[i]

A SAILOR’S LIFE

[ii]

[iv]

[v]

BY

ADMIRAL OF THE FLEET

THE HON. SIR HENRY KEPPEL

G.C.B., D.C.L.

VOL. I.

London

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1899

All rights reserved

[ix]

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| 1809–1822 | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Tweed, 1824 | 26 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Tweed | 46 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The Tweed | 55 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Tweed | 66 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| England | 92 |

| CHAPTER VII[x] | |

| The Galatea | 101 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The Magicienne | 119 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| The Magicienne | 127 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| The Magicienne | 147 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| The Magicienne | 153 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| England | 160 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| The Childers Brig | 165 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| The Childers Brig | 174 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| The Carlist Question | 184 |

| CHAPTER XVI [xi] | |

| The Carlist War | 192 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| The Childers Brig | 198 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| The Childers—West Coast of Africa | 202 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| Cape Coast Castle | 217 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| The Childers Brig | 226 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| A Rendezvous of Cruisers | 231 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| England | 246 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| Shore Time | 251 |

| CHAPTER XXIV | |

| Dido Corvette | 255 |

| [xii]CHAPTER XXV | |

| Dido—China | 269 |

| CHAPTER XXVI | |

| Dido—China | 277 |

| CHAPTER XXVII | |

| Dido—Straits of Malacca | 282 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII | |

| Dido—Borneo | 292 |

| CHAPTER XXIX | |

| Dido—Borneo | 311 |

| CHAPTER XXX | |

| Dido—China | 322 |

| CHAPTER XXXI | |

| Dido—Calcutta | 331 |

| INDEX | |

[xiii]

