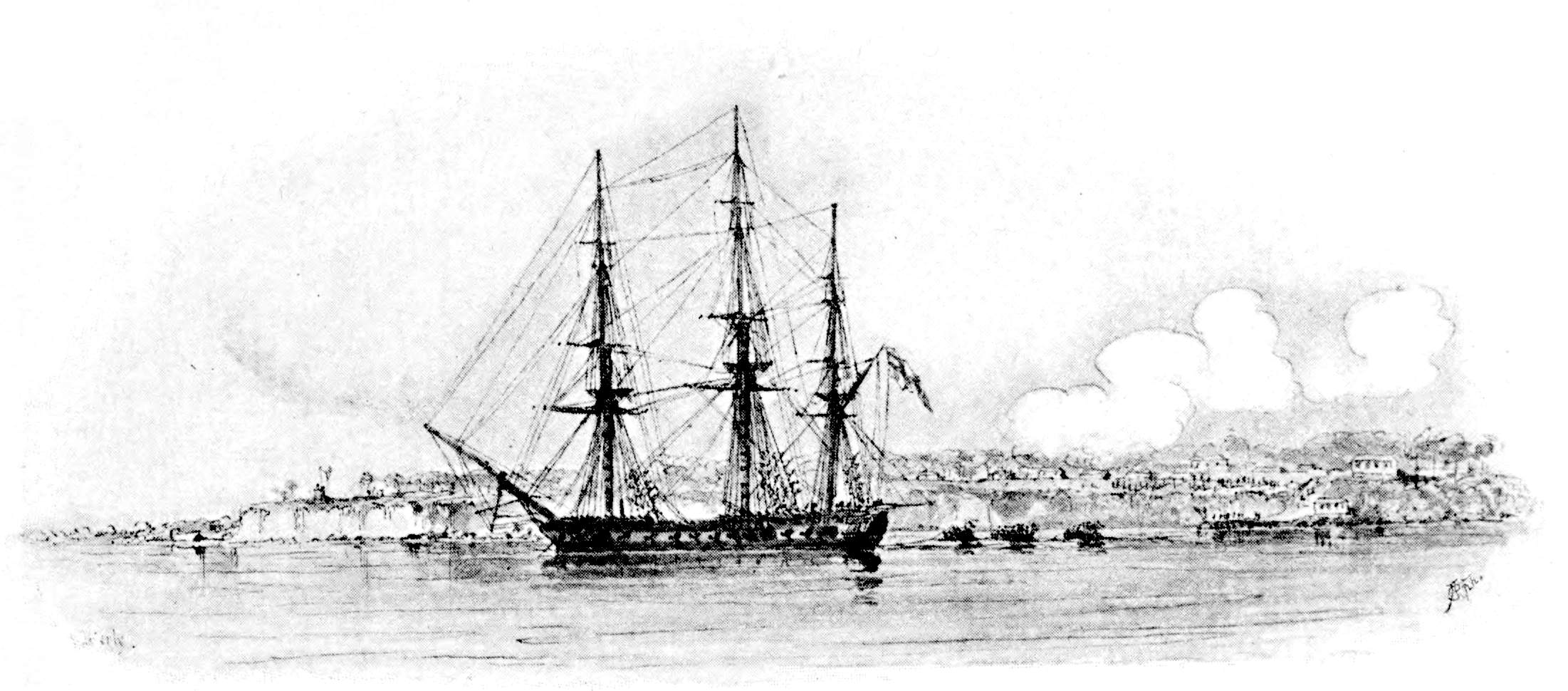

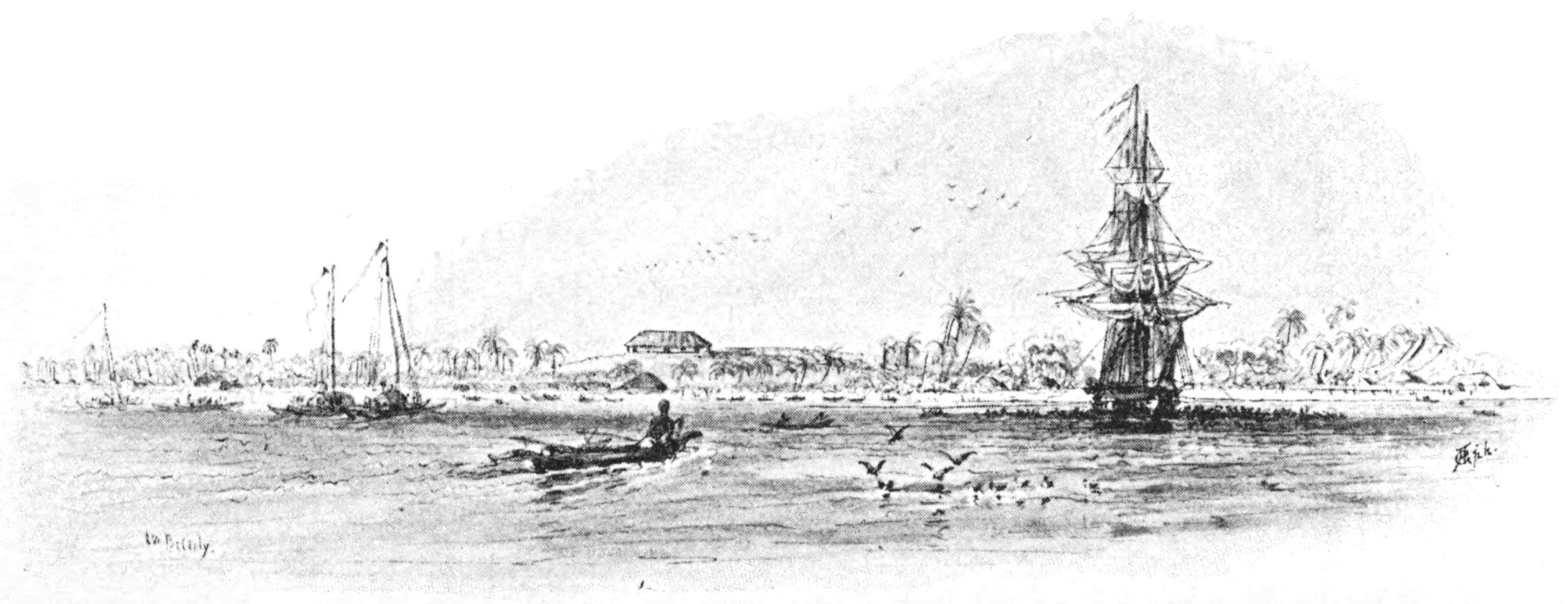

| Mæander off Port Essington | ” ” | 135 |

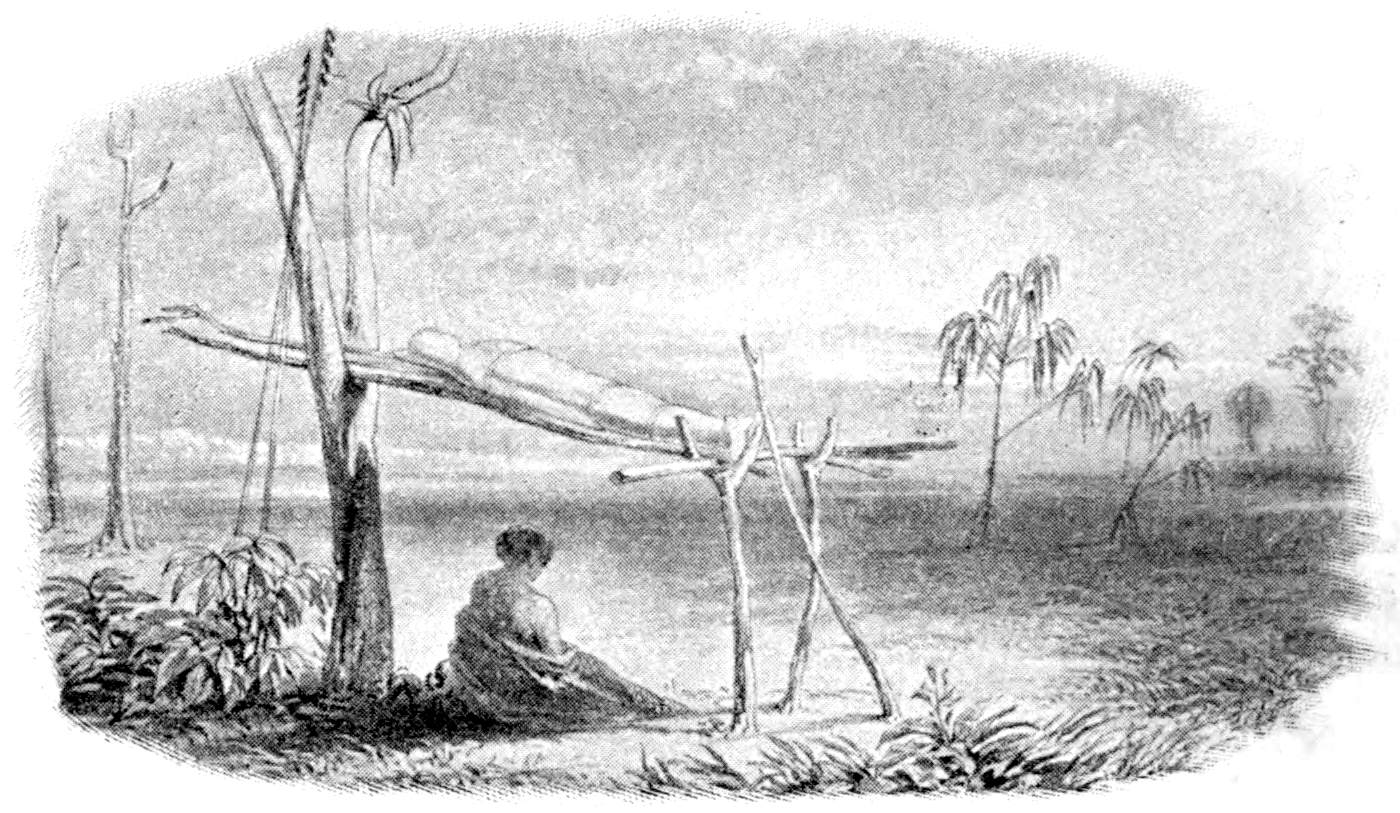

| An Australian Grave | ” ” | 136 |

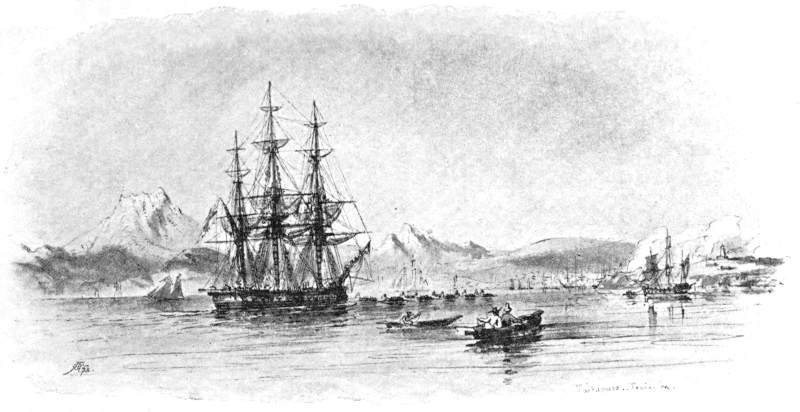

| Mæander at Sydney | ” ” | 154 |

| Sir Oswald Brierly | Nina Daly | 156 |

| Mæander at Hobart Town | Sir Oswald Brierly | 159 |

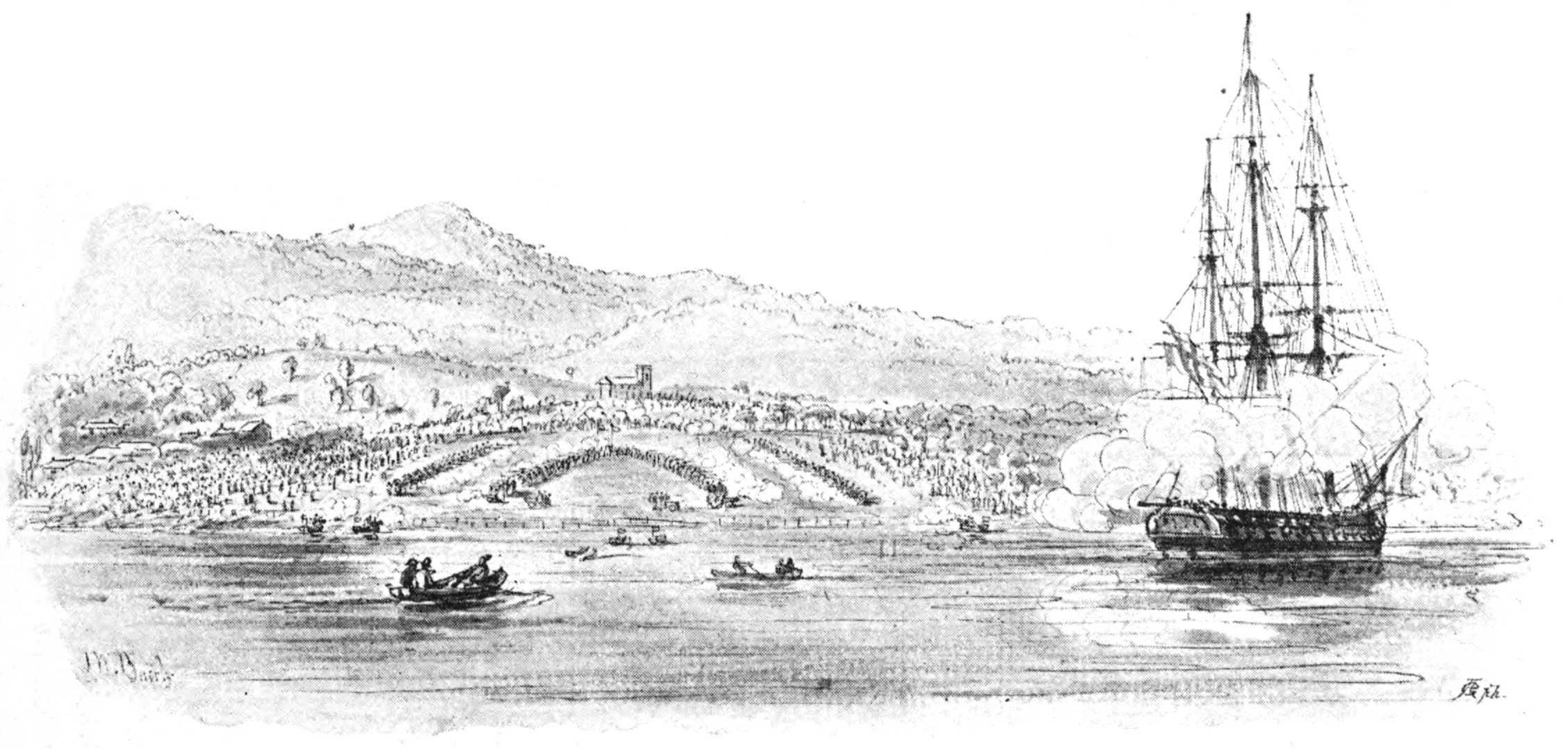

| The Sham Fight | ” ” | 161 |

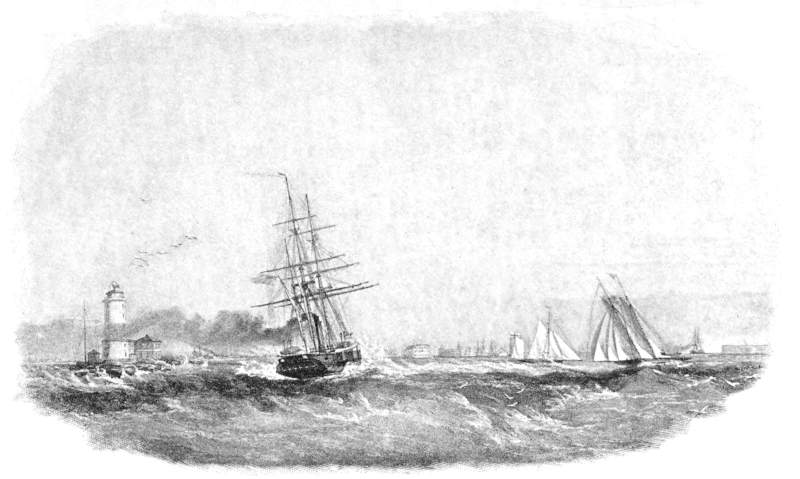

| Mæander between Sydney Heads | ” ” | 164 |

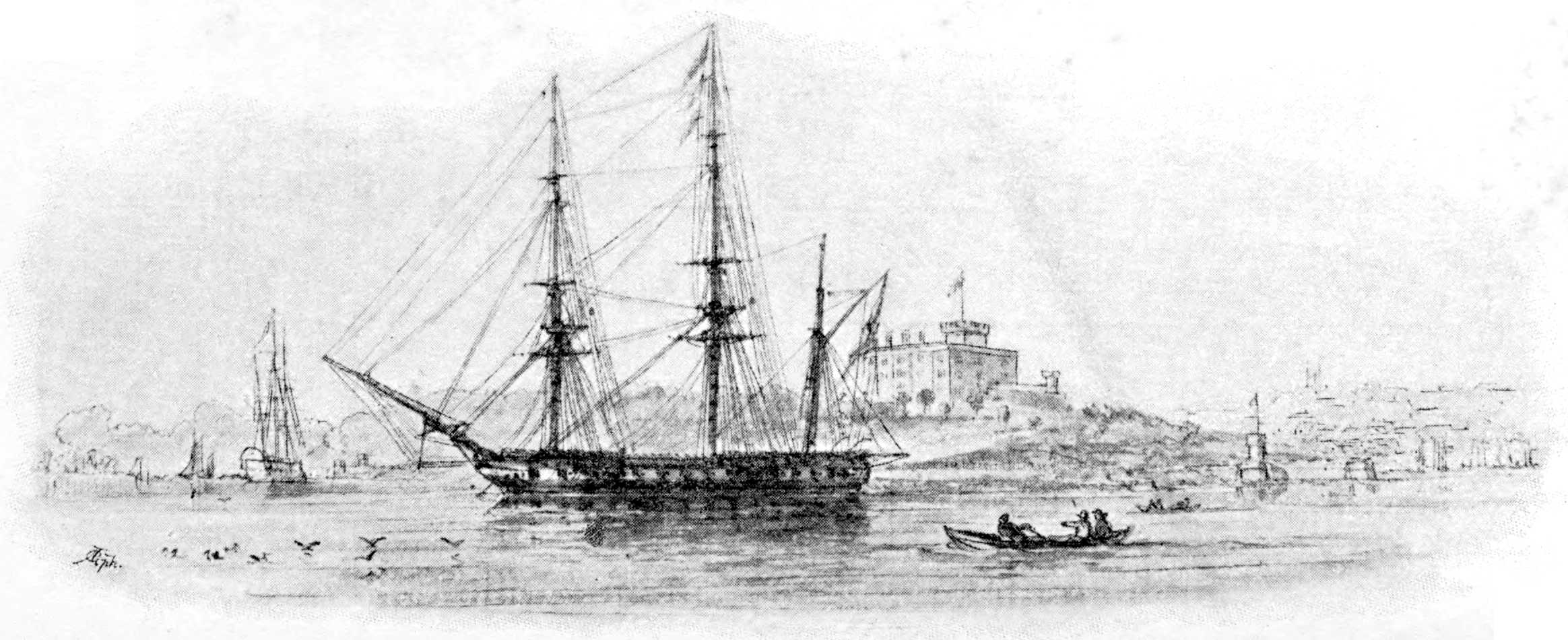

| The Rattlesnake | ” ” | 166 |

| Rescue by Convicts. Norfolk Island | ” ” | 168 |

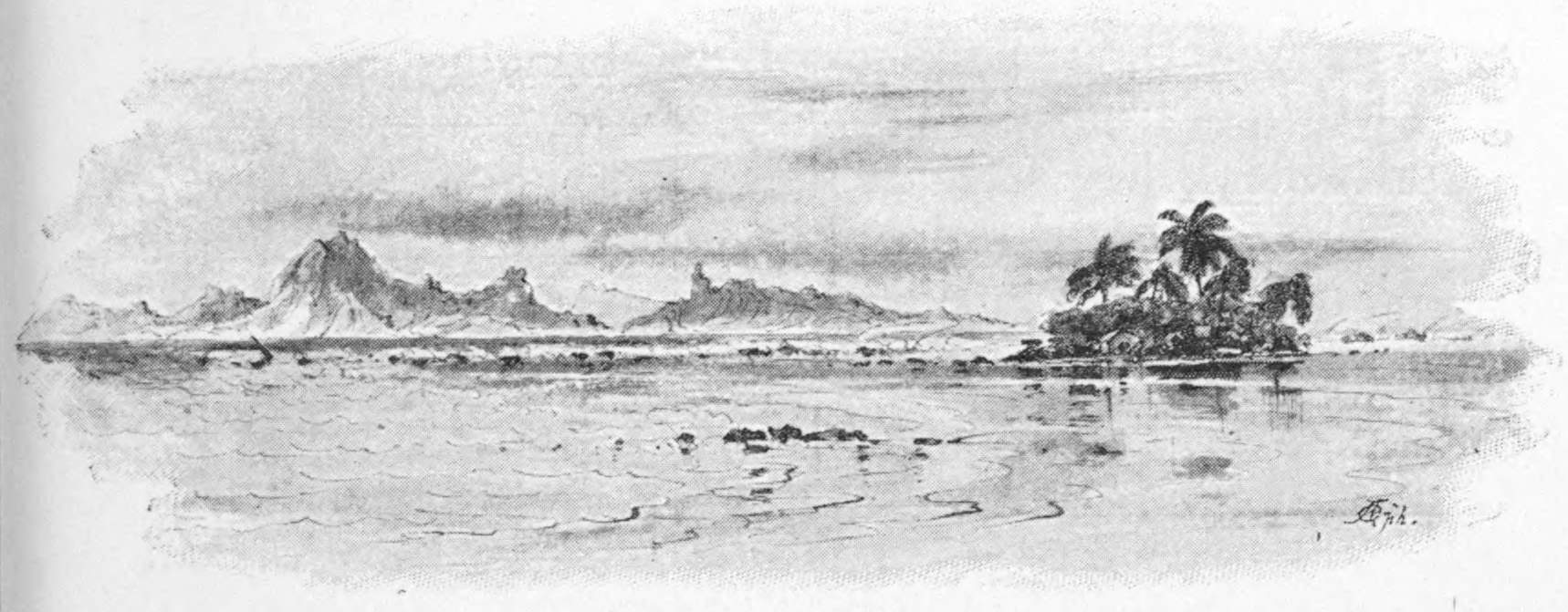

