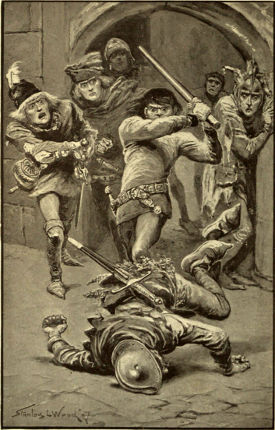

BERTRAND DEFENDS THE JESTER

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Under the Flag of France, by David Ker

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Under the Flag of France

A Tale of Bertrand du Guesclin

Author: David Ker

Illustrator: Stanley L. Wood

Release Date: September 14, 2014 [EBook #46855]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK UNDER THE FLAG OF FRANCE ***

Produced by Shaun Pinder, Sonya Schermann, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

BERTRAND DEFENDS THE JESTER

I must plead guilty to having, for the purposes of the story, placed my hero’s castle (which unhappily no longer exists) much nearer to Rennes than it actually was; but the chief events of his life are given here very much as I found them in the old French chronicles.

| Chap. | Page | |

| I. | The Broken Bough | 1 |

| II. | Facing a Monster | 7 |

| III. | A Mysterious Message | 16 |

| IV. | Bertrand’s Dream | 29 |

| V. | A Timely Rescue | 37 |

| VI. | Mighty to strike | 51 |

| VII. | A Strange Tale | 67 |

| VIII. | Lance to Lance | 79 |

| IX. | Into the Dragon’s Jaws | 93 |

| X. | The Wages of Judas | 103 |

| XI. | A Midnight Battle | 110 |

| XII. | Crowning an Enemy | 126 |

| XIII. | A Red Stain | 133 |

| XIV. | The Black Death | 140 |

| XV. | A Night Alarm | 148 |

| XVI. | The Boldest Deed of all | 161 |

| XVII. | The Haunted Circle | 168 |

| XVIII. | A Phantom Warrior | 177 |

| XIX. | In a Robber Camp | 189 |

| XX. | Doomed | 194 |

| XXI. | The Black Wolf | 206 |

| XXII. | A Clever Stratagem | 215 |

| XXIII. | Possessed Swine | 222 |

| XXIV. | Through the Darkness | 235 |

| XXV. | A Case of Conscience | 246 |

| XXVI. | Crescent and Cross | 259 |

| XXVII. | An Astounding Revelation | 268 |

| XXVIII. | Plot and Counter-plot | 276 |

| XXIX. | Treachery | 283 |

| XXX. | A Village Festival | 299 |

| XXXI. | A Strange Meeting | 313 |

| XXXII. | News of an Old Friend | 326 |

| XXXIII. | The Last Sunset | 337 |

| Page | |

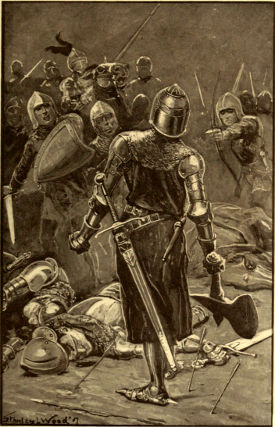

| Bertrand defends the Jester | Frontispiece 61 |

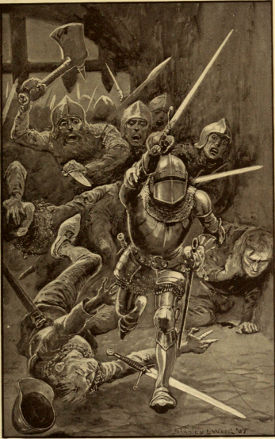

| Bertrand grapples with the Wolf | 9 |

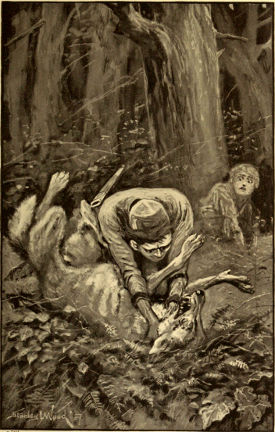

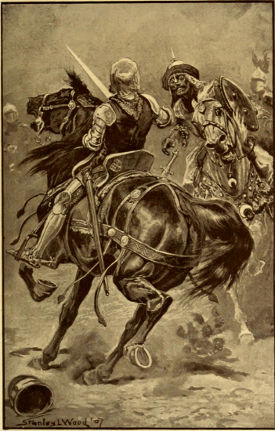

| The Black Champion conquers | 88 |

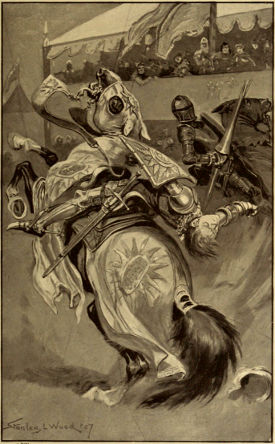

| “The Black Knight turned like a Hunted Lion” | 163 |

| “The Shouting Assailants burst in” | 220 |

| “He stared at his Foe’s Revealed Face” | 266 |

“What place is there for me on the earth? I would I were dead!”

Startling words, in truth, to hear from any one’s lips; and doubly so from those of a boy of fourteen, with his whole life before him.

It was a clear, bright evening in the spring of 1334, and the setting sun was pouring a flood of golden glory over the wooded ridges, and dark moors, and wide green meadows, and quaint little villages of Bretagne, or Brittany, then a semi-independent principality ruled by its own duke, and little foreseeing that, barely two centuries later, it was to be united to France once for all.

Over earth and sky brooded a deep, dreamy stillness of perfect repose, broken only by the lowing of cattle from the distant pastures, and the soft, sweet chime of the vesper-bell from the unseen church tower, hidden by the still uncleared wood, through one solitary gap in which were seen the massive grey battlements of Motte-Brun Castle, the residence of the local “seigneur,” or lord of the manor. A rabbit sat upright in its burrow to clean its furry face. A squirrel, halfway up the pillar-like stem of a tall tree, paused a moment to look down with its small, bright, restless eye; and a tiny bird, perched on a bough above, broke forth in a blithe carol.

But the soothing influence of this universal peace brought no calm to the excited lad who was striding up and down a small open space in the heart of the wood, stamping fiercely ever and anon, and muttering, half aloud, words that seemed less like any connected utterance than like the almost unconscious bursting forth of thoughts too torturing to be controlled.

“Is it my blame that I was born thus ill-favoured? Yet mine own father and mother gloom upon me and shrink away from me as from one under ban of holy Church, or taken red-handed in mortal sin. What have I done that mine own kith and kin should deal with me as with a leper?”

In calling himself ill-favoured, the poor boy had only spoken the truth; for the features lighted up by the sinking sun, as he turned his face toward it, were hideous enough for one of the demons with which these woods were still peopled by native superstition.

His head was unnaturally large, and covered with coarse, black, bristly hair, which, worn long according to the custom of all men of good birth in that age, tossed loosely over his huge round shoulders like a bison’s mane. His light-green eyes, small and fierce as those of a snake, looked out from beneath a low, slanting forehead garnished with bushy black eyebrows, which were bent just then in a frown as dark as a thunder-cloud. His nose was so flat that it almost seemed to turn inward, and its wide nostrils gaped like the yawning gargoyles of a cathedral. His large, coarse mouth, the heavy jaw of which was worthy of a bulldog, was filled with strong, sharp teeth, which, as he gnashed them in a burst of rage, sent a sudden flash of white across his swarthy face like lightning in a moonless sky.

His figure was quite as strange as his face. Low of stature and clumsily built, his vast and almost unnatural breadth of shoulder and depth of chest gave him the squat, dwarfish form assigned by popular belief to the deformed “Dwergar” (earth-dwarfs) who then figured prominently in the legends of all Western Europe. His length of arm was so great that his hands reached below his knees, while his lower limbs seemed as much too short as his arms were too long. In a word, had a half-grown black bear been set on its hind legs, and arrayed in the rich dress of a fourteenth-century noble, it would have looked just like this strange boy.

All at once the excited lad stopped short in his restless pacing, and, as if feeling the need of venting in some violent bodily exertion the frenzy that boiled within him, snatched from its sheath his only weapon (a broad-bladed hunting-knife, half cutlass and half dirk), and with one slash cut half through the thickest part of a large bough just over his head.

His arm was raised to repeat the blow and sever the branch entirely, when a new thought struck him, and, flinging down his weapon, he seized the bough with both hands, and threw his whole strength into a tug that seemed capable of dislodging not merely the branch, but the tree itself.