| SUBJECT | ARTIST | PAGE |

|---|---|---|

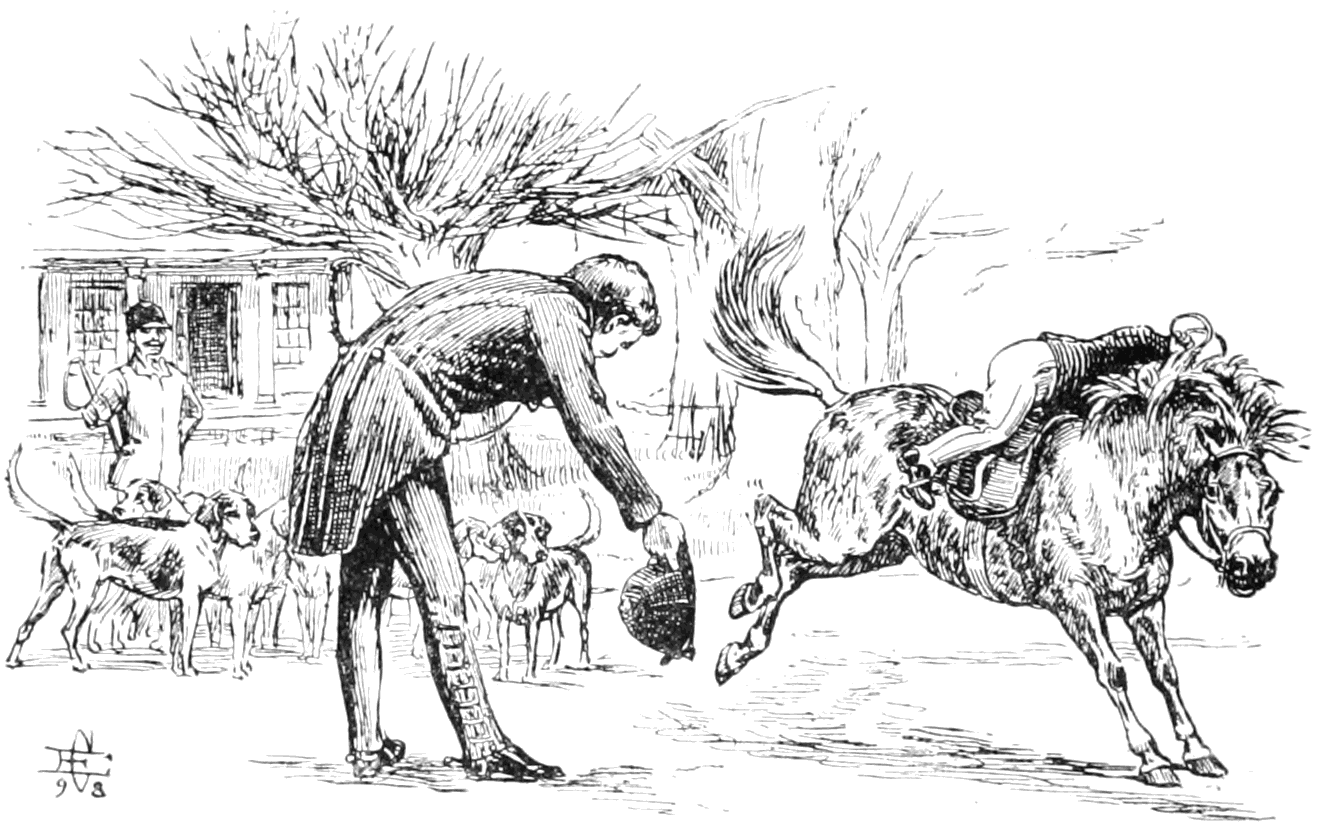

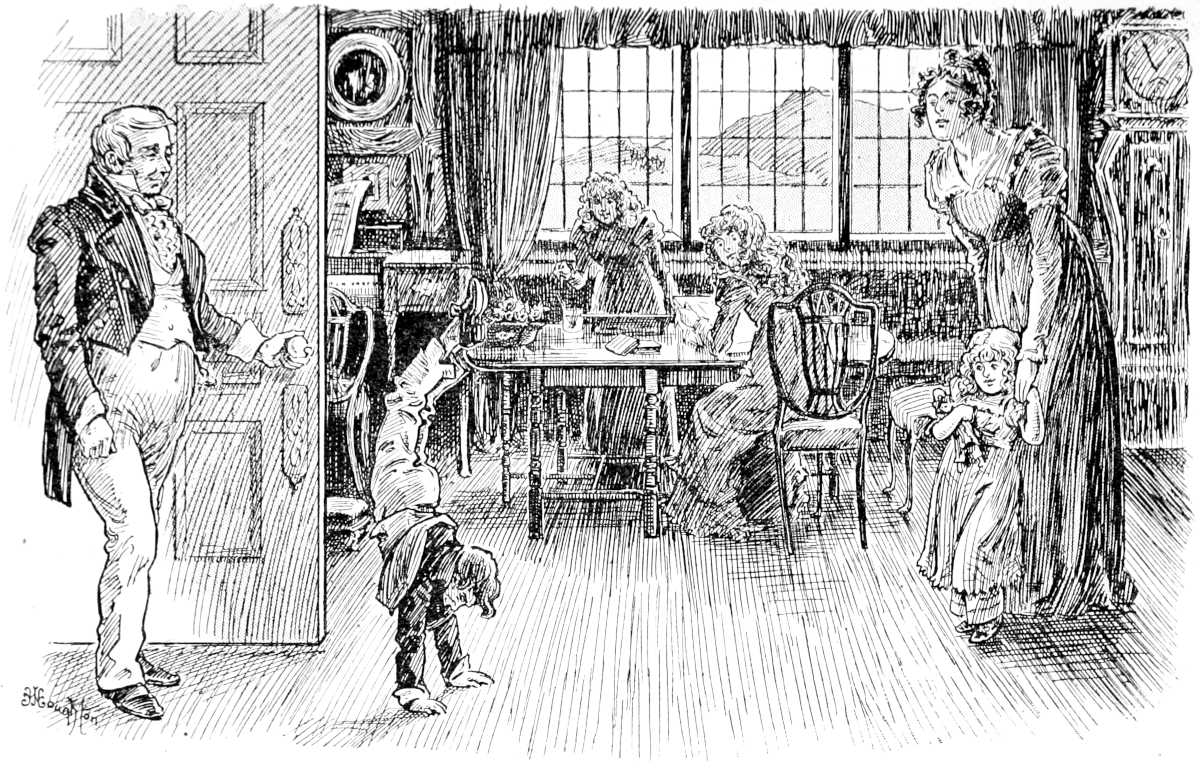

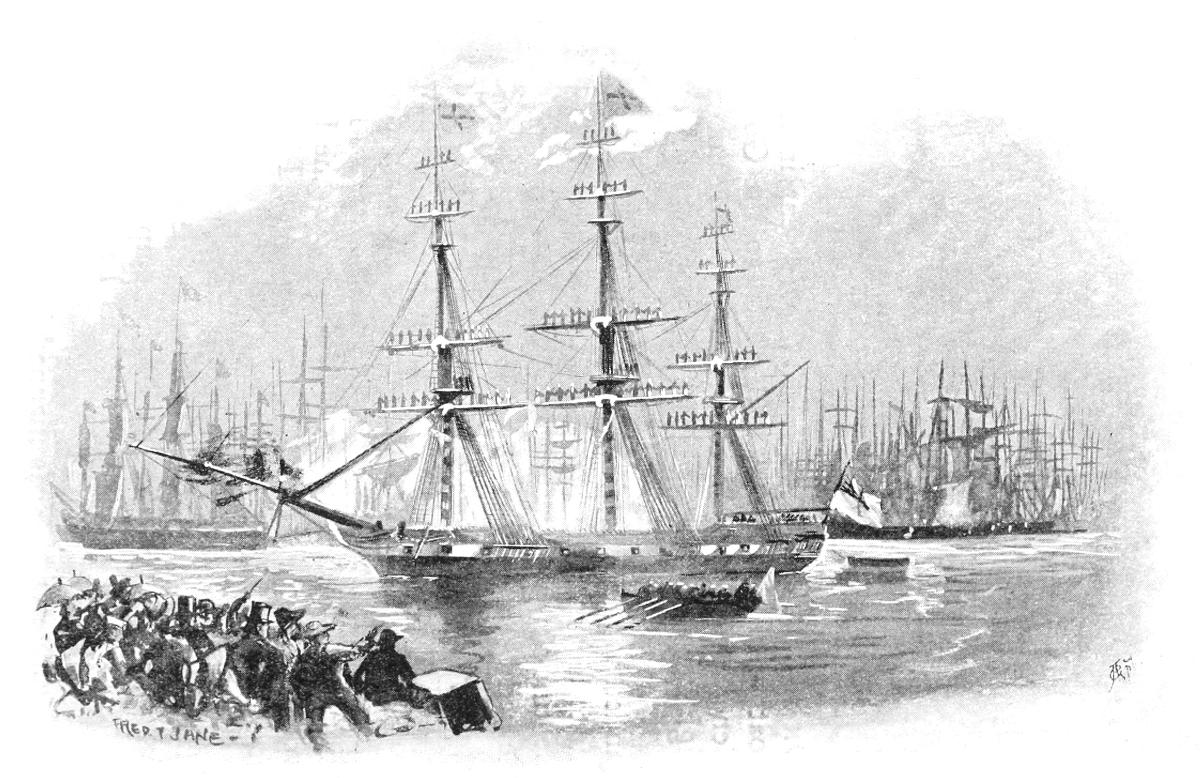

| “There was life in the ‘small thing’” | J. W. Houghton | Frontispiece |

| A Successful Operation | ” ” | 3 |

| Pio Mingo | E. Caldwell | 6 |

| Sir Francis Burdett | From an engraving | 8 |

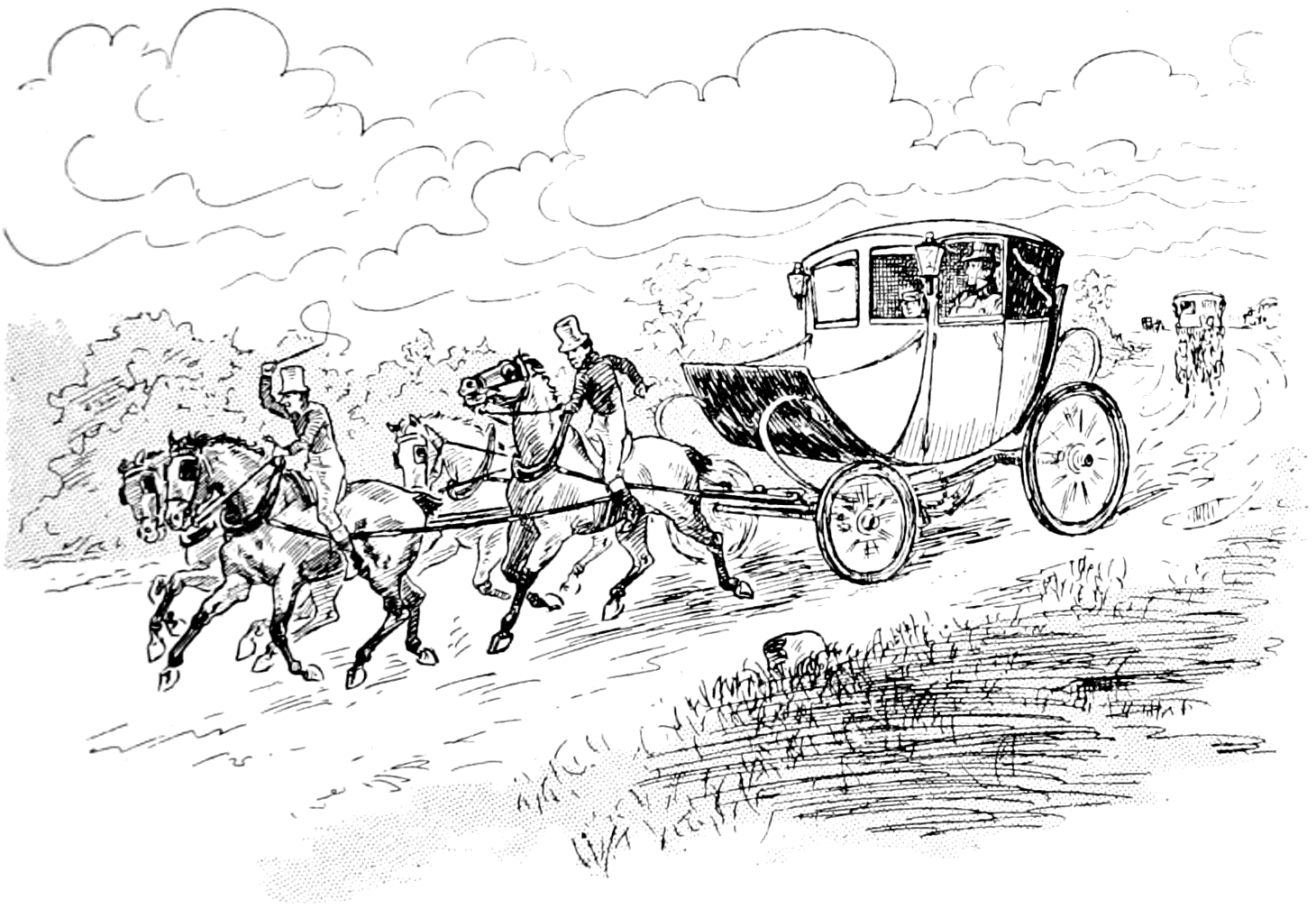

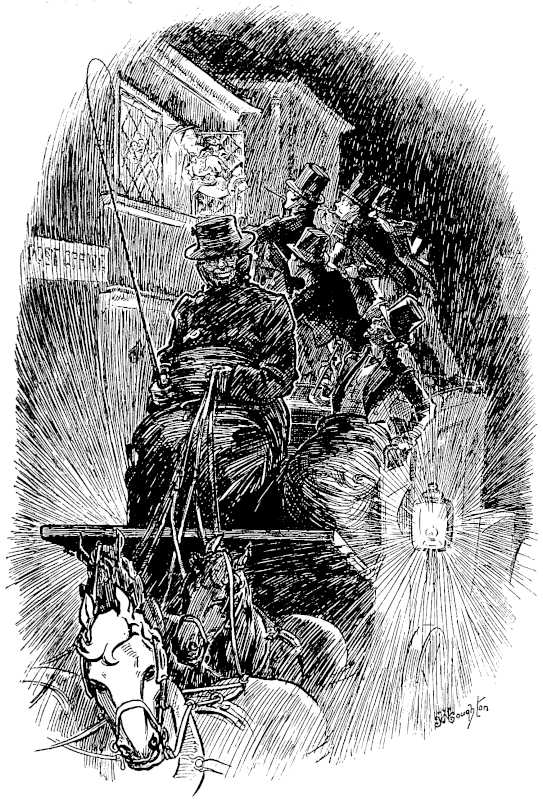

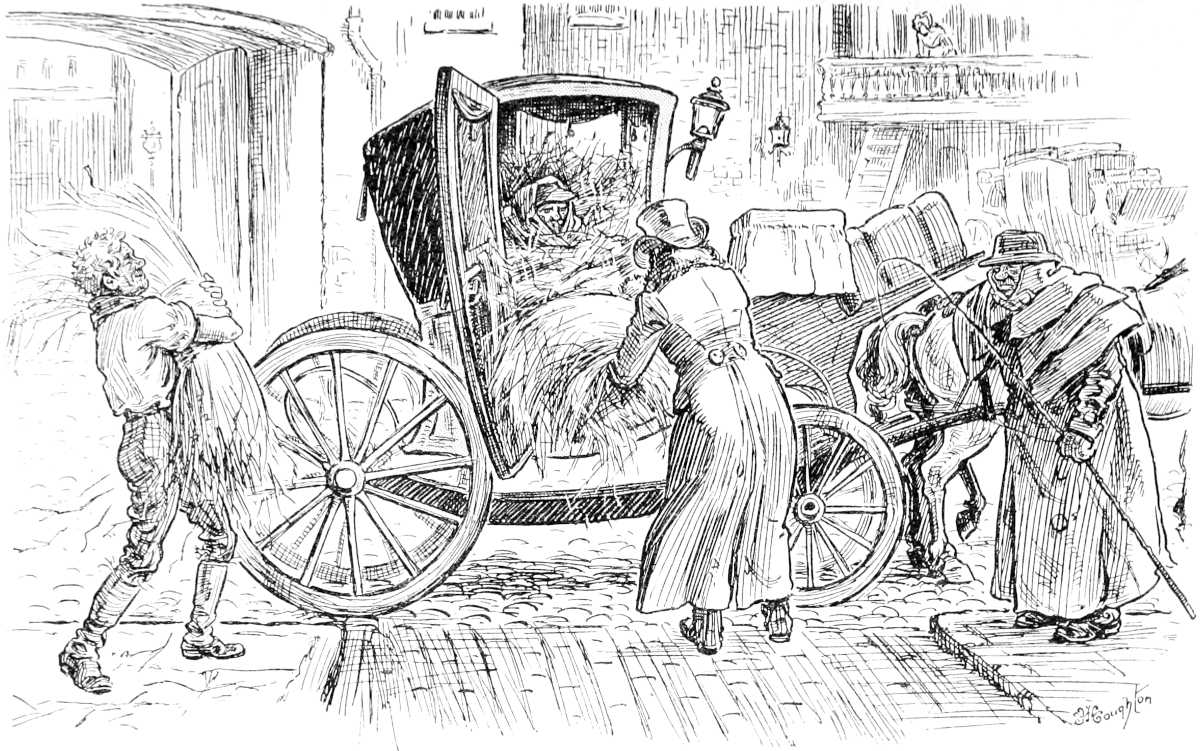

| Sir Francis Burdett’s Carriage | J. W. Houghton | 9 |

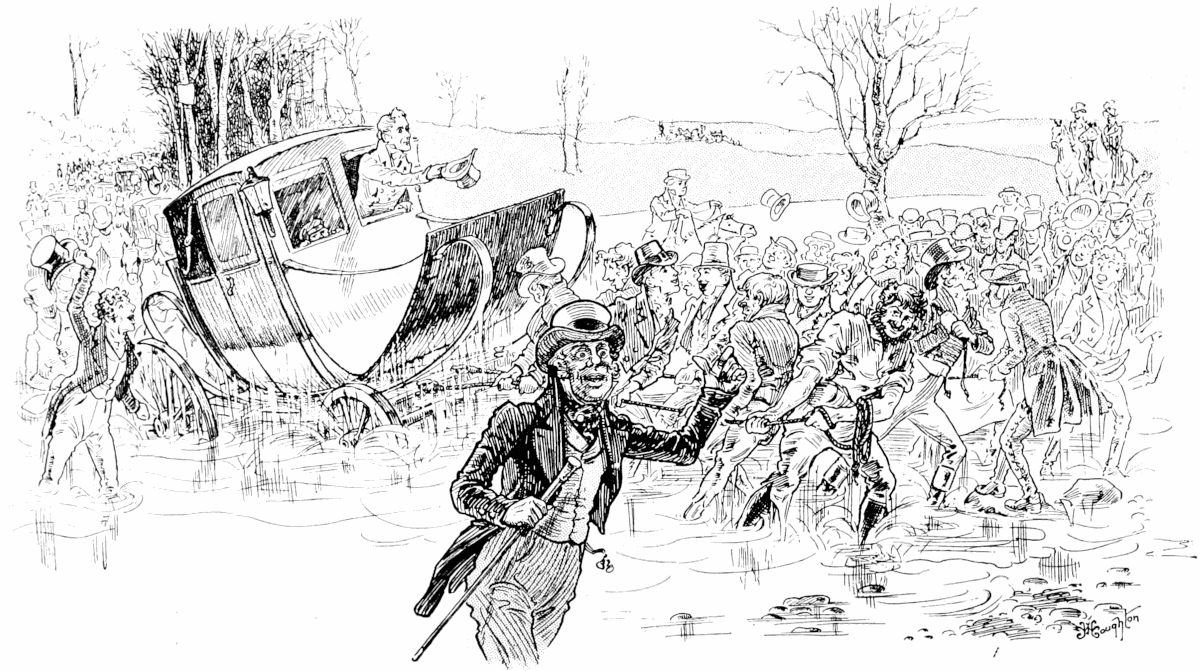

| A Compliment to Sir Francis | ” ” | 10 |

| Nelson’s Chair | ” ” | 15 |

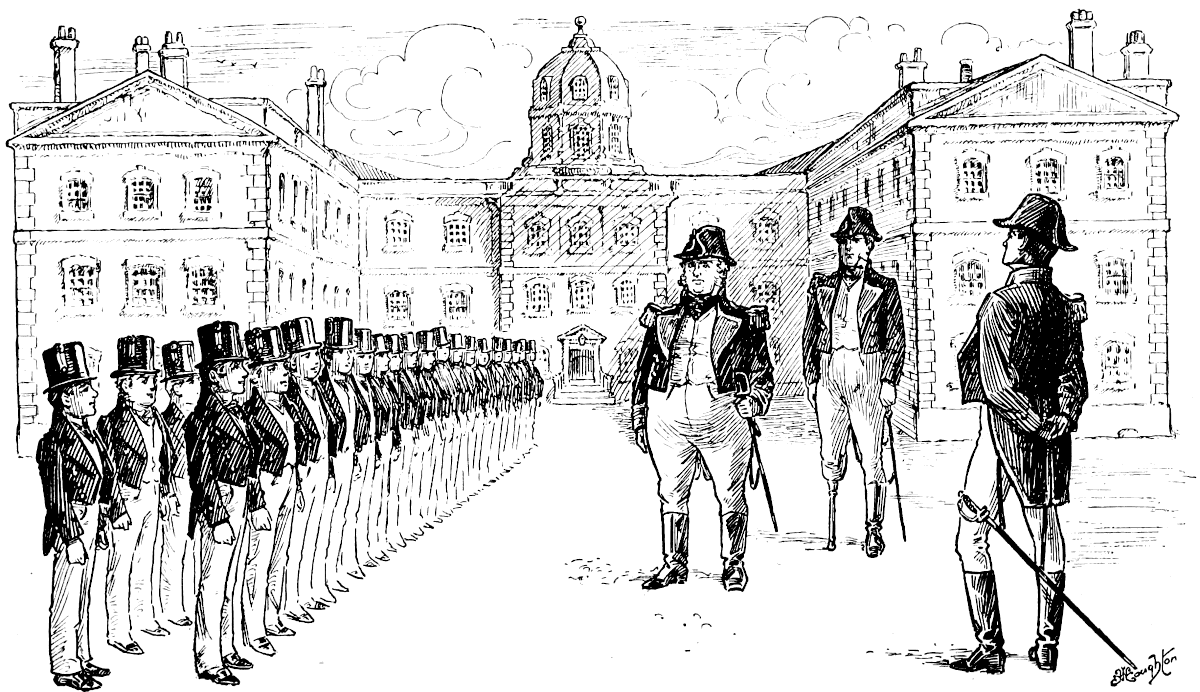

| Royal Naval College | ” ” | 18 |

| The Attack | ” ” | 21 |

| The Defence | ” ” | 23 |

| During the Examination | ” ” | 24 |

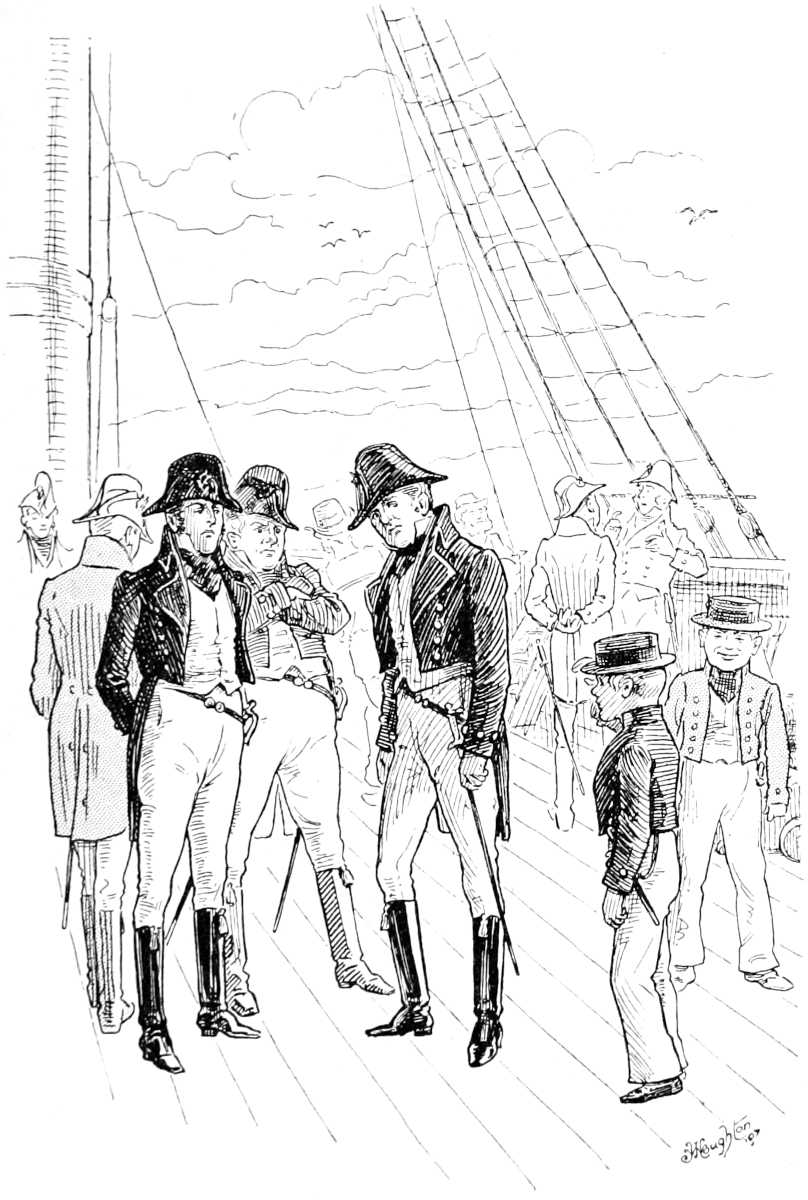

| Meeting the Captain | ” ” | 27 |

| Ship Mates | ” ” | 31 |

| Consolation | ” ” | 35 |

| Meet Lord Cochrane | ” ” | 37 |

| Arrested | ” ” | 50 |

| Vera Cruz | Anon. | 62 |

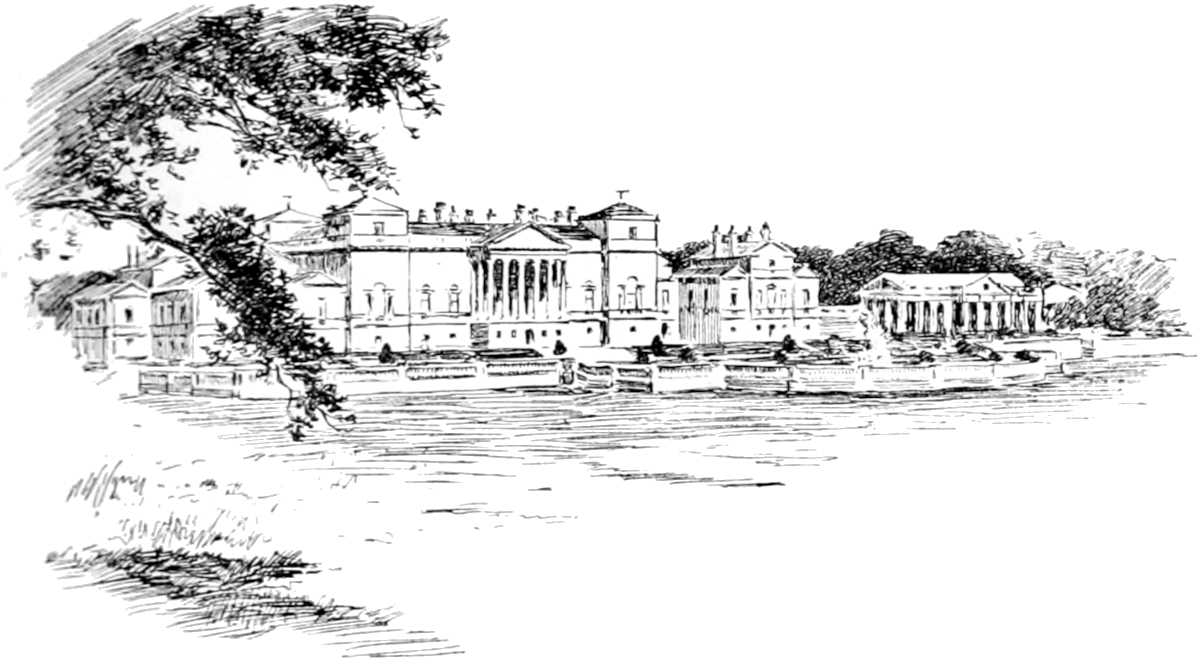

| Holkham | W. H. Margetson | 67 |

| View from Réduit | Lady Colville | 78 |

| A Colossal Tortoise | J. W. Houghton | 80 |

| Sir Lowry Cole | Nina Daly | 82 |

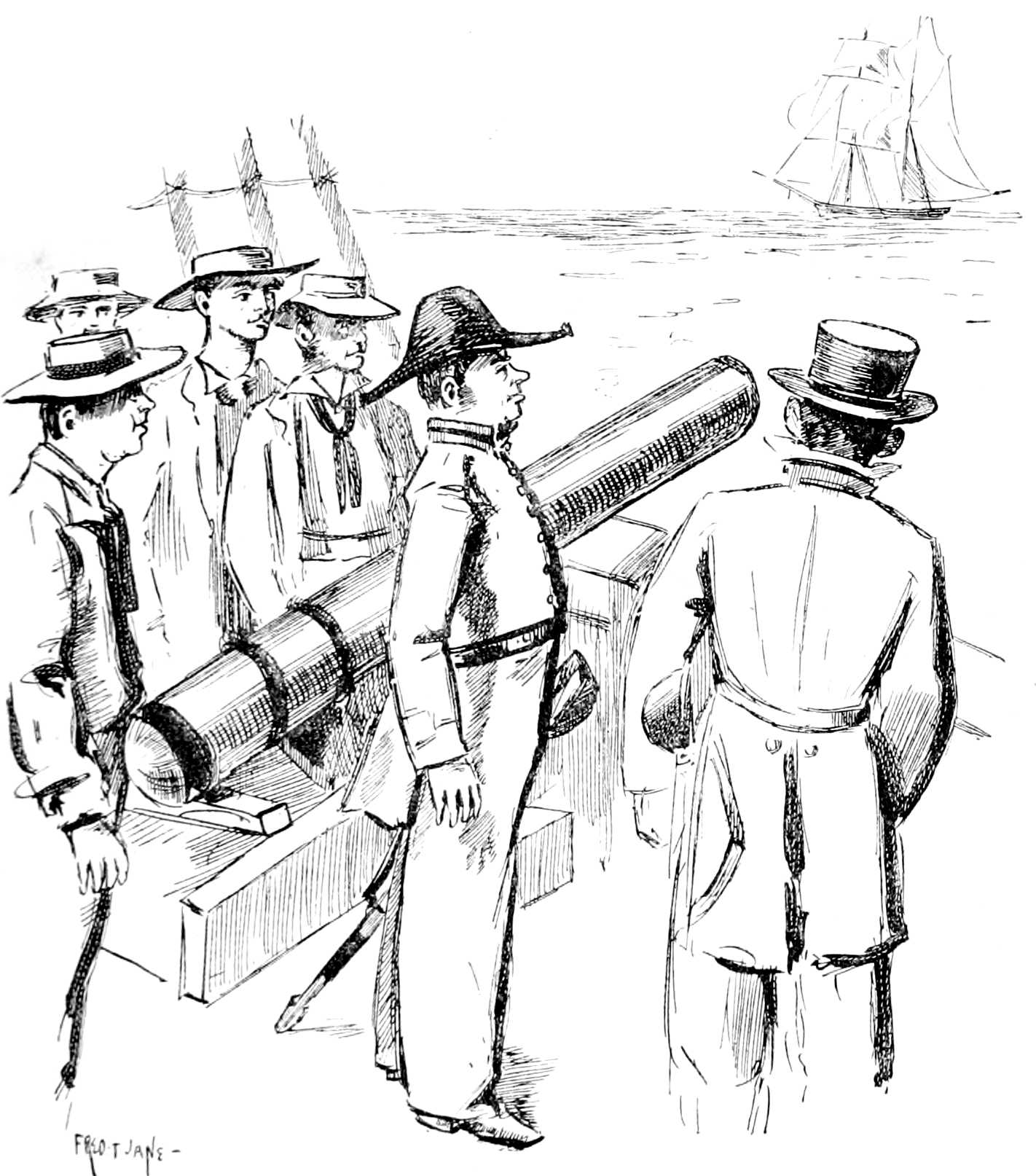

| The Device of Jonas Coaker | Fred. T. Jane | 83[xiv] |

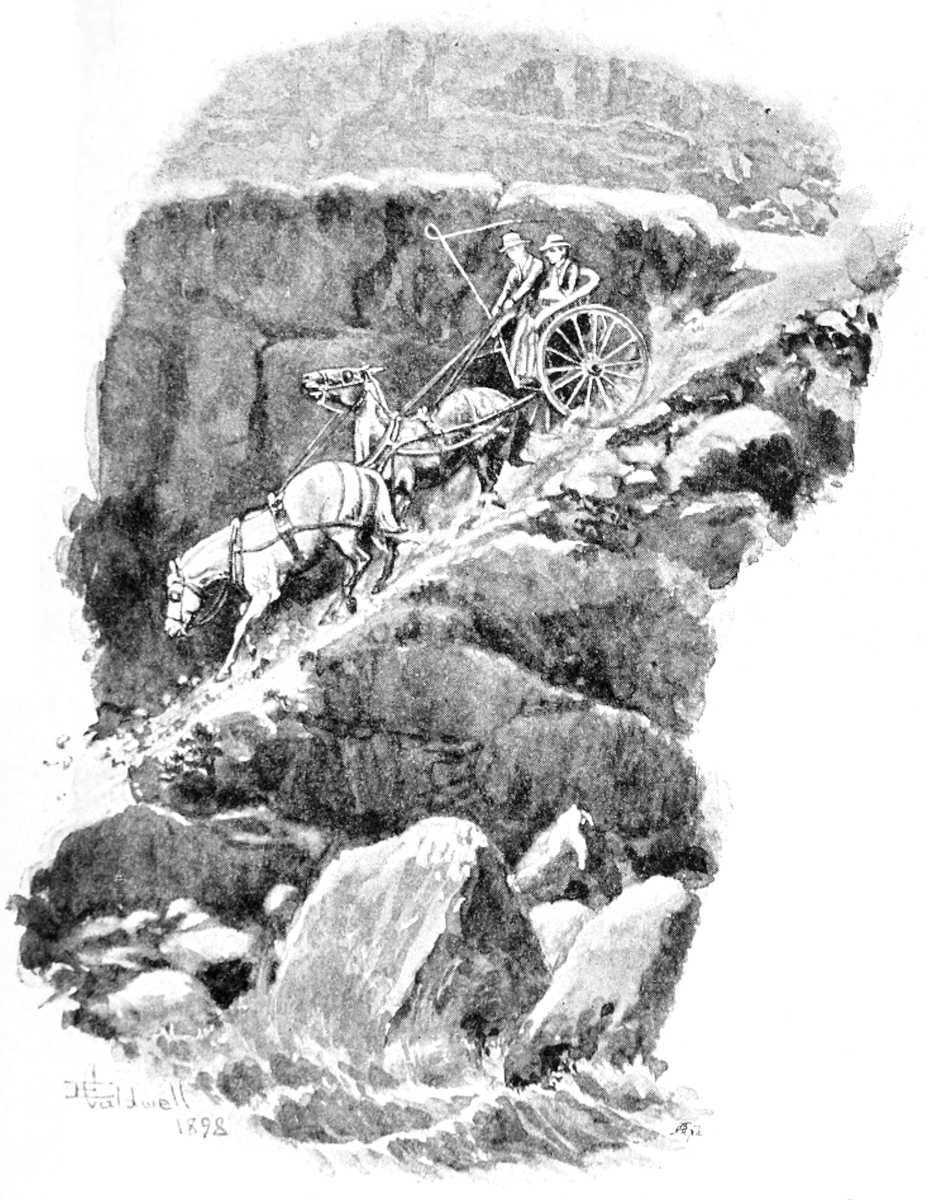

| “Keppel’s Folly” | E. Caldwell | 89 |

| Napoleon’s Grave | Anon. | 90 |

| At St. Margaret’s | J. W. Houghton | 95 |

| Nearly Frozen | ” ” | 99 |

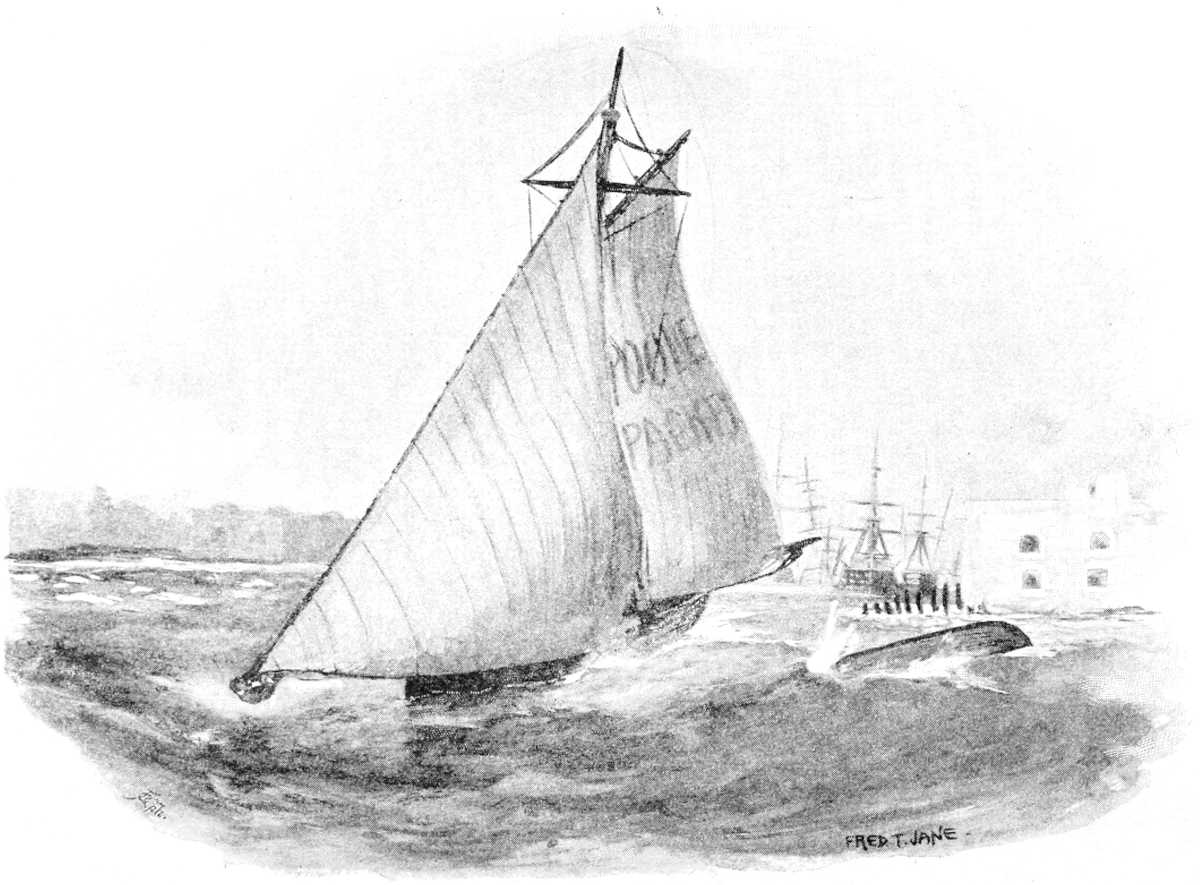

| The Poole Packet | Fred. T. Jane | 106 |

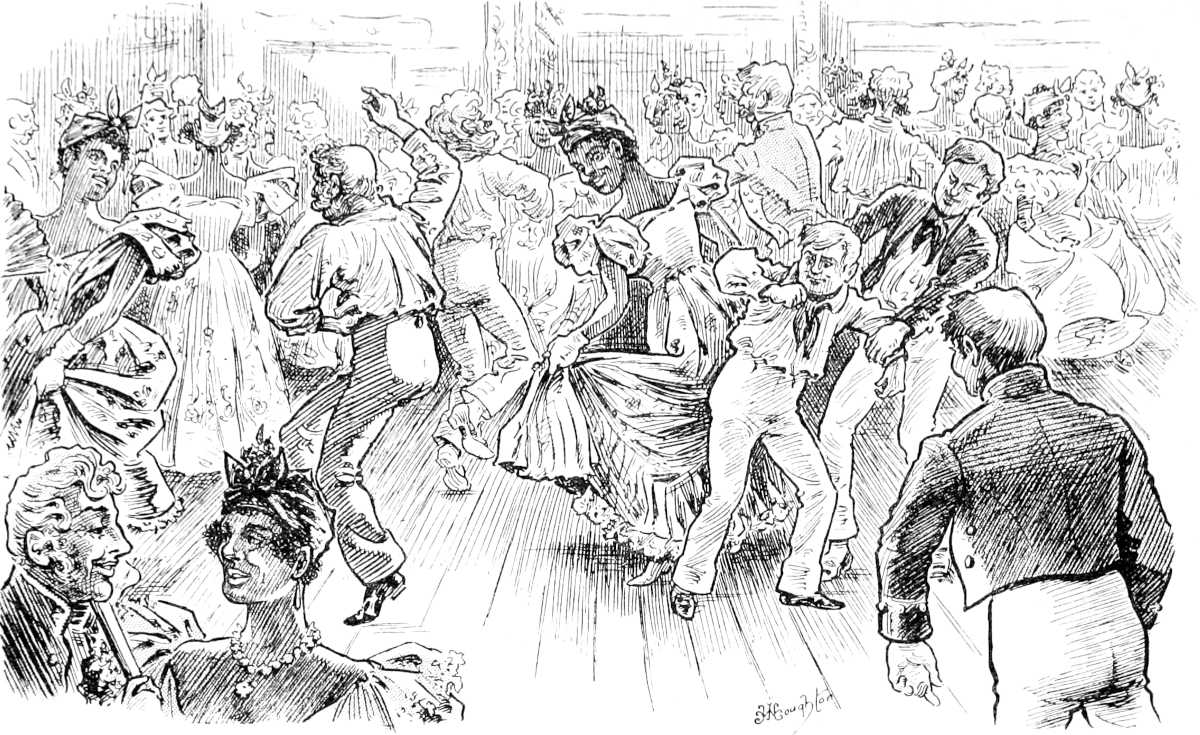

| The Dignity Ball | J. W. Houghton | 111 |

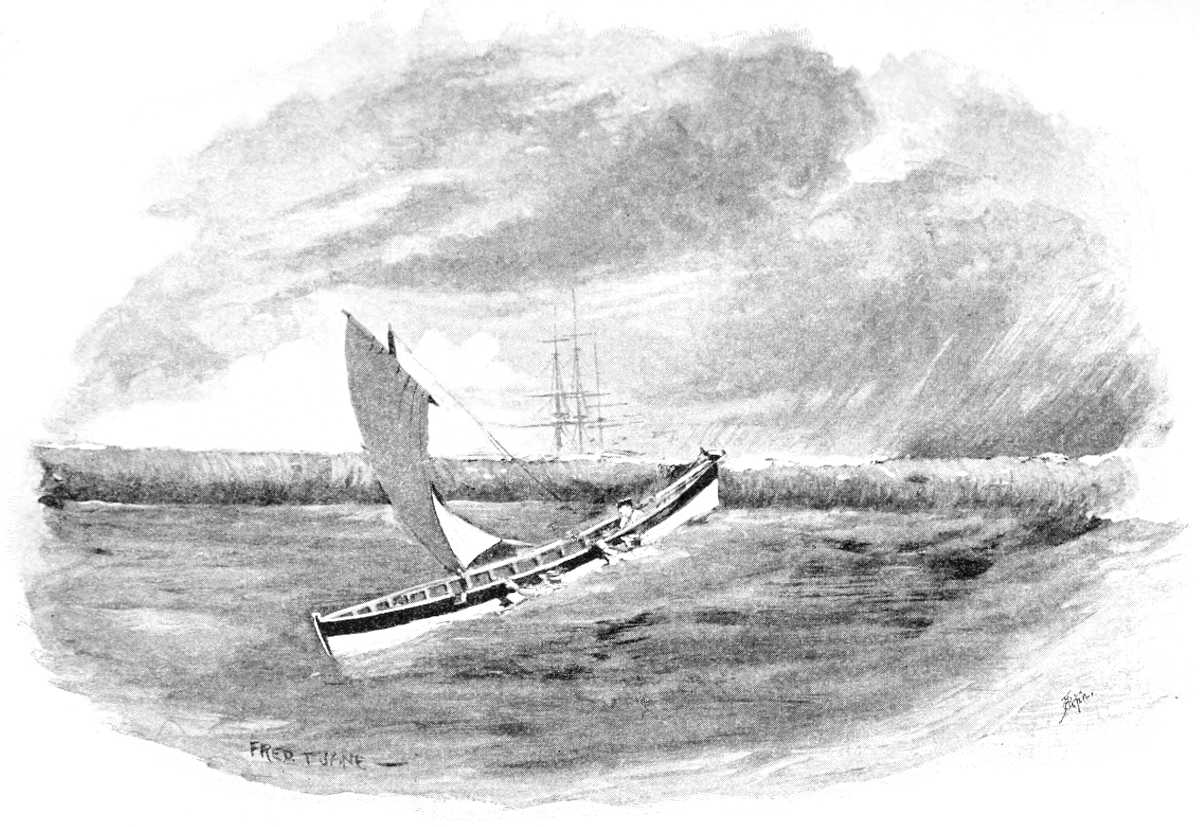

| Crossing Tampico Bar | Fred. T. Jane | 117 |

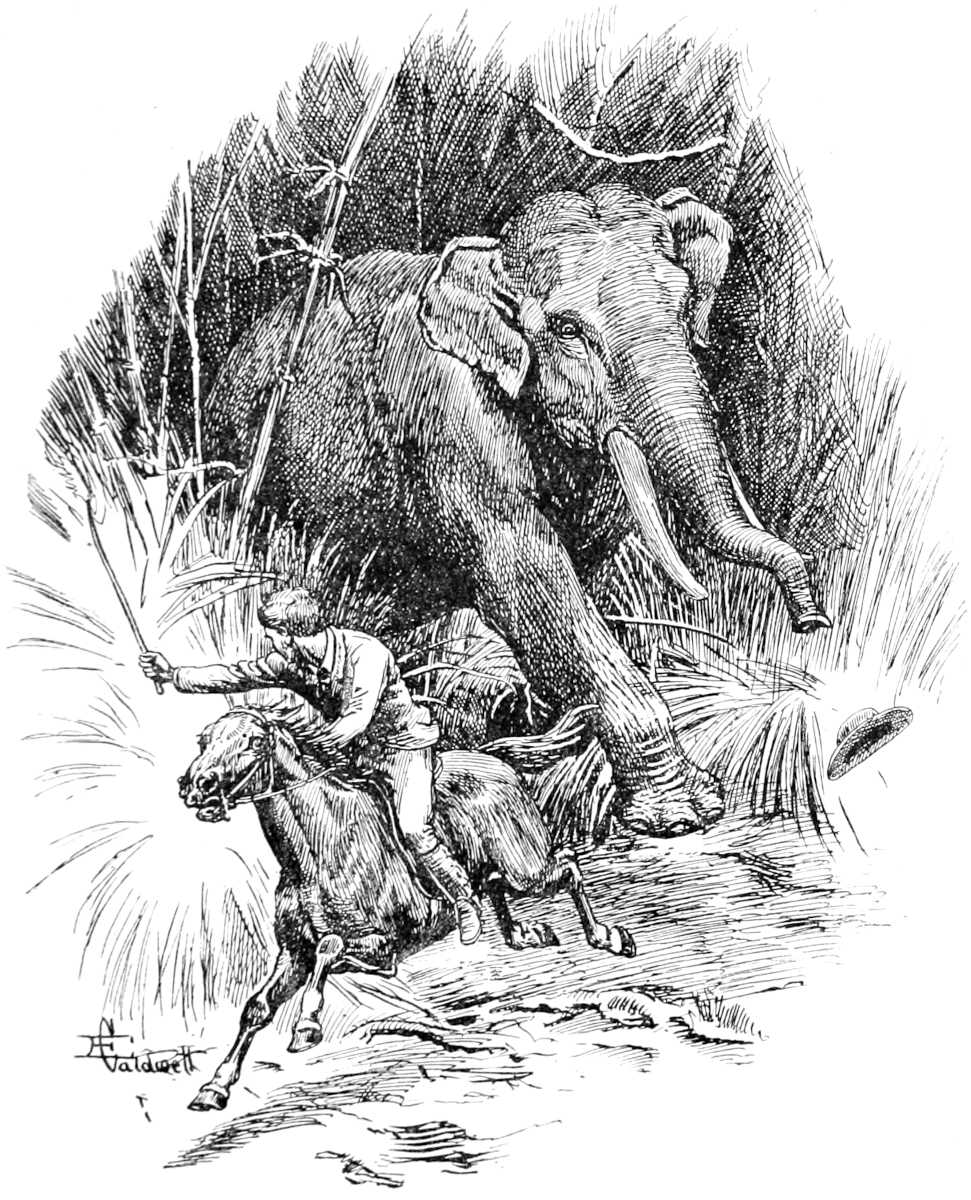

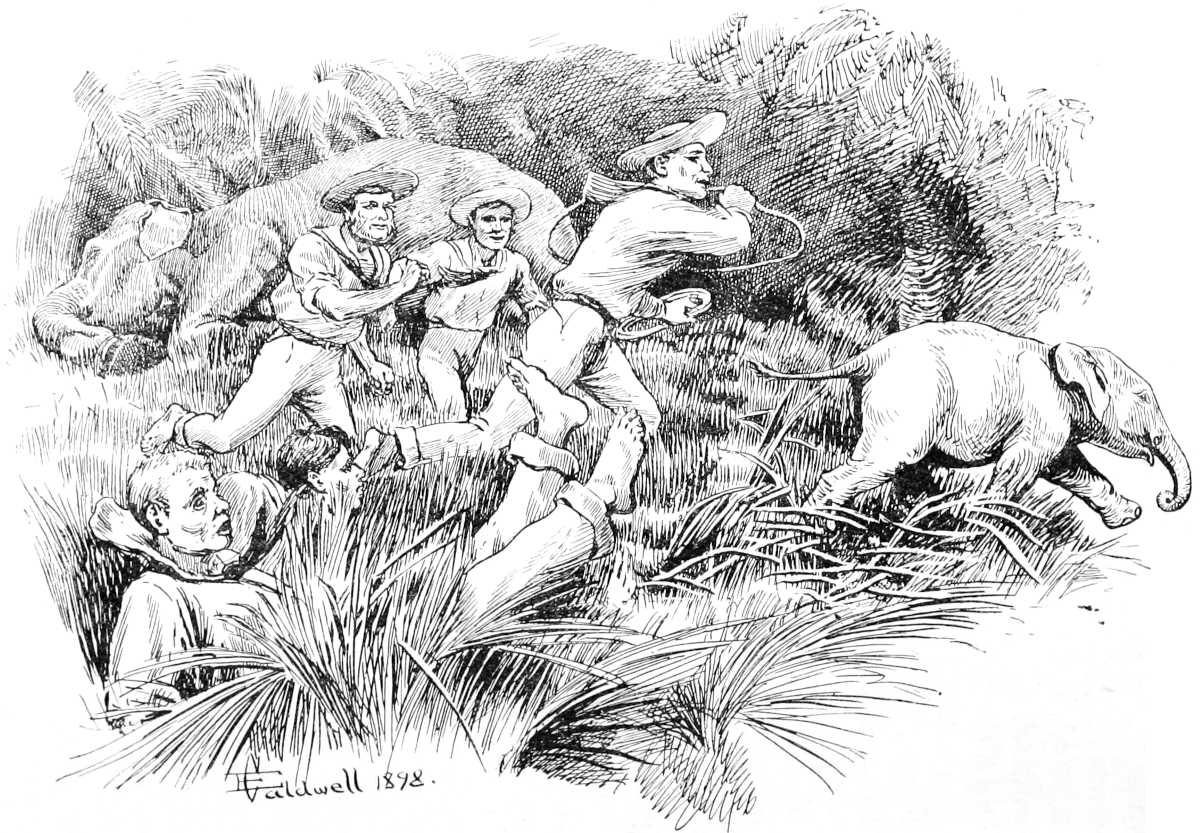

| An Elephant in Chase | E. Caldwell | 131 |

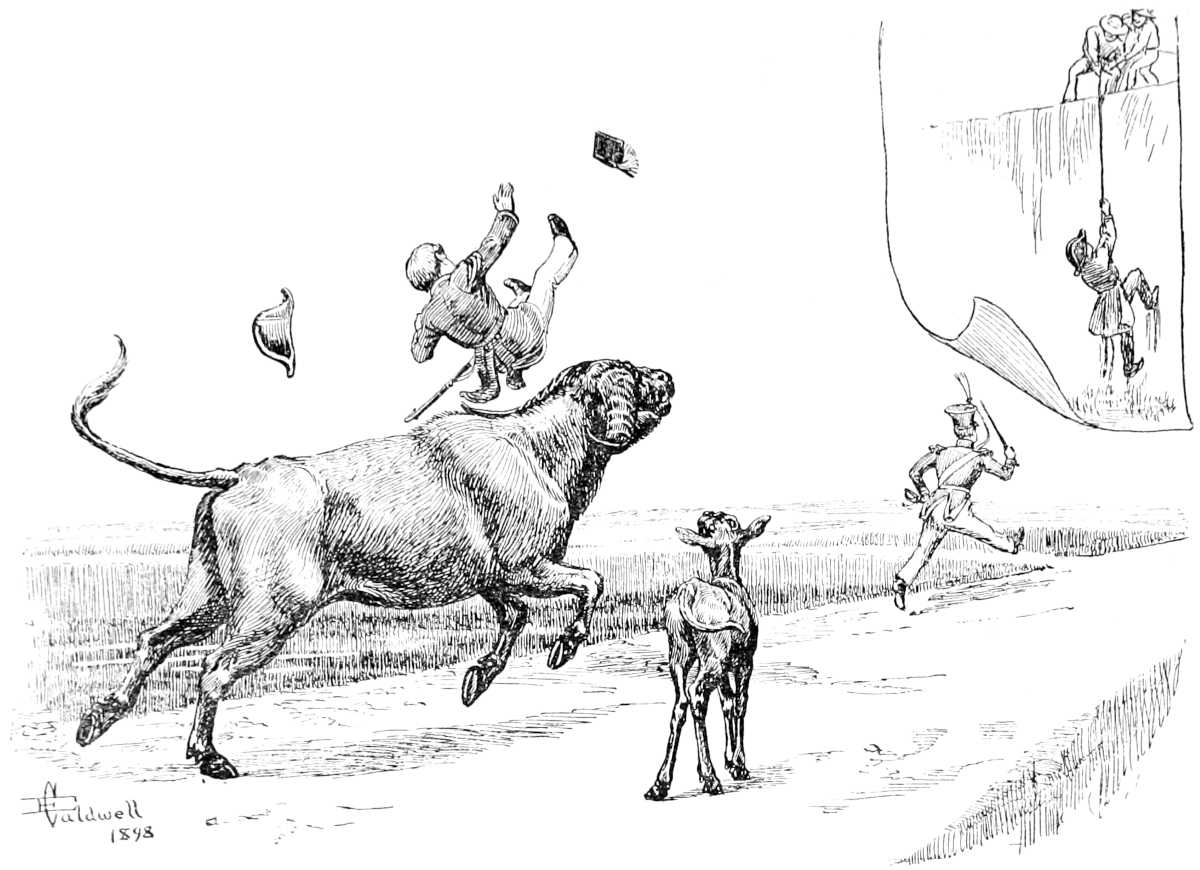

| A Royal Salute | Fred. T. Jane | 138 |

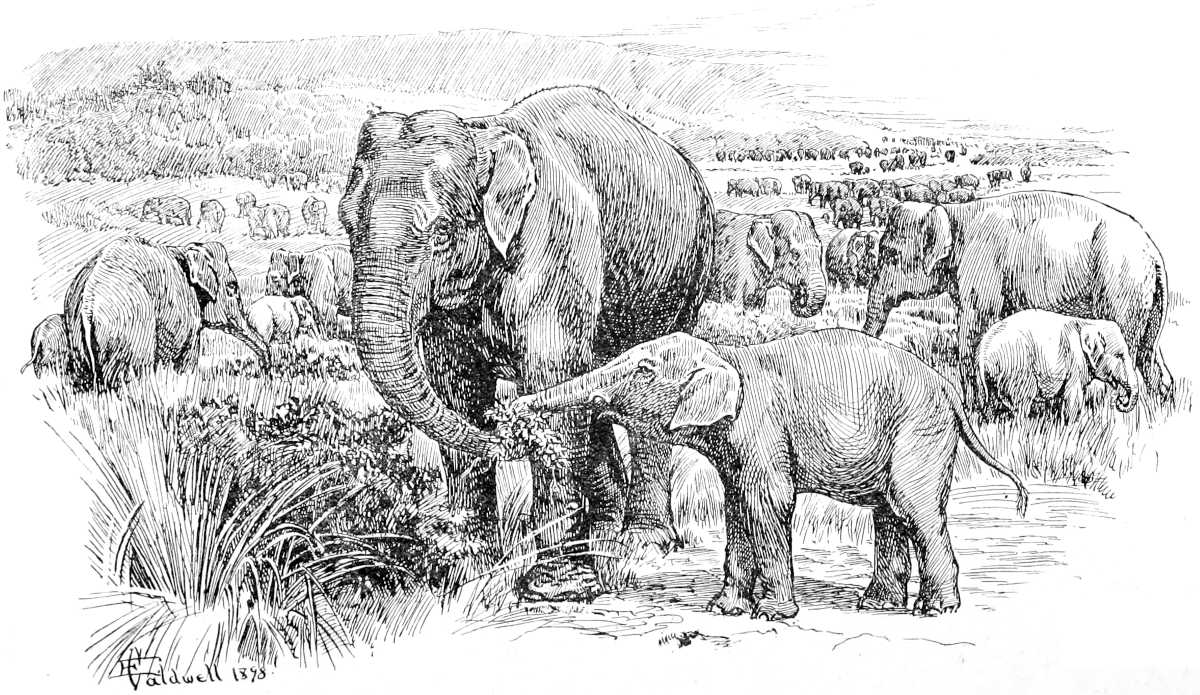

| Elephants with Young at Foot, Moowar Valley | E. Caldwell | 142 |

| Blue-jackets in Chase | ” | 144 |

| Returning from the Funeral | ” | 151 |

| Magicienne at Calcutta | Fred. T. Jane | 154 |

| West African Natives | Anon. | 206 |

| A Factory | Anon. | 213 |

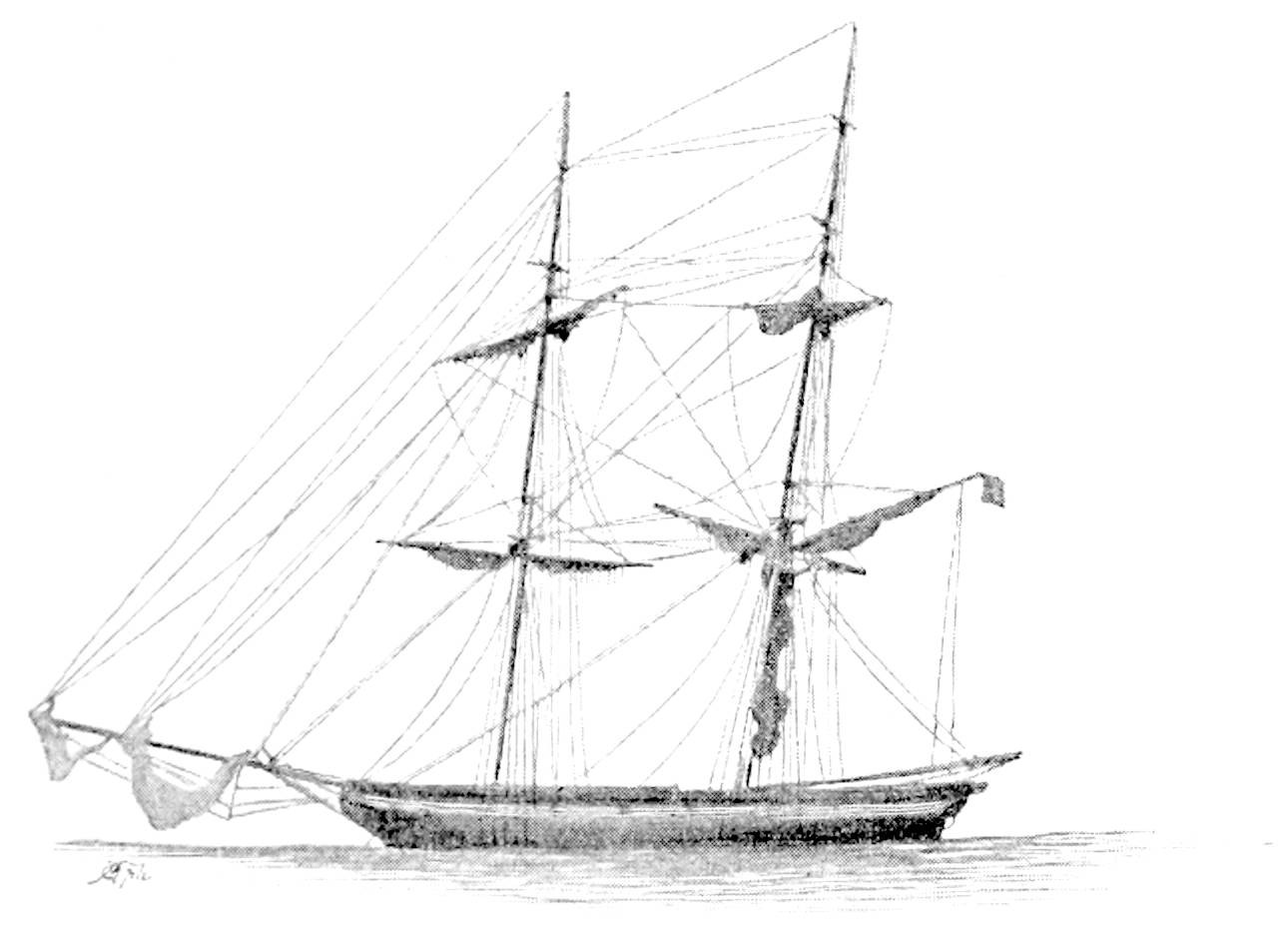

| A Slaver | Anon. | 227 |

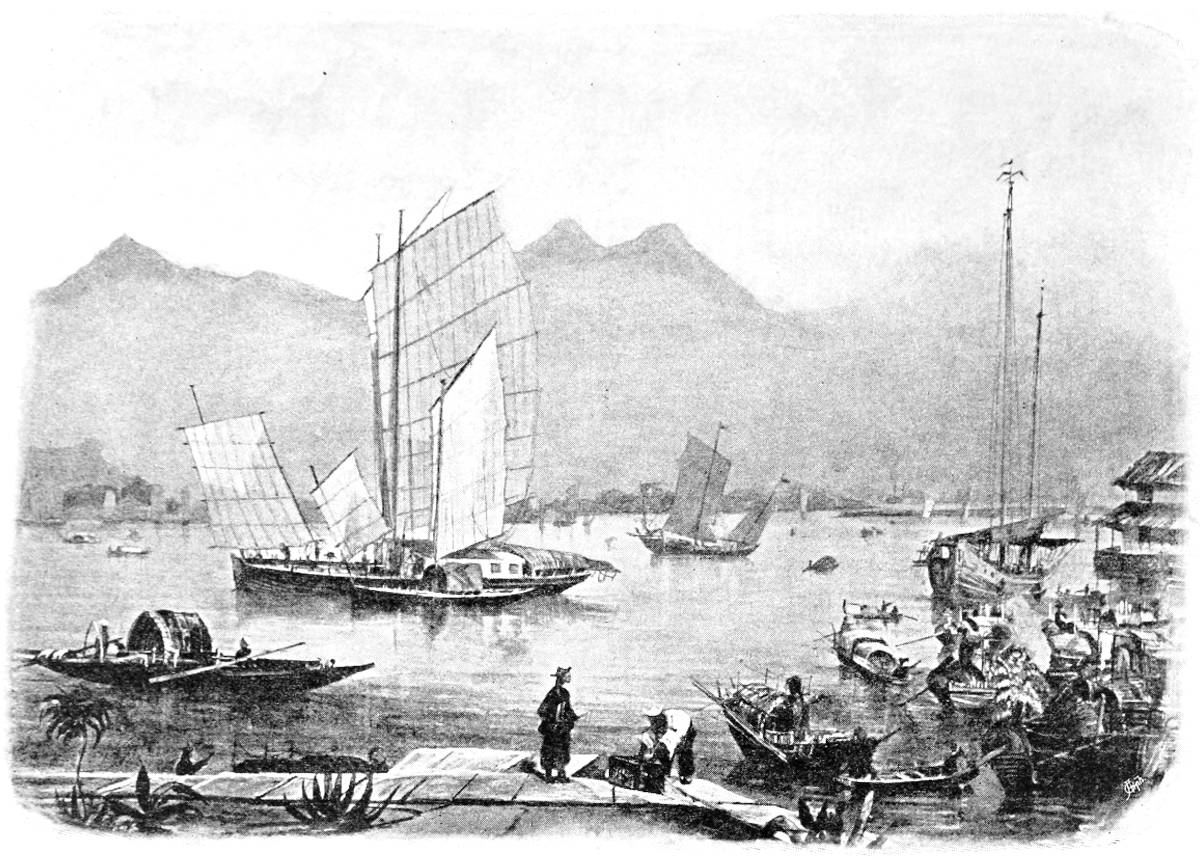

| Hong Kong | Anon. | 265 |

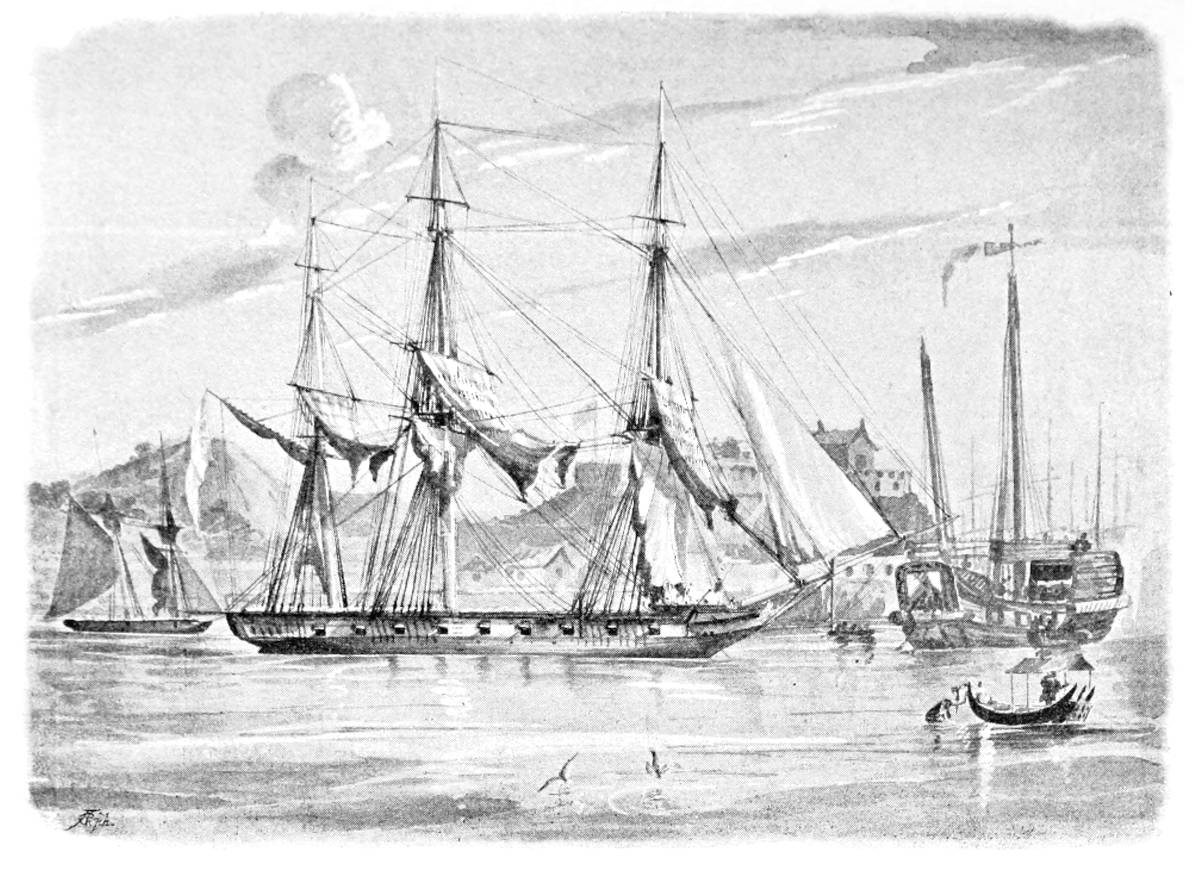

| Dido at Chusan | R. B. Watson | 267 |

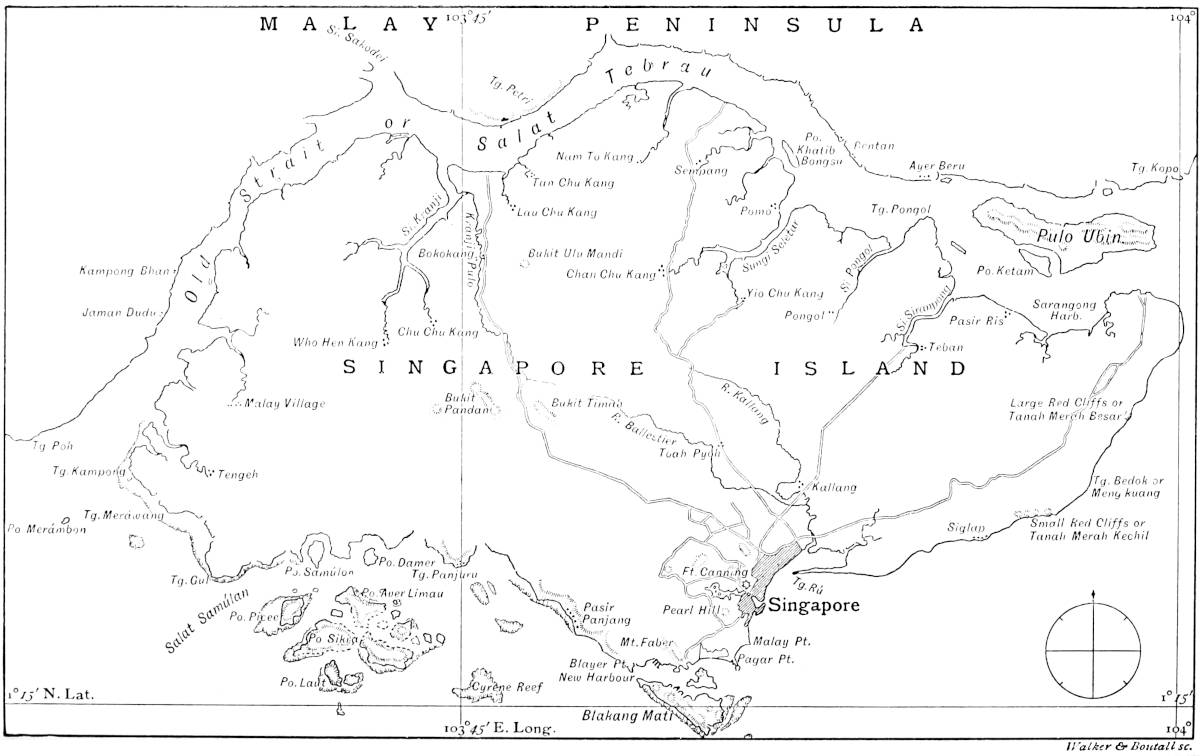

| Map of Malacca Straits and Singapore | 286 | |

| Rajah Brooke | Nina Daly | 289 |

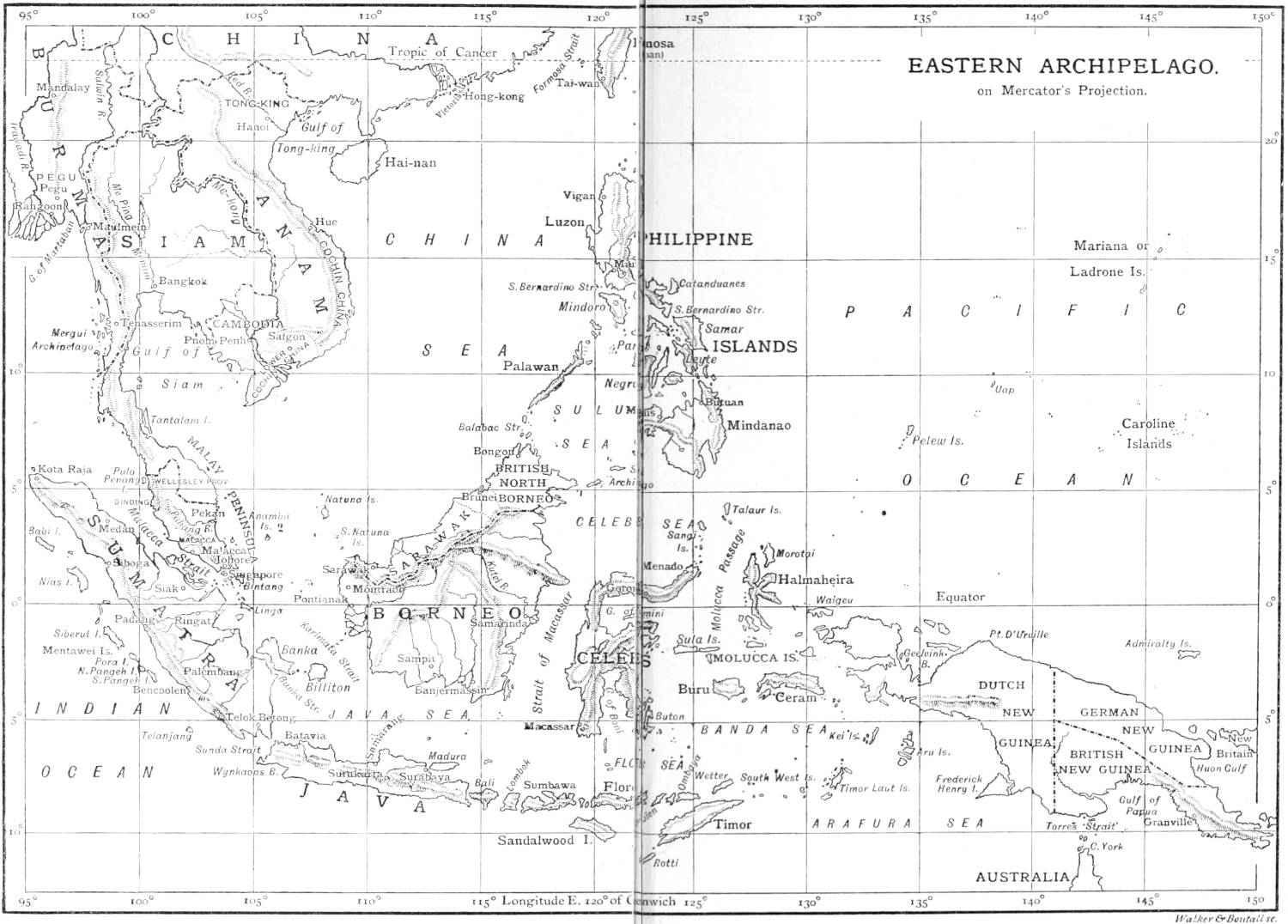

| Map—Eastern Archipelago | 292 | |

| Map of Coast—Borneo | 293 | |

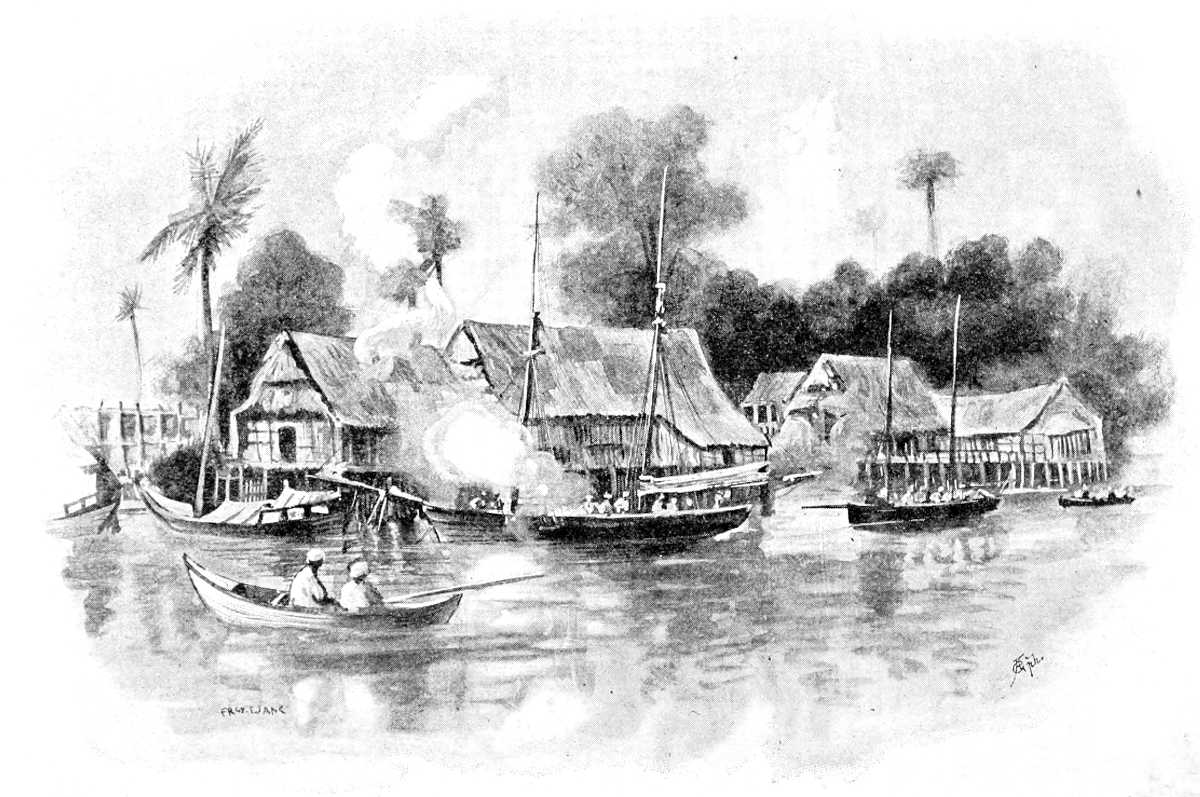

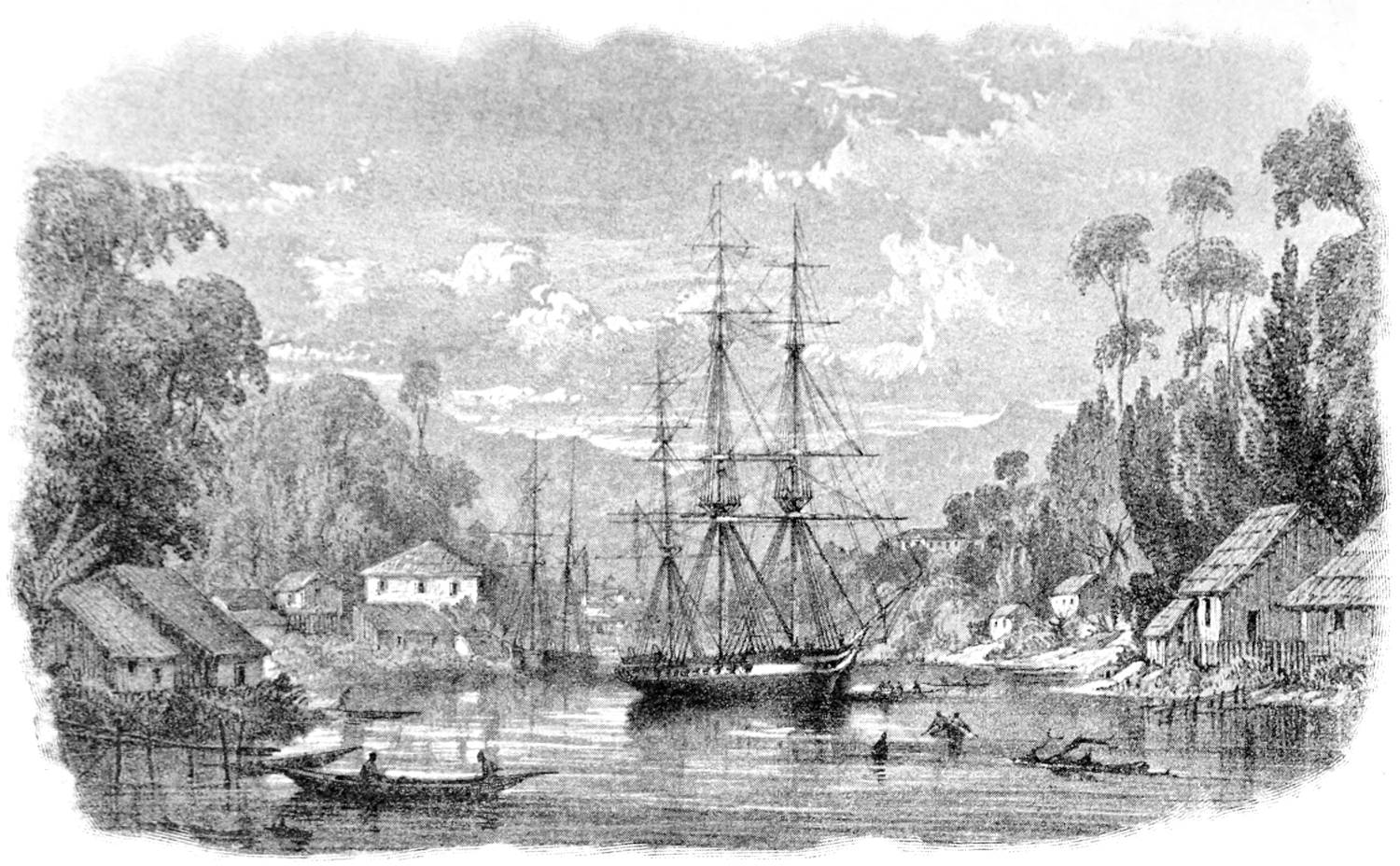

| Dido at Sarawak | Anon. | 303 |