| A Coral Island | ” ” | 170 |

| A Stockade | ” ” | 172 |

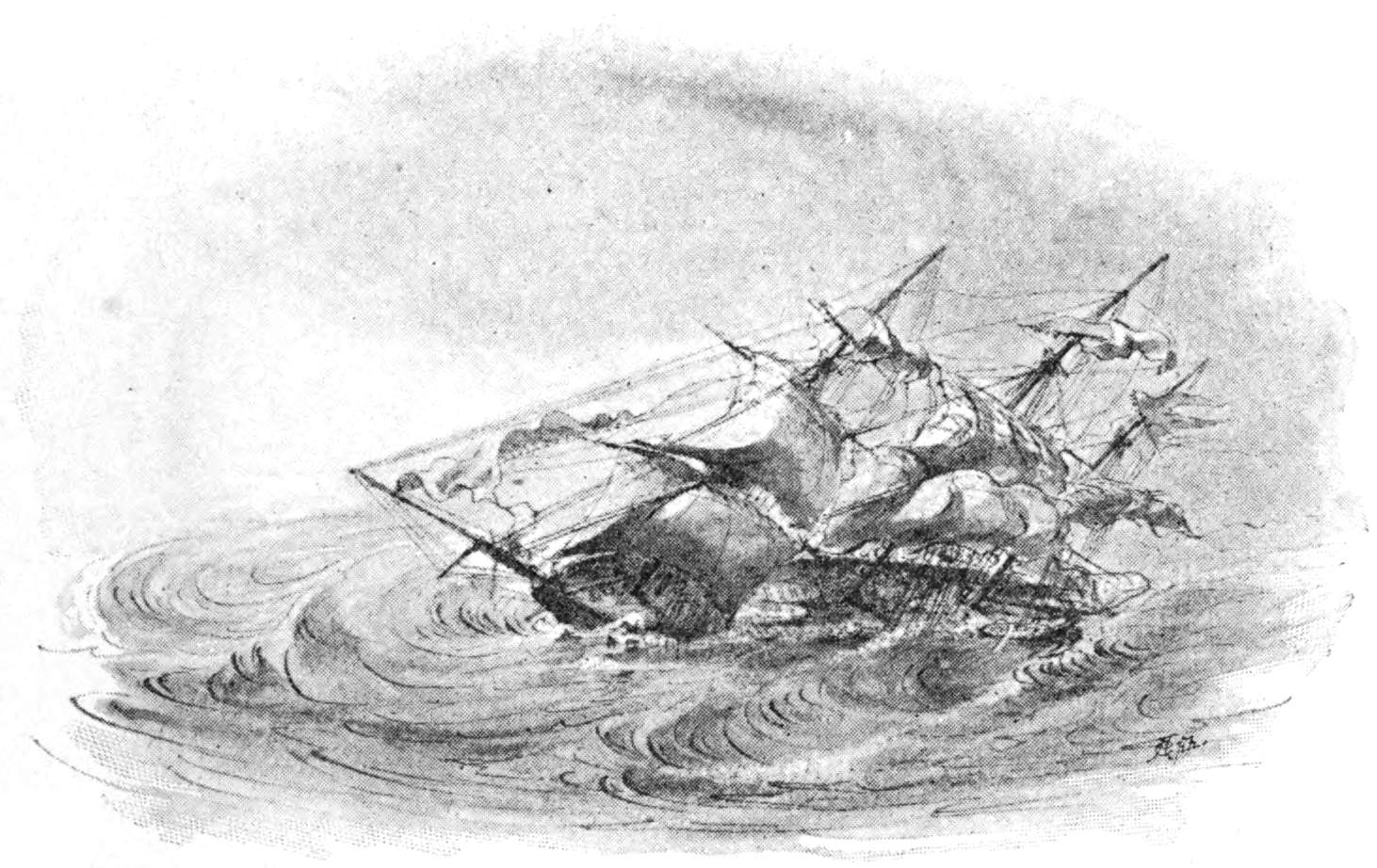

| Mæander in a Gale [xii] | Sir Oswald Brierly | 173 |

| Point Venus, Tahiti | ” ” | 174 |

| Tahiti Harbour | ” ” | 176 |

| Lieutenant George Bowyear | Nina Daly | 177 |

| Eimeo | Sir Oswald Brierly | 178 |

| Inland Scenery, Tahiti | ” ” | 179 |

| A Coral Atoll | ” ” | 181 |

| Mæander at Valparaiso | ” ” | 183 |

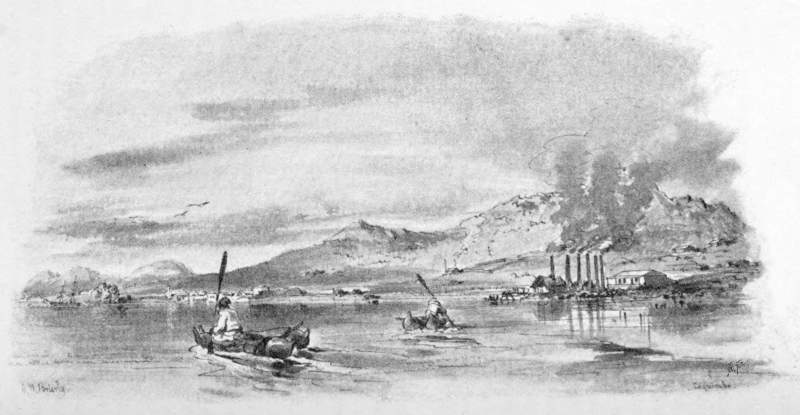

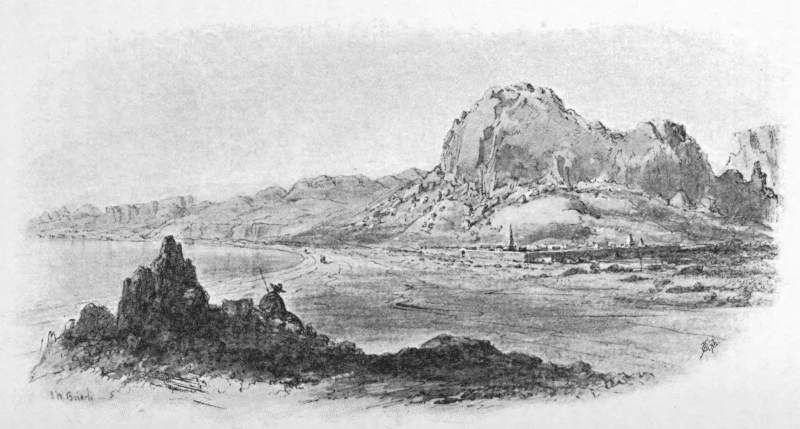

| Coquimbo | ” ” | 186 |

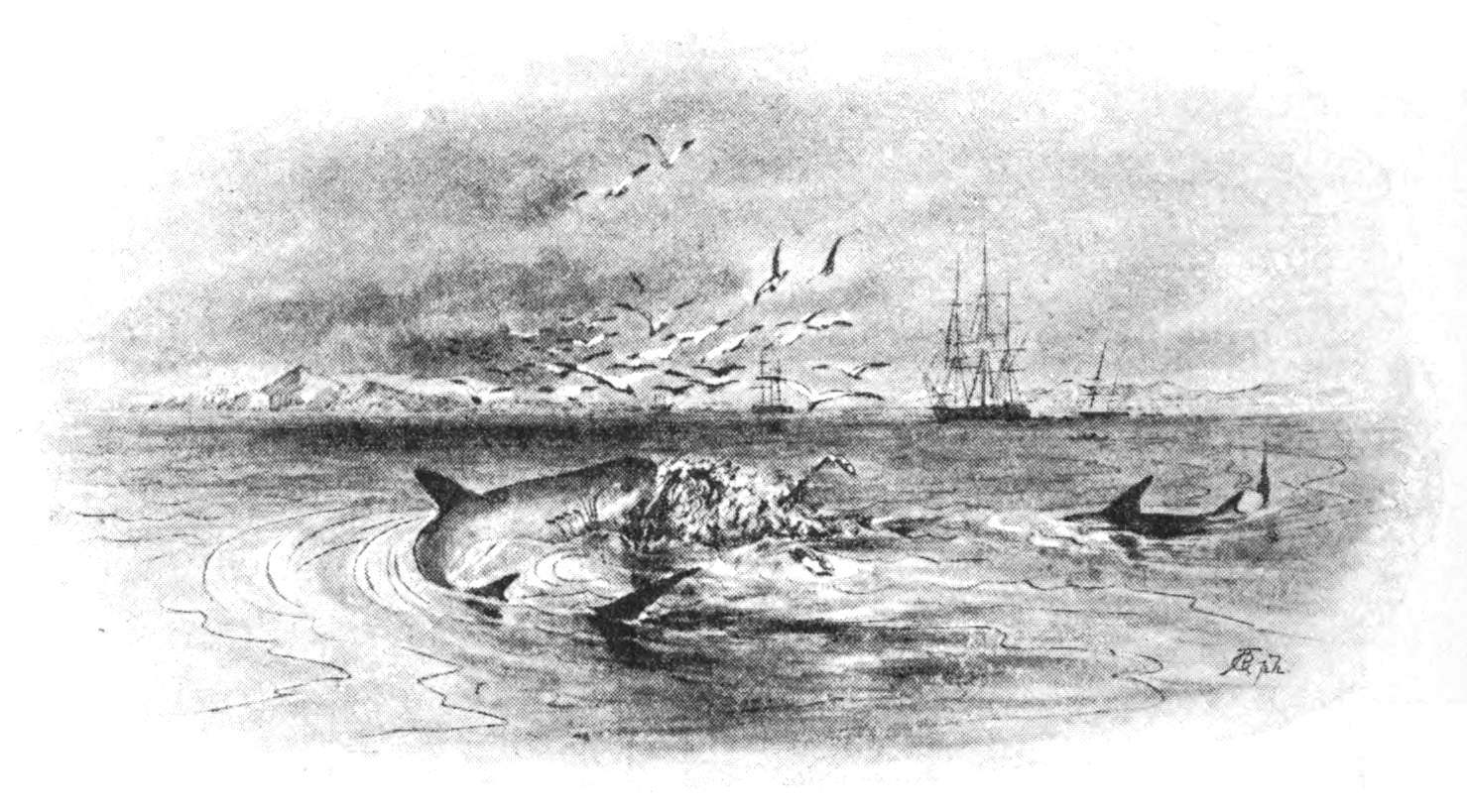

| Sharks at Mazatlan | ” ” | 188 |

| The Cemetery at Guyamas | ” ” | 192 |

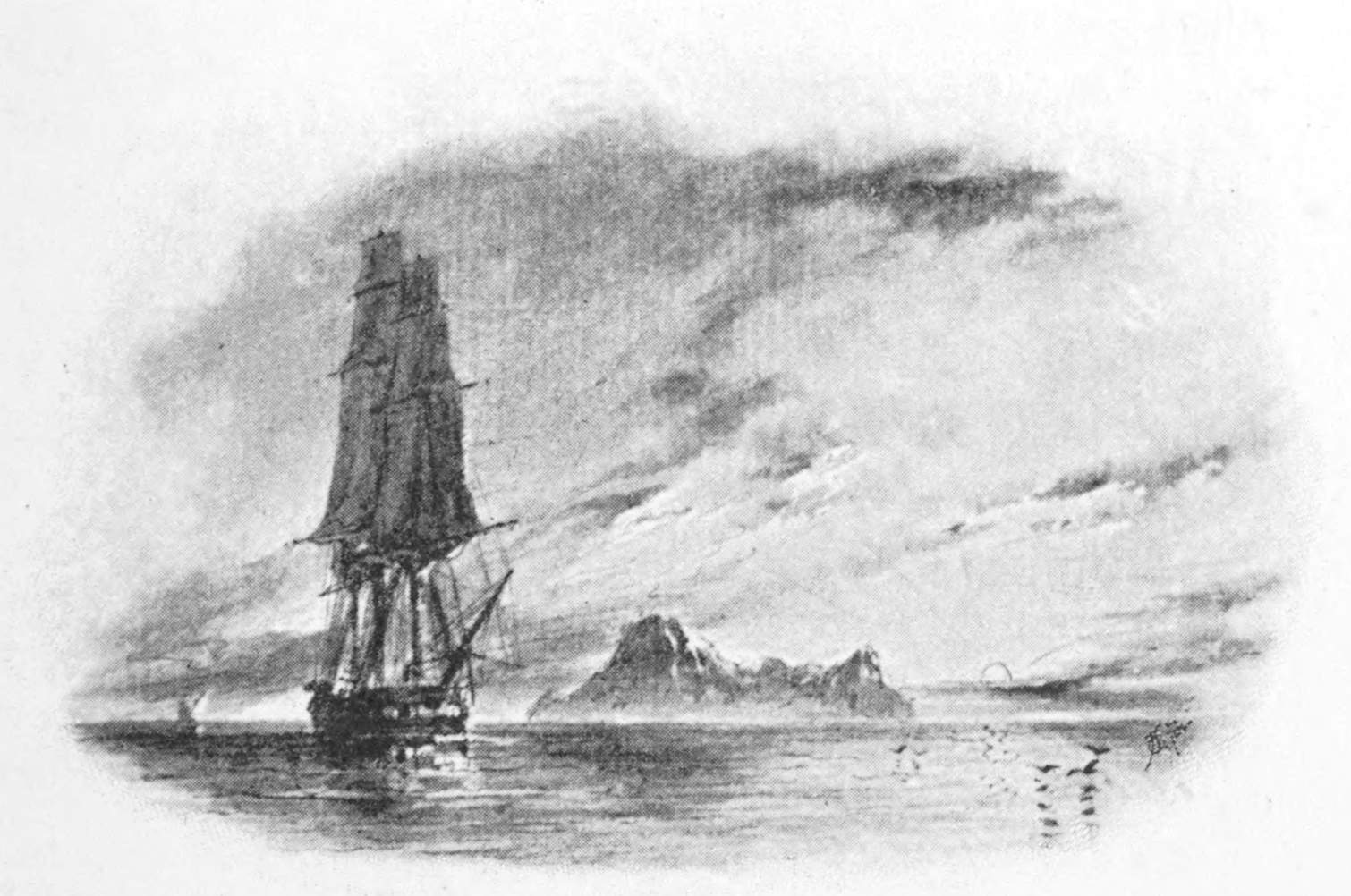