The tough wood quivered, cracked, and gave way, and a second effort—which hung the boy-athlete’s low, broad forehead with beads of moisture, and made the veins of his strong hands stand out like cords—wrenched the bough away altogether.

For a moment the young champion’s harsh but striking features brightened into a smile of joyful pride, natural enough to one who felt that he possessed surpassing bodily strength in an age when bodily strength and prowess were the most valued of all qualities. But the smile faded instantly, and the sullen gloom settled down on his dark face again, more heavily than before.

“Methinks yon gay cousins of mine,” muttered he, with a grim laugh, “would be hard put to it to do the like, though they call me dwarf and lubbard, and look askance at me as if I were a viper or a toad. I feel, in truth, that though I am not one to wear the dainty trappings of a court-gallant and bask in ladies’ smiles, I have it in me to approve myself a tried man-at-arms on a stricken field, and make my name dreaded by the foes of my country and liege-lord. But what avails it, if I may never find a chance to show what I can do?”

At that very moment, as if in direct answer to the bitter query that the fiery youth had unconsciously spoken aloud, a clear, sweet voice rose from amid the clustering leaves, singing as follows:—

As the song proceeded, the moody lad bent forward to listen with a visibly brightening face, though in an attitude of reverent awe; for his first thought was one that would have occurred to any man of that age in his place—that the voice he heard was that of his patron saint, or of an angel sent down from heaven to comfort him in his distress.

But ere he could utter the devout thanksgiving that rose to his lips, he was checked by the sudden appearance of the singer himself.

From the thickets issued a boy about his own age, with a huge faggot of dead wood on his back. He was barefooted and barelegged, and what little clothing he had was sorely tattered and soiled; but the wholesome brown of his tanned face, and the springy lightness of his step under that heavy burden, told that his rough life agreed with him. It was plain, however, from the wandering look of his eyes, and the bird-like restlessness of all his movements, that he was one of the poor half-witted creatures so numerous then in every part of France, and pretty common even now in some remote parts of it.

At sight of the young noble (whose grim features had certainly nothing reassuring in them at the first glance) the simpleton came to a sudden halt, and looked not a little scared. Nor was this surprising; for so many and so tyrannical were the privileges claimed by the landed gentry in an age when all France was divided into beasts of prey called nobles and beasts of burden called peasants, that (though among the sturdy Bretons there was happily less of the frightful oppression that disgraced France proper) this poor lad could not tell that he might not have committed, by picking up these dry sticks in a wood that virtually belonged to no one, some offence rendering him liable to punishment; and punishment was no trifle in the fourteenth century, whether inflicted by the law or against it.

But ere a word could be spoken on either side, there came a sudden and startling interruption.

Fully occupied with his supposed enemy in front, the wood-boy knew nothing of the far worse peril that menaced him from the rear. He never heard, poor lad, the warning rustle in the thicket behind him, nor saw the hungry gleam of the cruel greenish-yellow eye that glared at him through the tangled boughs; but all at once came a crackle and crash of broken twigs—a fierce yell, a stifled cry, a heavy fall—and the forest-lad lay face downward on the earth, struggling beneath the weight of a huge grey wolf, ravenous from its winter fast!

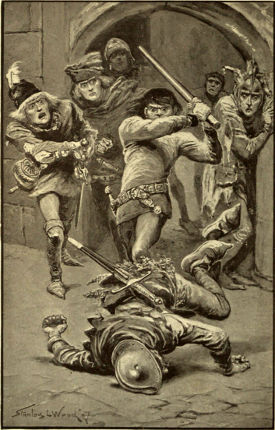

BERTRAND GRAPPLES WITH THE WOLF

Luckily for the poor boy, the furious beast was hampered for a moment by the projecting sticks of the huge fagot, on which its first rush had fallen. But an instant more would have seen the helpless lad fearfully mangled, if not killed outright, when, just as all seemed over, rescue came.

The moment the young noble caught sight of the springing monster, he looked round for the hunting-knife that he had flung down in the grass and ferns; but not finding it, he whirled up the broken bough like a flail, and dealt a crushing blow at the wolf’s head with all his might and main.

Had that blow fallen as it was meant, the brute would never have moved again; but a quick jerk of the long, gaunt body foiled the stroke, which, missing its head, hit the fore paw and snapped the bone like a reed. With a sharp howl of pain, the savage beast let go its prey and flew at its enemy.

But that sullen, hard-featured lad was one whom no peril, no matter how sudden and terrific, ever found unprepared. Dropping his now useless club, he sprang upon the wolf in turn and fastened both hands on its lean, sinewy throat with a grip like a smith’s vice.

And then began a terrible battle. Over and over rolled boy and beast, amid snapping twigs and flying dust, the boy throwing his whole force into the strangling clutch that he still maintained, while the wolf’s cruel fangs gnashed and snapped close to his throat, and its hot, foul breath came steaming in his face, and the blood-flecked foam from its gaping jaws hung upon his hair or fell in clammy flakes on his cheek.

Such a struggle, however, was too furious to last. Little by little the fire died out of the fierce yellow eyes—the wolfish yells sank into a low, gasping whine—the monster’s frantic struggles grew fainter and fainter; the victory was all but won.

But the boy-champion, too, was almost spent with the terrific strain of this death-grapple, and his numbed fingers were already beginning to relax the iron grasp which they had so sternly made good till now. One moment more would have let loose the all-but-conquered enemy, and sealed the brave lad’s doom; but just then came a flash of steel before his swimming eyes—a dull thud, like a tap on a padded door—a hoarse, gurgling gasp—and the wolf lay limp and dead on the trampled earth.

The half-witted boy, recovering from the first stun of his fall, had seen his rescuer’s peril, and his keen eye had caught the glitter of the lost knife in the fern. To pounce on it, to snatch it up, to deal one sure thrust into the wolf’s exposed side, was the work of a moment; but, quick as he was, he came only just in time.

“I thank thee, friend,” said the young noble, with a quiet dignity far beyond his years, as he slowly rose to his feet. “St. Yves be my speed, but yon blow of thine was as good a one as ever was stricken; and had it been one whit less swift or less sure, methinks it had gone hard with me. But how fares it with thee? Thou canst scarce have come off scatheless from the clutch of yon felon beast.”

“I am unharmed, messire; praise be to God and the holy saints,” said the other, respectfully. “I trow it is I who ought rather to thank your valiancy, since, but for your aid, my strength had availed nought against such a beast as this.”

“A grim quarry, in good sooth,” cried the boy-conqueror, scanning with admiring looks the slain wolf’s sinewy limbs and mighty jaws; “but, be that as it may, neither man nor beast shall harm a defenceless boy while I can lift hand to stay it!”

“It is well spoken, fair son,” said a grave, mild voice from behind; “and ever mayst thou buckler the weak against the strong, and beat down the ravening wolves that slaughter the flock of God!”

Both boys looked up with a start, and saw with surprise and secret awe that, although they had neither seen nor heard any one approach, they were no longer alone.

Beside them stood a tall, slim figure, clad in the grey frock and cowl of a monk, and protected from the flints and thorns of the rugged path only by a pair of torn and dusty sandals.

The stranger’s arms and limbs, so far as his robe left them visible, seemed wasted almost to a skeleton; and on the hollow face that looked forth from the shadowy cowl might be plainly read the traces of long hardship and bitter suffering, and of mental conflicts more exhausting than either. But on that worn face now rested the sweet and holy calmness of the peace that passeth all understanding. A kindly smile played on his thin, delicate lips, and his large, bright eyes were filled with the loving, pitying tenderness of a guardian angel, though through it pierced ever and anon a flash of keen and terrible discernment.

A child would have nestled trustfully to the owner of that face, even without knowing who he was; a ruffian or a traitor would have slunk away abashed at the first glimpse of it.

The stranger’s soundless approach, his saintly aspect, and his sudden appearance at the very moment when the death-struggle ended in victory, bred in both lads a conviction which the beliefs of that age made quite natural, and which the boy-noble was not slow to utter aloud.

“Holy father,” said he, with a low and almost timid bow, “art thou my patron saint, St. Yves of Bretagne? If so, I pray thee to accept mine unworthy thanks for thy timely aid.”

“Give thy thanks to God, my son, not to the humblest of His servants,” replied the stranger, in a clear, musical voice, “though, could my aid have profited thee, assuredly it should not have been lacking. No saint nor angel am I, but a poor brother of the monastery of Notre Dame de Secours (Our Lady of Help) in the town of Dinan; and men call me Brother Michael.”

Hardly had he spoken, when the forest-boy threw himself at his feet, and kissed his hand, crying joyfully—

“You are he, then, whom they call ‘God’s Pilgrim!’ Give me your blessing, I pray, holy father, for men say that good follows your steps wherever you go.”