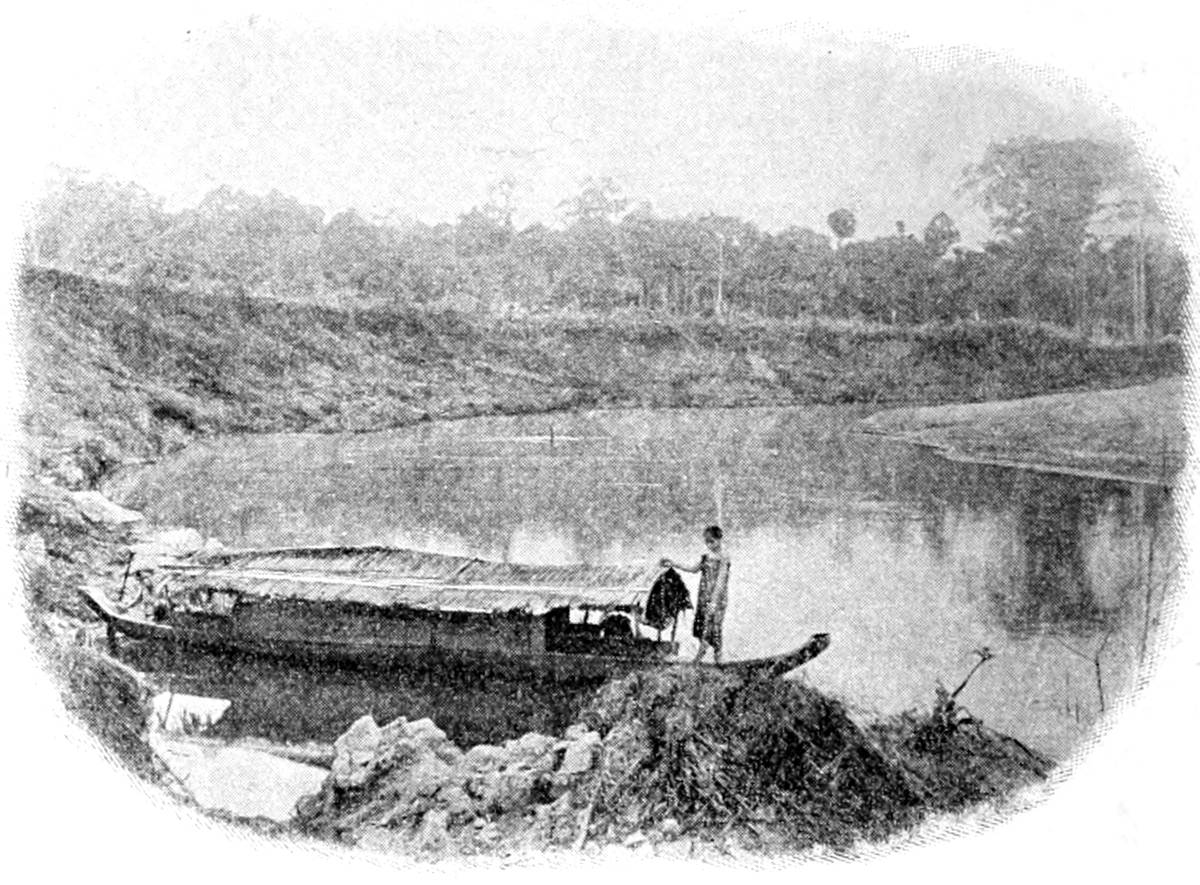

| A River Scene | From photo by Dr. Johnstone | 320 |

[1]

A Sailor’s Life under Four Sovereigns

1809–1822

The baptismal certificate announces my birth at Earl’s Court, Kensington, on June 14, 1809.

It was only in 1820 I learnt from my sister, Mary, that three weeks after birth I was deposited in my father’s footpan to be interred in a garden at the back of the house, not being entitled to a berth in consecrated ground.

That mattered little, as before the final screwing down the old nurse discovered there was life in the “small thing.”

I was christened at Kensington. Henry, Lord Holland, became responsible for my sins, a similar kind act having been conferred by Charles James Fox upon my elder brother; after which I was removed to join the others at Quidenham.

Later on I recollect the nurse trying to frighten us by saying “Boney was coming,” and how glad we children were when we heard of the defeat of that hero at Waterloo; accomplished, as I then believed, by my brother George, an Ensign in the 14th Foot!

My dear mother died at Holkham in 1817.

At the beginning of 1818 my younger brother[2] Tom and I were sent to a school at Needham Market, kept by the Rev. James Wood, a short, muscular man, wearing knee-breeches and powdered hair. A nice wife and children; the latter played with us smaller boys. His brother, a merchant at Lisbon, used to send cases of oranges, which were stowed in the upper shelf of a large cupboard. When in the humour, the master chucked them to us from a ladder singly, giving lessons in catching.

From Portugal we had two schoolfellows, Francisco Nunes Sweezer Vizeu and Alvaro Lopes Pereira. They were kind to me, the smallest boy, and I have never forgotten them.

While there, a young man named Long, who was training for Holy Orders, came occasionally to read with Mr. Wood. He gave me a brass gun mounted on wheels, and a promise of sixpence if I would fire it off during school-time.

At my end of the table I arranged, with books, a screened battery, with the rear open; and then, under pretence of drying my slate at the fire, heated a wire, which was applied according to instructions. The explosion was loud; books flew in all directions; the gun bounded over my head and lost itself behind a row of books, where it remained until next half.

The master tore open his waistcoat to ascertain where he was shot, and then seized his cane; for some minutes I[4] dodged under the table and over the stools, but caught it at last. I was unable to sit, and so went to bed.

My father had in his possession a letter from the Rev. James Wood, stating that I had fired a gun at him, and that “Mr. Thomas” had thrown a slate at his head divested of its frame!

