Project Gutenberg's The Pioneer Boys of the Yellowstone, by Harrison Adams

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Pioneer Boys of the Yellowstone

or Lost in the Land of Wonders

Author: Harrison Adams

Illustrator: Walter S. Rogers

Release Date: September 7, 2014 [EBook #46798]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PIONEER BOYS OF YELLOWSTONE ***

Produced by Beth Baran, Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

BY HARRISON ADAMS

ILLUSTRATED

| THE PIONEER BOYS OF THE OHIO, | |

| Or: Clearing the Wilderness | $1.25 |

| THE PIONEER BOYS ON THE GREAT LAKES, | |

| Or: On the Trail of the Iroquois | 1.25 |

| THE PIONEER BOYS OF THE MISSISSIPPI, | |

| Or: The Homestead in the Wilderness | 1.25 |

| THE PIONEER BOYS OF THE MISSOURI, | |

| Or: In the Country of the Sioux | 1.25 |

| THE PIONEER BOYS OF THE YELLOWSTONE, | |

| Or: Lost in the Land of Wonders | 1.25 |

Other Volumes in Preparation

THE PAGE COMPANY

53 Beacon Street Boston, Mass.

Illustrated by

WALTER S. ROGERS

Copyright, 1915, by

The Page Company

——

All rights reserved

——

First Impression,

June, 1915

PRINTED BY

THE COLONIAL PRESS

C. H. SIMONDS & CO.

BOSTON, U. S. A.

Dear Boys:—

In my last story, the title of which was “The Pioneer Boys of Missouri,” I half-promised that later on I might continue the recital of Dick and Roger Armstrong’s fortunes, and carry them further along their pathway toward the far-distant Pacific. The opportunity to redeem that promise having been given to me, I gladly meet you once more in these pages; and I trust this story will afford you quite as much pleasure in the reading as I have taken in the writing.

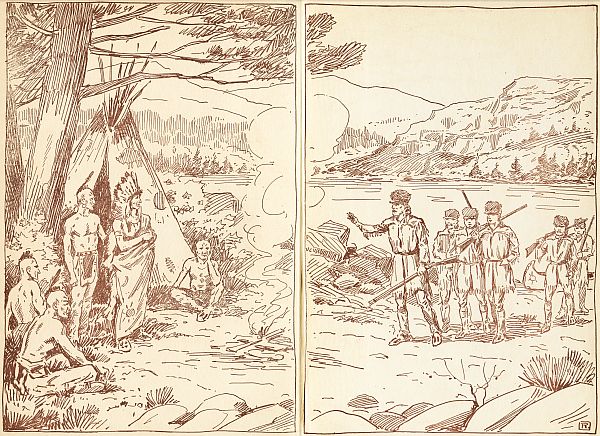

It will be remembered that we left the two pioneer lads in the winter camp of the Lewis and Clark exploring party. This company had been sent out, chiefly through the personal influence of the President at Washington, to find a way across the newly-acquired country, and blaze a path to the Pacific. They had gone into camp close to the quaint Mandan Indian village, far up on the Yellowstone River, which stream[vi] they had been following since leaving the Missouri.

Apparently their troubles and difficulties had all been smoothed away, and there seemed to be clear sailing ahead for Dick and his cousin. They anticipated spending the long winter months in various ways—studying Indian character and habits, doing more or less hunting and trapping, and possibly learning if there could be any real truth in the strange stories they had heard from numerous sources concerning a Land of Enchantment that existed near the “Big Water” at the source of the river of the yellow rocks and the troubled current.

Unexpected developments, it chanced, caused the boys to venture into this unknown and mysterious region, where they met with many adventures which I have endeavored to narrate in this volume. It will be seen that, although the various tribes of Indians inhabiting the Great Northwest country at that time undoubtedly knew of the marvels embraced in what is now Yellowstone Park, a superstitious feeling of awe for the Evil Spirit’s workings made their visits to that region few and far between, though their love for the chase did take them there at times.

I trust that if any of you ever get a chance[vii] to visit this National Reservation you will do so. And if you read the history of Yellowstone Park you will find that perhaps the first authentic account of its astonishing wonders was given to the world by a member of the Lewis and Clark expedition.