| In the Straits of Magellan | ” ” | 197 |

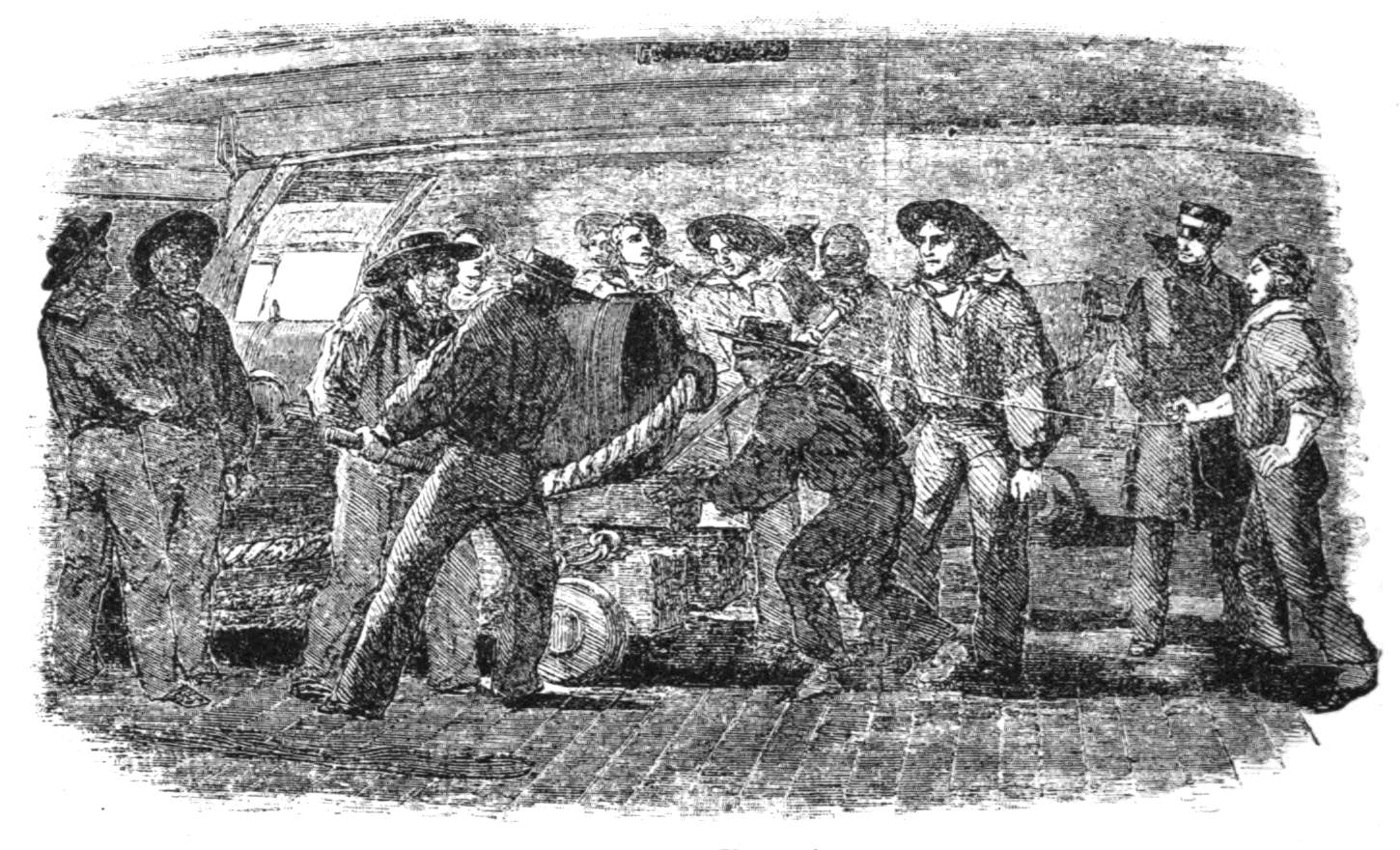

| Gunnery Exercise | ” ” | 216 |

| The St. Jean d’ Acre | ” ” | 222 |

| The Commander-in-Chief | Anon. | 227 |

| The Gondola Yacht off Tolbeacon Light | Sir Oswald Brierly | 229 |

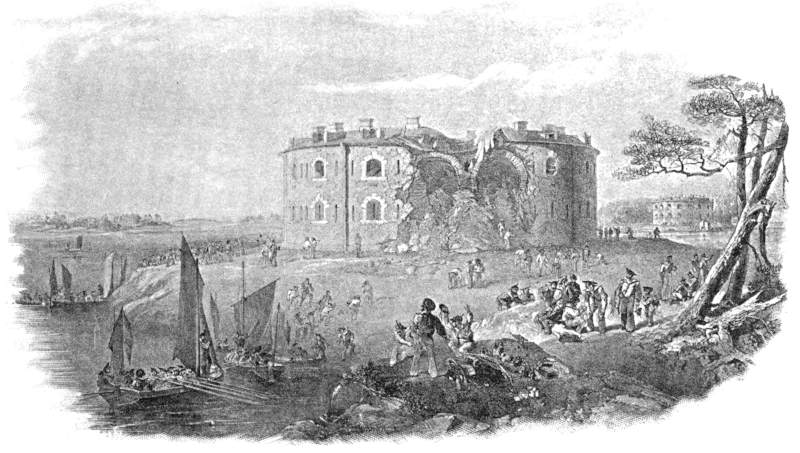

| Circular Fort—Bomarsund | ” ” | 237 |

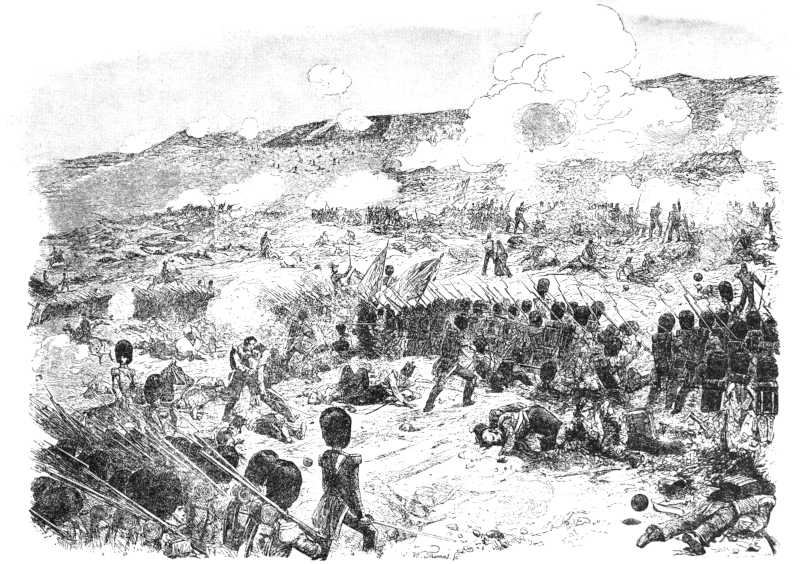

| The Battle of the Alma | “Illustrated London News” | 241 |

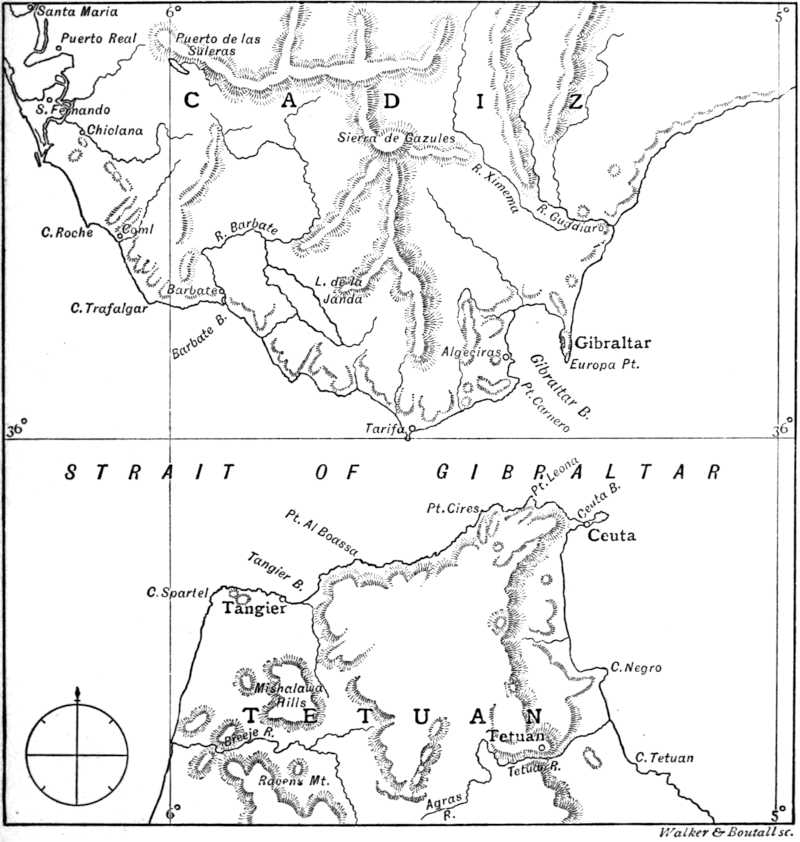

| Map—Strait of Gibraltar | 247 | |

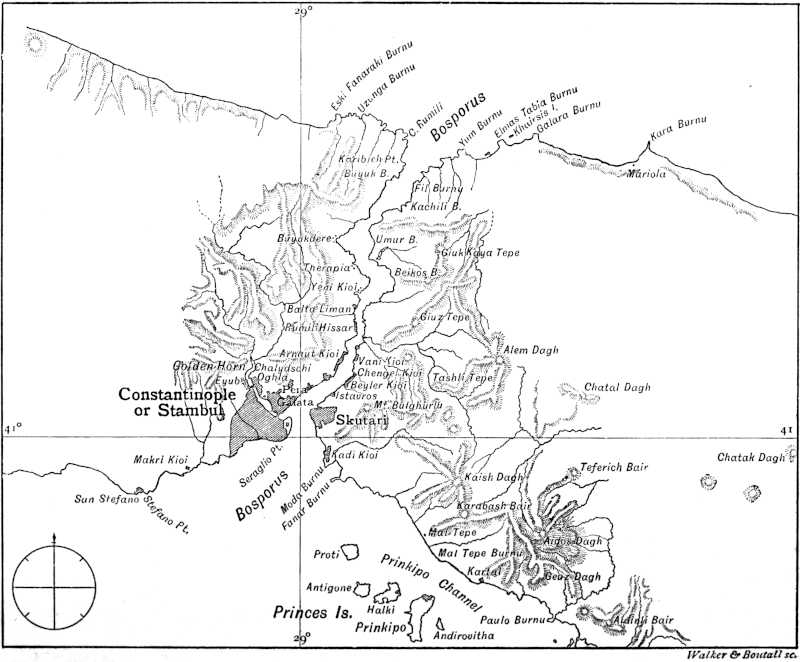

| Map—The Bosporus | 250 | |

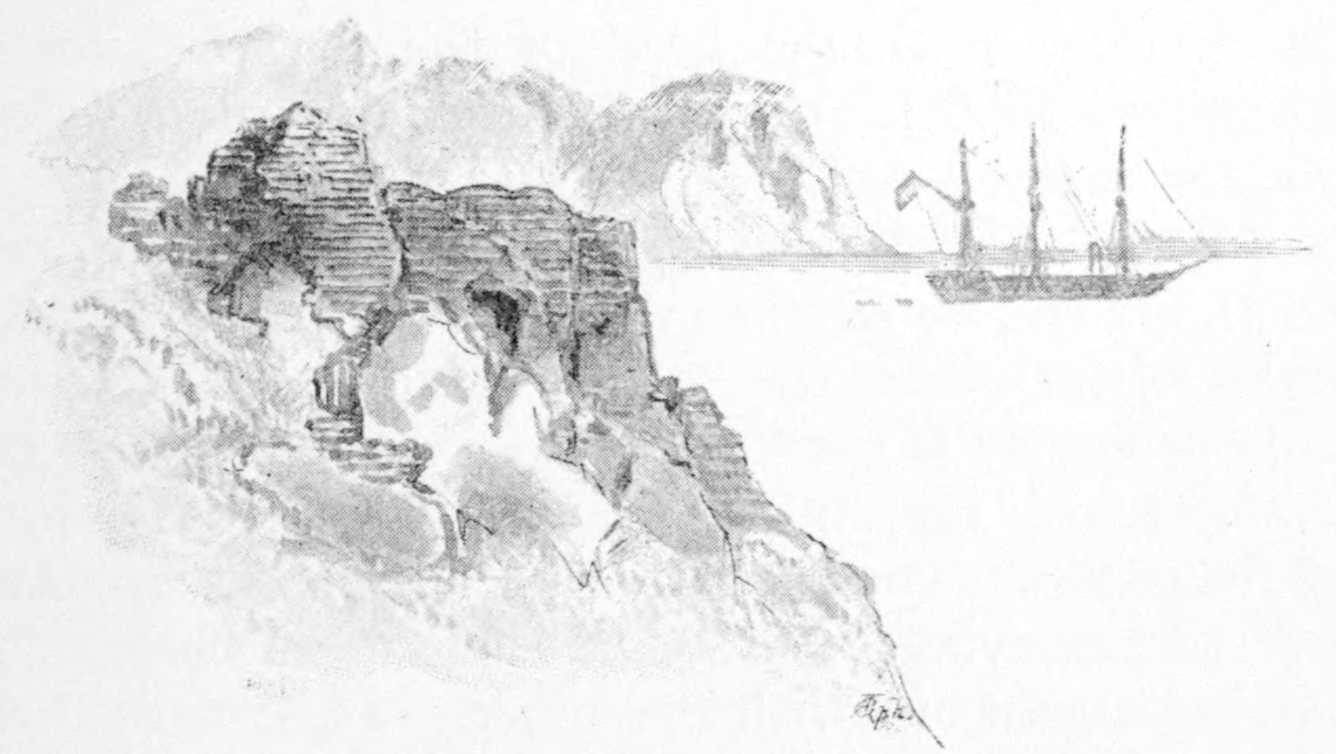

| St. Jean d’ Acre off Balaclava | Col. Hon. Sir W. Colville, K.C.V.O., C.B. | 251 |