The following half, as the warm weather approached, I succeeded in finding where the master kept his hair-powder, and with it mixed some finely pounded sugar. On coming into school, the flies soon found him, and as he got warm his head became black instead of white. This little game exceeded my expectations, as, irritated beyond endurance, he dismissed us from school. Among our playfellows was a Norfolk neighbour, Edward Gurdon, who sang well and tried to teach me!

Our sister Sophia, who married Sir James Macdonald, lived not far from Needham. They drove over to take us to the launch of a ship at Aldborough. On the return journey, I in the gig, driven by the coachman following the phaeton, ran foul of a fish-cart, and broke the shaft. I was pitched on to the back of the horse, slipped down the trace, and found my way to the phaeton. The coachman had been taking his tea too strong.

At the back of the schoolhouse was a gable-end, up which a pear-tree had long before been trained. The trunk stood some six feet from the wall; a pathway which led to the stables ran parallel, on the outer side of which were pointed rails. On top of these, thin planks placed edgeways, up which jasmine was trained.

One afternoon a ball with which we had been playing lodged in the upper part of the gable-end.[5] I succeeded in reaching the ball, when the branch gave way, and I descended with it in one hand and the ball in the other; the only things that partially checked my fall were the planks. I came down impaled on the spiked rails! A messenger was despatched to Quidenham; but there were plenty of us: nobody came.

We looked forward to our Christmas holidays. My father kept a pack of beagles, much to our delight as well as that of our neighbours, the Surtees and Partridges, both large families and sporting, who, with many others, made our meets very cheery.

Hares there were in plenty. We boys had clever ponies. Mine, Pio Mingo, was peculiar-looking—white, with black spots, bushy mane and tail; showed a good deal of the white of her eye. The like of her might have been found at Astley’s. Both ponies were undeniably clever at finding their way across ditches and through fences, and generally much nearer the hounds than pleased old Capes, the huntsman. Most of the hounds, while running, preferred the furrows to the open plough, as did Mingo, much to the grief of poor little Dancer, Rattler, and others.

But Mingo’s great dislike was a hat, which my elder brothers knew only too well. One Friday morning, after a continued frost, horses and hounds were brought out for an airing, and paraded in front of the house. Fancying that I knew the whereabouts of my brothers, I mounted Mingo in the stable, and was sneaking along so as to get near the protection of led horses.

At that moment, through a villa garden gate, appeared my Waterloo brother. He took off his hat as if to give Mingo a feed of corn. I gripped[6] both mane and crupper, but the rattle of the whip inside the hat was too much. Instead of a somersault in the air, my left foot caught in the stirrup.