“God grant the like may be said of us all!” said the monk, earnestly, as his pale, worn face lighted up with so bright and happy a smile that it fairly transfigured him for the moment. Then, laying his thin hand gently on the boy’s bowed head, he blessed him fervently.

As the overjoyed simpleton shambled to his feet again, Brother Michael turned to the boy-noble, who was eyeing him with undisguised admiration; for he too had heard the fame of “God’s Pilgrim,” who went from place to place doing good, and fearing neither pestilence, war, famine, robbers, nor any other peril, if there was even a chance of helping and comforting his fellow-men.

“Son,” said he, kindly, “I have told thee my name; wilt thou tell me thine?”

“Bertrand du Guesclin,” replied the boy, in a tone of sullen dejection, which showed that he, at least, had no guess how soon the unknown name that he uttered so despondingly was to echo like a roll of thunder through the length and breadth of Europe, and to be the symbol of all that was chivalrous and noble alike with friend and foe.

The monk started slightly, and stood silent for a moment or two, with knitted brow and compressed lips, as if trying hard to recall some half-forgotten association connected with the name that he had just heard.

“Give me thy hand,” said he at last, in a strangely altered voice.

The future hero extended his broad, sinewy hand to the clasp of Michael’s long, slender fingers; and the monk’s deep, earnest eyes rested with a penetrating glance on those of young Du Guesclin, which, as they met his, remained fixed as if unable to turn away.

So the two stood gazing at each other without a word for some moments, while the young forester looked wonderingly on.

“Give glory to God, my son, for He hath destined thee to great honour,” said the monk at last, with a solemn earnestness, which showed how deeply he felt the importance of the strange message that he was delivering. “The grace of Heaven hath vouchsafed to mine unworthy self the gift of reading in each face that I see the destiny of him who bears it; and I read in thine that God hath chosen thee to be the champion of this distressed land, and to save it from all its foes!”

To any man of that age, the voice of a Churchman was as that of God; and Bertrand no more thought of doubting the monk’s words than if they had come down to him from heaven. His heart bounded at the thought that he, the ill-favoured, the mocked, the despised—he, on whom his own parents looked down as a shame to them—should be chosen by Heaven itself for so glorious a task; and it was no disbelief, but sheer astonishment, that fettered his tongue when he tried to answer.

“I the champion of France?” said he at last, with a look and tone of joyful amazement.

“Thou and no other,” said the monk, firmly. “Why look’st thou thus amazed? Is it not told in Holy Writ how the greatest king of God’s chosen people was at the first but an unknown shepherd-lad, and how he too was despised by his own kin?”

“Ha! how know’st thou that, holy father?” cried Du Guesclin, starting.

“By the revelation of God,” said Michael, solemnly. “Fare thee well, my son; be thou strong to do thine appointed work, and to curb thine own rebellious spirit; for he that humbleth himself shall be exalted. As for thee, my child,” added he to the half-witted lad, who had watched this strange scene with ever-growing wonder, “come with me; I have somewhat to say to thee.”

The wood-boy obeyed like a child; and the next moment boy and monk vanished amid the trees, while Bertrand remained standing like a statue on the spot where they had left him, deep in thought.

The sunset of that memorable evening, as it faded from the scene of the wolf-fight, sent its last rays streaming through the small, narrow, loophole-like window of a plainly furnished upper room in Motte-Brun Castle (which stood two miles away on the edge of the wood), lighting up the face and figure of a tall, stately, grey-bearded man of middle age—whose plumed cap and rich dress showed him to be a noble—as he paced restlessly to and fro.

He was still strong and active for his years, and so markedly handsome that no one could guess him to have the unenviable renown of being father to the ugliest lad in Brittany. Yet such was the case, for this man was the Seigneur Du Guesclin himself, the lord of Motte-Brun.

The temper of a feudal lord of that age was usually anything but sweet; and Messire Yvon du Guesclin thought nothing of flinging a knife at his son or wife in the middle of dinner, or knocking out the teeth of some unlucky vassal with his sword-hilt. But, on this particular evening, his bent brows, his short, fierce step, and the very strong language that came growling through his set teeth, told that he was in an even worse temper than usual, or (as an observant man-at-arms of his poetically said) “as ill at ease as a fat friar in Lent.”

For this ill-humour, however, there was really some excuse. In the first place, Sir Yvon’s bandaged right arm showed that he was, for the present at least, disabled from taking part in the constant fights which were then so recognizedly the chief amusement of a gentleman, that when no foes were to be had, men would fight their friends just to keep their hand in. Secondly, he seemed likely to be kept waiting for dinner (no trifle to the fourteenth-century barons, who had the appetite of other wild beasts as well as their ferocity), for his wife, Lady Euphrasie du Guesclin, had not yet returned from her afternoon visit to a neighbouring convent; and though (like most gentlemen of that “chivalrous” age) the good knight would have had no scruple about laying his whip lustily over the shoulders of his lady-wife when she happened to displease him, he would never have dreamed of offering her such an affront as sitting down to dinner without her.

But the worthy knight’s third cause of complaint was of a higher and more lasting kind.

Rumours had long been afloat (vague and doubtful at first, but growing ever clearer and more defined) of an impending breach between France and England, and a renewal of that never-ending conflict which seemed to have become the recognized state of things betwixt the two warlike races. When the war did break out, the Duke of Brittany, as one of the great vassals of the French crown, must, of course, take the field for the King of France with all his Breton knights and nobles, among whom Sir Yvon du Guesclin, the representative of one of the oldest families in the Duchy, must appear with a meagre train of but thirty men-at-arms, instead of the five hundred spears that had followed his more fortunate ancestors.

Never had the stout old warrior so bitterly regretted the poverty and decay of his once formidable house; and a yet keener pang shot through his bold heart as he looked down into the courtyard from the balconied platform of the bartizan, and saw his three stalwart nephews trying their strength with blunted swords, amid the applauding murmurs of a ring of watching men-at-arms.

“Would to Heaven,” muttered the sturdy baron, clenching his unwounded hand till the knuckles grew white, “that yon brave lads were indeed mine; so should our ancient name be worthily represented. Of what sin have I been guilty, that Heaven should thus mock my prayers by giving me this black-avised abortion for my only son?”

This idea had been often in Sir Yvon’s mind (if, indeed, it could be said to be ever out of it) since he had given a home, a few years before, to his three orphan nephews, whose own home had been destroyed in one of the merciless wars of those “good old times.” All the old knight’s friends fully expected him to adopt one of the three as his son, and disinherit the unsightly Bertrand; and probably it was only the consciousness that it was so universally expected, which, acting on his native Breton obstinacy, kept him from doing it at once.

“Yonder comes my lagging dame at last,” growled the baron, as several riders issued from the wood, with a female figure in their midst; “and methinks she is in as great haste for the even-meat as I, for she rideth as if for a wager! If any churl hath dared to molest her——”

And, with a black frown on his face, the old warrior hurried down the narrow, winding stair to meet his lady’s return.

He had plenty of time to reach the inner gate ere she entered it; for in those days the admission of a lady to her own house, after even the shortest excursion outside the walls, was a work of no small time and trouble. To begin with, it was out of the question for her to venture forth at all without at least a dozen well-armed attendants clattering at her heels; and when she and her train returned, drawbridge must fall, and bolt and bar go grating back, ere she could enter her own home.

At the first glimpse of his wife’s face, as he stepped forward to aid her to dismount, the Sire du Guesclin started in spite of himself. What could it be that had broken the habitual melancholy of that sad though still beautiful face with the dawn of a new and exciting hope? So might some prisoner look, who, doomed for life to a gloomy dungeon, should be told, after long years of weary captivity, that he was a free man once more.

“Husband—husband—I have heard——” she began brokenly, and then stopped, as if unable to say more.

“What hast thou heard, dame?” cried the old baron. “No ill news, I trust?”

“No, no! joyful news; great good news of our poor Bertrand!”

“Good of him?” growled Bertrand’s father, with a scornful laugh. “When a kite becomes an eagle, then may he prove worthy of our name!”

Four centuries later, the father of another great man was as hard of belief in any good coming of his “disgrace to the family.” When he heard that his despised son had achieved a feat that filled the whole world with his renown, and changed the history of a mighty empire, his sole comment was to growl, “The booby has got something in him after all!” For the world is ever slow to recognize its greatest; and he who told the tale of the “Ugly Duckling” that grew into a swan, might have found an apt illustration of it, either in Bertrand du Guesclin or in Robert Clive.