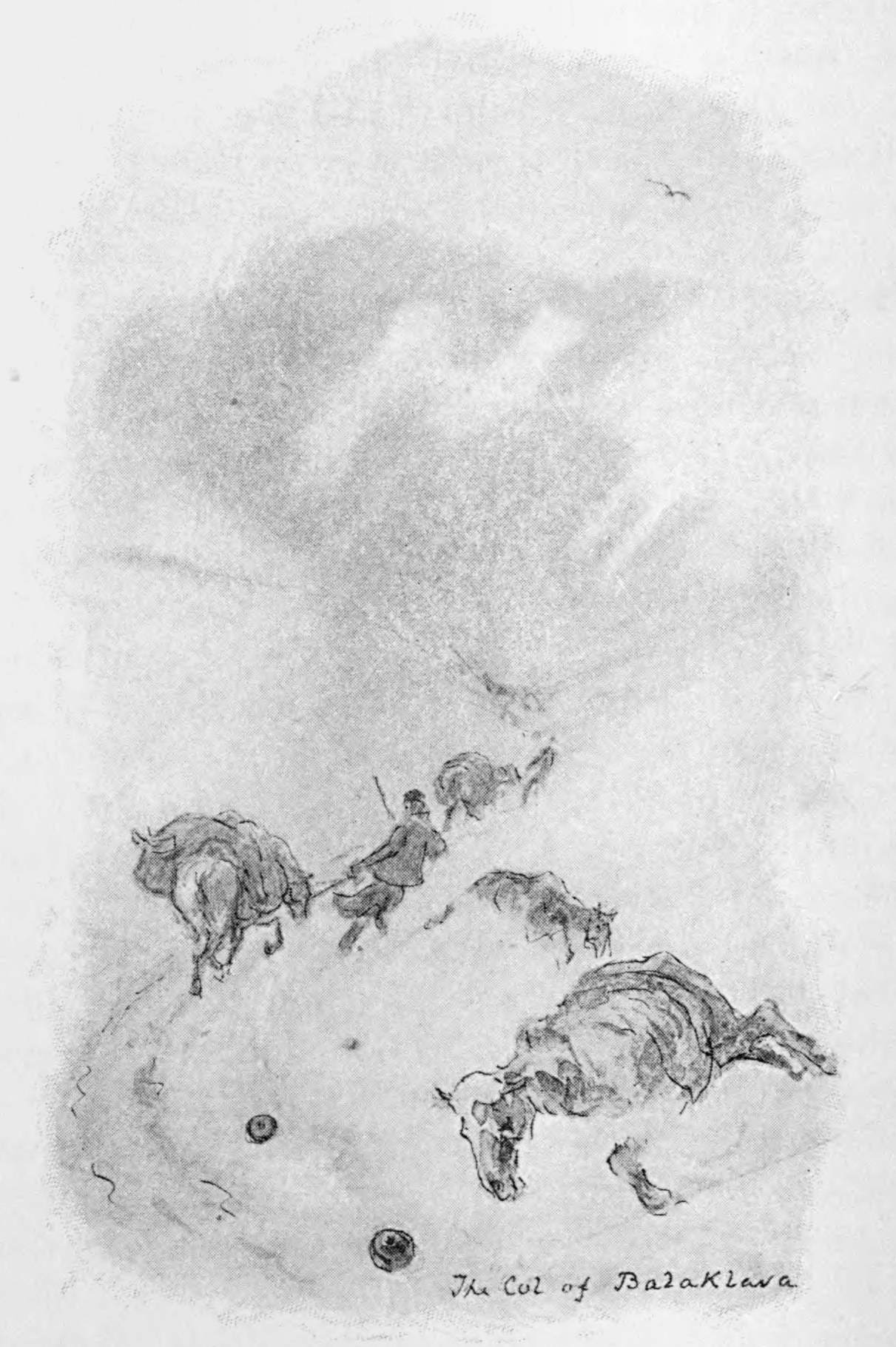

| “All the Way Up.” The Col of Balaclava | ” ” | 254 |

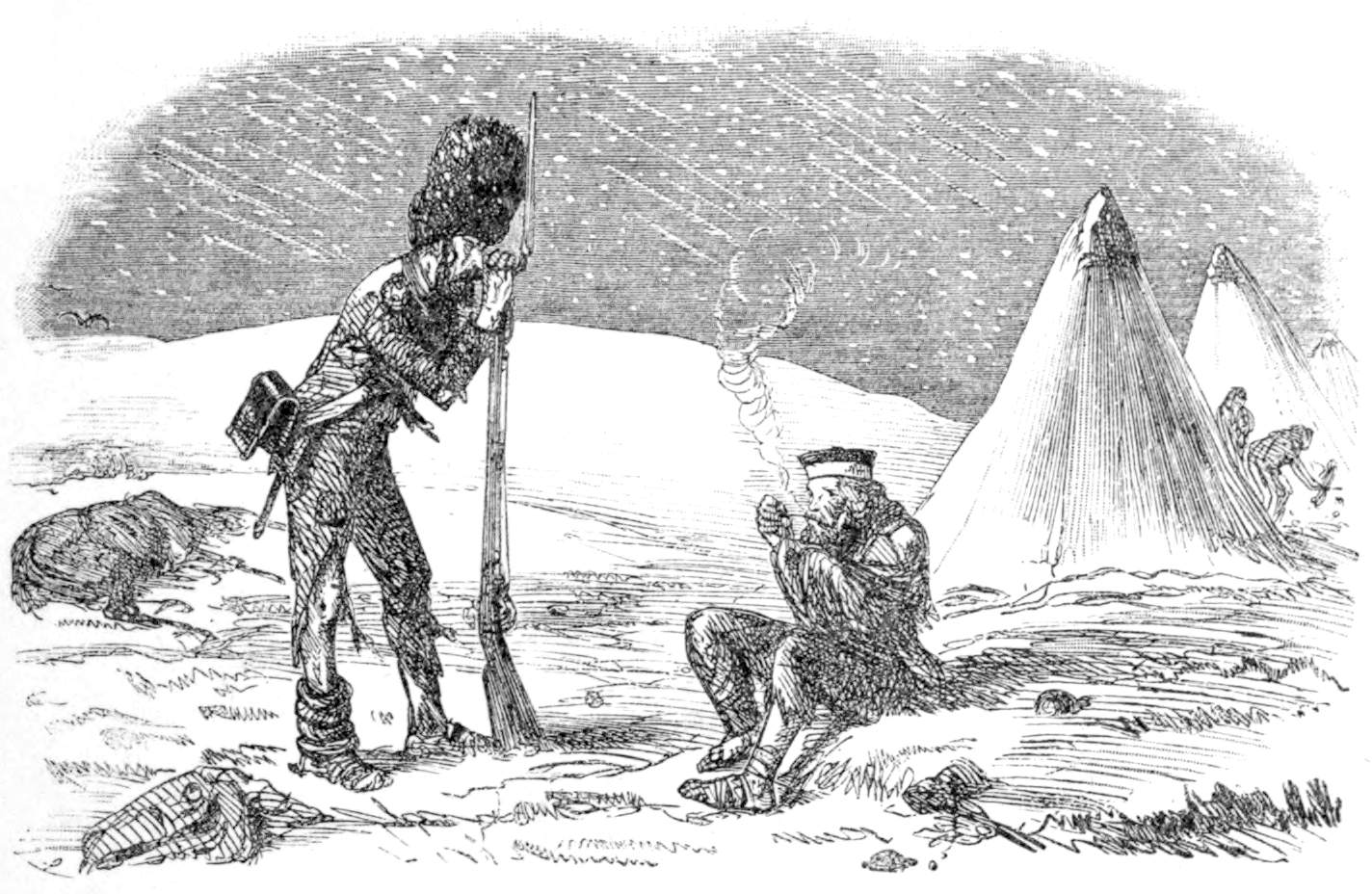

| “How the Guards looked” | From “Punch,” 1855 | 257 |

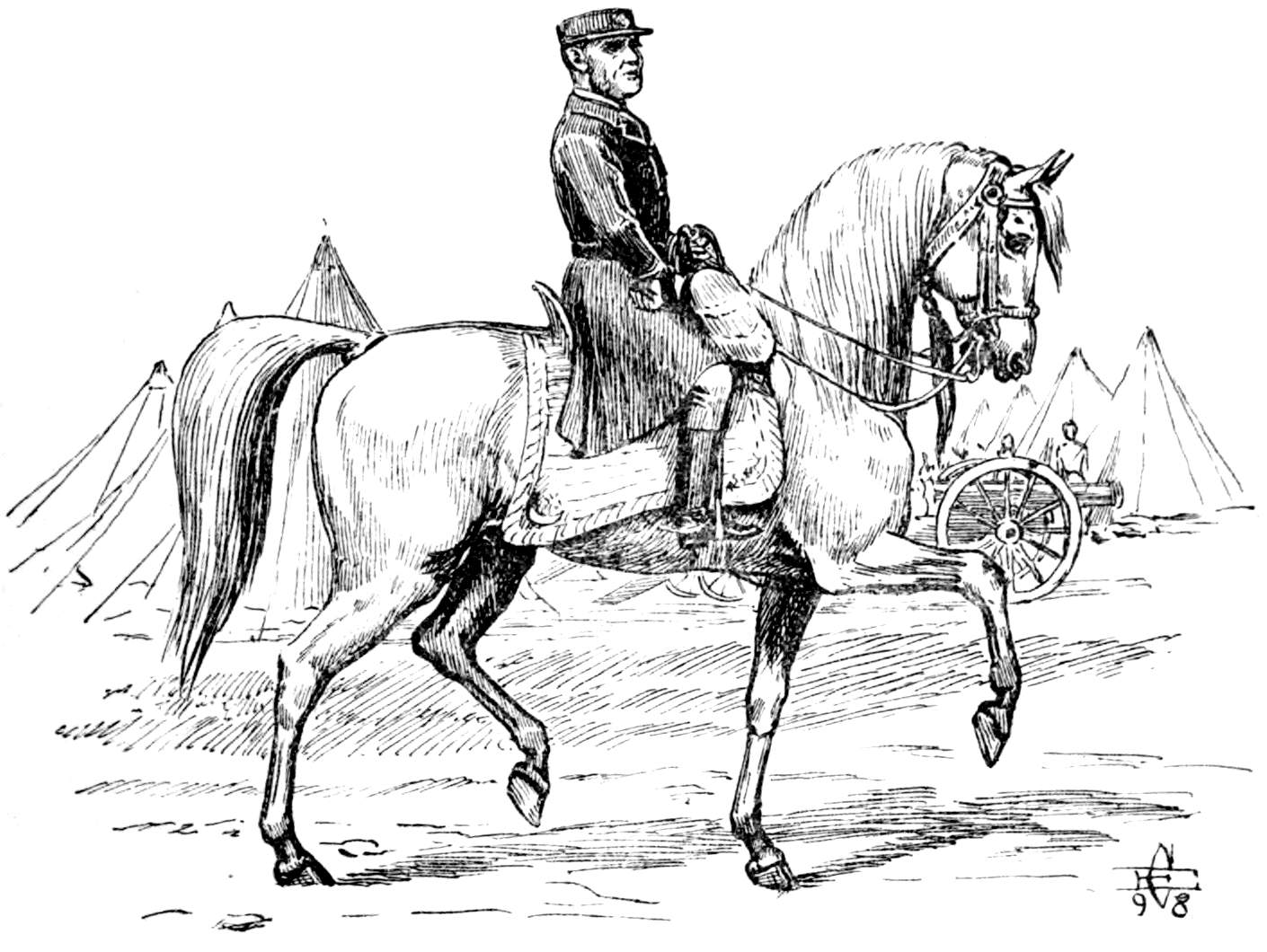

| Omar Pasha’s Arab | E. Caldwell | 261 |

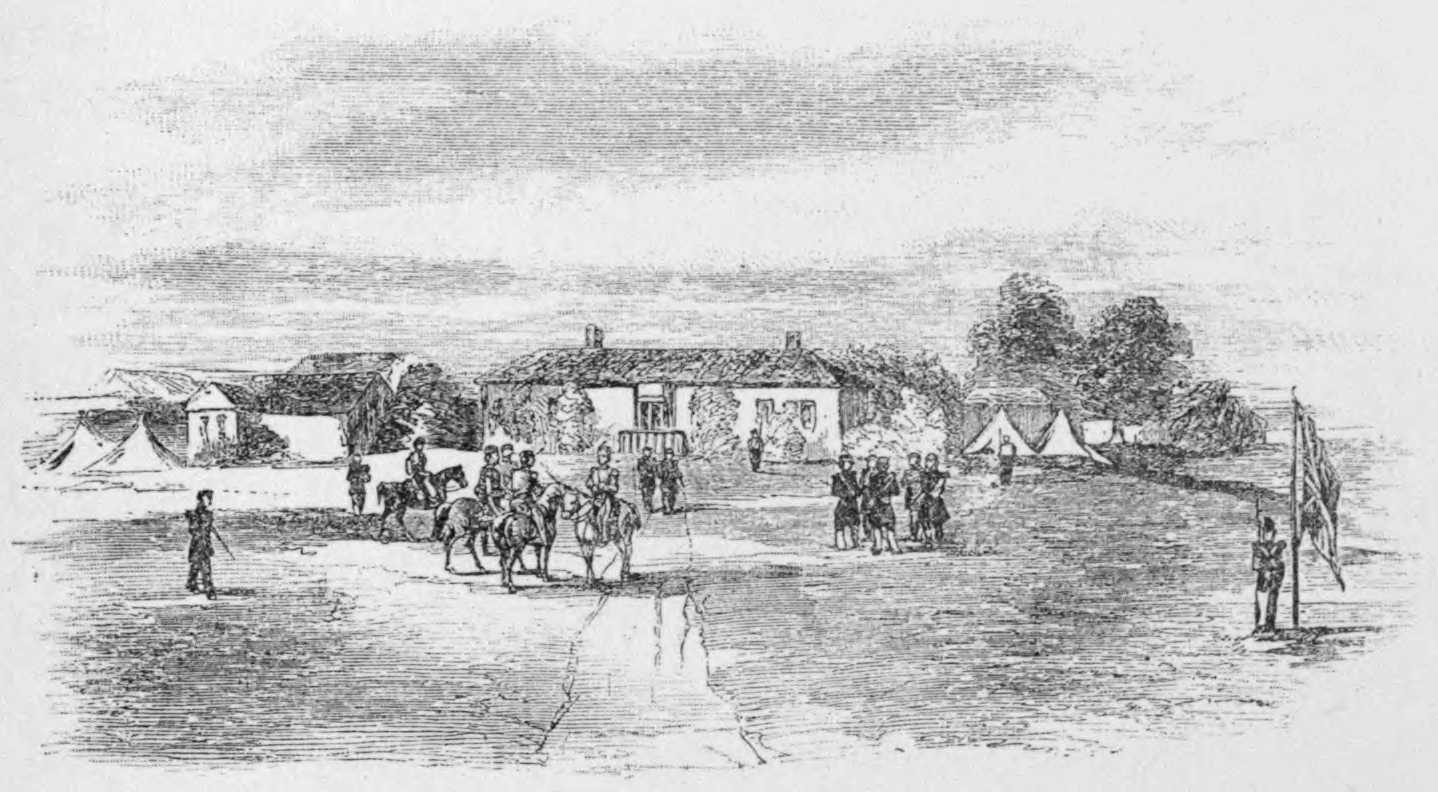

| Headquarters | Simpson, I.L.N. | 265 |

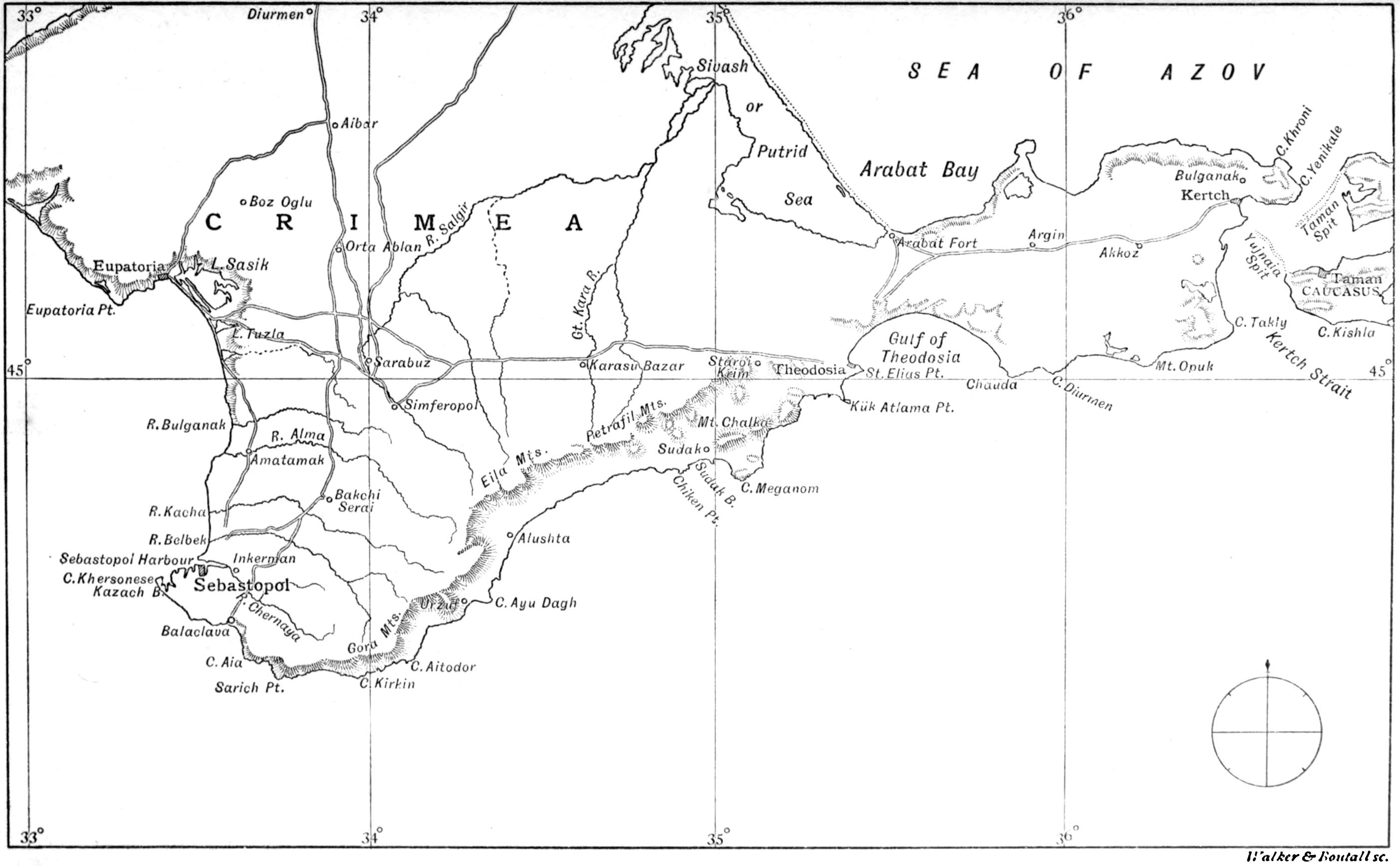

| Map of Crimea | 269 | |

| “Jack, to Newly-Arrived Subaltern ...” | Col. Hon. Sir W. Colville, K.C.V.O., C.B. | 278 |