Away dashed Mingo, in among the horses, with me in tow. Inside the house old Henley pulled down the window-blinds, that my sisters might not see the expected end. The confusion was great; led horses got loose. I was eventually picked up senseless on a heap of straw and pheasant food under a tree. There was the deep cut of a horse’s tooth across the seat of the saddle—a saddle which had been given my brother George by the Princess Charlotte, and on which we boys had learned to ride.

On the Monday following I was again in the saddle, with a stiffish leg and a few bruises, but none the worse.

Most Norfolk butlers took pride in their breed of game-fowl, and old Henley considered his second to none. The best cocks went periodically to Newmarket,[7] their performances watched with interest only inferior to that of the race-horses. Carrier-pigeons, too, he bred. On one occasion the birds, hatched from eggs brought from Newmarket, found their way back as soon as able to fly—not more curious than a dog carried in a hamper from Sussex to Scotland finding its way back to Goodwood in a couple of days!

Kenninghall Fair was an event for us children. Admiral Lukin, from Felbrig Hall, visited Quidenham at that time. He played the flute. The march across the park with drums and fifes was imposing. Not far from Felbrig we had another home at Lexham Hall, belonging to the Walpole-Keppels. The whole county appeared to work together except at election time, when Wodehouse opposed Coke.

About this time my brother Tom and I were summoned to our father’s dressing-room, when he informed us that it was time we selected a profession. We both decided for the Navy. Father thought we should have separate professions. As we disagreed, I hit Tom in the eye, which he, being biggest, returned with interest. When we had had enough, father decided we should both be sailors.

Similar politics, somewhat Radical, had years ago brought the families of Coke and Keppel together, and we looked forward with pleasure to our periodical visits to Holkham. Mr. Coke had four daughters. The eldest died before my time; three had married peers—Andover, Rosebery, and Anson. Lady Andover, who was early a widow, married secondly, the good-looking and distinguished Captain Digby, who commanded the Africa at Trafalgar. Lady Anson had two handsome sons; one we called Tom, who afterwards became Lord Lichfield. He was descended from Lord Anson who commanded the Centurion and[8] sailed round the world. On board was Augustus Keppel, a midshipman, afterwards Lord Keppel.

There was a younger son, William, in the Navy, whom I met later. Eliza Anson became Lady Waterpark, and her sister Frederica married the Earl of Wemyss and March. Mr. Coke had a younger daughter, Elizabeth; she likewise was charming, and managed the domestic part of the house. In 1822 she married Mr. Spencer Stanhope.