April 1, 1915.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PAGE | |

“Some of the braves started to fasten the prisoners to two trees” (See page 219) |

Frontispiece |

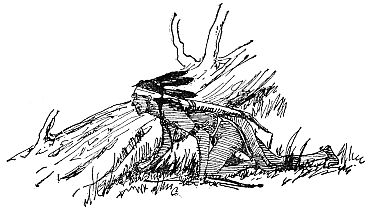

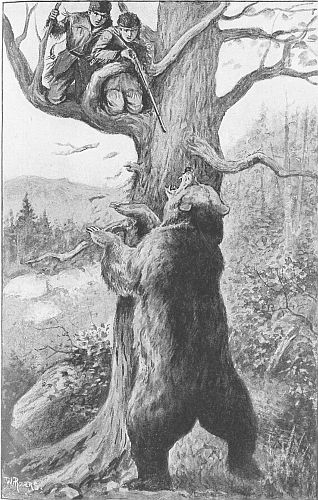

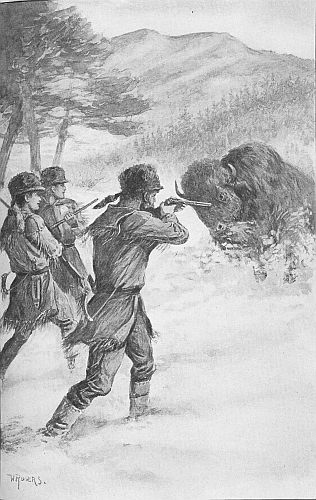

“His trembling finger suddenly pressed the trigger” |

23 |

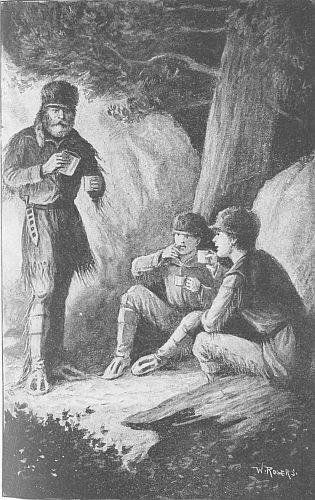

“Meager though that supper may have been, there was not a word of complaint” |

68 |

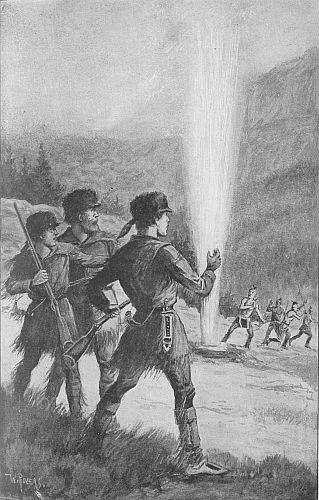

“Before them they saw a mighty column of steaming water” |

126 |

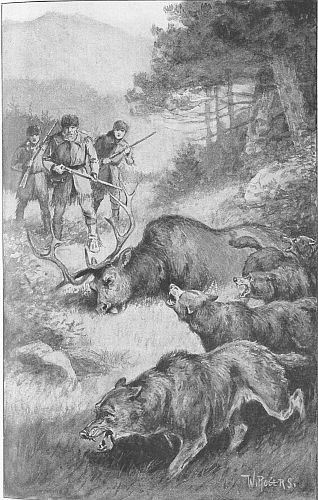

“Turning around from time to time as though half inclined to come back” |

175 |

“The buffalo was just in the act of turning when the frontiersman fired” |

294 |

“I think we have gone far enough from the camp, Roger.”

“Just as you say, Dick. I never seem to know when to stop, once I get started.”

“And it’s easy to start you, too. That was why the boys, back at the settlement of St. Louis, came to call you ‘Headstrong Roger.’”

“Well, Dick, I hope to outgrow that fault in time. You know my father was the same way, when he and Uncle Bob used to hunt and trap and fish on the Ohio River, and later along the Mississippi.”