| In Rear of the Lancaster Battery | ” ” | 281 |

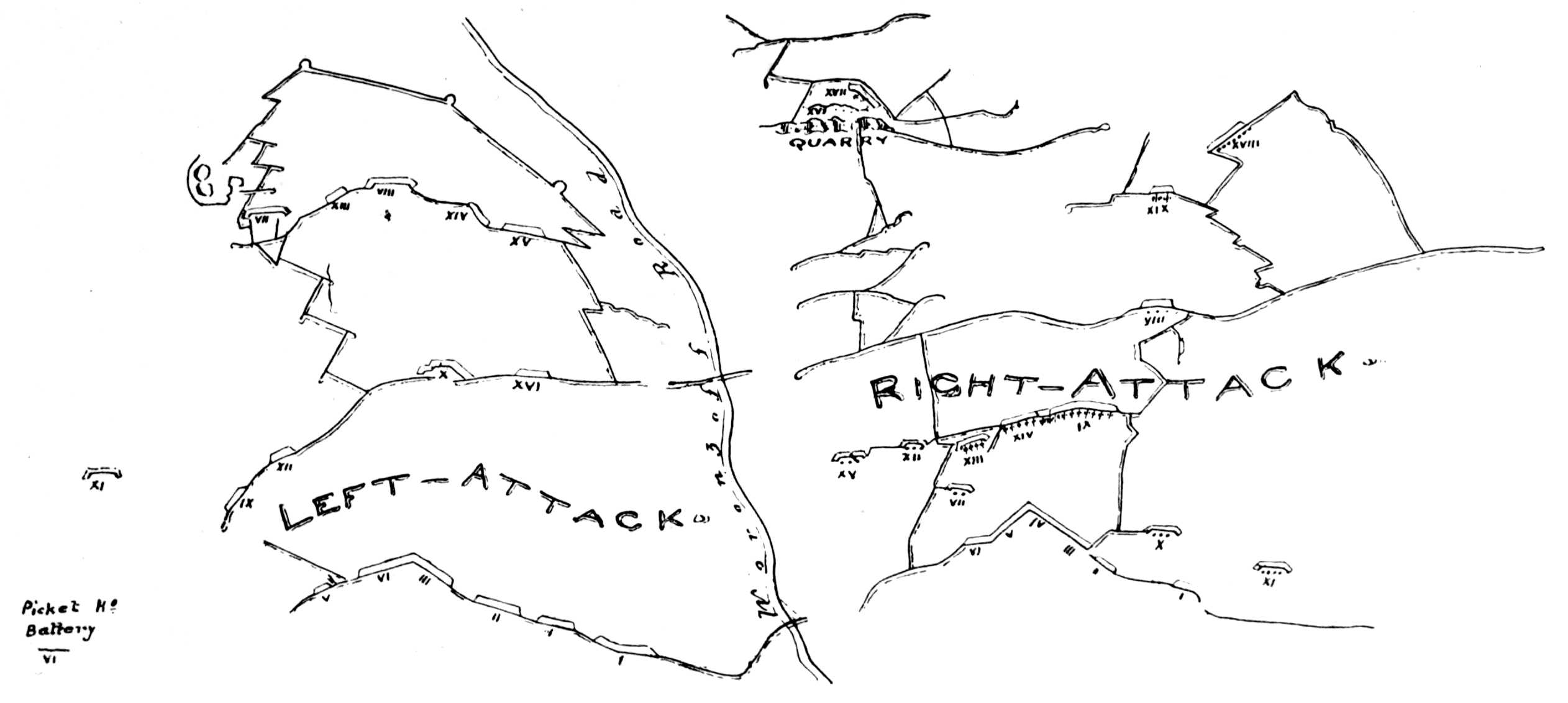

| Plan of Sevastopol | 293 | |

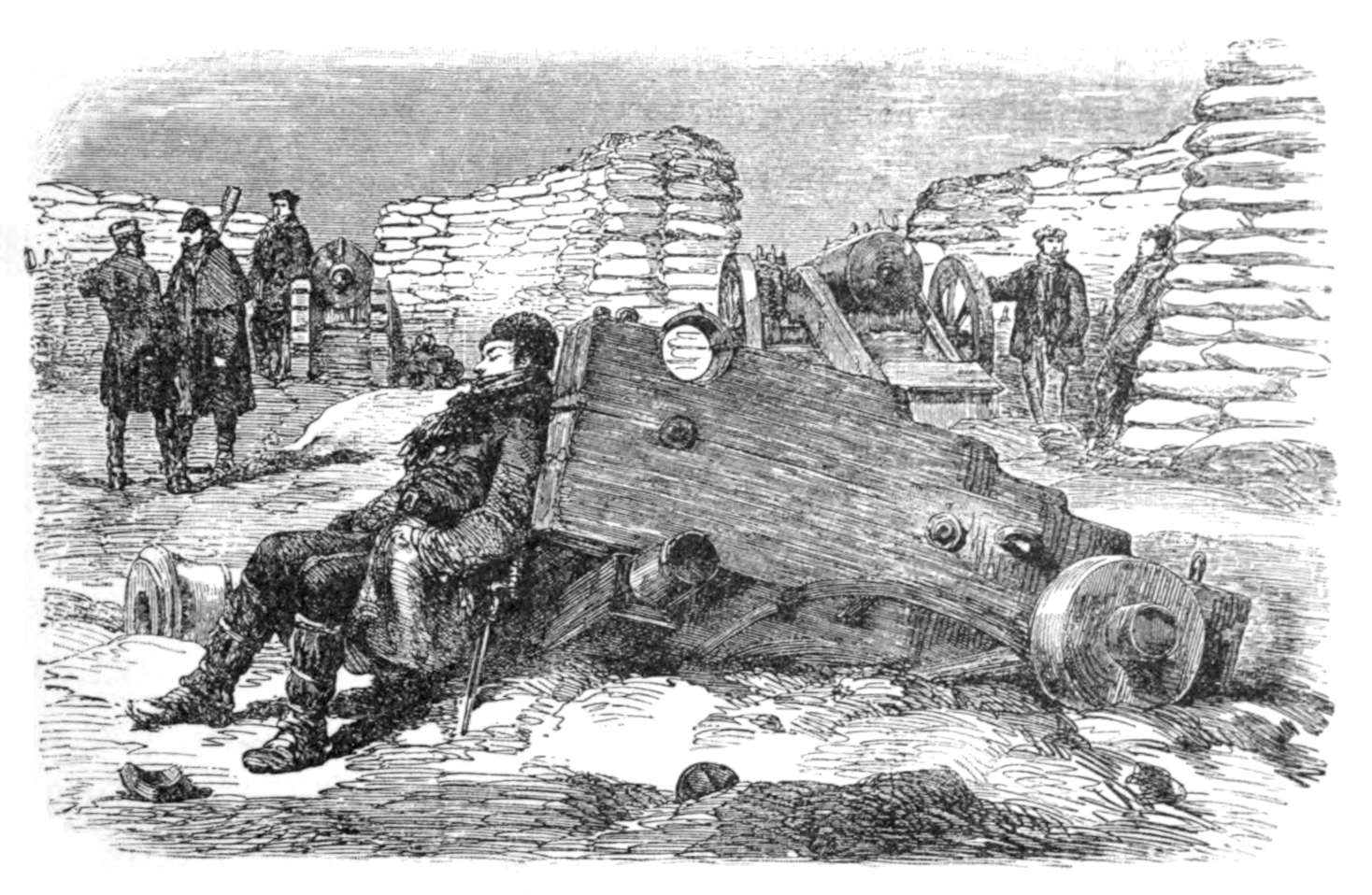

| Inside the Naval Brigade Battery | Simpson, I.L.N. | 295 |

| “Redan” Windham | Nina Daly | 301 |

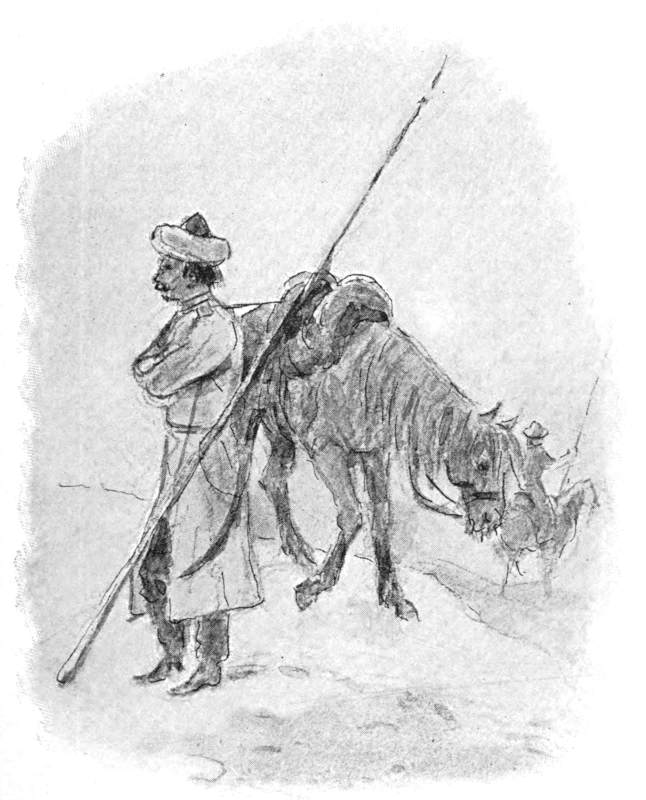

| A Vidette of Cossacks | Col. Hon. Sir W. Colville, K.C.V.O., C.B. | 307 |

[1]

Dido

This being the morning fixed for the departure of our small expedition against the Sekarrans, the Phlegethon weighed at eight and proceeded down the river to await the collection of force.

Among those who accompanied us was the Pangeran Budrudeen, the intelligent brother of the Rajah already noticed. This was an unusual event in the Royal Family, and the departure from the Rajah’s wharf was imposing. The barge of state was decked with banners and canopies. All the chiefs attended, with the Arab priest Mudlana at their head, and the barge pushed off amid the firing of cannon and a general shout to invoke the blessing of Mahomet.

Having seen the last boat off, Brooke and I took our departure in the gig, when another salute was fired from the wharf. Three hours brought us to the steamer. Here we heard that a small boat from the pirate country had, under pretence of trading, been spying into our force, but decamped on our appearance. We now got fairly away, the smaller boats keeping near the shoals in-shore, while the steamer was obliged to make an offing some miles from the coast. From the masthead we distinctly [2] made out the small boat that had left the mouth of the river before, pulling and sailing in the direction of Batang Lupar, up which the Sekarran country lies; and it being desirable that they should not get information of our approach, at dusk, being well in advance, our auxiliary force following, we despatched Brooke’s sampan and one of Dido’s cutters in chase.

With the flood-tide arrived the well-appointed little fleet, and with it the cutter and sampan with two out of the three men belonging to the boat of which they had been in chase, the third having been speared by Seboo on showing a strong inclination to run amuck in his own boat. From these men we learned that Seriff Sahib was fully prepared for defence—his harem had been removed—and that he would fight to the last.

We anchored in the afternoon at the mouth of the Linga, and sent a messenger to caution the chief, Seriff Jaffer, against giving any countenance to either Seriff. The Batang Lupar, thus far, is a magnificent river, from three to four miles wide, and in most parts from 5 to 7 fathoms deep.

Weighed at daylight. Shortly after eleven, with a tide sweeping us up, we came in sight of the fortifications of Patusen. There were five forts. Getting suddenly into 6 feet of water, we anchored. We were well within musket range, but not so formidable a berth as we might have taken up had we been aware of the increasing depth of water nearer the shore; but we approached so rapidly there was no time to ascertain.

The Dido and Phlegethon’s boats were not long in forming alongside. They consisted of the following:—

[3]

In all, 13 officers; 108 seamen; 16 marines.

We had no steam, and to direct a fleet of boats how to attack a succession of half a dozen forts was beyond me. They were off, and they were there! From the Phlegethon we had no difficulty in setting fire to the thatched roofs of the forts. Reinforcements came across the extensive shelter of Patusen Harbour. These we might easily have sunk with Phlegethon’s guns, but there was excitement for them on landing! They never once checked in their advance, but the moment they touched the shore the crews rushed up, entering the forts at the embrasures, while the pirates fled at the rear. In this sharp and short affair we had but one man killed, poor John Ellis, a fine young man, and captain of the maintop in the Dido. He was cut in two by a round-shot while in the act of ramming home a cartridge in the bow-gun of the Jolly Bachelor, of which Lieutenant [4] Edward Turnour was in command. This, and two others badly wounded, were the only casualties on our side.

Our native allies were not long in following our men on shore. The killed and wounded on the part of the pirates must have been considerable. Our native followers got many heads. There were no less than sixty-four brass guns of different sizes, besides many iron, found in and about the forts. The town was extensive, and after being well looted made a glorious blaze. Our Sarawak followers, both Malays and Dyaks, behaved with gallantry, and with our lads dashed in under the fire of the forts. In fact, like their country, anything might be made of them under a good Government.

After our men had dined, and had a short rest during the heat of the day, we landed our force in two divisions to attack a town situated about two miles up, on the left bank of a small river called the Grahan, the entrance to which had been guarded by the forts, and immediately after their capture the tide had fallen too low for our boats to get up. Facing the stream, too, was a long stockade, so that we determined on attacking the place in the rear, which, had the pirates waited to receive them, would have caused an interesting skirmish. Brooke was away independently in the gig. They, however, decamped, leaving everything behind them.

In this town we found Seriff Sahib’s residence, and among other things his curious and extensive wardrobe. It was ridiculous to see our Dyaks dressed out in all the finery and plunder of this noted pirate, whose very name a few days ago would have made them tremble.

We likewise found a magazine in the rear of [5] Sahib’s house, containing about 2 tons of gunpowder, which I ordered to be thrown into the river.

It was evident we attacked Patusen at the right moment: the preparations for its defence were nearly completed, and a delay of a week would have resulted in considerable loss of life. It was the key to this extensive river, the resort of the worst of pirates, and each chief had contributed his share of guns and ammunition towards its defence.

We returned to our boats and evening meal rather fatigued, but much pleased with our work, after ascending near seventy miles from the mouth of the river. The habitations of 5000 pirates had been burnt to the ground, five strong forts destroyed, together with several hundred boats, upwards of sixty brass guns captured, and about a fourth of that number of iron ones spiked and thrown into the river, besides vast quantities of other arms and ammunition, and the powerful Sahib, the great pirate patron for the last twenty years, ruined past recovery, and driven to hide his diminished head in the jungle.

The 8th and 9th were spent in burning and destroying the remains of the staggering town and a variety of smaller boats.

As soon as the tide had risen sufficiently to take us over the shoals, we weighed in the steamer for the country of the Sekarran Dyaks, having sent the boats on before with the first of the flood.

About fifteen miles above Patusen is the branch of the river called the Undop. Up this river I sent Lieutenant Turnour, with Mr. Comber, in the Jolly Bachelor and a division of our native boats, while we proceeded to where the river again branches off to the right and left, as on the tongue of land so formed [6] we understood we should find a strong fort; besides, it was the highest point to which we could attempt to take the steamer. We found the place deserted and houses empty.

We now divided the force into three divisions—the one already mentioned, under Lieutenant Turnour, up the Undop; another, under Mr. D’Aeth, up the Lupar; while Lieutenant Wade, accompanied by Brooke, ascended the Sekarran. I had not calculated on the disturbed and excited state in which I found the country: two wounded men having been sent back from the Undop branch, brought accounts of pirates, chiefly Malays, collected in great numbers both before and in the rear of our small force.

An attempt had been made to cut off the bearer of this information, Nakodah Bahar, who had had a narrow escape, and had no idea of being the bearer of an answer unless attended by a European force. I had some difficulty in mustering another crew from the steamer, and left my friend Captain Scott with only the idlers, rather critically situated. I deemed it advisable to re-collect our whole force, and before proceeding to the punishment of the Sekarrans to destroy the power and influence of Seriff Muller, whose town was situated about twenty miles up, said to contain a population of 1500 Malays, without reckoning the Dyak tribes.

Having despatched boats with directions to Lieutenant Wade and Mr. D’Aeth to join us in the Undop, a tributary of the Batang Lupar, proceeded to the scene of action; leaving the Phlegethon to maintain as strict a blockade of the Sekarran and Lupar branches as, with her reduced force, she was capable of.

[7]

On my joining Lieutenant Turnour, I found him just returned from a very spirited attack which he had made, assisted by Mr. Comber, on a stockade situated on the summit of a steep hill, Mr. Allen, the Master, being still absent on a similar service on the opposite side of the river.

The gallant old chief Patingi Ali was likewise absent in pursuit of the enemy that had been driven from the stockades, with whom he had had a hand-to-hand fight, the whole of which, being on the rising ground, was witnessed by our boats’ crews, who could not resist hailing his return from his gallant achievement with three hearty cheers.

We had now to unite in cutting our way through a barrier across the river similar to that described in the attack on the Sarebas, which having passed we brought up for the night close to a still more serious obstacle in a number of huge trees felled, the branches of which, meeting midway in the river, formed apparently an insurmountable obstacle. But “patience and perseverance” overcame all obstacles. By night only three of the trees remained to be cleared away. On the right bank, about 50 yards in advance of the barrier, stood a farm building, which we considered it prudent to occupy for the night.

Having collected fifty volunteers (Brooke and Wade had then not rejoined), I took Brooke’s schoolfellow Steward, Williamson, and with me Comber, a corporal and four marines, my gig’s crew, and, of course, my trusty John Eager, the sound of whose bugle meant mischief. The remainder composed of a medley of picked Malays and Dyaks.

The house being 100 yards in advance of our party, and 80 from the river, it was difficult of [8] approach, especially at night. The ground swampy, with logs of trees, over which I stumbled, and was up to my arms in mud and water. Nevertheless, there was no noise. It was a roomy building. In one corner I found an enclosure, forming a square of about 8 feet; of this I took possession, and while in the place—it was pitch dark—I quietly divested me of my wet trousers.

“Tiga” (three) was the watchword, in case of a stranger finding his way in. I was contemplating whether my duck trousers were sufficiently dry for me to get into, when every one was disturbed by a most diabolical war-yell. In a moment every man was on his legs—swords, spears, and krisses dimly glittered over our heads. It is impossible to describe the excitement and confusion of the succeeding ten minutes; one and all believed we had been surrounded by the enemy and cut off from our main party.

I had already thrust the muzzle of my pistol close to the heads of several natives, whom in the confusion I had mistaken for Sekarrans; and as each in his turn called out “Tiga!” I withdrew my weapon to apply it to somebody else, until at last we found we were all “Tigas.” I had prevented Eager more than once from sounding the alarm, which from the first he had not ceased to press for permission to do.

The Dyak yell had, however, succeeded in throwing the whole force afloat into a similar confusion, who, not hearing the signal, concluded they, and not we, were the party attacked. The real cause we afterwards ascertained to have arisen from the alarm of a Dyak, who dreamt, or imagined, he felt a spear thrust upwards through the bamboo flooring of our [9] building, and immediately gave his diabolical yell. The confusion was ten times as much as it would have been had the enemy really been there. So ended the adventures of the night in the wild jungle of Borneo.

[10]

Dido: Second Expedition

At daylight we were joined by Wade and Brooke, their division making a very acceptable increase to our force, and by eight o’clock the last barrier was cut through between us and Seriff Muller’s devoted town.