Among Mr. Coke’s intimate friends was Sir Francis Burdett; in fact, Holkham was the centre of the leading Whigs of the day. Sir Francis had been liberated from prison, where he had been confined for exciting a mob, as well as for writing a pamphlet on the trial of Queen Caroline, on the strength of which a party assembled to meet him at Holkham.

After a sojourn there it was arranged that the party should adjourn to Quidenham. There was great excitement throughout the country about the trial.

[9]

Being short I was told off to go with Sir Francis, so as not to obstruct the view of the hero. The travelling carriages of those days were light; no box or driving-seat, splashboard only, the body hung on C-springs; four horses and postboys.

At Fakenham the populace were prepared; horses were taken off, and Sir Francis was, much to my delight, drawn through the river. The same fun was repeated at Dereham, where we met the Duke of Sussex, changing four posters at the King’s Arms, His Royal Highness likewise on his way to Quidenham. We also stopped for refreshments. Outside the inn was great cheering, and cries for “the Queen and her rights.”

After a short stay at Quidenham the party broke up, and I saw Sir Francis start on a ride to London, calling at Euston, a journey of nearly a hundred miles.

[10]

[11]

I was much with H.R.H. the Duke of Sussex, going from one country-house to another in his travelling coach, which held an enormous amount of luggage. Both footmen were armed; it was no uncommon thing for luggage to be cut from the back of a travelling carriage in the vicinity of London. Royalty paying no ’pikes, with four post-horses, and boys in condition, we got rapidly along.

Newstead Abbey was the object of our journey. It belonged to His Royal Highness’s equerry, Colonel Wildman, a dapper little Hussar, who had served through the Peninsular War, and had recently bought the place of Lord Byron. The workmen were still engaged in restoring the beautiful Gothic building, on which the Colonel was expending £200,000. The work was being done with taste and care; none of the traits of its former owner had been obliterated. Side by side with the arms of Lord Byron were carved the heraldic device of the Wildman family. Indeed, it was a source of consolation to Lord Byron that the one spot in England dear to him had fallen into the hands of his old friend and schoolfellow.

The famous drinking-cup, which Byron made out of a skull found in the Abbey cloister, was mounted on a gold stand, with the famous lines engraved; and, in accordance with the tradition of the house, when a visitor arrived, a bottle of wine was poured into the skull, which the guest was expected to empty.

While we were there, Mr. (afterwards Lord) Brougham arrived from an election tour. I saw him empty his share of the claret at one draught, and he was unusually pleasant afterwards. His younger brother, father of the present Lord, was staying in the house at the time.

On returning to Holkham, I found the school-room[12] was nearly full. Not that we boys were always admitted. There were Miss Digby—so beautiful!—and two Ansons—such dear and pretty children! Admiral Digby had two sons; Edward was of the same age as myself, and we established a friendship which lasted his life. He had a younger brother, Kenelm, likewise a good fellow, thinking of the Church.

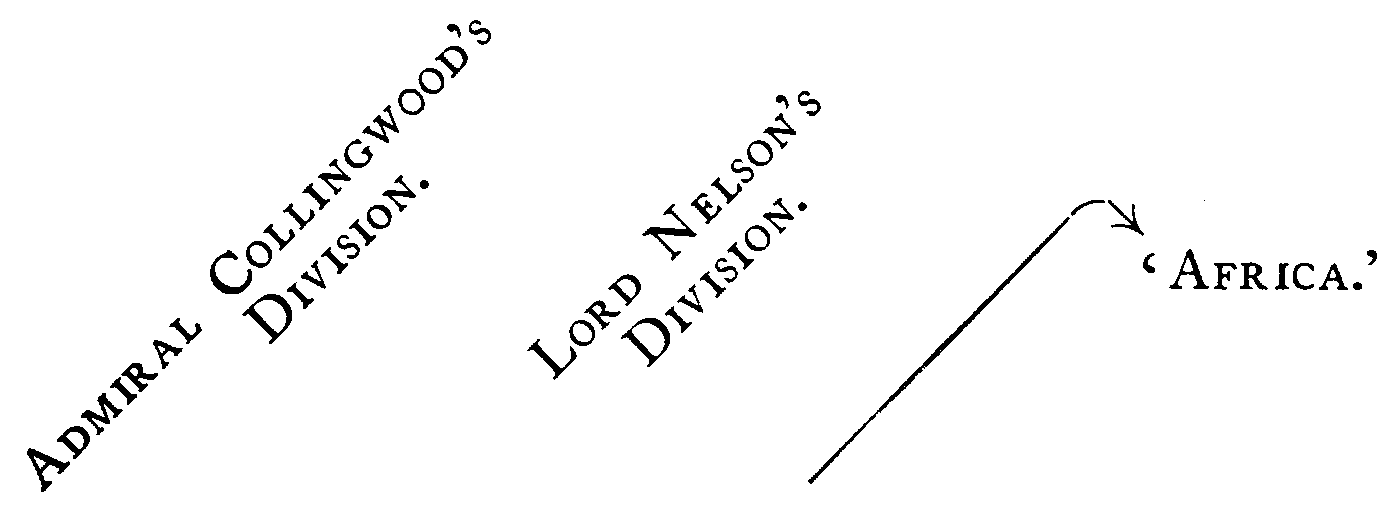

It is not my intention to attempt the biographies of many of the fine fellows whose path I crossed, but since I commenced these souvenirs I have had the opportunity of inspecting letters that might never have seen daylight had I not inquired of Lord Digby, son of my lamented friend, the number of guns his grandfather’s ship carried at Trafalgar. The search produced the original letter, written by then Captain Digby to his uncle, Admiral Hon. R. Digby, of Minterne, Dorset:

[Copy]

“‘Africa,’ at Sea, Off the Straits,

November 1, 1805.

My dear Uncle,

I write merely to say I am well, after having been closely engaged for six hours on the 21st of October. For details, being busy to the greatest degree, I have lost all my masts in consequence of the action, and my ship is otherwise cut to pieces, but sound in bottom. My killed and wounded 63, and many of the latter I shall lose if I do not get into port. Out of so many great prizes, it has pleased God that the elements should destroy most, perhaps to lessen the vanity of man after so great a victory.

[13]

I will give you a rough sketch of the lines going into action; more minute it shall be hereafter.

I beg my love to Mrs. Digby, and remain,

Your affectionate nephew,

(Signed) H. Digby.

French Line on Larboard Tack.

(To which was added the following postscript):

I really have no time to say more, surrounded as I am by the wounded men in my cabin, and in all sorts of employ, completing jury masts, etc., etc., and I will thank you to say so to Dr. Shiff and my brothers and sisters.

The Africa was, with many others, dispersed by variable winds, and perceiving the French signals during the night, I took a station at discretion, and was the means of being early in action the next day, engaging the van as I ran along to join the English Lines.

After passing through the line, in which position I brought down the foremast of the Santissima Trinidada, mounting 140 guns; after which I engaged, within pistol-shot, L’Intrépide, 74, which afterwards struck and was burnt, Orion and Conqueror coming up.

A little boy that stayed with me is safe. Twice[14] on the poop was I left alone, all being killed or wounded. I am very deaf, with a sad pressure over my breast.”

I have not space to describe half the services of the gallant Digby. In 1796 he was posted into the Aurora frigate, and in less than two years had captured six French privateers, one lettre de marque, and one corvette, L’Égalité, making a total of 124 guns and 744 men, besides forty-eight merchant ships taken or sunk. In command of the Leviathan, with Commodore Duckworth, he assisted in the capture of the island of Minorca. In command of the Alcmene, he captured two French men-of-war, Le Dépit, 3 guns, and La Courageuse, 30 guns and 270 men; also on October 17, 1799, two Spanish frigates, Thetis and Brigide, each of 32 guns and 300 men. They contained 3,000,000 dollars, and it took fifty military waggons to convey the specie from Plymouth Dock to the citadel. His prize-money, as stated by himself, amounted to £57,300 before he was thirty years of age, with £6300 more before he was thirty-six.

I read that in the beginning of 1818 the following Whigs dined together in compliment to Mr. Coke, at Wyndham, near Quidenham: The Rev. R. Coleman, in the chair; Bathurst, Bishop of Norwich, Lord Albemarle, Sir Francis Burdett, Mr. R. Hammond, Lord Cochrane, Sir Thomas Beevor, Mr. Gurney, Sir Jacob Astley, Mr. Lerwlie, and Admiral Lukin, at that date rather Liberal.

A tutor from Wells was found to coach me for the Royal Naval College. One morning, after breakfast, Mr. Coke told me to join him in his study, directing me to sit on a certain chair, he at[15] his desk. After a while he called me, and said: “Now I will tell you why I put you in that chair. Young Nelson sat there on an occasion when he came to make his declaration for half-pay as Commander.” Nelson’s home was with his father, the clergyman at Burnham Thorpe, about three miles from Holkham. Mr. Coke likewise introduced young Hoste (a neighbour) to Nelson.[1] At Holkham now there is a bedroom called “Nelson’s.”

Early in 1822 I was sent to my relative, William Garnier, Prebendary of Winchester Cathedral, whose home was in the Close; but it was his brother, the Dean, better known to us as “Uncle Tom,” to[16] whom I was consigned. He had a son, George, who was already at the Royal Naval College.

It was on February 8 that I started with Uncle Tom in the Prebendary’s family coach, drawn by four fat greys, coachman on box, boy on near leader, pace about five miles per hour, for Gosport. On arrival I saw, for the first time, among other vessels, three full-rigged ships of the line, whose trucks reached at least 220 feet above the water-line. As yet I had seen nothing larger than a collier brig alongside Wells Pier.

Uncle Tom took me in a wherry across the harbour to the dockyard, and so to the Royal Naval College, where I soon found myself in the presence of the Governor, Captain Loring, a warrior in uniform; as imposing to me as the leviathans I had just seen. Professor Inman was there—a tall man in black, with an austere countenance; but there was that in him that I liked. How I got through the examination I forget, but that day found me an officer in the service of King George IV.

Captain John Wentworth Loring was the son of Joshua Loring, who held a staff appointment at Boston. At the end of the war he settled in Berkshire. His son, born in 1785, entered the navy as midshipman on board the Salisbury in 1819. While Loring was serving in the West Indies in command of the Lark sloop, she capsized in a hurricane. They cleverly saved themselves by cutting away masts and rigging, and, being well battened down, the vessel righted. She was towed into port at San Domingo to refit. Loring gained so much credit for the expeditious manner in which he performed this duty that the Admiral, Lord Hugh Seymour, appointed him Acting Captain of[17] the Syren, 32-gun frigate, which had lately come out from Bantry Bay in a thoroughly demoralised and mutinous state!

While cruising off Cape François the crew refused to work, and a plan got wind of their intention to secure their new Captain and officers, and join the pirates, who were then to be found in most parts of the West Indies. Loring, with his officers, took possession of the after part of the ship; the wind being in the right direction, they steered for port. They were three days without change of raiment. On joining the Commander-in-Chief, Sir John Duckworth, who had succeeded Lord Hugh Seymour, the mutineers were tried by court-martial, and six of them hanged at the foreyard arm. Through the intercession of Loring, one of them escaped capital punishment.

On November 4, 1819, Captain Loring was appointed Governor of the Royal Naval College. He was for forty-four years on the active list, and of that time only four unemployed. In July he was made K.C.B., having previously been knighted by King William IV. His uniform was: blue coat, open in front, gold epaulettes, white kerseymere waistcoat, pantaloons to match, with Hessian boots, straight, thin sword, and cocked hat.

Rouse was the Senior Lieutenant. This gallant old officer lost his leg in the attack upon Prota in February, 1807, when serving under Sir John Thomas Duckworth, and in consequence of his wound was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant. When the wooden leg broke, he was allowed to draw another from the dockyard joiner’s shop.

Malone, the Second Lieutenant, was a good-natured Irishman, and kind to me because his wife[19] was a Norfolk woman. There were two artillery drill-sergeants and three first-rate warrant officers, a gunner, boatswain, and carpenter, who took us round the yard in batches out of school hours, and of whom some of us learned more than we did inside. They illustrated in the dockyard what we had found difficult, with no object to refer to.

There were two fine twelve-oared cutters, which the lieutenants managed. We learned to pull as well as to steer under sail. We had, in addition to school, French, drawing, and dancing masters, also fencing. The French master was, I believe, an émigré, a Marquis de la Fort; but of all, I think we liked Schetkey, the drawing-master, best.

Two old women used to bring baskets of grub—tarts, fruit, etc. Towards the end of the half they gave “tick” to those whom they knew would return.

Under the care of my good-natured kinsman, George Garnier, I got on very well. He, however, left the end of the half, and joined the Delight brig, in which he afterwards sailed from the Cape of Good Hope, and was never again heard of.

Our uniform was a blue tail-coat, stand-up collar, plain raised gilt buttons, round hat, gold-lace loop with cockade, and shoes. We cadets had each a cabin about seven feet square, with a window, except the corner ones, which at the monthly changes were occupied by those who had been oftenest on the black-list, and did not require daylight.

There was an occasional launch from the dockyard; one of them was the Tweed, of 28 guns, a new form not much thought of, and called donkey-frigates. Subsequently she was christened by Miss Loring, and to this vessel I was appointed on leaving the College.

[20]

We had a nice set of fellows. Some of them sons of distinguished officers, among them Suckling, Pasco, Hallowell, Blackwood. On muster or parade we were in subdivisions or companies; the best-behaved had charge each of one of these, and wore a midshipman’s white patch instead of a bit of braid on the collar.

The boy I looked up to was William Edmonston; he was clever, and passed out with a first mathematical prize medal (before completing his two years) as a midshipman in the Sybille, 42, Captain S. Pechell. He was wounded in the face in a boat action against pirates near Candia. Edmonston had the best sort of courage—brave without being rash. He got into Parliament, but I, having been kept at sea, got ahead of him.

George King entered the College the same day as myself, and we kept working together, although in different ships, for many years.

We cadets were not allowed outside the dockyard; the stage-coaches that took us away were obliged to come inside the gates. We were but boys, and provided ourselves with such missiles for mischief as we could find in the yard—iron ringbolts, for example, which were dangerous if thrown with precision.

Before the half was up, we drew lots for the much-coveted box-seat; that on His Majesty’s mail on one occasion fell to me. There were several night-coaches, but the “Nelson,” the only “six inside heavy,” was the favourite. It carried thirteen passengers, and stopped to refresh at Liphook. The food was bespoke a week before: in winter beefsteaks, onions, and plum-pudding, but in summer a goose, ducks and green peas, with onions to any[22] extent. It often happened that the coach left a passenger or two asleep on the rug.

Outside the gates there was no difficulty in obtaining pea-shooters and other small means of annoyance. On the night when I had the box-seat, the Royal Mail picked up and dropped boys as we came, so that it was midnight before we reached Godalming. The postmaster having turned in, the Mail pulled up as usual under his bedroom windows. The moment they were opened, the postmaster and his wife were assailed with pea-shooters and other missiles. The guard was saying “All right,” when the postmistress, calling “There is something else,” emptied the slops on the boys as the Mail drove off; I, having the box-seat, escaped the odoriferous bath.

That gallant officer, Sir William Hoste, who commanded the Albion, one of the harbour guard-ships, used to visit us during play-hours and tip the Norfolk boys with a half-guinea each, although himself a poor man. We were proud at being noticed by the gallant Hoste, who commanded at the finest frigate action off Lissa, with such men as James Gordon Phipps Hornby, Whitby, and others with whom I subsequently became intimately acquainted. There was also a young fellow, Lieutenant the Hon. William Anson, belonging to the Tribune, 42-gun frigate, who used to come and see me and chat about Holkham. Adjoining the Naval College was the house of the President-Commissioner, Captain Hon. Sir George Grey, brother of the Premier.

His nephew George and I became great friends: he joined the service, but not through the College.

While at the College we had repeated visits from those who had previously left, and who put us up to the orgies that went on in the hulks alongside the[24] ships to which they belonged. I did not fail to remember this when my turn came.

My brother Tom joined on December 5, so that when we returned in January, 1824, from the Christmas holidays, we had only been two months together.

Among the friends I made at College were Hallowell, Suckling, Francis Blackwood, all more or less connected with Nelson.

I went up with others for examination, but failed to get full numbers on account of having in my possession a penny handkerchief, given me by one of my late playfellows, on which was printed an outline of a map of the coast of England. Now, the geographical master, who was short-sighted, always read with his nose close to the paper. Through a sheet of foolscap he had pierced a hole with a pin, and before I could blow my nose he was down on[25] me like a hawk. The consequence was that on February 7, 1824, I was appointed to His Majesty’s ship Tweed, Captain F. Hunn, half-brother to Mr. Canning, with one year ten months two weeks and two days’ time, instead of two complete years of service.

Uncle Tom Garnier kindly undertook to give directions for my outfit, and for a while my valuable services were dispensed with.

[26]

The Tweed, 1824

Having paid many parting visits, I returned to Portsmouth, and, dismounting from the “Regulator” coach, went straight to the outfitters’ and was soon in uniform. What I thought most of was a small dirk suspended from my waist. Having viewed myself in various positions, I sallied forth.

From mids who revisited the College I learnt the sort of fun that went on in the refitting hulks. I was not so green as I looked. Instead of reporting myself on board the Topaze, I ascertained that Captain Hunn lived with wife and family at No. 15 Jubilee Terrace, Southsea. The time being that when he would be going to dinner, although dusk, I took up a position on the south side of the sallyport bridge.

Presently I saw a blue boat-cloak, surmounted by a gold-laced cocked hat, and a sword protruding. I stepped on one side and saluted.

“Who are you, youngster? and what’s your name?”

I soon squeaked out that I belonged to His Majesty’s ship Tweed, just returned from leave, and was going to report myself. Name Keppel.

“Come along with me.”

[27]

I was shortly ushered out of the cold into the presence of Mrs. Hunn and two charming young ladies in a warm drawing-room, and dinner ready. Never was such good fortune! Never was I so hungry!

The coxswain was sent for my clothes, a bed made up on the sofa. The next day I was installed “gig’s midshipman.” Rather a good beginning, which I fully appreciated.

I did not trouble myself about the fitting out. Just before starting we were supplied with a proportion of smugglers, whose penalty for defrauding His Majesty was to serve before the mast on board a man-of-war. They were equal to our best seamen.

We sailed from Portsmouth on April 12, Mrs. Hunn and my playfellows with us. We saluted the flag of our Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Sir James Hawkins Whitshed, and anchored at Spithead, which we left on 18th, anchoring successively at Cowes, Yarmouth Roads, and Plymouth Sound, saluting the flag of the Hon. A. J. Cochrane.

[28]

Among the frequent anchorings and departures I learnt some of the various duties expected of officers of my particular rank. One of these was to hold a dip in the tier while the great hempen cable attached to the anchor was being hove in, and stowed by quartermasters below the reach of daylight. It was a neat piece of seamanship, on which the best and the least experienced of petty officers were employed. The tier was a large oblong space. The end of the working cable was secured in the bottom of the ship, frequently round the heel of the mainmast. To heave in the cable with anchor attached required a “messenger” without an end. This was a small cable of proper proportions passed round the capstan and forebits, so that one side ran parallel to the cable, to which it was secured by nippers that held it until near the hatchway above the cable tier.