“It seems hard to believe, Roger, that we are so far from our homes. Sometimes I shut my eyes and can picture all the dear ones again—father,[2] mother, and my younger brother, Sam.”

“Yes, but here we are, hundreds and hundreds of miles from them, and in the heart of the Western wilderness,” said the boy who had been called Roger; “and planning to spend the coming winter with our good friends Captain Lewis and Captain Clark.”

“Sometimes,” remarked his companion, “I am sorry we determined to stay here and winter near the Mandan Indian village. We might have turned back and gone home, along with the messengers who were dispatched with documents for the President at Washington.”

“And who also carried the precious paper that Jasper Williams signed, which will save our parents’ homes from being taken away from them by that scheming French trader, Lascelles.”

“And yet,” observed Dick, thoughtfully, “when I think of the wonderful things we have seen, and what a glorious chance we have of setting eyes on the great Pacific Ocean next summer, I am glad we decided to stay up here on this strange river of the wilderness that in the Indian tongue means Yellowstone.”

“It is a different stream from the ‘Big[3] Muddy’ or the Missouri, and as full of rapids as it can be. Before long the expedition will have to abandon all boats, and trust to the horses to carry the camp outfit over the mountains to the west.”

“Listen, Roger, what was that sound?”

“I thought it was the whinny of a horse,” replied the impetuous one of the pair, as they dropped behind some brush that grew on the brow of a gradual slope leading to a lower level.

“And it came from below us, too. What could a horse be doing here? Do you think any of our men are out after fresh meat to-day?”

“There are a few horses among some of the Indian tribes around here, and it might be—there, look, something is coming yonder, Dick!”

“Don’t move again, Roger; it is an Indian brave, and there follows another, treading in his trail.”

“They are not of our friends, the Mandans, Dick, and they don’t look like the Sioux we met a while ago. There come three more, and now I can see the horse!”

“H’sh! Not a whisper now, and lie as still as a rock. They have sharp eyes, even if they are not on the warpath.”

Roger knew why his cousin made this last remark,[4] for the horse was dragging two poles after him, the ends of which trailed on the ground. Upon this primitive wagon rested quite a pile of stuff, evidently the skin teepee of the family and other articles, as well as a buxom squaw and a small papoose.

Back of the first horse came a second, similarly equipped, and then another tall, half-naked brave, armed with bow and arrows. Dick knew that the little procession was a portion of some Indian community moving their camp to a place where the game would be more abundant, for this was the season when they laid in their winter store of jerked venison or “pemmican.”

“Don’t move yet, Roger,” whispered Dick, after the last figure had gone some little distance along the trail; “I believe there is another party coming. Yes, I can already see them a little way back there. Just crouch down and watch.”

While the two boys are lying hidden, and waiting for the passage of the hostile Indians, belonging to some tribe with which they hitherto had had no dealings, we might take advantage of the opportunity to ascertain just who Dick and Roger Armstrong are, and what[5] they could be doing in this unknown region, far back in 1804, when the headwaters of the Missouri had never been fully explored by any white man.

Many years previous to this time their grandfather, David Armstrong, had emigrated from Virginia to the banks of the Ohio, being tempted to take this step because of wonderful stories concerning that country told to him by his good friend, the famous pioneer, Daniel Boone.

His family consisted of three children, a girl and two boys, Bob and Sandy. The brothers grew up versed in woods lore, as did all border boys. They knew all about the secrets of the great forest and the mighty waters. And, indeed, in those days, with peril constantly hovering over their heads, it was essential that boys should learn how to handle a rifle as soon as they could lift one of the long-barreled weapons to their shoulder.[1]

Later, the pioneer was tempted to continue still further into the Golden West, always with the rainbow of promise luring him onward toward the setting sun. With other families, the Armstrongs drifted down the beautiful Ohio,[6] and finally settled on the Missouri, above the trading post of St. Louis.

Here the two sturdy lads grew to manhood, married, and built cabins of their own, near that of old David and his wife. To Bob came two boys, Dick and Sam; while his brother had a son, Roger, and a sweet girl named Mary, after her grandmother.