With the exception of his own house, from which some eight or nine Malays were endeavouring to remove his effects, the whole place was deserted. They made no fight, and an hour afterwards the town had been plundered and burnt.

The only lives lost were a few unfortunates, who happened to come within range of our musketry in their exertions to save some of their master’s property.

A handsome large boat belonging to Seriff Muller was the only thing saved, and this I presented to Budrudeen.

After a short delay in catching our usual supply of goats and poultry, with which the place abounded, we proceeded up the river in chase of the chief and his people, our progress much impeded by the immense trees felled across the river.

We ascertained that the pirates had retreated to a Dyak village, situated on the summit of a hill, some [11] twenty-five miles higher up the Undop, five or six miles only of which we had succeeded in ascending, as a most dreary and rainy night closed in, during which we were joined by D’Aeth and his division from the Lupar River.

The following morning, at daybreak, we again commenced our toilsome work. We should have succeeded better with lighter boats, and I should have despaired of the heavier boats getting up had they not been assisted by an opportune and sudden rise of the tide, to the extent of 12 or 14 feet, though with this we had to contend against a considerably increased strength of current.

It was on this day that my ever active and zealous First Lieutenant, Charles Wade, jealous of the advanced position of our light boats, obtained a place in my gig.

That evening the Phlegethon’s first and second cutters, the Dido’s two cutters, and their gigs, were fortunate enough to pass a barrier composed of trees recently felled, from which we concluded ourselves to be so near the enemy that, by pushing forward as long as we could see, we might prevent further impediments from being thrown in our way. This we did, but at 9 P.M., arriving at a broad expanse of the river, and being utterly unable to trace our course, we anchored our advance force for the night.

The first landing-place we had no trouble in discovering, from the number of deserted boats collected near it. Leaving these to be looted, we proceeded in search of the second, which we understood was situated more immediately under the village, and which, having advanced without our guides, we had much difficulty in finding. The circuit of the base of the hill was above five miles.

[12]

During this warfare, Patingi Ali, who, with his usual zeal, had here come up, bringing a considerable native force of both Malays and Dyaks, was particularly on the alert; while we in the gig attacked Seriff Muller himself.

Patingi nearly succeeded in capturing that chief in person. He had escaped from his prahu into a fast-pulling sampan, in which he was chased by old Ali, and afterwards only saved his life by throwing himself into the water and swimming to the jungle; indeed, it was with no small pride that the gallant old chief appropriated the boat to his own use.

In the prahu were captured two large brass guns, two smaller ones, a variety of arms, ammunition, and personal property, amongst which were also two pairs of handsome Wedgewood jars.

While my crew were employed cooking, I crept into the jungle and suddenly fancied I heard the suppressed hum of many voices not far distant. I returned to our cooking party and bade Wade take up his double-barrel and come with me. I had not penetrated many yards before I came in sight of a mass of boats concealed in a snug little inlet, the entrance to which had escaped our notice. These boats were filled with piratical Dyaks and Malays, and sentinels posted at various points on the shore.

My first impulse was to conceal ourselves until the arrival of our force, but my rash though gallant friend deemed otherwise, and, without noticing the caution of my upheld hand, dashed in advance, discharging his gun, calling upon our men to follow.

It is impossible to conceive the consternation and confusion this our sudden sally occasioned among the pirates. The confused noise and scrambling from [13] their boats I can only liken to that of a suddenly-roused flock of wild-ducks.

Our attack from the point whence it came was evidently unexpected; and it is my opinion that they calculated on our attacking the hill, if we did so at all, from the nearest landing-place, without pulling round the other five miles, as the whole attention of their scouts appeared to be directed towards that quarter.

A short distance above them was a small encampment, probably erected for the convenience of their chiefs, as in it we found writing materials, two or three desks of English manufacture, on the brass plate of one of which, I afterwards noticed, was engraved the name of “Willson.”

To return to the pirates: with our force, such as it was—nine in number—we pursued our terrified enemy, headed by Wade.

They foolishly themselves had not the courage to rally in their judiciously selected and naturally protected encampment, but continued their retreat (firing on us from the jungle) towards the Dyak village on the summit of the hill. We collected our force, reloaded our firearms; and Wade, seeing from this spot the arrival at the landing-place of the other boats, again rushed on in pursuit.

Before arriving at the foot of the steep ascent on the summit of which the Dyak village stood, we had to cross a small open space of about 60 yards, exposed to the fire from the village as well as the surrounding jungle. It was before crossing this plain that I again cautioned Wade to await the arrival of his men, of whom he was far in advance.

We suddenly came on to the snuggest and best-sheltered boat harbour I ever saw. The land was [14] high towards the river, with a narrow and well-concealed entrance opening to the river, so high that an impromptu bridge in the shape of a large tree had been thrown across. It was along this that Wade was proceeding in advance, calling “Come on, my boys!” And I am afraid I did not disguise my gratification at seeing him disappear into the branches of a large tree growing beneath.

By this time the cutter and other boats had landed at our point and were coming up. I had scarcely got across the tree-bridge, when I saw my friend scrambling up the opposite side, himself unhurt, his gun not discharged.

Our men were now landing fast, and it was for very shame I could not allow Wade to proceed alone. Only a few minutes afterwards, while still trying to check him, a bullet from the hill took his thumb and twisted him in my direction; while a second shot struck him in the ribs and lodged in the spine—and he fell.

By this time a strong party were up, whom I directed to pass on, while I ascertained that poor Wade’s heart had ceased to beat.

We laid the body in a canoe, with the Union Jack for a pall, and descended the river. In the evening, the force assembled, committed the body to the deep. I read that impressive service from a Prayer-Book brought up by poor Wade himself—as he put it, “in case of accident.”

Before we again got under way, several Malay families, no longer in dread of their piratical chief, Seriff Muller, gave themselves up to us as prisoners—the first instance of any of them having done so. We found sundry suspicious documents, exposing deep intrigues and conspiracies, and brought up for the [15] night off the still burning ruins of Seriff Muller’s town.

On Tuesday we again reached the steamer. We still had something to settle with the Sekarrans, and, having rested for two days, started on the 17th on our last expedition.

The weather was unusually fine, and we squatted down to our curry and rice with better appetites.

Our approach was made known by fires; but we once dropped, without their being aware of our approach, upon a boatful of Dyaks, dressed for war, with feather cloaks, brass ornaments, and scarlet caps. The discharge of our muskets and the capsizing of the war-boat was the work of an instant, and those who were uninjured escaped into the jungle.

We experienced some difficulty in finding a suitable place for our bivouac. While examining the most eligible-looking spot on the bank of the river, the crew of one of the Phlegethon’s boats, having crept up the opposite bank, came suddenly on a party of Dyaks, who saluted them with a war-yell and a shower of spears. The Phlegethon’s men took to the water, much to our amusement as well as the Dyaks.

The place we selected for the night was a large house, about 40 yards from the edge of the river. Here we united our different messes and passed a jovial evening. The night, however, set in with a fearful thunderstorm. The rain continued to fall in torrents, but cleared up at daylight, when we proceeded.

As yet the banks of the river had been a continued garden, with sugar-cane and bananas; the scenery now became wilder.

We were in hopes that this morning we should [16] have reached their capital, Karangan, supposed to be about ten miles further on. Not expecting to meet with any opposition for some miles, we gave permission to Patingi Ali to advance cautiously with his light division, with orders to fall back on the first appearance of any natives. As the stream was running down strong, we held on to the bank, waiting for the arrival of the second cutter, in which were Brooke and Jenkins.

Our pinnace and second gig having passed up, we remained about a quarter of an hour, when the report of a few musket-shots told us that the pirates had been fallen in with. We immediately pushed on, and as we advanced the increased firing from our boats, and the war-yells of some thousand Dyaks, let us know that we had met.

It is difficult to describe the scene as I found it. About twenty boats were jammed together, forming one confused mass—some bottom up; the bows and sterns of others only visible, mixed up, pell-mell, with huge rafts—and amongst which were nearly all our advanced division.

Headless trunks, as well as heads without bodies, were lying about; parties hand to hand spearing and krissing each other, others striving to swim for their lives; and entangled in the common mêlée were our advanced boats, while on both banks thousands of Dyaks were rushing down to join in the slaughter, hurling spears and stones on the boats below.

For a moment I was at a loss what steps to take for rescuing our people from the position in which they were, as the whole mass, through which there was no passage, were floating down the stream, and the addition of fresh boats only increased the confusion.

[17]

Fortunately, at this critical moment one of the rafts, catching the stump of a tree, broke this floating bridge, making a passage, through which my gig (propelled by paddles instead of oars)—the bugler, John Eager, in the bow—was enabled to pass.

It occurred to Brooke and myself simultaneously, that by advancing in the gig we should draw the attention of the pirates towards us, so as to give time for the other boats to clear themselves. This had the desired effect. The whole force on shore turned, as if to secure what they rashly conceived to be their prize.

We now advanced mid-channel, spears and stones assailing us from both banks. Brooke’s gun would not go off, so, giving him the yoke-lines, I, with the coxswain to load, had time to select the leaders from amongst the savage mass, on which I kept up a rapid fire.

Allen, in the second gig, quickly coming up, opened upon them from a Congreve rocket-tube such a destructive fire as caused them to retire behind the temporary barriers where they had concealed themselves previous to the attack on Patingi Ali, and from whence they continued, for some twenty minutes, to hurl their spears and other missiles, among which were short lengths of bamboo loaded with stone at one end. The sumpitan was likewise freely employed, and although several of our men were struck, no fatal results ensued. Mr. Beith, our assistant surgeon, dexterously excised the wounds, and what poison remained was sucked out by comrades of the wounded men.

From this position, however, the Sekarrans retreated as our force increased, and could not again muster courage to rally. Their loss must have been [18] considerable. Ours might have been light had poor old Patingi Ali attended to orders.

He was over confident. Instead of falling back, as particularly directed by me, on the first appearance of any of the enemy he made a dash, followed by his little division of boats, through the narrow pass. The enemy at once launched large rafts of bamboo and cut off his retreat. Six war-prahus bore down, three on either side, on Patingi’s devoted followers. One only of a crew of seventeen escaped to tell the tale.

When last seen by our advanced boats, Mr. Steward and Patingi Ali were in the act (their own boats sinking) of boarding the enemy. They were doubtless overpowered and killed, with twenty-nine others. Our wounded in all amounted to fifty-six.

A few miles further up was the capital of Karangan, which we carried without further opposition.

Having achieved the object of our expedition, we dropped leisurely down the river; slept in our boats, with a strong guard on shore.

On the 20th we reached the steamer, where we remained all the next day attending to the wounded.

On the 22nd we reached Patusen, finding everything in the wretched state we had left it. At 8 P.M. we heard the report of a gun, which was repeated nearer at nine, and before a signal rocket could be fired, we were hailed by the boats of the Samarang, Captain Sir Edward Belcher, and the next moment he was alongside the Phlegethon with the welcome news of having brought our May mail.

It appears that, on arrival of Samarang off Morotoba, Sir Edward heard of the loss we had sustained, and, with his usual zeal and activity, came to our [19] assistance, having brought his boats no less than 120 miles in about thirty hours.

There were two accidents just at this moment which might have been more serious. D’Aeth, hearing of the mail, hurried on board the Samarang in a small sampan, and was capsized. His skill in swimming saved him; his one paddler caught hold of a boat near. No sooner than these had been cared for, when Brooke, whose ears, always on the alert for native cries, heard voices in trouble, and, jumping into his Singapore sampan, pushed off with Siboo to the assistance of our Dyak followers, who had been capsized by the bore. He rescued three out of a crew of eleven, and these were half drowned when he reached them.

We moved down as far as the mouth of the Linga, and on the night of the 24th were once again in Sarawak. Here the rejoicings of the previous year were repeated.

But having received information that Seriff Sahib had taken refuge in the Linga River, and, assisted by Seriff Jaffer, was again collecting followers, we were off again on the 28th, with the addition of the Samarang’s boats. And, determining to crush this persevering pirate, in the middle of the night came to an anchor inside the Linga River.

When our expedition had been watched safely outside the Batang Lupar on its return to Sarawak, all those unfortunate families that had concealed themselves in the jungle after the destruction of Patusen and Undop, emerged from their hiding-places, and by means of rafts, canoes, packerangans, or anything that would float, were in the act of crossing towards Bunting, a flourishing place. Their dismay can well be imagined when at daylight on [20] the morning of the 29th they found themselves carried by the tide close alongside the terror-spreading steamer, in the midst of our augmented fleet. Escape to them was hopeless; nor did the women seem to mind. It was a choice between starvation in the jungle or coming under submission to the white man.

I need not say that, instead of being molested, they were supplied with such provisions and assistance as our means would permit, and allowed to pass quietly on. We sent several of our native followers into the Batang Lupar to inform the fugitives that our business was with the chiefs and instigators of piracy, and not with the ryots of the country.

With the ebb-tide a number of boats came down from the town containing the principal chiefs, with assurances of their pacific intentions; welcoming us with presents of poultry, goats, fruit, etc., which we accepted, but paying for them, either in barter or hard dollars, the fair market price. We learned that Seriff Sahib had arrived at Pontranini, some fifty miles beyond their kampong.

We immediately proceeded in chase of him, at the same time despatching two boats to look out for Macota, who was expected at the mouth of the river. We knew what the fate of this once powerful chief would be if he fell into the hands of our friendlies. He was captured alive in a deep muddy jungle into which he had thrown himself when our men arrived. Leaving Macota a prisoner on board the Phlegethon, with the flood-tide we pushed forward in pursuit of Seriff Sahib.

For two days we dragged our boats twenty miles up a small jungly creek; but Seriff Sahib fled across the mountains in the direction of the Pontiana River. [21] So close were we on his rear that he threw away his sword, and left behind him a child, whom he had hitherto carried, in the jungle. Thus this notorious chief was driven, single and unattended, out of the reach of doing any further mischief.

The boats returned, and took up a formidable position off Bunting, where Seriff Jaffer was summoned to a conference, which he attended, but under compulsion from his people, who feared their kampong being destroyed.

On this occasion I had the satisfaction of witnessing a splendid piece of oratory delivered by Brooke in Malay. The purport of it was, as I understood, to point out the horrors of piracy on the one hand, which the British Government determined to suppress, and on the other the blessings arising from peace and trade, which it was equally our wish to cultivate; and he concluded by fully explaining that the measures adopted by us against piracy were for the protection of the peaceful communities along the coast. The people listened with great attention; a pin could have been heard, had it dropped, during Brooke’s fine speech.

The force again reached Sarawak, and thus terminated a successful expedition against the worst class of pirates on the coast of Borneo.

[22]

Dido

Steamer’s crew cutting wood, I writing distressing letters to the friends of Wade, as well as to the father of Dr. Simpson. Hospitably entertained by Belcher.

Landed sundry parties after deer and hog. Oysters fine, the best things here.

At an early hour started on a pleasure excursion. Late at night anchored in the Lundu River, having tiffed by the way at one of the small islands on splendid oysters.

Anchored off the town; visited, and was hospitably entertained by, the Dyaks. In the evening had a feast and a war-dance; was in other ways much amused. Slept in the Dyak “scullery” house.

Collected all the dogs and beaters and proceeded to the mouth of the river. All sport confined to the Dyaks, we never getting a shot; very good fun, though—a hog was caught by dogs and speared by natives.

Landed again early; more hogs taken by the natives. Working on towards Santobong; capital luncheon on the finest oysters. Dined on board the Samarang.

Brooke and self returned to Dido in gig, twenty-five [23] miles’ pull. Found heavy sick-list, one marine just expired of dysentery.

Took up quarters with Brooke at The Grove. Deputations and tenders of allegiance from all the surrounding chiefs satisfactory.

Preparing for moving down. Boats to finish; spars to get on board; captured guns to embark. Visited the Rajah and the Datu, “Father of Hopeful,” his women sprinkling us with yellow rice and gold-dust—one graceful and pretty and well dressed.

Too much to do on board. Did not go off to muster.

At daylight saw from my window Dido salute Rajah and commence dropping down the river.

Went down after breakfast, accompanied by Brooke, and found my Dido at anchor off the junction. Moved further down on rising of tide.

Williamson, Turnour, Partridge, Charlie Johnson, and Douglas came down from Sarawak to dinner.

Cruikshank and Williamson to dinner. Finished my claret.

Reached the mouth of the river. Present of warlike weapons from Budrudeen. Took leave of dear Rajah Brooke, and worked the ship over the bar of the Maratabu.

Arrived in Singapore. Ordered home. More anxious for passage than my one cabin can hold. Selected a rough diamond, but great character, one Michael Quin, lately Captain of Minden, hospital ship, also Lieutenant Inglefield. I had but one cabin, but could swing more than two cots.

Pleasure of thoughts of home damped by news of the death of my sister, Lady Leicester.

News of Pelican having sprung a leak; hope not. Phlegethon off for Brooke and Borneo. Dined with [24] Oxley. His nutmeg plantation worth seeing—cinnamon and cloves.

Lots of rain. Napier spliced this morning. Tiffin at Balestiers’ to meet the happy pair. Good fellow Napier, and a pair well matched.

Up very early. On board Diana steamer with Governor and Mrs. Butterworth. Lady party; Dido’s band. Returned by Rhio Straits. Dance on board. Pleasant day.

Called on the Blundells. Like her and her sister much. Dined with Stevenson.

A snug little dinner of ten good fellows prior to a dance given by Tom Church in honour of the Dido’s Captain. Band got drunk.

My Dido visited by Governor and Mrs. Butterworth, Mrs. Blundell, and sister—the three nicest women in Singapore. A grand parting dinner given to me by the inhabitants of Singapore. Nervous, very, making my speech.

Old Balestier, American Consul, on board; salutes, etc., Governor, giving a grand dinner to “meet Captain Keppel”; ladies there; more nervous in returning thanks.

Weighed from Singapore. Fort saluting me. Invalids improving.

Passed mouth of the Moowar, of bygone memories. Came to off Malacca at sunset.