As the nippers were taken off, boys were stationed to carry them forward to be reapplied; the capstan bars were manned by marines and seamen not stationed aloft. We youngsters had to hold the dips to enable the petty officers to see that each bend was closely packed, the centre, where they worked, being clear. The coil in the tier not exceeding three or four feet, according to size and space, we had to jump smartly with our dips on the words, “Side out for a bend.” The expression was used long after chain cables were introduced. “Purser’s dip” was a strip of cotton soaked in tallow until it grew into a young candle.

Bumboats were the delight of us youngsters. If one wanted to enjoy a pot of clotted cream, the best way was to carry it aloft, taking a foot of pigtail to propitiate the captain of the top.

We left Plymouth on May 2, and following day came to in Carrick Roads at Falmouth. Mails to[29] most parts of the world were carried from here in men-of-war, chiefly brigs, commanded by senior lieutenants, and a few by distinguished old warrant officers.

There were thirty-six of these vessels, some with high-sounding names, such as Prince Regent, Duke of Marlborough as well as of York, two Dukes of Kent, Ladies Wellington, Queensberry, Mary Pelham, etc. They were all in first-rate order.

In the important town of Falmouth the Commanders had a society peculiarly their own, ladies taking precedence according to the seniority of their husbands on the Navy List—luckily, not that of the names of the ships their husbands commanded. Of course, there was no quarrelling among the grass-widows. We were here four days.

Arrived in the magnificent Cork Harbour, we saluted the flag of Rear-Admiral of the White, the Right Hon. Lord Colville, Commander-in-Chief of His Majesty’s ships in Ireland. There was a great deal of smuggling all round the coast, and some of our smartest cruisers employed. Among the most fortunate was the Gannet, 18; she went by the name of the “Golden” Gannet.

The Admiral was tall and imposing-looking; as gig’s midshipman I had many opportunities of seeing him. He paid almost daily state visits from his residence in the Cove of Cork to the dockyard on Haulbowline Island, dressed in full uniform. He wore his cocked hat athwartships, gold epaulettes, white pantaloons and Hessian boots. On his stepping into the state barge, the coxswain, standing up behind him, piped the time for each solemn stroke of the oars; the yards of the flagship were manned, while the marines, ranged across the poop, presented arms.[30] The distance was short, but I thought the ceremony grand.

Semiramis was an old 42-gun frigate. Being light, and floating high out of the water, she was painted with two tiers of ports, and had the appearance of a ship of the line suitable to the flag she had to carry. No merchant ship trading between Cork or any port would attempt to pass without lowering her upper sails.

Before leaving, the Pylades, 18, Commander Fead, arrived with a smuggling lugger, a beautiful vessel with a crew of over fifty fine-looking men. The Commander-in-Chief while on the station made nearly £9000 prize-money, his share being one-eighth, after expenses paid. Mr. Dunsterville had charge of Haulbowline, with a charming wife and family. A nice boy joined us as mid, deliciously Irish. With them I made excursions to Cork, and I enjoyed a lunch at the same time at the mess of the 13th Hussars.

We sailed from Cork on the 25th, and got into the wide and open sea, when I saw, for the first time, the horizon of blue water all round. I now came in contact with those who were my messmates, among them a number of masters’ mates, whom the Admiralty did not promote, but gave them the option of serving on.[2] The duties of these elderly gentlemen were mostly nominal; they were styled mates of the hold or of stores, etc. They seldom appeared on deck except on Sundays, when they took their week’s exercise. Their uniform was a blue coat, in shape like our now plain evening-dress, anchor buttons and a small white cord edging, white pantaloons, Hessian boots, cocked hat, and sword.

[31]

[32]

It was considered a compliment to be spoken to by them. I was favoured by being asked if I had not come to sea to avenge the death of Nelson. Others were anxious to know if my mother cried when I left home. Down in the midshipmen’s berth they reigned supreme; spoke very little before grog-time; then a fork was stuck in the beam, a signal for us youngsters to scuttle out as fast as we could.

A servant was told off to look after me. I forgot his name, and asked one of my aged shipmates; word was passed along the lower deck for “Cheeks,” the marine.

There was no place for midshipmen’s stores, except the lockers on which we sat. Each of us was supposed to bring two table-cloths; one lasted a week, when the steward—his name Edward Low, but called “Tommie Plenty”—took possession of it to wipe knives, forks, cups, and spoons. It smelt before the next was due. We had no candlesticks. Dips obtained from the purser were stuck in bottles supported by forks fixed where the planks of the table had shrunk. One morning, when “Tommie” was holystoning under the table, the point of a fork lifted his scalp. While he was on the sick-list we youngsters had to do cooking, etc.

I often confirmed Marryat’s story of the mid running along the main-deck with a tureen of pea-soup, calling “Scaldings!” to clear the way.

One of our old mates had served in a fast-cruising frigate, when, owing to the number of prizes taken, officers being sent away in charge, the duties fell heavily on those remaining. Our messmate had to keep watch and watch. At last his turn came. On taking charge of the prize, the frigate having made sail, he sent for the petty officer, a gunner in charge[33] of the prize crew, and told him to steer north-east and call him in three weeks.

On June 5 we arrived at Madeira, at which enjoyable place we remained eight days. Here our Captain, his wife, children, and gig’s midshipman were entertained by the kindest of merchants, Mr. and Mrs. Bean, as well as by Mr. Gordon, a partner. Markets were full of fruits of all sorts—oranges, mountain strawberries, grapes, and bananas; ponies, donkeys, picnics, etc.; who would not be a midshipman? We appeared to be welcome everywhere. The troops and music I enjoyed, but, what appeared curious—drill orders to the soldiers were given in English—remnants of Peninsular!

Our next stopping-place was St. Jago, one of the Cape de Verds. It was dull after bright Madeira. Markets were full of tropical fruits, monkeys, parrots, yams, and other vegetables, ground-nuts, etc. We remained one whole day.

Of my next visit I retain some painful remembrances, but enough for the day is the evil thereof.

We were now far within the tropics—flying-fish, porpoises, dolphin seldom out of sight; besides, I thought of that terrible “Line” of which I had heard so much.

At 8 P.M. a light ahead was reported. We hove to. The sea-god Neptune came over the bows and reported to our captain his intention of paying a visit of welcome to all those who had not previously come within the tropics. He brought with him his secretaries, who inscribed the names of all first visitors. One old marine got off by stating he had served in the Peninsula!

Soon after I observed a lighted tar-cask floating astern, and hoped that “His Majesty” was burning[34] in it. The next morning he boarded and took possession, and found plenty of brutal followers to help him and all concerned in his disagreeable duties.

I was seized by one of his greasy constables and conducted I knew not where, and seated on something which felt like a capstan-bar. My face was plastered with a mixture of tar and dirt, and scraped off with a jagged piece of iron representing a razor; then, tipped backwards into what I thought was overboard, I felt myself in the grip of other brutes representing Neptune’s bears, who held me till I had swallowed a sufficient portion of the filthy bath. I was then free for life to join any future orgie.

The ducking-pond was formed by a sail secured at the corners to the combings, the centre lowered on to the main-deck, and filled from the wash-deck pump. On the stern of one of the boom-boats, overlooking the proceedings, was Neptune with Amphitrite by his side, on whose knee sat a promising young cub, son of the sail-maker; allowed on board by special permission before leaving England, apparently looking forward to superintending similar operations. I found my way into the Captain’s after-cabin, where my playfellows gave me a biscuit with jam and a little something to wash it down.

We made Cape Frio July 17: then, squalls for a couple of days. Two days after we made our number to the Spartiate bearing the flag of Rear-Admiral Sir George Eyre. The atmosphere was so clear that we could distinctly make out the affirmative when the head of the topgallant sails only could be seen above the horizon—a distance of fifteen miles.

We brought the sea-breeze up with us, saluted, and followed the flag into the magnificent harbour of[36] Rio de Janeiro, and came to an anchor. There I saw for the first time the white flag of France flying on board the Jean Bart, 74, also the Stars and Stripes of the United States on board the Franklin, 74. After the Brazilian national flag we saluted that of Lord Cochrane, on board the Don Pedro, as High Admiral of the Brazilian Navy, with 19 guns.

I saw that gallant and extraordinary, but ill-used man, Lord Cochrane, who came on board to return Captain Hunn’s visit. He was at this time, in the estimation of the Old World and the New, the greatest man afloat. He was tall and thin, of powerful build, with close-cut red hair.

I indeed felt proud when, on my Captain’s presenting, he shook me by the hand. One of the last books I had read at the Naval College was his action in the Speedy sloop of 14 guns, with a crew of 54 men, when he captured the Spanish frigate El Gamo, Captain de Torres. It was on this occasion that Cochrane admitted he had nearly caught a Tartar. While cruising off the coast of Spain, he saw what he took to be a large merchant ship. On drawing near, she opened her hitherto disguised ports, and disclosed the broadside guns of a frigate. Without going into further details, she was carried by boarding. There were killed on board the El Gamo the Captain and 13 seamen, and 41 wounded, exceeding in number the whole of the officers and crew of the Speedy. The second in command of the El Gamo succeeded in obtaining from Cochrane a certificate stating that he had fought his ship like a true Spaniard.

Captain Hunn took a house at Boto Fogo, one of those beautiful inlets in the harbour facing the Sugar-loaf, about three miles from the town. I was again kindly included in the family party. The[38] principal Portuguese and most of the English merchants had residences there.

At midnight a salute of 101 guns was fired from the batteries in honour of the birth of a Prince and future Emperor. The salute was repeated at daylight, noon (when we joined), sunset, and midnight.

Lord Cochrane had sailed with his fleet: an embargo was laid on all ships for three weeks. Picnics and every sort of amusement went on.

The embargo being removed, we sailed with the early breeze in company with some 500 sail of all nations. The show of white canvas was a beautiful sight. When outside and in the open we spread out like a fan.

Arrived off Bahia—Bahia de los Todos Santos (Bay of All Saints)—perfectly sheltered and capable of holding the fleets of all nations. Cochrane had been before us, and the Brazilian flag had replaced that of Portugal. We anchored on the west side of the bay, off the city of San Salvador.

It appears that in June, about three months back, Lord Cochrane, with the Brazilian squadron, consisting of the Don Pedro, 74, and three frigates, manned, with the exception of 170 English seamen he had in his flagship, by natives, appeared off this place, which was then in possession of the Portuguese Government.

He had no sooner made the entrance than he discovered the enemy’s fleet of thirteen sail standing out to prevent the threatened blockade. Cochrane formed his line-of-battle, and immediately bore down and put his enemy to flight. Nothing occurred beyond the hammering some of them got, but it led to the establishment of the blockade of their port.

In the meantime Cochrane had prepared fireships.[39] One dark night he stood in in his flagship alone to reconnoitre. On being hailed, he replied that it was an English ship. However, the consternation was great when it was announced to the Portuguese Admiral and officers, who were then at a ball, that Lord Cochrane’s fleet was in their midst.

A panic was established: the evacuation of San Salvador determined, and on July 1 a Junta was formed to carry on the Government in the name of the Brazilian Empire.

We found trade going on in the same way as I suppose it had been under the Portuguese flag. It made but little difference to the unfortunate slaves as to the colour of the bunting that flew over them; although most of the Portuguese merchants were in favour of the mother-country.

The new Imperial troops were not much, although they exhibited on their shakos “Libertad o Muerte.”

One afternoon the Captain ordered me to take a despatch on board the Tweed to the commanding officer. On going towards the landing-place I met Nightingale, the coxswain, who informed me that he was not allowed to pass the guard. On my remonstrating with the officer, who I noticed was not the same who was on guard when I landed, I showed him the back of the letter, which appeared to make matters worse. Now, I believed myself to be in charge of a despatch of importance.

Having, on landing, noticed that the muskets in the racks at the guard-house were beautifully polished; and thinking them more fit to look at than for use, I told old Nightingale to be ready for a rush. The crew were up to the occasion, and before a musket could be got at, the sentry was on his back, and we were all in the boat,[40] with the exception of Harrison, a coloured bowman who had a slight bayonet scratch on the back of his neck, being slow in casting off the painter.

After a while a few musket-balls dropped in the water short of the gig. Of course there was a row, but I think it was our Consul who explained that the Brazilian officer was wrong in attempting to stop a British officer in uniform, however small. Nothing satisfactory to either party was arranged.

We left Bahia on the 17th, and arrived at the open and exposed anchorage of Pernambuco on August 23. We found Lord Cochrane had arrived with his squadron on the 18th.

The “Patriots,” as they called themselves, had not been idle. Count Manuel Carvalho Pas de Andrade had been elected President: he had already denounced Don Pedro as a traitor, and was endeavouring to excite the neighbouring provinces to form themselves into a federation on the model of the United States, under the title of “Confederação del Ecuador.”

A few days after our arrival Lord Cochrane came on board the Tweed, but I do not think there was much cordiality between him and our Captain. An attempt at arrangement by correspondence having failed, Lord Cochrane threatened to bombard the city.

The shoal-water and exposed anchorage would not admit of the fleet going in, but on the night of August 27 I witnessed the pretty effect of mortar shells flying between the small craft and the forts protecting the town. The damage done was not, however, much on either side.

The following day we were disappointed at seeing Lord Cochrane sail for Bahia, which he did to[41] get wood for rafts and to procure vessels of light draught, capable of carrying mortars. He left a portion of his fleet behind to continue the blockade. The Brazilian General, Lima, who had been landed with his troops about seventy miles distant at a place called Alagoas, hearing of the panic established, pushed on for Pernambuco, where he arrived on September 11, and, assisted by the blockading squadron, made an attack on the town.

President Carvalho retreated to the suburbs, which were protected by an inlet of the sea, and, having broken down the bridge, prepared to defend himself. However, his heart failed him, for during my middle watch the following night a catamaran came alongside with the would-be President fully accoutred, just as he had left the fight, having come to claim the protection of the British flag!

All the next and two following days the fight was kept up with much spirit, the place being gallantly defended while the “brave” Count Carvalho looked on from the deck of the Tweed. We were so near that on one occasion a shot fired at one of the blockading squadron passed over our mastheads.

On September 13 Brazen, 20, Captain W. Willes, arrived from the coast of Africa. In running for the anchorage whilst hostilities were going on, her English ensign was taken for a ruse on the part of Lord Cochrane’s squadron, and she was fired into, two round shots taking effect. One cut away the hammock netting and tore up part of the quarter-deck. Luckily no one was hurt.

When Lord Cochrane returned to Pernambuco, he found Lima in possession. He then sent an officer on board the Tweed to request that the “rebel” and “traitor” Carvalho might be given up.

[42]

Three days later the Brazilian fleet and forts fired a royal salute in honour of the victory, in which, in obedience to an order signalled by the Captain of the Brazen, we joined.

Carvalho embarked on board the Brazen, and, much to our disgust, under a salute. I had to part with my two little playfellows, who, with Mrs. Hunn, also went home in her.

Directly the Brazen loosed sails, the Brazilian fleet did likewise, and, seeing this, our Captain interpreted it (or pretended to) as a device on the part of Lord Cochrane to take Carvalho out of the Brazen by force, and we also prepared to weigh and clear for action. However, it all ended without smoke.

We sailed on September 22, not sorry to get away. We had been six weeks rolling—at times, our main-deck ports in the water; holding no communication with the shore, and, with the exception of the fighting in which, as we would take no part, there was little to excite interest.

We youngsters amused ourselves, meanwhile, fishing, which we could only venture to do at night, and then out of the mizen-chains, hid by quarter-boats.

One day, when I was sitting in the gig astern of the ship, a school of whales came into the bay, like so many frolicsome porpoises; and so near did they come that I found my way to the ship’s deck up the Jacob’s ladder.

We left Pernambuco on our return to Rio, where we arrived October 2. This was a jolly place for us mids. There is no nicer harbour for boat excursions, rides, picnics, etc., fun, in which we joined those of other ships. One of our lieutenants, Pat Blake, was[43] a favourite with us. There were lively fellows in the squadron, one of whom, named Hathorn, was lent to us from the flagship.

Early in the morning, it being calm, we were towed out of the harbour by boats, on which events those of the foreign men-of-war always assisted.

On the 24th we came to in Maldanado Roads, an interesting place. The only thing that struck me as odd was, if you made a purchase which cost less than a dollar, they chopped that coin in pieces to give you change.

We sailed the following day, and arrived at Rio de la Plata, a large muddy river, unworthy of the name—porpoises and seal in plenty. I had many rifle shots at the round head of the latter, with their large bright black eyes; but they were too quick for me.

Horses were in plenty. If you hired one for a ride, the owner bargained that in case it died you must bring back the shoes—they only shod the forefeet. It was a wild and open country; everyone appeared mounted as well as carrying a lasso, which would bring you to the ground with more certainty than a pistol-shot. We never ventured alone, but took long rides into the country.

We sailed from the River Plate, and got back to Rio October 29. Found Aurora, Blonde, and Jaseur. Blonde a beautiful 48-gun frigate, Captain Lord Byron, who had on board the bodies of the late King and Queen of the Sandwich Islands, who had fallen victims to the measles while on a visit to England.

There was in the Rua de Rita, over a shop-door, a large gilded metal cock that had for years resisted the attempts of the midshipmen of the British fleet; it[44] was not strong nor heavy, but placed out of reach. There were watchmen about, as it had been often in danger, and it was for the benefit of the bird that Jack Hathorn got lent to the Tweed, bound for the River Plate, that he might find a suitable lasso.

Days, or rather nights, passed without an opportunity: rain did not fall heavy enough; the moon would peep out. At length a storm, that had been threatening the early part of the night, broke with great violence. It was as dark as pitch. Cocoanut-oil lamps put themselves out; heavy stones that we carried through the dark were thrown down with a yell, unheeded by the guardians of the night; while Jack Hathorn and a chosen few, with his Monte Video lasso as well as a properly-prepared instrument, loosened the claws of the noble bird, which alighted in a downpour of rain on a pile of midshipmen’s cloaks, and was borne off.

The sentry at the guard-house, under shelter of his box, did not trouble himself to ascertain how drunk was the comrade being conveyed to the boat which had been so long waiting. How sorry I was that my diminutive size prevented my having shared in this triumph! I hear the bird may now be seen in the hall of the Hathorn family at Castle-Wigg, in Wigtonshire, with a scroll in its beak describing the above.

Accidents will happen in the best regulated families. More than two courts-martial took place during our stay at Rio; but my friend Lieutenant Blake was acquitted and discharged into the Aurora, which ship was towed out of harbour, and sailed for England, December 16.

As gig’s midshipman, I was much on shore; and, waiting for the Captain, amused myself in the[45] extensive market, furnished as it was with every tropical fruit and flower. But my favourite amusement was to watch the monkeys, from the beautiful little marmoset to the more mischievous green species. One of these usually wiped his hands on my white trousers. Although not allowed, the evening before we sailed I smuggled my little friend on board in the Captain’s cloak-bag, and stowed him in the scuttle of the midshipmen’s berth.

On Christmas Day we got our usual tow out of the harbour, and made sail for England. Two days later we unbent cables and stowed anchors.