These two cousins, Dick and Roger, hunted in company, and were as fond of one another as their fathers had been. Dick was a little the older, and acted as a sort of safety valve upon the more impulsive Roger; but both learned the lessons of Nature, day by day, until, at the time we make their acquaintance in this volume, they were capable of meeting the craftiness of the Indian, or the fury of the forest wild beast, with equal cunning.

On the previous spring there had fallen a bombshell into the happy homes of the Armstrongs near the thriving settlement named after the French king. When David, on his arrival years before, had purchased a large section of land that was bound to grow very valuable for his heirs in later years, he had believed his title to be clear and unquestioned.

Later, it turned out that a certain signature[7] was lacking to make the title valid, and unless this could be obtained within a certain time from an heir of the original owners, the entire tract would be taken from them. An unscrupulous French trader, named François Lascelles, had secured the opposing claim, and threatened to evict the Armstrongs in the coming spring, unless they could produce that valuable signature.

This impending family trouble affected Dick and Roger greatly. They began to make investigations and learned that the man whose signature was wanted, Jasper Williams by name, a hunter and trapper, was then far away in the unknown regions of the West.

They also learned that this forest ranger expected to join an exploring party headed by two men who had recently been in St. Louis, and whom they had met in company with their grandfather, David Armstrong. These were Captain Lewis and Captain Clark, sent out by the President of the United States to learn what lay far beyond the Mississippi Valley, and possibly to proceed all the way to the Pacific Ocean, which was known to lie hundreds, perhaps thousands of miles west of the Mississippi Valley. (Note 1.)[2]

So, determined to do everything in their power to get that paper signed by the one man whose name would save their homes, Dick and Roger had finally gained the consent of their parents to their making the perilous trip.

Many weary weeks the boys followed after the expedition, which had had quite a start ahead of them. They met with strange vicissitudes and wonderful adventures by the way, yet through it all their courage and grim determination carried them safely, so that in the end they finally reached the little company of bold spirits forging ahead through this unknown land.[3]

They were received with kindness by the two captains, who admired the spirit that had brought these lads through so many difficulties.

In the end the valuable signature was attached to the paper, which was placed in charge of a special messenger whom Captain Lewis was sending, with two other men, to carry reports of the progress of the expedition to the President, who had great faith in the enterprise.

This messenger had instructions to proceed straight to St. Louis, first of all, and deliver the document to David Armstrong before heading for Washington.

The boys had yielded to the invitation of their new friends to remain with the expedition in camp through the approaching winter, and continue on in the spring to the great ocean that all believed lay beyond the mountain barrier. Such a chance would never come to them again in all their lives. The document would reach the hands of the home folks in due time, and also the letters they had dispatched with it.

And so it is that we find Dick and Roger off on a little exploring trip on a day when the chill winds told of the winter that was soon to wrap all the land in an icy mantle.

They huddled there in security behind the thick brush, and, by peeping through little openings, could watch all that went on below them. The moving Indians interested them greatly, because they apparently belonged to a tribe with which the boys, until then, had had no intercourse; although Dick guessed, from the style of head-dress of the warriors, that in all probability they were Blackfeet, and not Crows.

At any rate, he did not like their looks, and felt that it would be a serious thing for himself and his companion if by any accident they attracted the attention of the passing party. Even if they were not just then on the warpath,[10] they possessed arms, and might consider a white intruder on their hunting grounds as a bitter enemy, who should be exterminated at any cost.

The second detachment had now come along and was passing by. It consisted of several braves, and another horse dragging the poles upon which a squaw and three dark-faced Indian papooses sat amidst the camp equipage.

Suddenly Roger, in his eagerness to see a little better, when something especially attracted his attention, chanced to make a hasty move, with the result that he dislodged quite a good-sized stone, which started down the slope, gathering speed as it went.

At first, the stone seemed satisfied to merely slide downward, so that Dick hoped it would lodge in some crevice and not be noticed by any of the passing Indians. This hope was short-lived, however, for, gaining momentum as the slope grew steeper, the stone began to skip and jump, until, bursting through a little patch of dead grass, it attracted the attention of the nearest brave.