“Nay, take it not amiss, sweetheart,” cried Sir Yvon, softening his harsh tones as he saw his lady’s face cloud at finding her great news so ill received. “Go, busk thee speedily for supper, and over the good cheer I will hear thy tale; for if it be ill talk ’twixt a full man and a fasting, ’twixt two fasting folks it must be even worse.”

Then turning to his attendants, he shouted, with the full might of a voice that made the whole castle echo—

“Ho, there! bid the knave cooks be speedy, or their skins shall smart!”

The terrified cooks knew well that this was no idle threat, and bestirred themselves so briskly that ere Lady Euphrasie had completed her toilet, the evening meal was smoking on the board.

This baronial dining-room would have greatly startled any householder of our time; for in this primitive stronghold (where the refinements that had begun to make their way in England were still unknown) the lord and lady of the castle dined in the same hall and at the same table with the soldiers of their garrison, the only difference being that the latter sat at the lower end. The ponderous rafters were literally coated with soot by the smoke, which seemed to go everywhere but up the chimney; and the rotting rushes that strewed the stone floor were crusted with mud from scores of booted feet, and littered with the bones flung to the big, hairy wolf-hounds that lay round the huge fire. The harsh voices and coarse oaths of the men-at-arms were plainly audible at the upper end of the board; and the torches that crackled and sputtered in iron cressets along the wall (adding their contribution of smoke to that which already filled the hall), kept quivering and flaring in the night-wind that whistled through the glassless windows.

In a word, the dirtiest and noisiest London tavern of our day would compare favourably, both in cleanliness and comfort, with the dining-hall of this high-born gentleman of the good old times.

“Now, dame,” said Sir Yvon at last, through a huge mouthful of roast beef, “let us hear this news of thine.”

And the lady, instinctively lowering her voice, began thus—

“The vesper-bell had not ceased when I drew bridle at the convent gate, and I went into the chapel to join my prayers with those of the holy sisters; and when prayers were over, my cousin, the Abbess, would fain have me tarry for the evening meal. But to that I said nay, for I knew thou wouldest be watching for my return.”

A kindly look thanked her from the old castellan’s keen eyes.

“But I thought it ill to depart without visiting Sister Agnes, the holiest of them all; and I craved such comfort as she could best bestow, for my heart was exceeding heavy. So I hied me up to her cell in the rock.”

Here she paused a moment, while her three nephews (who sat a little below her, in order of age) bent forward in silent attention. None of the three, however, ventured to speak, for in that age it would have been the worst possible presumption for any young man (especially if not yet made a knight) to join unasked in the talk of his elders; and the youths had seen enough of their good uncle’s surprising readiness with his hands in such cases, to find in it an effectual curb to their natural forwardness.

“Ere I passed the threshold,” went on the lady, “she called me by name, and bade me enter. As I did so, she rose from her stony seat, and took me by the hand (the like did she not for the Duchess of Brittany herself) and said, more blithely than she was ever wont to speak, ‘Welcome, thou favoured of Heaven! I am sent unto thee with glad tidings. Go tell thy lord to cease his murmuring against God for sending him a son like Bertrand; for lo! that same Bertrand shall yet be the glory of his house, and of the whole realm of France!’”

“What? what?” cried the baron, excitedly; “said she, ‘the whole realm of France’?”

“That did she,” said his wife, in a voice trembling with emotion; “those were her very words!”

The hearers exchanged looks of speechless amazement.

“And as she spake—whether it was but the echoes that answered her, or a choir of unseen angels sent to guard the holy place—methought I heard many voices repeat her words: ‘The glory of his house, and of the whole realm of France!’”

She ceased, and hid her face in her hands as if overcome by emotion.

Such prophecies were then matter of implicit faith; and those of Sister Agnes, in particular, were famed through all Brittany for their exact and often immediate fulfilment. Hence neither Bertrand’s scornful father, his desponding mother, nor his sneering cousins (utterly astounded though they all were by this prediction) had a doubt that this clumsy, ill-favoured lad of whom they were so ashamed was destined to rise above them all; but how, no one could imagine.

But ere any one could speak, a clamour of voices was heard outside, and a hurried trampling of feet.

“Ha!” cried the old baron, frowning, “who dares make such ado in my castle? By St. Yves of Bretagne, I will take some order with these roisterers, be they who they may!”

But as he sprang up to make good his threat, the hall door flew open, and in came the grey-haired gate-porter.

“Woe is me, my lord, that I should bring you evil tidings! A woodman hath come hither but now, having found in the forest Messire Bertrand’s hunting-knife lying by a slain wolf; but of my young lord himself saw he nought!”

“Oh, my son, my son!” wailed Lady Euphrasie, whose motherly heart awoke too late.

“Peace with thy whining, wench!” said her husband, angrily; “this is no time for tears and cries. Where is this woodman, fellow? Bring him hither straightway.”

A moment later a sturdy peasant, in soiled leather jerkin and leggings, slouched bashfully into the hall, and, bowing awkwardly to his lord, laid at the latter’s feet the well-known hunting-knife and the dead wolf, at whose huge carcass the old Du Guesclin (a sportsman to his very finger-tips) looked admiringly, even in the height of his anxiety and grief.

“If the boy hath done such a deed unaided, he is my true son, uncomely though he be. And methinks he is yet alive, for no wounded man could deal a blow like this; and had there been other wolves there, they could not have borne him off so clean but what some trace of him would be left. What ho! without there! Go quickly forth, knaves, some six of ye, with spear and wood-knife, and let this fellow guide ye to the spot where the wolf was slain; and whoso brings tidings of my son shall have for his guerdon as many silver pennies as he can grasp in one hand.”

The men obeyed with a will, for this sullen, ill-favoured, awkward lad, while hated and despised by his equals, had always been strangely popular with those beneath him; and there was not one of his father’s men-at-arms who would not have gladly perilled life and limb for his sake.

But this time there was no need to do either, for hardly had the searchers gone half a mile when they met the missing boy himself, and bore him home in triumph.

When Bertrand entered the hall, the expectant group started at the change that a few hours had wrought in him. Whether from the effect of the wonderful revelation made to him that day, or from the encouraging sense of having achieved a feat of which the best of those who despised him might have been proud, he seemed to have grown all at once from a rude, passionate, uncouth boy into a calm, fearless, self-reliant man. His once drooping head was now proudly erect; his heavy figure had an upright, manly bearing that half redeemed its clumsiness; and his harsh features wore a look of power and command that froze into wondering silence the jeers that rose to the lips of his handsome, scornful cousins.

The first to speak was the old knight, who, more ashamed of his momentary tenderness toward his lost son than of his former unjust harshness to him, relieved his feelings in the usual gentlemanly style of that age—with a burst of oaths worthy of a street-rough.

“Honoured father and lady mother,” said Bertrand, as he knelt to kiss the hands of his parents, seemingly not a whit discomposed by the verbal piquancy of his loving sire, “it grieves me much that ye have been ill at ease on my account. I had been here long since, had I not missed my way in the forest.”

His hearers, who had expected him to boast of having slain the wolf, or at least make some allusion to it, exchanged glances of mute surprise.

“And what of this?” asked Sir Yvon, pointing to the gaunt grey carcass on the floor.

“It was not I who slew him,” said the boy, with that innate modesty that in after years set off so strikingly the great deeds which he did. “He fell upon a half-crazed lad whom I met in the wood, and I, having let fall my knife by mischance, took him by the throat and strove to throttle him, in which grappling the boy came to my aid, and slew the beast with mine own knife.”

There was another pause of silent amazement; and perhaps even the haughty youths who listened felt a passing twinge of shame at the thought that they had been mocking and despising one who could face such a monster with his bare hands, and well-nigh master it too.

“We will hear the rest of thy tale anon,” said his father at last, “for, as the old saying goes, it is ill talk between a full man and a fasting. Ho, there, fellows, bring hither some food straightway!”

He was at once obeyed; and Bertrand, hungry as a hawk after his late battle, fell to with a will, secretly pleased to find his rigid father relaxing for once the strictness of his oft-quoted rule—

It was midnight, and all was still in the castle save the ghostly hooting of an owl from some half-ruined turret above, and the long, dreary howl of a prowling wolf from the gloomy wood below.

But Bertrand du Guesclin, tired as he was, and still as was all around him, had never felt less inclined to sleep. The yet uncooled excitement of the first life-and-death struggle in which he had ever been engaged, the wonderful and dazzling prospect opened to his fiery spirit by the mysterious prediction of that day, above all, the inspiring thought that his courage had actually been owned to some extent, however ungraciously, even by those who had hitherto despised him, pulsed through his veins like living fire, and banished all thought of slumber.