Called on Governor; both nice people. Visited Salmona and stopped to dinner; drove in with Morrison afterwards.

Young Barney Rodyk embarked; sadly pressed for room; made sail. Wolverine in co.

Well ahead of Wolverine. Came to off Parcelar Hill; boarded by a boat from a ship full of pilgrims from Mecca, having struck on a bank with [25] loss of rudder and hard up for water. Sent Wolverine to her assistance.

No use fretting about the wind. Hardly consider myself as homeward bound until round Acheen Head.

Decided, against Master, on southern passage, and anchored off Penang at sunset. Went to Captain’s house, the most comfortable quarters in India. Issued invitations: “Captain Keppel and officers request the pleasure of everybody’s company to-morrow evening.” Dined with Sir William and Lady Norris. Mrs. Hall at home.

Visited various hospitals with Cantor—one of lunatics of all sorts. Got “Chopsticks” from school. Dined with old Lewis. Capital ball and supper given by “Didos.” Kept up till daylight did appear.

Weighed before turning in; very seedy, though. Fort saluted me with 13 guns. Really off for home.

Lots of talk about the ball; everybody pleased.

One of the invalids from Driver died—a young man; the effects of Hong Kong climate. Committed his remains to the deep. Sensible to the last that he was going, but did not seem to trouble himself as to the road; a good man, too, in his way.

Anniversary of the birthday of Princess Royal. Run of 251 miles in last twenty-four hours.

My cabin-meeting of the fine arts. Inglefield doing me pictures of my Dido. Ran into Simon’s Bay with a leading wind, saluting the flag of my kind friend Sir Jos. Percy, of Mediterranean memory, whose flag was now flying on board Winchester—Captain Charles Eden. Found George Woodhouse here in the Thunderbolt, 6, a steam vessel. In fact, I felt myself already at home—scarcely a stone on shore that did not convey some pleasant [26] reminiscence of happy days. In every house a home. While refitting I had scarcely time to call on half my kind friends. Among those I undertook to entertain at my table, in addition to my two passengers, was Edward Drummond, a nephew of the Admiral, and about to enter the Church. [Years afterwards I was his guest at Cadland, Southampton, and he the head of the great Drummond Bank at Charing Cross.] My other guest, a quiet, retiring Swede, who had served his term in our service, by name Adleborg, a clever artist as well as a good fellow.

Luncheon with Lady Sarah Maitland—like the Lennoxes, nice family. At Wynberg; a very agreeable dinner and evening. Kerr Hamilton there.

Ship ready. Stopped to luncheon with Admiral at one. Went over Winchester: nice order and beautifully clean. My Dido under way, Charles Eden putting me on board. Outside, a freshening breeze from the south-east, but we had to weather the Cape. Topgallant sails over double-reefed topsails; a strong set against us. It was not until close to the Anvil and Bellows that we felt the full strength of the current. The Master and self had taken our position on the forecastle, each holding on to the up-and-down part of the fore-topsail sheets, spray breaking over us. We now became aware of what we had undertaken. On looking under the foot of the fore-sail, the Cape and South Africa appeared to be rushing at us: it was too late either to bear up or attempt to tack. Held on, I am afraid, with eyes closed. The Master was the first to call out, “Wave weathered”; the offset from the rocky Cape alone saved us: we appeared to be rushing up the west side of the African coast. On the [27] weather-quarter the Cape appeared close to, but towering far above our mast-heads. By degrees, but slowly, we drew off the west coast. I do not believe that any other ship could, under the circumstances, have been saved.

Adleborg a first-rate artist, clever at allegorical sketches of Dido, which I value; very clever and witty they are.

2 A.M.—Anchored at St. Helena. Visited old Solomon and his shop; also Colonel and Mrs. Trelawney. Weighed at 1.30 P.M. According to notice, made sail 3 P.M. Found Larne and Rapid.

Sails splitting and ropes giving way; foolish economy, ships not being better supplied.

Breeze freshening up; thermometer falling; bitter cold, hazy weather. Hauled in; made the land to the eastward of Bill of Portland; bore up for the Needles: arrived at Spithead. Reported myself to my old friend Hyde Parker, Admiral Superintendent of the Dockyard, Commander-in-Chief Sir Charles Rowley being on leave. It was blowing fresh from the S.E., but having an experienced pilot, gave the Master leave to stay on shore the night, and sent my gig on board.

Admiral Parker said I had better call in the afternoon, as he had telegraphed to the Admiralty. I then visited my old friend Casher, the wine merchant, and inquired if he knew anything of the whereabouts of my wife, as he had always forwarded parcels between us. He informed me that she had come home from Boulogne: only two days ago he had sent parcels to my place at Droxford, where she had joined her father, who, with his family, had taken possession.

The days were short, and it was dark before I got [28] back to the Admiral; he informed me that Dido was ordered to Sheerness. I ventured to state that I had ordered my gig on board. He said: “I have anticipated that; you will find the Fanny tender fast to a buoy at the harbour, with orders to take you off.”

Now this was a go; I had been more than four years absent: my wife within thirteen miles.

I went to Casher’s and inquired if he had a man acquainted with Gosport, or any one who could find a Mr. Allen, Master of the Dido, and bring him to me. I waited a good while, in cocked hat, sword, and epaulettes, before the poor Master appeared in pea-jacket and oilskin, etc. I soon explained the state of affairs.

He was just about my size. It ended by my saying that he must change clothes with me. The Fanny was waiting at the buoy. He would personate me, find orders on board, and obey them. Allen muttered something about losing my commission. We went off in a wherry. On his getting on board he received his orders, opened and read them. I touched my hat, and said “Goodbye, Sir,” and told the waterman to land me at Gosport. Reached Droxford in time for dinner! Brother-in-law soon rigged me in proper costume.

Following morning took wife and self off in a yellow post-chaise, but my danger of being found out was not over. The Captain Superintendent, W. H. Shireff, was an old friend of mine; fond of driving a team of horses, and we used to think he managed it in a seamanlike way.

When we arrived at the dockyard gates it was luckily quite dark. Drove to the Superintendent’s house and took him at once into my confidence.

[29]

No news of Dido! Shireff gave us a steamer to Sheerness. Took a fly to the pilot, where we had lodged while fitting out.

It was the third night before Dido arrived, when, in the early morning, the good pilot Taylor took me off and I returned the Master his hat and pea-jacket. Soon after 8 A.M. reported arrival of Dido to Vice-Admiral Sir John Chambers, K.C.B.

My Dido inspected for last time by Admiral Sir John White. Very cold and rainy weather. Men showed themselves well to the last. My brother Tom came down.

Getting on with the dismantling. Went on board with Tom and wife. Bitter cold weather. Tom stopping with us—affectionate, good fellow.

Preparations for paying progressing. Dirty and bitter cold weather continuing. Custom House people troublesome. Smuggling progressing. Paying off days much alike!

My reign in Dido finished this morning. Paid off, men receiving about £4000. Glad as I am to get back, I do not leave my ship without feelings of regret.

[30]

England

Dido paid off. Arrived with wife in London to enjoy half-pay! My father living in Berkeley Square, we knew where to find a dinner.

Summoned to Admiralty. Gracious reception by Lord Haddington.

News from Brooke. Labuan ceded to the British Government. Brooke had entrusted me with his private diary, and a carte-blanche to use my discretion about publishing—a more responsible charge than I was then aware of. I had a friend, Jerdan, editor of the Court Journal. After consultations it was decided to publish, under the title of “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido.”

At my brother-in-law, Stephenson’s, in Arlington Street, always had a bed.

To Woolwich to see Commodore Sir Francis Collier, in charge of the dockyard, his broad pennant flying on the William and Mary yacht. Visited also George Goldsmith, now married, living there.

Went to Portsmouth on a visit to my late Chief, Admiral Hyde Parker and his charming family. Remained a week.

Attended levee with Granville Loch. Presented [31] by Sir William Parker on return from China. Her Majesty said something nice to me, which, in my nervousness, I was sorry not to have heard.

My Mids, D’Aeth and Jenkins, passed first and second out of the lot at Portsmouth. My father gave me the copy of a correspondence between Lord Haddington and himself about my being the only Captain not recommended for the C.B. Lord Haddington wrote: “Captain Keppel’s ship had not been under fire in action.” Father stated that Dido was not the only ship. Lord Haddington replied: “It is evident you allude to the Endymion, Captain Grey, whose name had been mentioned to General Sir Hugh Gough by Brigadier-General Schoedde.” Father could not help thinking it was a hard case, which Lord Haddington admitted, and promised that my name should be down for the first vacancy. I mention this here, as the subject was alluded to years afterwards. Sir Grey Skipwith, recollecting my weakness, offered me a mount with the Warwickshire Hounds, and before leaving town I dined with that distinguished soldier, Sir William Keir Grant.

Quickly found my way to Newbold Hall. Sir Grey and his large family charming as ever.

Started from stables, the usual dozen red coats. Meet at Shuckborough, found at Cranborough. Got away with the first flight. Not recollecting the country, found myself with about a score charging the river Leam. Reached opposite bank, which was rotten. Fell back and found the bottom. I believe only two got out safe. My new pink came out black.

Back to London to dine with Sir Thomas Trowbridge.

To Greenwich by rail, to dine in hospital with that [32] grand old Admiral, Sir Robert Stopford, his happy lady and family looking so well.

Templer and I enjoyed an excellent dinner Jerdan gave us at the Garrick Club.

Mr. Edward Ellice kindly lent us his house, 18 Arlington Street. Admiral and Mrs. Sam Rowley dined with us on their way through London, she informing me I was left in his will, heir and executor.

We attended the Queen’s Drawing-Room.

Lunched with the Hawleys, who had established themselves in Halkin Street. He had a charming yacht, the Mischief, with a woman for figurehead, which his wife disapproved of. An image of a monkey was executed to replace the lady; but there was so much trouble and legal expense in changing a figurehead, that the monkey was transferred to a box seat over my coach-house door. As I had no carriage the groom was not jealous.

Archie MacDonald dined with us prior to the Queen’s Ball. On that occasion, although an old Fusilier Guardsman, he hid himself behind a screen till the ceremony was over.

Glad to take possession of our snug little place at Droxford. A four-horse coach running between Gosport and London passed our door twice daily: a great convenience. William Garnier’s place, Rooksbury Park, was within two miles of us.

In London met Sir Henry Pottinger: had a walk and a talk about China times.

Arthur Cunynghame, our China friend, came to stay with us. Also Fred Horton.

Met George Delmé at the station. With niece to see departure of the fleet from Spithead. Too late to get out, so took a cruise in the Freemart Fair.

At Cams. In Delmé’s drag to Goodwood Races. [33] Delmé Radcliffe, Onslow, the two Foleys, etc. My father being of the Goodwood party, wife and I were invited into the Duke’s end of the grand stand. Unaccustomed to racing society, my wife was a trifle nervous. However, observing my father in deep conversation with a light weight in a blue coat with brass buttons, yellow, leathers and mahogany tops, she inquired of Lady Albemarle if that was His Lordship’s jockey. To which this amiable lady replied in a loud voice: “No, my dear. That is the Duke of Bedford.”

In Delmé’s drag. Ten outside!

The great Cup Day. Twenty-one horses started.

Concluded a splendid week’s racing.

We left London for Quidenham. Glad to be where I had passed my youth. The dear old father, no longer able to shoot, had taken to breeding bloodstock. The park near the river was cut into paddocks, where I saw some promising youngsters for the Derby. I was not sorry when Lady Albemarle inquired of my wife how long we were going to stay. We had some dear old friends in the neighbourhood: Partridges, Surtees, Eyres, and others. Went to Hockham on the 22nd.

A day in London on business. By rail to Chesterford, and chaise to my friend Alexander Cotton: the same who, as a lieutenant, was capsized with me at the mouth of Portsmouth Harbour in October 1830, he having now succeeded to the Hildersham property. Cotton’s house very comfortable; his claret uncommon good.

Rode after breakfast to Newmarket. In my father’s stables saw “Emperor,” “Smuggler Bill,” “Little Dorrit,” “Sir Rupert.”

Cotton and self to Newmarket.

[34]

Left Cotton to visit the Partridges at Hockham. Met at Harling Road by my old shipmate George Partridge.

Out shooting. I killed eleven partridges and one pheasant.

Champion Partridge came over. With the exception of a couple of days with George Birche’s Harriers had a capital week’s shooting.

Walked over to Larling Parsonage, where I found my old friend Colonel Eyre, 98th, with his brother Edward the clergyman.

George Wodehouse, Charles Partridge, and I rode over to Quidenham to see the brood-mares and young stock. Left Hockham for London. I was now in possession of a couple of hunters. Intending to enjoy myself, sent them on to Newbold, having business in London.

From London by rail, in company with Joseph Hawley, George Payne, Shelley, Greville, and other turf men to Chesterford. They to Newmarket. I to friend Cotton.

To Newmarket. Racing particularly good. Cambridgeshire stakes won by “Alum.” Twenty-eight started, beating “Baron,” the winner of St. Leger, and Cæsarwitch, etc.

This morning’s racing good. Backed my father’s colt “Radulphus” in the Glasgow, and lost my money.

Went with Harry Skipwith to Warwickshire Hunt; meet at Stonleigh Park, a beautiful place. Next day to see the Athelstane; meet at the Cross. Some pretty fencing from cover to cover and plenty of foxes.

Sent horses to Leighton Buzzard. A hearty welcome by Delmé Radcliffe at Hitchin Priory. The Eliot Yorkes staying there.

[35]

Having sent horses on with Delmé Radcliffe, to Brand’s hounds, Delmé having been Master of Hounds was proud to mount “Heki,” and delighted with him, as I was with my “Tom.” The run good for this country. We went and returned in a yellow post-chaise.

Mounted by Radcliffe. Went with the Harriers on his “Touch-and-Go”; supposed to be the best pack of the sort in England. Good for pastime, but it does not do after fox-hunting.

With Brand’s hounds: rode “Heki,” nothing particular by way of a run. Pleased with my horse though.

Harriers met at the Priory. Pretty and fast thing. Radcliffe hunting them.

With Brand’s hounds. Rode “Tom.” Found at Boxwood. Good run of 52 minutes. Was to the front the whole time. Radcliffe got the brush for my wife in commemoration of “Tom’s” performances. Killed at Yardley.

A right good run on “Heki” with the Harriers.

In afternoon rode “Tom” with the Harriers and had an excellent run of 50 minutes, the hare running better than many foxes.

Sent “Heki” on to meet the Cambridgeshire at Shear Hutch. Sharp run over heavy country. I got the brush.

No meet. Rode to see the Charles Radcliffes at Halwell.

With Radcliffe to meet the Puckeridge at Bedlington: a sharp thing. Got a cropper, but was in time to get the brush.

By rail to Burnt Mill, where I met Henry Seymour and Brice Pearse, who took us to Gilston Park, a nice old place he had hired for farming purposes.

[36]

Seymour and myself to meet the Puckeridge Hounds at Pelham. Rode “Heki”: a good gallop, leaving off fourteen miles from home.

With Brice Pearse to a city stable. Ostler brought out an Irish chestnut mare just under fifteen hands. On my inquiring if she could jump, a six-barred gate was placed across the paved passage road leading to the stables, which she jumped without trouble or hesitation. I paid £23 for her, and named her “Ticket” because she cleared the gates. She could not walk, but persevered in a jog trot to the end of the longest day. End of season, sold her for £70 to the Pytchley Hunt for a whip’s horse.

An idle day; mostly passed in the stable. Rode Pearse’s pony to Harlow with Henry Seymour.

Henry Seymour and I posted twenty-two miles to meet of Puckeridge Hounds. Had sent “Heki” on; a good run well worth the distance.

By early train to London and on from Euston Square to Catton Hall. Fred Horton met us at the station.

Catton, a nice old place. Pretty grounds—good stabling. Drove with Fred Horton in a dogcart. Granville Loch arrived.

Four guns. Bromley, Horton, Loch, and self to shoot. Pretty shooting: 42 head returned. I bagged 2 rabbits, 5 pheasants, and 11 hares. Fred Horton shot, as he thought, a hare creeping in a hedge, which proved to be a fox. Gave one of the beaters half a sovereign to bury it!

Stormy morning. Rode “Ticket” to meet of Meynall Ingram’s hounds at Gorsley Ley. Found immediately; was fortunate in getting well away. Pretty run for some twelve miles in an enclosed country. Long ride home.

[37]

The Donnington Hounds met near Derby; rode over to Osmaston to dine and sleep.

Sat with Lady Wilmot. My China boy “Chopsticks” much grown and very spoiled.

After breakfast rode back to Catton by Twyford Ferry: best road for riding.

Ingram Meynall’s hounds meeting at Drakelow. Mr. and Lady Sophia De Veux. Rode “Ticket”: bad scenting day, and huntsmen no great things. Ergo no run; though a find at Drakelow.

Rode “Heki” with the Atherstone. Meet at Warton; much pleasanter having a companion to ride to covert with. Two good runs; though a rainy afternoon.

General A’Court to dinner with a handsome daughter.

Took leave of Lady and Miss Horton. I rode “Heki”; groom on “Ticket” to Osmaston. Fred Horton took care of wife by rail. Lord John Russell unable to form a ministry.

Christmas Day. My first in England for some time.

The Donnington Hounds met at Cork Park. A beautiful place belonging to Sir John Crewe. “Ticket” fell at a fence and gave me a cropper.

Wife to Newbold Vicarage. I on to London, en route for Hockham.

[38]

Shore Time—Study Steam

At Hockham shooting.

By rail to Rugby and on to Newbold.

Mounted Grey Skipwith. Hunt with the Atherstone at Coombe Abbey. A goodish run. “Heki” a trifle lame.

Departure of Skipwiths in various directions, preparatory to the Warwickshire Hunt Ball.

Grey, Sidmouth, and I to meet the Pytchley at Crick. Certainly the finest run I had witnessed; George Payne giving me the brush.

Went shares in a pair of posters with Grey Skipwith to meet the Warwickshire at Shuckborough. “Ticket” sent on from Newbold. Found, and fell at a brook.