After a while it came to my turn to dine with the Captain. One of my facetious messmates thought it good fun to give my little prisoner a run. By instinct he made his way to the Captain’s cabin. Seated on the deck, surveying the apartment, the Captain spotted him, and ordered the sentry to throw the beast overboard. On the first move of the marine, the monkey with a bound was on my shoulder, his little hands clasped round my forehead, chattering and grinning; there being no mistake as to the owner. I suppose the Captain was moved by the affection of the little fellow. We were dismissed.

Nothing of importance occurred during our long voyage. On February 26 made the Lizard at daylight and bent cables. We had a chain-cable, which was only used once; but every month we had to rouse the thing on deck and knock the shackling-bolts out, in order to anoint them with some white mixture.

We ran through the Needles, saluted flag, and came to at Spithead.

[46]

The Tweed

The Tweed at Spithead became one of the Channel Squadron, and commenced refit.

First visit was to my brother Tom at the College. Landing in the dockyard, our shortest route lay through the lower-mast and boat-houses. In the latter we found one of our masters’ mates returning condemned, and drawing new stores. He, too, wanted to see my brother; so, leaving the stores to the care of the warrant officer, he joined us.

I must attempt to describe this good-tempered salt, Peter Dobree by name. He was from Guernsey. Although not too young, he was the junior of our masters’ mates; and had a shock head of red hair which protruded from under his hat. I was told that, when on board the hulk during our outfit, if he saw a child about the deck unprotected, he would imitate its cry and a dog’s snarl so closely that half the wives would rush to the rescue. It did not matter how often he repeated the joke, the effect was the same. When he got leave to go on shore late in the evening, he scorned the use of a boat; he would jump overboard and swim to the logs—this, too, in the winter months. He kept a change of raiment at the “Keppel’s Head.”

[47]

Dobree followed us to the College, where I found Tom. It was winter; we could only make a short tour. Dobree, passing the area near Dr. Inman’s, espied a large round dish of setting cream. He was down the steps and his mouth in the cream, when the dairymaid pushed his head in, to which the cream adhered. It was just closing time as he escaped through the storehouse doors.

I started by mail with my monkey, and the following evening was at Quidenham. Jacko appeared to take possession. The excitement he caused was great. At first he would not trust himself out of my reach, but was only too much at home afterwards. The ship was again wanted for service. I had not time to visit my sister Anne, who had in February 1822 married Mr. Coke.

I was much vexed, when I got back, to find that some good-natured messmate had on Sunday afternoon given my brother at the College a small bottle of first-rate Jamaica. Now Tom’s position in the ranks at prayers was, unfortunately, just in front of the Governor. During the short service the poor boy lost his balance, and prostrated himself on the floor. The next morning in the cupola he ascertained what a birch administered by a Blue Marine sergeant was like.

We sailed in company with a small experimental squadron. Got as far as Lymington and back, through Spithead to off Dover, Dungeness, and Downs. In the latter anchorage lay the Ramillies, 74.

In addition to her Captain and officers, she had 103 lieutenants and 33 assistants borne for coastguard service. She was a show ship, and for the convenience of ladies getting on board had a large[48] cask fitted with a seat. On the bottom, outside, was painted a clown’s grinning face, which made people laugh, while the occupant in mid-air believed her little ankles were being seen.

We were ordered to Harwich, where we embarked Rear-Admiral Plampin, and saluted him with 13 guns. It was the end of the week before we had embarked suite and luggage and sailed.

Still no hurry, and, with occasional anchorings it was April 1 before we reached Cork to assume the command in place of Lord Colville, who had sailed in the Semiramis, which ship returned on May 7 without his lordship, when we transferred our flag.

We were glad to get back among our kind and hospitable friends.

We had, however, a visit from a pedlar, whose wares were various. He was rash enough to venture on the lower deck of a man-of-war, whose inhabitants were mixed. Now, Dobree, who, I suppose, had got tired of snuffing the purser’s dips with his fingers, invested in a pair of plated snuffers.

Unluckily, before the pedlar had cleared out, and on the third time of asking, the plating came off the snuffers. The pedlar bolted, and his box followed, the contents dispersed in front of the marines’ mess. Luckily they spread no further and were recovered.

I believe I was the only loser, inasmuch as the pedlar lodged a complaint with the kind and good Mrs. Dunsterville. The pedlar knew no names, he could only describe his enemy as the “foxy-headed gintleman.” As I was the only “gintleman” with red hair Mrs. Dunsterville knew, my invitations to that cheery establishment ceased, and her son John, my messmate, never came on board if he knew of it.

[49]

We left Cork, and arrived at Portsmouth on the 12th.

Captain going away, and as there would be no particular service for gig’s midshipman, I got him to endorse a cheque on Woodhead and Co. for £5, and obtained the usual leave from the First Lieutenant to go on shore.

With a small bag I took up my quarters at the “Keppel’s Head,” intending to enjoy myself.

On the afternoon of the third day, before returning on board, I was taking a parting cup of tea with Mrs. Harrison, the landlady, when the sergeant of marines from the Tweed, trailing a halbert, for which there was no room, put his head in, without taking his shako off, stated that I was his prisoner, and withdrew.

The back window of the parlour opened into Havant Street, by which I found my way with the small bag to the “Hard,” where my faithful water-man, James Sly, instead of taking me on board the Tweed, conveyed me to Ryde Pier.

I knew some of the good fellows of the 60th Rifles, Colonel A. Ellis, quartered at Newport. After a few days’ enjoyment, money expended, I returned to the Tweed, without the help of the sergeant. Of course I was put under arrest.

Sailed from Spithead on a cruise to the eastward, reaching Sheerness the following day, which we left and anchored off Boulogne.

The Duke of Northumberland and suite having been to attend the coronation of Charles Dix, on His Grace’s re-embarking on board the Lightning, we fired a salute of 19 guns, which we, as well as the Brazen, 28, Captain Willes, repeated on His Excellency’s landing at Dover.

[51]

We returned to the Nore and remained until 12th, when we started on a pleasant summer cruise along the east coast.

Exchanged numbers with the Glasgow, Captain Hon. J. A. Maude, a 50-gun frigate under sail. No prettier sight! She had fitted out at Deptford. We anchored in Yarmouth Roads. The east coast was seldom frequented by anything larger than a revenue cruiser.

We were crowded with visitors. I had some kind Wilson cousins. One day, when they were not on board, I selected two pretty young women to show round. My dignity was hurt; when I helped them into their boat they offered me sixpence, my uniform having been taken for livery, but not liking to hurt their feelings I pocketed the coin.

Fired royal salute, His Majesty’s birthday. We sailed from Yarmouth; 22nd, anchored off Grimsby; next day joined party to Hull; the pilot of the packet we were in sounded his way with a pole.

Visited Scarborough, a very different place, but did not stay long, Captain thinking anchorage exposed.

Off the Dogger Bank we caught a lot of cod-fish. On August 4 we came into Peggy’s Hole, North Shields.

Sent an officer and party to Sunderland to quell small disturbance. In four days they returned, and we sailed for Leith Roads. We really enjoyed Edinburgh.

The Parthian, 10, Commander Hon. George Barrington, arrived. Next day we sailed, getting back to Spithead on 28th.

The worst of belonging to the Channel Fleet, you were never safe to go any distance; but we had many kind friends in the neighbourhood. One of[52] my brother mids was Charles Patterson, the son of an Admiral, who lived at Cosham. He was a friend of my Captain, and I often stayed with him. The old gentleman was kindness itself, with no end of good stories. He swore a good deal, but only at himself: his heart, or liver, etc.

The latter part of his service as Captain was as Governor of Porchester Castle, which was, and will always be, a most interesting ruin. Built by the Romans, in the fourteenth century it was used by King John as a State prison.

At the period of the Revolutionary wars it held French prisoners, and Dutch sailors taken at the battle of Camperdown.

The Admiral had a pretty daughter, with whom we midshipmen were in love. Mrs. Patterson was so kind to us. She was a wonderful horsewoman. I never saw the Admiral in any other costume by day than yellow leathers and mahogany tops. Miss Patterson had a collection of animals carved by the prisoners out of their meat-bones. I have some of them now.

We got notice to receive on board Bishop Inglis and family for Nova Scotia.

While at the Naval College I had watched with interest the building of the Princess Charlotte, not only on account of her grand proportions, but there were associations connecting the name of that fair Princess with our family, my grandmother, Lady de Clifford, having been governess to Her Royal Highness.

In those days a ship of the line frequently remained ten or twelve years on the stocks. To stand on the keel near the sternpost and look forward, at a time before beams or planking of any sort had been placed, and to reflect that 800 full-grown oak-trees[53] had been expended in her construction, made you lost in wonder. The Princess Charlotte was laid down in 1812, and was to carry 120 guns and have a round stern: an innovation in those days on the present square old Victory.

Thursday, September 13, was the day fixed for the launch, ushered in by a royal salute, announcing the arrival of Leopold, Crown Prince of Belgium, who was to christen her.

Being anxious for a good place, I landed early from the Tweed. Climbing to the top of a building-shed I commanded a fine view. Spectators assembled in thousands.

As large ships were only launched on the top of spring tides, a larger quantity of water than usual had been admitted into the floating-basin.

When the moment arrived the great ship started, and the lock of the dry-dock burst. On the one hand I saw the huge ship majestically sliding into the harbour; while on the other, hundreds of human beings were being precipitated into the dry-dock by the bursting of the lock and breaking of the bridge, which was crowded.

Some of those who were in the centre were carried the whole length of the dock and managed to escape.

Full particulars may be found in the Hampshire Telegraph, September 13, 1825.

Having embarked the Very Rev. J. Inglis, Bishop of Nova Scotia, Mrs. Inglis, and two tall, handsome daughters, we sailed for Halifax. The summer was over, and we had no time to lose, as we hoped to escape being frozen in for the winter in Canada.

Things generally go on smoothly while ladies are on board. However, we were detained two days at Cowes and ten at Falmouth.

[54]

We anchored in Fayal Roads on 21st until 23rd, when we again sailed into more bad weather.

It was the 7th before we reached Halifax. How thankful our poor passengers must have been! We saluted the flag of Rear-Admiral W. T. Lake; afterwards landed our good Bishop under salute of 13 guns.

The Bishop and family did all they could to make our short stay pleasant, particularly to us youngsters. A ball was given, at which I was too shy to dance with one of the tall and handsome Miss Inglises. General Sir James Kempt was the Governor, one of the most popular as well as the smartest officers I had seen. Years afterwards he seconded Lord Lyndoch’s proposal for me as a member of the United Service Club.

We received on board Commander Canning and officers of the Sappho for passage home, she having been wrecked on the coast. The flagship Jupiter, 60, shifted nearer entrance preparatory to going into milder winter quarters.

In proof that we had remained long enough, our sails were frozen to the yards. It took marling-spikes to hammer the gaskets before the sails could be loosed.

We sailed after breakfast, with the Pelter, 10, brig in company. I fancy junior commanders don’t care about being in co., and after Wednesday evening we saw no more of her.

December 1 found us in 43° north latitude; unpleasant mornings for washing decks. I saw but little of our passenger, the Prime Minister’s son, nor did he much of his half-uncle.

Just at dark came to in Plymouth Sound. Sailed 13th, arriving at Spithead 14th.

[55]

The Tweed

Had to attend my Captain at a court-martial which caused an unusual sensation. It took place on board the Victory in Portsmouth Harbour, with all established pomp and ceremony. The president was Rear-Admiral of the White, Sir William Hall Gage. On opening the Court, the ten senior Captains of those assembled were sworn; the remainder were informed their services were not required. The Provost-Marshal, with drawn sword and cocked hat, in charge of the prisoner, took position at the lower end near the right side of the table, on which lay the prisoner’s sword with handle towards him.

The following Captains formed the Court, taking their seats on alternate sides of the table, according to seniority, the senior on the right of the president:

[56]

The prisoner was Captain of the Ariadne. He was tried for having purchased a slave negress at Zanzibar, and taken her to sea. She mysteriously disappeared off the coast of Africa.

The trial lasted three days. When the Court reopened for the last time, the members had resumed their cocked hats, the prisoner’s sword lay on the table with the point towards him. He was dismissed the service of His Majesty King George IV., and Captain Adolphus Fitz-Clarence appointed to the Ariadne.

Received Colonel Dashwood, appointed Consul at Mexico, a guardsman, and of course a good fellow: it was not until the 25th that we got his luggage and fixings on board. In the afternoon we sailed, but not in a hurry; Captains with Government passengers seldom are. We anchored at Cowes and Yarmouth; next move we ran through the Needles.

[Feb. 15.]

We were glad to find ourselves out of the cold, and came to in Funchall Roads. We saluted the Portuguese flag: the pinnace, instead of being astern, was fast to the guess-warp boom; her planking so shook that she had to be hoisted in. Next day the First Lieutenant was invalided, and went home in the Eden, 28. On shore we enjoyed the usual kind hospitality. I had lost my female playfellows, and, although I did not grow, I joined my seniors in the rides and picnics; that at the Corral, for enjoyment and scenery, is not to be beaten.

On sailing, we got unusually quick into the north-east trade; sails trimmed accordingly, ropes coiled up, and ship prepared for painting.

We came to in Carlisle Bay, Barbadoes. Sent boats and party on shore for water, which I was allowed to join.

[57]

We sailed. No scenery in the Mediterranean can be more beautiful than that we experienced running past the beautiful Islands of Porto Rico, St. Domingo, and distant view of Cuba; sea clear and smooth; flying-fish, dolphin, and sea-birds.

Running into Port Royal, we saluted the flag of Vice-Admiral Sir Lawrence Halstead.

The next morning I saw the Governor, the Duke of Manchester, who had driven down from his hill residence to meet our Captain—his conveyance, a random tandem: two leaders abreast and a horse between the shafts.

We left Port Royal, running down the trade, and reached Vera Cruz on the 19th, saluting the Mexican flag with 19 guns.

Royal salute, it being His Majesty George IV.’s birthday. Same day Governor-General of Vera Cruz came on board, and was saluted with 19 guns. It took a few days before the Consul’s house at Xalapa was fit to receive him; he left us under a salute of 7 guns, but what he seemed to prefer were three hearty British cheers.

The Gulf of Mexico is for dollars what the bank of Newfoundland is for fish; owing to the number of slavers, who, when their trade is slack, are not above doing a bit of piracy, the merchants care not to trust their money to traders, while Captains of the Royal Navy were keen freight collectors.

I copy the following from my Navy List:—

“Proclamation by His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, Regent of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, in the name and on behalf of His Majesty.

“The freight paid for the conveyance of treasure on board a man-of-war in the West Indies 2[58] per cent. On the other side of the Capes Horn and Good Hope, a half more. Of this freight, one-fourth to Greenwich Hospital, one-fourth to the Admiral, or Admirals, on the station, and the remaining two-fourths to the Captain.”

I observed that half the pier at Vera Cruz was built of lumps of iron, such as have since been called “Seeley’s pigs.” They had been landed at different times to make room for specie. The Admiral took care to keep a cruiser not far off, so that the arrival of a convoy of specie from Mexico was quickly communicated. Now and then a wicked little mail brig from Falmouth would drop in, and walk off with what she could carry. Cochineal paid freight, but it was too bulky, and required time. Our turn had not arrived, so we kept between Tampico and Vera Cruz, learning something.

We came to off Tampico. A more uninviting open roadstead could not be: in-shore the mouth of a large river, a bar and heavy surf breaking across and beyond. We lay at single anchor ready to face foul weather.

Fresh water was only to be had by sending our boom-boats, with casks, up the river, beyond high-water mark, and remaining the night. When you got back, it was doubtful whether the state of the bar would allow deep-laden boats to cross. To us mids, who had no responsibility, it was great fun. Alligators, turtle, and sharks were numerous; these were seen to advantage from the shore, when waves came rolling in, lifting the monsters into the light. The beach was covered with large mahogany-trees and broken branches, washed down by the rain floods.

It was my turn to go with the water boats—to me[59] a picnic. Over the bar, we pulled up the river, tide with us, intending to anchor off-shore for the night; but first we had to cook a substantial meal under the trees. I was about to jump from the bow of the pinnace on to a dead tree covered with mud, when the bowman put his hand on my shoulder, and pointed out that my “dead tree” was a live alligator. I ran aft and seized a marine’s musket, already loaded. The reptile at that moment lifted his upper jaw, and I sent a ball into his stomach. He was assailed with stretchers and cutlasses, and soon became harmless.

At daylight we filled our casks from alongside, and pulled easily down with the tide, alligator in tow, and so alongside. As I could not pickle the brute, I was anxious to obtain the bullet, it being my first shot at big game, and got the good-natured Assistant-Surgeon Taylor to dissect him. While performing, the doctor complained of the strong smell of musk, which I attributed to the ball he was in search of. The alligator measured eleven feet from tip of nose to end of tail.

We sailed for the Havana. On June 6, as we passed in, close under the famous Moro, we were hailed through a huge brass trumpet, in some unintelligible jargon, which was replied to in much the same coin.

I was now in the famous Havana, of which I had heard (and seen, as far as pictures go) so much at Quidenham. My grandfather, assisted by his brothers, General William and Commodore Augustus Keppel, had captured it in 1762.

Galatea, 42. Sir Charles Sullivan, Bart., arrived from Carthagena; secured along the spritsail yard was the skin of a huge alligator. The Spanish Main was unhealthy, yet famous for the collection of[60] dollars; but this gallant officer, the moment he had two of his crew down with fever, left the dollars for the next cruiser to collect.

Sailed from the Havana on June 13 to rejoin the flag, arriving off the port on the evening of July 5: we had to wait for the next day’s sea-breeze to take us in.

On running for Port Royal we stuck on the middle bank, the sea-breeze, with its accompanying swell, having set in. We did not shorten sail, as we drew only about three inches less than the water over the brittle coral reef. My station was in the main top; the sea and down to the bottom as clear as crystal: it was a pretty sight, when the swell lifted the ship and eased her down. As we proceeded, the variety of beautiful fish and animals dashed from under, on both sides. Got into Port Royal with our bottom a little cleaner than it was. I believe the mishap occurred by the Quartermaster not rightly distinguishing the black pilot’s pronunciation of “starboard” and “larboard.” Found here the magnificent hospital and store-ship Isis, 50, with flag, Rattlesnake, 28, and Harlequin, 18.

Sent pinnace with specie to Kingston. We were not wanted long; I had only time to make the acquaintance of one Johnnie Ferron, a jolly Frenchman, who kept a store, in which was to be found everything, even to a pair of skates, and three pretty daughters. We were ordered on a cruise: there were few dollars, but we might tumble across a slaver.

Sailed for the eastward, and as trade wind and current were the same way, we had to work to windward, unless, as frequently happened near land, we got becalmed with islands of Cuba and St. Domingo in sight.

[61]

At daylight we saw a rakish-looking black schooner, running before the wind under studding sails. She no sooner made us out than she hauled to the wind, and was soon out of sight.

Four days after we ran into Port-au-Prince, and saluted the Black Republican flag with seventeen guns.

Mr. Mackenzie was our Consul, and through him we saw quite enough. There were negroes parading about in the cast-off uniforms of our infantry and cavalry, helmets and jack-boots, but nothing to ride.

The most beautiful island in the Far West was the first landed on by Christopher Columbus. Some of his followers fancied they smelt gold; he left a party behind, from the effects of which Hayti never recovered.