Fevered and restless, the future champion of France at length thrust his heated face through the narrow window into the cool night-air, and was watching the rising moon peep timidly above the black, whispering tree-tops, when his mother’s voice was heard below—

“Assuredly Bertrand is indeed destined to great honour, for, had but one of these two spoken it, it must needs have been truth. How much more when they are both in one tale!”

The listening boy started, and held his breath to hear. What could his mother mean by “both”?

“Thou art right, dame,” replied Sir Yvon’s harsh tones, “for St. Thomas the Doubter himself, I ween, could find in this matter no room for unbelief. Bertrand goes forth at hazard into the wood, and meets there the pilgrim monk; and he, who knoweth the future as I know the blazonry of mine own escutcheon, tells the boy that he is chosen of Heaven to be the champion of the land! On the same day, and at the same hour, thou, knowing nought of all this, goest to yonder convent; and lo! the holy Sister Agnes, in whom is the spirit of prophecy, welcomes thee as one favoured of Heaven, and gives thee joy for that Bertrand is fated to be the glory of our house and of the whole realm of France. Who shall gainsay such testimony as that?”

The boy’s heart throbbed as if it would burst; for, though he had known of his mother’s purposed visit to the convent that day, this was the first that he had heard of its result.

The strange message was confirmed, then! Twice in one day had his future greatness been foretold by tongues that could not lie; and, like his favourite hero, King David, he was singled out by the choice of God Himself to be exalted from a nameless youth into the deliverer of his people! What more could heart desire?

In the tumult of his feelings, the excited lad failed to catch his mother’s answer; but he heard plainly his father’s gruff tones in reply.

“How he is e’er to be famed in knightly arms, I see not, for he is too clumsily shapen for lance or saddle; and, moreover, with that Saracen face of his (which hath the fashion of the demons in our mystery-plays) how shall he e’er get him a lady-love? And what true knight can duly do his devoir (duty) without one?”

Again the boy missed his mother’s reply; but its purport was easy to guess from Sir Yvon’s growling rejoinder—

“Anger me not with thine ill-bodings, foolish wench. Heaven forbid that son of mine should ever be scholar or maker (poet), or any such useless vagabond! Methinks there is little fear of it, for, thank God, he can neither read nor write; so far, at least, he is a true Du Guesclin!”

Such was indeed the case, for the fourteenth-century gentleman prided himself even more on his utter ignorance of letters than his counterpart in our day on his knowledge of them.

“Moreover,” went on the worthy castellan, striving to fortify himself with every assurance against the dreaded risk of his son degenerating into an educated man, “the boy himself saith Brother Michael’s words were, ‘The champion of this land;’ and in what wise should any champion aid his land, save with hand and weapon? ’Tis not with parchment and goose-feather, I trow, that men beat back sword and lance; nor is it with musty maxims stolen from dead men that one setteth armies in array. Nay, look not downcast, sweet; I meant not to chide thee, howbeit thy words chafed my rough humour somewhat. Break we now our parle, for it waxeth late, and it is full time we were sleeping.”

And their voices died away.

Sir Yvon and his lady might have been less slow of belief could they have looked forward into the future barely the space of one long lifetime, to the day when France, in her sorest need, was to find a champion and deliverer, not in a strong and daring young noble, but in a gentle, dreamy, child-like peasant girl of Lorraine, who was destined to lead great armies to victory, capture strong cities, defeat great generals in battle after battle, and hand down to the admiration of all ages, so long as the world should last, the glorious name of Joan of Arc.

But all this was still in the unknown future; and the many perils then darkening over France might well have seemed, even to a shrewder brain than that of the rugged old Breton knight, to call for a far abler champion than a passionate, headstrong, untaught boy of fourteen.

Within the realm, the smouldering rage of the trampled peasantry against the merciless oppression of the French nobles was gathering strength year by year, and was destined to explode ere long in that terrific outbreak that ante-dated the worst horrors of the French Revolution, and made all Europe shudder at the name of the Jacquerie. Without, the fiery young English king, Edward III., was already preparing to strike the first blow of that tremendous war which was to waste the best blood of France and England for many a year after his death. And to crown all, whereas England was as one man in her eagerness for the coming strife, France was fatally divided against herself, the king against the nobles, the nobles against each other, and the trampled people against both; and even the clergy were similarly divided between two rival popes, some adhering to Pope Clement of Rome, others to Pope Benedict of Avignon.

Long did Bertrand sit musing on such rumours of these things as had come to his ears, and on the strange twofold prophecy that had marked himself as the only one who could stay the tide of ruin that was about to overwhelm his country. It was long past midnight ere he closed an eye; and even when his growing weariness overpowered him at last, the wild thoughts that had troubled his waking hours still haunted him in a dream.

He dreamed that he was making his way, slowly and painfully, through the pathless depths of a dark forest, amid which one solitary break gave him a glimpse of the walls and towers of a distant town. Suddenly rose before him the shadowy outline of a strange and monstrous shape, so dim in itself, and so faintly seen amid the gloomy twilight of the overarching trees, that he could hardly tell if it were a mighty serpent, or a long line of armed men marching in single file, till, all at once, a flash of fire sprang from what seemed to be the monster’s head, revealing in all its hideousness the form of a huge dragon, with the iron claws, vast shadowy wings, and flaming breath assigned to it by popular tradition.

Just then came riding through the terrible forest, right toward the dragon’s open jaws, a lady on a snow-white palfrey. Her garb was the usual dress of the time—a high, pointed cap, a long veil waving from it, and a flowing robe secured at the waist with an embroidered girdle; but her face was such as he had never seen before, dreaming or waking. Even its marvellous beauty was less striking than the sweet and holy calm that dwelt in every line of it, and the strange, solemn, almost prophet-like depth of earnestness in the large, lustrous eyes, which seemed to look beyond and above all the sorrows and perils of earth, with the quiet confidence of one over whom neither peril nor sorrow had power any more.

At the first glimpse of her the dragon fell writhing to the earth, and the strange maiden, leaping lightly from her horse, planted her bare foot fearlessly on the monster’s vast scaly bulk, and passed over its body unharmed, while at that moment broke from the sky overhead, in sweet music, the words of a familiar psalm—

“Thou shalt tread upon the lion and the adder; the young lion and the dragon shalt thou trample under foot.”

Just then the prostrate monster’s hideous head changed suddenly to a human visage almost as horrible—a brutal, ruffianly, soulless face, with a bristling red beard and a low, receding forehead, across which ran a broad smear of blood. For one instant the fierce eyes glared unutterably, and then became fixed and rayless, while a last shudder quivered through every ring of the mighty coils, ere they stiffened in death.

Then it seemed to Bertrand that he approached the wonder-working stranger, and strove to ask who she was, and whence she came; but his tongue was fettered, and not a word could he utter.

As he stood speechless, the dream-lady stepped up to him with a laurel wreath in her hand, and, placing it on his brow, said in a clear, musical voice—

“Hail to the champion of France!”

Instantly the words were echoed as if by an unseen multitude, in far-resounding chorus, strong and deep as the roll of a mighty sea, “Hail to the champion of France!” and, with that shout still in his ears, the dreamer started and awoke.

The later autumn of that year was already stripping the Breton woods of their leaves, and Bertrand du Guesclin’s fifteenth birthday was not far away, when a band of horsemen, twelve in number, rode into the town of Dinan, under the lowering sky of a gloomy October morning, at a flagging pace, which told that they had already ridden long and hard.

Two knights in complete armour; two stalwart esquires in plainer but as serviceable harness; a brace of handsome, smooth-faced boy-pages, barely twelve years old, lightly and daintily armed, and visibly proud of their finery; and half a dozen sturdy men-at-arms, whose weather-beaten faces and battered steel caps showed them to be no novices in war.

Such a train would have been, in that age, a scanty following for one knight, much more for two. But, small as it was, it drew much attention from the passers-by; for the dress, arms, and faces of the travellers marked them as English, and English faces and weapons, soon to be fatally familiar to the people of this quiet region, were a novelty among them as yet.

It was plain, however, that neither knights nor squires, but the two young pages, were the chief objects of attention, and certainly not without cause; for, apart from the gorgeous and somewhat foppish richness of their dress, they were as exactly alike as the twins in Shakespeare’s “Comedy of Errors.”