At Admiralty. Saw Lord Haddington. By steam to Woolwich. Only time to look at Terrible of large dimensions. Dined with Frank Collier.

Breakfast with Tufnell and Fred Horton. Attended dinner given by Naval Club to Lord Haddington on leaving Admiralty.

Up early for Rugby, where I had “Ticket” and hunting things sent. With the Warwickshire Hounds. Meet at Dunchurch. Capital run. Returned to Newbold.

[39]

Rode “Heki” with Grey Skipwith to Leamington. Took his mare and £30 in exchange for “Ticket.”

“Heki” falling lame, left him at Leamington and returned by rail to Rugby.

Took leave of Newbold. Established ourselves in lodgings at Leamington, for wife to be near Doctor Jephson. Horses at Stanley’s. “Heki” still lame.

Grey Skipwith came to dine and sleep. Letter from Mrs. Rowley announcing death of grand old Admiral Sir Josias, and enclosing a copy of his will, in which, should he survive his wife, after legacies, he had left everything to me—a kindness I had no right to expect.

Leamington full of lame hunters. By train to London.

Horton appointed to command of Cygnet, 6 gun brig, on coast of Africa. Attended levee of First Lord.

Great naval dinner at Thatched House Club. Prince George of Cambridge there.

Eleven train to Leamington. Wife better.

Rode with Grey Skipwith to see the Steeplechase at Southam. An amusing scene, but Leamington is not the most amusing place for a man who cannot keep horses.

Sold “Heki” for £15. Once refused 100 guineas!!

Dined with First Lord of the Admiralty.

By steamboat to see Frank Collier at Woolwich. He, Nic Lockyer, and I went over the Terrible, an enormous vessel, 1847 tons, 800 horse-power.

News from the Enlightened States. More warlike than ever. Lost no time in tendering services to Lord Ellenborough.

Met Sir Charles Fitzroy, with boys, Augustus [40] and George, grown into men: little Mary into a tall handsome mother of three children.

At Leamington. Dined at Lady Farnham’s: grub good, but seven ladies!! Saunders and self only gentlemen.

To Coventry races. Racing good as far as horses being well matched. Rough attendance.

Sported phaeton and pair of horses for the three days’ racing.

Delmé Radcliffe, Gore, and two Skipwiths to dine with us.

Steeplechase Day. Leamington full of ’legs and all sorts of rogues. Party of six to dine. “Grand, for us!” First-rate steeplechase.

Acted as chaperon to Amelia Williams; she riding Wood’s horse. Warwickshire meet at Stonleigh, afterwards steeplechase at Southam.

Bury came to us from London to go to the second ball: he dancing mad.

A good steeplechase at Warwick—country heavy—“Pioneer” winning—a splendid horse.

Mounted J. Wood to see the meet at Ladbrook.

Dining with Stephenson, Fox Maule, Lord Ebrington, Maria, and brother Edward.

Dined with the Duchess of Inverness; large party.

Talk with Lord Francis Egerton about Brooke and Borneo. Constance frigate offered to Walker, who appears undecided. Dined with the Hawleys—family party. That beast “Chow” dying.

Went to Woolwich to look for lodgings for my studying steam. By Frank Collier’s advice closed with a Captain Dwyer—not much; however, the best.

Took leave of Fred Horton at the club, lucky that he has not more than a year to run in Cygnet [41] on the coast. Dined with Ralph Brandling; Adelphi afterwards.

By express to Portsmouth. Dined with the Hyde Parkers in Dockyard; Admiral in great form.

Dined with the Gores, who have been very kind to us. Fare-thee-well Leamington. With horses and money I should find you more agreeable.

Took departure for London. Letter from Brooke, and news from Borneo not pleasing to Wise. Government slow in acting for him. To Droxford by 3 P.M. train.

Took our departure from our snug little Droxford. In London by 2 P.M. Got Mrs. Rowley her pension at Admiralty. To Woolwich by steamer. Took up quarters in Captain Dwyer’s house. Wife not taken with our new abode.

To church in a sail-loft in the Dockyard. Went to Greenwich in the afternoon: looked at houses.

To Greenwich. Decided on No. 17 Croom’s Hill at £150 per annum; nice situation, looking into the Park.

Letter from Commander Dwyer refusing to let me off under three months’ rent! Unlucky dog that I am, £36 thrown away. So much for having to deal with a gentleman.

To see the Horse Artillery exercise. Edward Coke and Sir E. Poore to call; they going to West Indies in June for amusement.

To London. Saw my father; well in health; going to Newmarket.

Receiving a letter from Sir William Symonds, asking if he might nominate me to command his Spartan, started for Somerset House, and found from Edge that I was wanted, as in case of Constance, as a second string to his bow.

[42]

Attended the meeting of the Committee for the Foundation of a Church Mission-House and School in Borneo. Some large subscriptions received.

Again over to Greenwich; hard bargain with Mrs. Kemp. Georgie Crosbie and early dinner.

Took my first lesson in steam at Woolwich.

Hearing that a foreigner was inquiring after me, avoided him; it turned out afterwards to be an old Spanish friend, General Mazzerado of Barcelona, who stopped to dinner.

By Templer heard of a most diabolical massacre committed in Borneo Proper.

Commencing steam study in earnest.

A Princess born. (Princess Helena.)

Breakfast at half-past eight. Start at nine to be in Dockyard by ten. Pleasant enough while the weather is fine. Dined at Greenwich Hospital with Sir Robert Stopford to celebrate Her Majesty’s birthday. Pleasant party.

Derby Day, and I not there. Won by Mr. Gully’s “Phyrrus.”

The sad news of the massacre of Rajah Muda Hassim and family, and his gallant brother, Budrudeen.

Greenwich Fair. Joined George King and his party in a small Whitebait dinner at the “Crown and Sceptre.” Paraded the Fair afterwards.

Dined with Sir James Gordon, Lieutenant-Governor of Greenwich Hospital. Though he lost a leg in Hostes’ Lissa frigate action, Gordon frequently walks from London.

Attended the wedding of Amelia Williams and Mark Wood—also to déjeûner given by the Bulkeleys. Lovely day; pretty wedding; good breakfast; everything right.

[43]

Early dinner with the Hawleys. Tattersalls and Park afterwards.

To Woolwich Dockyard, Dined with Colonel Parker to meet kind friend, his brother, the Admiral.

Dined with Commander and Mrs. Dalyell in the Hospital. He was for nine years a prisoner of war at Verdun; released when Napoleon I. went to Elba. Anyone interested in the record of a sailor’s life during the end of the last century and early part of this should read that of my old friend, who was now a pensioner, with apartments in Greenwich Hospital.[1]

The Dalyells are kind people and have exceedingly good taste.

To Woolwich by steam, meeting on board Lord Selkirk, Captain Ross, and Ranelagh. Went to Arsenal. Georgie and Jack Crosbie and Grey Skipwith to dine.

An impertinent letter from Wise: answered him.

To Woolwich by steam.

Called on Sir James Gordon and on Sir Watkin Pell.

Sir Watkin Pell—a wooden leg, and a wonderful clever pony on which he used to ride on a three-plank bridge when visiting ships fitting out in dock.

Dined at the Stopfords.

Dined in London with my father; returning afterwards to Greenwich.

We went to see the muster of Greenwich schoolboys. Interesting sight. 800 of them dining in same room. Ministers about to resign.

Represented Brooke at the christening of Templer’s boy, named James Lethbridge Brooke.

[44]

Business at Admiralty. Saw Lord Auckland about Borneo.

Concocted a letter for Lord Auckland, recommending possession of Labuan.

Capital dinner with Sir Watkin Pell. To the Artillery ball at Woolwich. Nothing could be better done.

Dined with Sir Robert Stopford. Greenwich ball in the evening; very good.

To London with Jack Templer to see Lord Auckland concerning Brooke.

Very mysterious. Government evidently doing something. Afraid, I think, of Mr. Hume.

To steam studies. Met Board of Admiralty in the Dockyard. Received intimation that my services would be again required in Borneo.

Skipwith and ourselves to dine with the Newdigates, who have pretty place at Blackheath.

After studies visited famous mulberry tree in Collier’s garden.

Students in steam met at Blackwall to examine the machinery of the Sir Henry Pottinger, a merchant steamer.

Accompanied Captain Stewart in the Trinity yacht to meet the Admiralty Board at Gravesend to inspect several plans for lights to be carried by steamers at sea to prevent collision.

Invited Roberts to dinner, to meet Edward Rice, who did not arrive until late.

Rice to join Amphion should I get her!

At Admiralty to stop Comber being sent off to sea. Partly succeeded. Came back to dine with Sir Watkin Pell.

Woolwich, preparatory to being examined by [45] Lloyd. Passed an hour in the Superintendent’s mulberry tree!

By Gravesend steamer to Purfleet, where Sir Thomas Lennard sent his carriage to take us to Belhus for three days; brother Tom having married his daughter. Large party; hearty welcome. This is a nice old-fashioned place. Our room the one in which Queen Elizabeth slept.

After luncheon we were taken a drive with the team round the country. Went to Mr. Tower’s place: he has some fine old pictures.

Took leave; pony carriage taking us to Gray’s Pier. Embarked for Blackwall loaded with game and fruit.

I dined with the Artillery mess at Woolwich.

To London to attend Borneo Church Mission. Capture of Brunei. Saw Mundy’s letter to Baillie Hamilton at the Admiralty relative to the affairs there.

On return found Edward Rice from Dane Court.

To Admiralty to deposit with Lord Auckland my father’s correspondence with Lord Haddington relative to my not getting the C.B.

We took the two charming Dalyell girls to the Woolwich Garrison races. Very good fun: heats and that sort of thing; gentlemen riders.

Visited Sir Samuel Brown of chain-cable notoriety, and saw several ingenious inventions.

To London. Wife on a visit to the Roes at Fulham.

Among the intimate friends of the Crosbie family were Sir Frederick and Lady Roe. His father was a well-to-do merchant residing in the City. My father amused me with the following:—As Master of the House he had to attend State occasions. On going to the City, Sir Frederick Roe [46] was so active with his mounted police as to draw the attention of His Majesty, who inquired who he was. Father informed the King that it was Sir Frederick Roe, the Head of the Police. His Majesty noticed another officer equally active, and very like Sir Frederick, who my father informed His Majesty was a younger brother, likewise in the Police, who helped his brother on these occasions, and they went by the name of “Hard” Roe and “Soft” Roe. This amused His Majesty so much that he wanted to know about the father. This rather puzzled my parent, who, having volunteered so much, did not like to plead ignorance, but answered “They call him, Sir, Paternoster Row!”

Ascertained at the Admiralty they had no idea of forming a Settlement on the Bornean coast.

Power of a “wise” confidential agent beginning to tell.

To Ranelagh House, Fulham, to join wife at Sir Frederick and Lady Roe’s.

Having been invited by Sir Charles and Lady Mary Fox to dinner at Addison Road, sent to Greenwich for clothes. Wife dining with the Dalyells.

Found letter at club from Symonds, stating that he had applied to Lord Auckland to appoint me to Cambrian for trial with Thetis.

Dined with Sir Robert Stopford; a large party.

To Admiralty to inquire about the Cambrian; find I am the favourite, Lord Auckland hovering between Smith and myself for the appointment.

Dined on Guard at St. James’ with Colonel Codrington.

Nothing decided about Cambrian, Lord Auckland waiting for Sir Charles Adam’s opinion. Still hope.

[47]

Dined at the Newdigates.

Reports of my appointment to Cambrian; hope they may prove true. Stephenson writing to thank Lord Auckland.

Dined with John Doyle and Lady Susan North.

To see Admiral Dundas. Early proposal of appointing me to Amphion. No fancy for her, while there is a chance of Cambrian.

We dined at Colonel Parker’s. On return found letter from Dundas, a damper on hopes of Cambrian.

Baillie Hamilton in the Rangers’ House. Commander Henry Eden married to Miss Rivers. Wish to get Lieutenant Rivers as my First.

Dined with Lord Auckland.

At Dane Court with the Rices; like Dane Court and all its people. Everybody receiving me so kindly; the children too, as if they had known me all their lives.

A walk with Fanny and Anne in forenoon. Afternoon to Dover. Saw 43rd and H. Skipwith inspected on the heights.

Received twelve guineas due to members of Old Navy Club, Bond Street. Retirement list out, of 180 Captains.

Dined with my father. Shireff wanting me as Flag-Captain.

To Woolwich to see Sir Frank Collier for last time as a Commodore.

Dined in London with Stephenson. Meeting Hastie and Sir John Hobhouse.

Lord Mayor’s Day. Promotion in Army and Navy. Dined with Admiral Dundas. Large party at Lord Auckland’s in the evening.

Club full in anxious expectation of “Gazette.” The greatest boon that has been granted to the Navy.

[48]

Dined with General Mundy and family. Disappointed about the promotions.

Dined with Sir Robert Stopford.

Farewell dinner with the Dalyells. We have been treated at Greenwich with the greatest kindness and hospitality.

Dined at Club. A meeting of old “Magiciennes,” Plumridge, Knox, Forbes.

Called for Stephenson at the Excise: with him to Cambridge, where, after having enjoyed much worth seeing, dined with Henry Coke: Augustus Stephenson and young Lord Durham of the party.

We slept at the University Arms.

Visited my brother George at his office, Downing Street. Chance of my being appointed to Amphitrite. Returned with Pearse to Gilston.

Brice Pearse mounting me; after several hours, without finding, finished with a fast twenty minutes with Conyer’s hounds. In first at the death, and got the brush.

Party to shoot. Keeper reserved best ground until too dark—only a small bag.

Took leave, after luncheon, of our friends. On a visit to the Rushs at Elsenham: a pretty place. Much taste and considerable expense in the making.

H. Byng, alias “Buckets,” with his wife to dinner.

By early train to London. In time to leave Euston Square for Newbold by eleven o’clock.

Sharp frost. Hunters more expense than profit.

Enjoyed Christmas at Newbold, sitting down twenty all told. Sir Grey presiding. Eight sons, five daughters, two husbands and wives and ourselves. The younger son—a nervous boy, studying for Holy Orders—was called on to say grace; after hesitation got up and said: “For what we are going to receive, [49] the Lord have mercy on us.” A more cheery Christmas could not be.

Having business in London, and hoping for employment, left my poor invalid under care of the celebrated Doctor Jephson, at Leamington.

To my second home, the Stephensons in Arlington Street.

Dinner off Norfolk turkey, and a hot devil by sister.

At Hockham shooting, with the Partridges, Charles, George, Paterson, and self. Shot with my new Westley-Richards. Much pleased with it.

[50]

Shore Time

As brother Tom could not, with increasing family, come to me, I went to his parsonage at Creake in Norfolk, where we were joined by my other clergyman brother Edward. Creake only a walk from Holkham.

This entailed visits to other dear friends; but as these have not much to do with the promised sailor’s life, must not detain readers.

Sunday.—Both brothers preached; I suppose the elder had choice. Reserved opinion.

Recollect some time ago, when brother Edward preached at Quidenham, venturing to remark that his sermon was rather lengthy. He replied: “It now lies at the bottom of a heap and you won’t hear it again for three years.”

Went out, fifteen guns, 1085 head.

Drove back with Napier, rector at Holkham, elder brother of Brooke’s Singapore friend.

Shooting the end of the park in the direction of Warham; twelve guns, 973 head.

Another good day’s shooting; 1073 head.

News of the safety of Edward Coke, who had been buffalo-shooting in the United States. Never once doubted it.

[51]

Tom and I drove to cousin Fred Keppel’s at Lexham, about eighteen miles. Hearty welcome. No better fellows than Fred and Edward Keppel, “the Cheeryble Brothers.”

Went out to enjoy the best shooting Fred had left. Six guns: Fred Fitzroy, Derrick Hoste, Fred, Edward, Tom, and self.

Wife improving at Leamington under Jephson. Fred Keppel and brother Tom doing magistrates’ business at Litcham.

Party breaking up. Fred Fitzroy dropping me at friend Rev. C. D. Brereton’s.

Took leave of Brereton. Drive of eleven miles to Creake. Bitter cold. Henry Coke arrived from Holkham.

To Bobby Hammond’s, now a rich banker; change from a mid’s berth.

Fred Keppel drove me to brother Edward’s.

Looked over the Quidenham Stud paddocks. Some old brood-mares and four yearlings. A colt, “Borneo,” promising looking.

Fred Keppel taking me back to Lexham, sent things to Anthony Hammond’s at Westacre.

Followed in afternoon. Charming place as well as host.

Anthony, Bob Hammond, Henry Coke, and others came to dinner.

Henry Coke and I took departure from Westacre, posting to Brandon, by rail to Cambridge. Henry having left the Navy had lodgings there: a quiet dinner with him.

To London; with Stephensons in Arlington Street.

Joined wife at Leamington.

To London. Father recovering from illness.

[52]

Letter from Admiralty requesting me to sit on a Commission to report on Naval Uniforms—Chairman, Rear-Admiral Bowles, C.B. Committee: Rear-Admiral Sir F. Collier, C.B.; Captains A. Fanshawe, C.B.; J. Shepherd; Hon. F. Pelham; A. Milne; Lord Clarence Paget; and W. F. Martin.

Poor Thistlewayte quite blind.

Rode to Collier’s new house at Wickham. Nothing more neat, complete, and comfortable.

Wife and I on a visit to Southwick. George Delmé came to dinner.

Walked from Southwick to Droxford, and afterwards to Rookesbury. Thistlewayte sending wife there in carriage. Good William Garnier insisted on our all staying at Rookesbury.

William Garnier mounting me, we rode to the Dean’s at Winchester. Sister Caroline out. Called on Walter Longs on our way back. Collier and Campbells to dinner.

On Garnier’s hack to see Hambledon Meet. Many friends, but a bad scenting day.

In break, picking up Wickham’s Admiral, Collier, on the way. Lunched with the Hyde Parkers. Sphynx in harbour after six weeks on rocks at back of Isle of Wight.

By coach to stay with Sivewrights, Symington.

Years since Edward Sivewright and I met. At Symington, canvassed for brother George.