Both had the same ruddy complexion, the same clear-cut, delicate features, the same bright blue eyes and wavy golden hair, the same height and build, the same precociously dignified and almost haughty bearing. Their very voices were the same; and, as if to make the confusion worse, they were dressed just alike! In a word, the closest observer could not have told which was which; and as ideal twin-brothers (which was just what they were), they might have matched the famous twins whose mishaps are chronicled in a popular song—

Of the two knights, the younger seemed a brisk, comely, jovial youth, whose rather weak face told that his arm would be worth more than his head in the stirring times that were at hand. The very reverse might have been said of his companion, a tall, spare, sinewy man, with a grave and rather sombre face, which would have been handsome but for the sinister look given to it by the thin, pinched lips and small, deep-set, crafty eyes. A keen observer might have noted that, even while talking gaily with his young comrade, Sir Simon Harcourt contrived to keep a close though unobtrusive watch on his two pages, whom he ever and anon addressed as “fair nephews.”

Even before reaching the town gate the travellers met more than one startling example of the pleasant ways of that age.

On a huge tree by the wayside (whence a swarm of foul carrion birds flew screaming at their approach) hung the rotting corpse of a man, with his severed right hand nailed above him to show that he had been executed for highway robbery. Barely a hundred yards farther, a ragged, half-starved, wretched-looking creature begged alms of them in a lisping, whistling voice, fearfully explained by one glance at his disfigured face, the upper lip having been slit right up to the nostrils by the hangman’s knife—the punishment then awarded by the laws of France to “all such as speak blasphemies against God and the holy Church.”

A few minutes later a faint cry, half-drowned in a roar of savage laughter, drew their eyes to a deep, miry pool in a hollow below, in which a dozen ruffianly peasants were ducking a poor old paralytic woman on suspicion of being a witch; and as they came up to the gate they beheld another sight even more characteristic.

Just outside the gate sat a man wrapped in a long mantle of coarse grey frieze, with a heavy stick beside him; and as they were about to pass he rose and said, with a bow not at all in keeping with his rough dress—

“I pray you of your courtesy, fair sirs, to have pity on a poor sinner, and give me, each of you, as ye pass, one handsome blow with this good cudgel for the health of my soul.”

“Thou art doing penance, then?” said Harcourt, showing no surprise at a request that would have startled not a little any man of our day.

“Even as you say, Sir Knight,” replied the man in grey. “In this town, well-nigh a year agone, I did a grievous sacrilege (may the saints forgive me!) and confessed it not, nor thought more of it, making light of Heaven’s justice. But therein I erred greatly; for a sore sickness fell upon me, and, with the terror of death on my soul, I confessed my sin to a holy monk, and he appointed me this penance—that I should abide at the gate of this town, where my fault was wrought, with none other shelter than this mantle, craving a thwack from every one that went in or out, till I should have made up the full tale of three hundred stripes, according to the number of the days that passed betwixt the doing of my sin and the confessing thereof.”

“And how much lack’st thou yet of the number?” asked the younger knight.

“No more than forty and four, God be thanked,” said Grey-cloak.

“No more?” cried the young cavalier. “Nay, if that be all, I will gladly aid thee, as one Christian man should aid another, by discharging on thy shoulders, with mine own hand, the whole remaining debt.”

“I thank you humbly for your goodness, fair sir,” said the penitent, as gratefully as if the other had offered him the highest possible service; “but alack! it may not be. But one stroke may I have from each man who passeth, and all else is nought.”

“’Tis pity,” replied the young knight; “but, sith better may not be, we will do what we can. Here be some twelve of us, and we will at least help thee a dozen stripes nearer to the balancing of thine accompt.”

One by one the twelve whacks were duly administered, and then the train rode on again—the knights exchanging meaning glances, the pages tittering audibly, and the men-at-arms (who had evidently no idea of anything ludicrous in what had passed) grave as judges, while the thrashed man, as he rubbed his bruised shoulders, called after them, obviously in perfect good faith—

“May Heaven requite you for your goodness, kind sirs, and help you in your need as ye have helped me.”

Hardly had the riders entered the town when they were almost swept away by the rush of a mob of townspeople—men, women, and children—all hurrying so eagerly toward the great market-place, that they scarcely heeded Sir Simon’s inquiry to what spectacle they were thronging in such haste.

But the answer, when it did come, was amply sufficient. These eager sightseers were running to see a man put to death.

The French wit who caustically said that he had “witnessed all the public amusements of England, from the quiet cheerfulness of a funeral to the boisterous gaiety of a hanging,” might have uttered his cruel jest as sober earnest, had he lived in the “good old days” of Edward III. In that iron age, the mere sport of which was a mimicry of war in which brave men were constantly falling by the hands of their best friends or nearest kinsmen, all classes alike ran to enjoy the sight of tortures and executions, as we should now enjoy a circus or a pantomime; and crippled beggars, and mothers with babes at their breasts, would drag themselves for miles through dust or rain to see a criminal broken on the wheel or burned alive.

Thus it was now. As the knights and their train rode on through the narrow, crooked, filthy streets, the ever-growing crowd thickened around them, till at last Harcourt was fain to place at the head of the troop his three strongest men-at-arms, who cleared the way unceremoniously with their stout spear-shafts. Thus they continued to advance slowly, till a sudden turn round the corner of the great square brought the whole dreadful scene before them at once.

Just in front of the town hall, at the very spot where Bertrand du Guesclin afterwards fought his famous combat with the English champion, Thomas of Canterbury, rose like an island out of the sea of upturned faces a high wooden platform, on which, in an iron frame filled with blazing wood, stood a huge cauldron, big enough to cook an ox whole.

All around this scaffold (for such it was) glittered the weapons of a double row of halberdiers in steel caps and buff-coats, as a barrier against the surging crowd. Above them, on one side of the platform, stood the Governor of Dinan himself (a portly, middle-aged, rather stern-looking man in a suit of embroidered velvet) amid a group of richly dressed officials; and beside him was his secretary, a prim, grave man in black.

On the farther side of the scaffold, close to the now steaming cauldron (on which their eyes were fixed with a look of hungry, wolfish expectation) stood three short, sturdy, ill-looking fellows, ominously clad in blood-red shirts and hose, with their brawny arms bare to the shoulder. There was no need to ask who they were; a child would have known them at a glance for the executioner and his two assistants.

But it was neither the gaily dressed officials nor their grim satellites who drew the chief attention of the crowd. All eyes were fixed on a bare-headed, half-stripped figure just behind the men in red, with heavy fetters on its wrists and ankles. This wretched creature lay helplessly heaped together as if paralyzed by weakness, or benumbed with terror; and the deathlike paleness of his coarse face, with the fixed stare of blank, stony horror in his bloodshot eyes, would have told to the most careless observer that this was the man who was doomed to die.

“Mother, mother!” cried a young girl, who stood at a window of a tall corner-house, “hither, hither quickly! The water is nigh to the seething, and it were pity for thee to miss the sight of the punishment.”

“Thou art right, Jeanneton,” said a buxom matron, stepping up beside her, “and the better luck ours that our window looks right down on the scaffold. From hence I can see the fellow’s very face (and marry! ’tis as pale as a spectre!) at mine ease, without being trampled in yon crowd as one treads grapes in the vintage.”

Just then the blast of a trumpet echoed through the still air, and a fantastically dressed man, stepping to the front of the platform, made proclamation as follows:—

“Oyez, oyez, oyez (hearken)! Hereby let all men know that forasmuch as Pierre Cochard, of the town of Dinan-le-Sauveur, in the bishopric of St. Malo, hath been found guilty of sundry crimes and misdeeds, and notably of clipping and debasing the coin of our lord the king, therefore hath the king’s grace ordained, of his great clemency and justice, that even as the said Pierre Cochard hath melted and defaced the good and lawful coin of this realm, so shall he be himself melted and defaced in like fashion, till no trace of him remain; to wit, that he die by water and by fire, being plunged into yon cauldron, and therein boiled alive. God save the king!”

Of all the countless listeners, not one had the least perception of the horrible irony that lurked in this prayer to the God of mercy for the welfare of a king who could doom his fellow-men to a death like this. All they saw in the whole affair was a rogue receiving his due; nor could far more civilized ages triumph over them on that score, since, as much as three centuries later, seven men were hanged and a woman burned for the same offence in England itself.

When the herald’s voice had died away, there sank over that great multitude a dead hush of terrible expectation, amid which the executioner’s harsh tones were plainly heard to the farthest corner of the square, as he said to the governor, with a clumsy obeisance—

“My lord, the water boils, and all is ready!”

At the words, as if that dread signal had broken the spell that paralyzed him, the doomed man sprang to his feet with a long, wild scream of mortal agony, so terrific that even the brutal mob shuddered as they heard it.

But the executioner and his mates, to whom such horrors were a mere everyday matter, remained wholly unmoved, and advanced to their fell work with perfect unconcern. Already they had clutched the victim to hurl him into the boiling cauldron, when his eyes, as they wandered despairingly over the unpitying crowd below, lighted up with a sudden flash of recognition, and, wrenching himself with a mighty effort from the grasp of his tormentors, he flung out his fettered arms wildly, and shrieked, in tones more like the yell of a wounded wild beast than a human voice—

“Brother Michael! Pilgrim of God! save me, save me!”

“Who calls me?” replied a clear, commanding voice from the other side of the square. “If any man need mine aid, I am here.”

At the same instant the crowd, close-packed as it was, parted like water, and through it came the mysterious monk whom Bertrand du Guesclin had met in the wood seven months before.

As he came up the steps of the scaffold, it was strange to see how all the actors in that horrible drama, from the pompous, self-important governor down to the brutal, soulless headsman, shrank from his look, and cast down their eyes as if detected in some shameful misdeed. True, they were only obeying the law; but perhaps, in the presence of this higher and purer nature, even these bigoted upholders of a law that was itself a fouler crime than any that it punished had, for one moment, some dim perception of a truth that the world has always been slow to learn—viz. that to treat men like wild beasts is hardly the way to make them better.

“Yon grey friar is a man,” said one of Sir Simon’s pages approvingly to the other, little dreaming how strangely he and Brother Michael were one day to come in contact. “Mark you, brother, how boldly he stands up in the midst, and how one and all give way to him? There was a good soldier lost to France, methinks, when he donned frock and cowl.”

And his brother fully agreed with him.

As soon as the pilgrim-monk was seen to mount the scaffold, he at once became the leading figure of this grim tableau, casting all others into the shade. The stately governor, the richly attired officers, the ranks of helmeted spearmen, dwindled into mere accessories, and all eyes were fixed in breathless expectation on the solitary monk himself.

“Peace be with ye, my children,” said he, in a voice which, low and gentle as it was, was heard over the whole square amid that tomb-like silence. “What man called to me for aid but now? and what is this that ye do here?”

For the first time in his life the worthy governor found some difficulty (to his own great amazement) in saying plainly that he was about to torture a man to death in the name of justice. But the ghastly accessories of the scene spoke for themselves, and a few words sufficed to put Brother Michael in possession of the whole case.

“What ill-luck brought him here?” growled a savage-looking fellow in the crowd, as he marked and rightly interpreted the effect of the monk’s sudden intervention. “What if he plead for this dog’s pardon, and so lose us the sport of seeing the rogue die, after all?”

“Hush, for thy life, Gaspard!” muttered tremulously the man to whom he spoke. “Know’st thou not that yon monk hath such power as had the blessed saints of old, and that, had he heard these sacrilegious words of thine, it had cost him but the lifting of his finger to smite thee with palsy where thou standest? Heed well thy tongue, I counsel thee, lest it be withered betwixt thy jaws.”

Meanwhile the governor and his officers had fallen back to one side of the scaffold, and the three executioners to the other, leaving monk and criminal alone in the midst.

“Art thou guilty of what they lay to thy charge, my son?” asked Michael, bending over the prisoner, who was grovelling at his feet and clinging to them with the frantic energy of utter desperation.

“I am, I am!” moaned the doomed wretch, looking up at him imploringly. “But thou canst save me if thou wilt.”

“Even so spake the leper unto our Lord Himself,” said the monk, with a strange smile on his worn face; “and as he said, so it was done to him.”

Then he turned to the officials with a look so solemn and commanding, that to their startled eyes his slight form seemed to grow larger as they gazed.

“Hearken, my sons. Ye know that to me, all unworthy as I am, hath been given power to claim a man’s life from the law when fit cause shall appear. Now, methinks it were better for this man to live and repent than to be cut off in his sins, wherefore I claim him as the Church’s prisoner.”

In that age and that region there could be but one answer to such a claim, especially when made by one who was held to be little, if at all, less than a saint himself; and though the governor flushed angrily at this trespass on his privilege of destruction, and the hangman scowled sullenly to see his prey snatched from him, no one dared to object.

“He is thine,” said the governor, sulkily. “Clerk, make entry to that effect.”

But the scratching of the clerk’s ready pen on the parchment was suddenly drowned by the thud of a heavy fall, as the rescued criminal, unable to sustain the terrific shock of this unexpected deliverance, fell down in a fit.

He recovered, however, to live long and peacefully in the monastery where his rescuer placed him, extolled by its prior as the best of his lay-servants. But that day’s vision of death had been too close and too ghastly for its influence ever to pass wholly away; and to the end of his days, he could never hear, without shuddering and swooning, the hiss and bubble of boiling water.

“Now, beshrew these darksome woods, with ne’er a path through them! I had rather (so help me good St. George of England!) be set to find my way through yon Maze of Woodstock, of which the ballad-makers tell.”

“Right, comrade. And methinks these thickets, where twenty men might lie in ambush unseen within a spear’s length of us, are a choice chapel for the clerks of St. Nicholas” (i.e. robbers).

“Nay, if that were all, I care not, for even a passing brush with forest-thieves or outlaws were better than no fight at all; and I trow the lasses in merry Hampshire will hold us cheap when they hear that we have come oversea without one fight to rub the rust off our weapons. But, if all tales be true” (the speaker sank his voice to an awe-stricken whisper), “there be worse things than thieves in these woods.”

“Not a word of that, lad, an’ thou lov’st me. There is a time and a place for all things, as good Father Gregory was wont to say; and this” (casting a nervous glance over his shoulder into the deepening gloom around) “is neither the time nor the place, I trow, for tales of sprites and hobgoblins.”

Thus muttered Sir Simon Harcourt’s men-at-arms as they struggled wearily through the wood that had witnessed Bertrand du Guesclin’s wolf-fight, on the third evening after their departure from Dinan. But in exercising so freely an Englishman’s natural privilege of grumbling, the stout Hampshire yeomen were by no means without excuse.

They had been forcing their way for more than an hour through the tangled thickets of a gloomy and almost pathless wood, without ever coming any nearer, so far as they could see, either to getting clear of that dismal maze or reaching the town of Rennes, where they meant to spend the night. Then, darkness was coming on fast, menacing them with the far from agreeable prospect of wandering in the woods all night long; and last, but certainly not least, the huge black storm-cloud that was blotting out the red and angry sunset betokened the approach of such a tempest as even the hardy English would not willingly have faced unsheltered.

“’Tis not for myself I care,” said one of them; “shame on the man who makes moan like a child over a wet jerkin or an empty stomach. But my young lords are not ripe yet for hungry days and wet nights, and I ever deemed that his worship, Sir Simon, did not well to bring them hither.”

He glanced pityingly as he spoke at the slim forms of the two boy-pages.

“Why say’st thou so, Dickon?” cried another man. “Surely ’tis well for a bold lad to see the world a bit, in place of being mewed up at home like a caged singing-bird!”

“Ay, but how if the bold lad fall sick and die, through being not yet strong enow for such rough work?”

“Dickon is right,” chimed in an older man. “My young lords (God bless them both!) are full young yet for open field and hard fare; and methinks,” he added in a cautious undertone, “their loving uncle yonder would not be too sorely grieved, were it to befall them as Dickon hath said!”

“What say’st thou?” asked three or four voices at once, in tones of dismay.

“Know ye not he is the next heir after their death?” said the veteran, with grim significance. “Didst ever hear yon ballad of the ‘Babes in the Wood’?”

“Why, comrade, thou canst not mean, surely——”

“Nay, I mean nought. A man may speak of a good ballad, and no harm done.”

But the old soldier’s gloomy hints had left their mark, and thenceforth he and his comrades rode on in sombre silence.

Meanwhile the two knights who headed the train were in no blither mood.

“St. Edward! ’tis as if we were in one of the enchanted woods whereof romances tell, in which a man may wander for ever, and ne’er get one foot from his starting-place!” cried the younger man, impatiently. “My mind misgives me, Sir Simon, that we have gone much astray.”

“In sooth, I fear we have; yet methinks we did our best to follow such directions as we got in yon village, if indeed we rightly understood them, for this peasant-jargon is right hard to interpret.”

“I would I could meet one of these same peasants now, be his jargon what it might; for how shall we ask our way, if there be no man here of whom to ask it?”

“Nay, methinks I espy a man now, in the shadow of yon trees. Let us hail him. What ho, friend! are we yet nigh to Rennes?”

“To Rennes?” echoed the stranger, in a tone of amazement. “Alack, noble sirs, ye be much astray. Ye have been making straight away from the town, and were ye to turn your steeds this moment, two long leagues, and more, must ye ride to reach it.”

The younger knight growled something that did not sound like a blessing, and the rough English yeomen relieved their overwrought feelings with a burst of hearty English maledictions on Brittany, its woods, its people, and all belonging to it.

“Two leagues!” repeated Sir Simon; “the storm would be on us ere we were halfway. Hark ye, fellow, is there no dwelling near, where we may find shelter for the night?”

“Surely, noble sir; not a quarter of a league hence lieth the castle of Messire Yvon du Guesclin, who will make your worships right welcome.”

“That is good hearing,” said the younger knight, more cheerily. “Guide us thither, good fellow, and thou shalt have a silver mark for thy pains.”

“Gramercy for thy kindness, good Sir Knight; that will I do blithely,” said the man, eager to seize the chance of earning more money in half an hour than he had often made in a month. “Be pleased to follow me.”

Piloted by their new guide, the travellers soon got clear of these perplexing woods, and ere long saw before them, looming dimly through the fast-falling darkness of night, the shadowy outline of a high tower, from which, as they advanced, came faintly to their ears a clamour of loud and angry voices, a trampling of feet, the clatter of blows, and the ring of steel.

“We are in luck!” cried the younger knight, joyfully. “They are fighting within, and we are just in time, the saints be praised, for our share of the sport!”

Knights, squires, and pages loosened their swords in the sheath with a business-like and cheerful air; for, to any man of those rough times, the mere fact that a fight was going on anywhere within reach was a good reason for joining in, without caring a straw what was the cause of quarrel, or on which side lay the right.

But, to explain this tumult, we must go back a little.

Four or five of the Du Guesclin men-at-arms were lounging about the castle-yard of Motte-Brun, on their return from escorting their lady on another visit to the convent, when there came gliding among them, with a half-tripping, half-sliding step, a pale, meagre, flighty-looking man, whose fantastic dress, and parti-coloured cap adorned with small bells, showed him to be one of those nondescript personages, half idiot and half jester, who led, in the households of the gentry of that age, the life of a spaniel in a lion’s cage—now taking liberties with their masters of which no one else would have dared to dream, and now being scourged till the blood ran down, when one of those liberties happened to be ill received.

“Ha! why wentest not thou forth with us, Messire Roland?” cried one of the soldiers to the jester, whom his master had named in joke after the famous legendary champion of Charlemagne. “Had we been beset by thieves, we had sorely missed the aid of thy puissant arm.”

“Not so,” said Roland; “had ye been bare-headed, ye were safe enow without aid of mine, for never was blade forged in Brittany that could hew through skulls as thick as yours!”

A hoarse laugh applauded the retort, such as it was.

“Well, better a thick skull than an empty one, methinks,” chuckled another of the band, with a meaning leer at the jester.

“Mock me not, slave!” cried Roland, majestically, “or I will hold thee so fast that thou shalt gladly pay ransom to get free again.”

“Thou?” said the brawny, red-bearded giant whom he addressed, eyeing his challenger’s puny frame with a look of scorn.

“Even I,” replied the buffoon, solemnly. “Think’st thou that because I am weak in body, I cannot be strong in magic? I promise thee, on the faith of a madman, I will pin thee as fast as yon Paynim baron of old time, Seigneur Theseus, who was set so fast in the stocks in purgatory, that when the good knight, Sir Hercules, tore him away by main force, his legs were left behind. Sit thee down here, and mark what shall come to pass.”

The big man sat down, as bidden, on a low stone bench by the wall, and folded his huge arms with an air of defiance.

“Abracadabra!” shouted the jester, flourishing his hands within an inch of the soldier’s nose. “The spell is spoken: rise if thou canst!”

The giant, with a scornful laugh, attempted to do so; but just behind him projected from the wall a strong iron hook, which (as the crafty jester had foreseen) caught the upper edge of his steel backplate as he tried to rise, and held him down as firmly as if he were nailed to the spot!

Scared out of his wits by this strange and sudden bewitchment, the unlucky man roared like a bull, making the air ring with howls for help, fragments of half-forgotten prayers, broad Breton oaths, and vows to every saint whose name he could recollect. Meanwhile the other men (who saw at once the real cause of his strange paralysis) danced round him in ecstasy, and gave vent to roar after roar of such boisterous laughter as seemed to shake the very tower above them.

“Art thou convinced now, unhappy boaster?” said the buffoon, in a tone of condescending pity, calculated to drive the big spearman stark mad. “What ransom wilt thou pay to be freed?”

“I have but three silver groats,” gasped the victim; “take them, and free me.”

“So be it!” said Roland, with the air of a king pardoning a peasant; and, pocketing the money, he laid his hands on the giant’s shoulders, bent him down till he was freed from the hook, and said impressively, “Rise!”

The spell-bound man sprang up like a captive bursting from his dungeon, and turning hastily round, caught sight of the hook.

One glance at it, coupled with a fresh roar of laughter from his comrades, told him the whole story. With a howl like a speared wolf, he flew at the jester’s throat; but Roland, fully prepared, vanished ghost-like into the dark archway of the nearest door.

Poor Roland’s escape, however, was a case of “out of the frying-pan into the fire;” for, as he darted into the doorway, he came like a battering-ram against Alain de St. Yvon himself (the eldest of Bertrand’s three overbearing cousins, who was just coming out to learn the cause of all this uproar), driving his head into the young noble’s chest with such force as to hurl him back against the wall.

“Base-born dog!” roared the enraged Alain, in the courteous style usual with gentlemen to their inferiors in that “chivalrous” age, “I will teach thee to thrust thy vile carcass in my way! Ho there, fellows! seize this cur, and scourge him till his hide be as tattered as his wits!”

The men-at-arms (with whom the poor jester was a prime favourite) were unwillingly advancing to obey, when a voice broke in from behind, deep and menacing as the roll of distant thunder—

“Who dare talk of scourging my father’s servant in his own castle, without leave given or asked? Let any man lift a hand on him, and he shall have to do with me!”

There, in the midst of them, stood Bertrand du Guesclin, with his swarthy face all aglow, and his small, deep-set eyes flaming like live coals.

For a moment Alain himself stood aghast, for never till now had his despised cousin asserted himself like this; and his two brothers, Raoul and Huon (who had just come upon the scene), were equally astounded. There was a brief pause of indecision, and then the young bully’s native insolence broke forth anew.

“Who bade thee interfere, thou mis-shapen cub?” cried he, fiercely. “Thou shalt see thy brother-fool get his deserts forthwith, and all the more because thou pleadest for him. Ho, Charlot! give yon whining cur a taste of thy whip.”

The man he addressed (a thickset, savage-looking groom that he had brought with him to the castle) stepped forward with a grin of cruel glee on his coarse, low-browed face; but as he neared his victim, young Du Guesclin threw himself between, and grimly motioned him back.

“An thou lov’st thy life, forbear!” said he, in the low, stern tone of one who fully meant what he said; “I will not warn thee twice.”

Had the fellow been in his right senses, one glance at Bertrand’s face would have been warning enough. But he was rarely sober at that time of day, and all his natural insolence was aroused by this challenge from one whom he had always looked upon as a mere cipher in the household.

“Big words break no bones!” said he jeeringly, as he stretched his hand to seize the cowering jester.

Not a word said Bertrand in reply; but he caught up a stout pole that lay near, and brought it down like a thunderbolt full on the ruffian’s head. But that his cap was a thick one, and the skull beneath it thicker still, the cowardly rascal would never have struck a helpless man again; even as it was, he fell like a log, and lay senseless on the pavement, with the blood gushing from his mouth and nose.

Alain, now fairly beside himself with fury, sputtered out a curse too frightful to be written down, and flew at his cousin, sword in hand.

Down came the pole once more, breaking off the sword-blade close to the hilt, and snapping like a reed with the force of the blow. In another moment, Bertrand found himself in the grasp of all three brothers at once.

And then began such a struggle as the oldest soldier there had never seen. Roused to the utmost by his cousin’s insolent cruelty, and by that noble impulse to protect the helpless which was the mainspring of his whole life, Bertrand dragged the three stalwart youths hither and thither like children, and more than once well-nigh mastered all three together. Huon’s arm was crushed against a sharp corner, and bruised from wrist to elbow; Raoul got a black eye from a projecting spout; and Alain himself, with his gay clothes almost torn from his back, and his throat purple from the clutch of Bertrand’s iron fingers, had good cause to repent of his bullying. At last all four came down in a confused heap, young Du Guesclin undermost.

The three young men scrambled slowly to their feet again, torn, bruised, and aching from top to toe; but their ill-starred cousin remained lying where he had fallen, with the blood streaming over his face.

“What means this?” roared a tremendous voice amid the terrified silence that followed. “Is my castle a village tavern, that men should brawl in it?”