Dick heard him utter a guttural exclamation, and, at the same time saw him hastily reach for his bow, which was slung over his shoulder. The others, too, manifested immediate interest in the bounding stone, for such things do not roll down a slope without some cause and there were red enemies of their tribe who often lay in hiding to attack them.

Roger gave a gasp of dismay. That was not the first time he had been guilty of bringing some sort of trouble upon the heads of himself and his cousin. Dick laid his hand on the arm[12] of the impetuous one, and his low-whispered “Be still” doubtless prevented Roger from making matters worse by showing himself above the bush that sheltered them.

It would seem as though some good cherub aloft must have interposed to save the two lads from the peril which confronted them. Even as they lay there and stared, they saw one of the Indians point at something a little further along the slope, and then, strange to say, the procession again resumed its forward movement, as though all suspicion had been allayed.

Roger was almost bursting with curiosity to know what had intervened. He had not been able to see, because Dick chanced to be on that side of him and, much as he wanted to stretch his neck and look, he dared not attempt it after what had happened.

Accordingly they lay perfectly still until the last of the Indians had disappeared in the distance. Even then Dick would not start to leave their hiding place until absolutely sure no others were coming along the trail.

Unable to longer restrain the overpowering curiosity that gripped him, Roger presently put the question that was burning on his tongue.

“What was it happened to make them pass[13] by, and not start up here to see how that stone started to roll down?” he asked.

“Then you didn’t see the jack-rabbit, Roger?”

“A rabbit, you say, Dick?”

“Yes. It was the most fortunate thing that could have happened for us, and we ought to be thankful to the little beast that he took it in his head to skip out when that stone jumped through the patch of dead grass where he was hiding.”

“Oh! was that what happened?” exclaimed the other boy, chuckling now because of the lucky event. “And, of course, when the Indians saw the rabbit running off, they believed it had started the stone to falling. It sometimes seems to me as if we were guarded by some invisible power, we have so many wonderful escapes!”

“It may be that we are, Roger, because we know that not a day passes but that our mothers, far away down the Missouri, are praying that we may be spared to come back to them. But, now that the coast is clear, let us head once more for Fort Mandan, as we call our camp.”

Of course both these wide-awake lads knew how to find their way through the densest woods, or over unknown ground, by using their knowledge of woodcraft to tell them the cardinal points of the compass.

When the sky was clear, they could find the north by means of the sun, moon, or some of the stars. If clouds obscured their vision, they knew how to discover the same fact through the moss on the trees, or even the thickness of the bark. Besides the methods mentioned, there were others that experience and association with other rovers of the woods had taught them.

Consequently, although they might be traversing country that neither of them had ever set eyes on before, they always knew just which way to head in order to reach camp.

Dick was constantly taking mental notes as he went along. These included not only the prospects for game, but the lay of the land, for Captain Lewis wished to know all that was possible about such things before once more starting out in the spring to complete his great trip to the Western Sea.

At the same time, Dick was also on the alert for every sign of danger, from whatever source. His keen vision took in all that went on around him. Not a leaf rustled to the ground, as some passing breeze loosened its hold on the branch above, but he saw it eddying through the air; never a little ground squirrel frisked behind[15] some lichen-covered rock, or tree root, that Dick did not instantly note.

They presently found themselves traversing what seemed to be a rough belt of rocky land, where the trees were not very plentiful. It was even difficult at times to advance, and they had to be careful where they placed their feet, since a fall might result in serious bruises.

Just as they passed around a huge bowlder, that had at some time fallen from the face of the cliff towering above them, the two boys heard a queer, sniffing sound. Before either had time to draw back, there came shuffling into view, not more than fifty feet beyond them, a terrifying figure such as they had never up to that moment set eyes upon.

It was a huge bear, far larger than any they had met with in all their hunting trips along the Missouri. From some of the hunters connected with the exploring party they had heard the wildest stories concerning a monster species of brown, or grizzly bear that was said to have its home amidst the rocky dens of the mountains and foothills lying to the west. The Indians always spoke of this animal as though it were to be dreaded more than any creature of the wilds. The brave who could produce the long claws of a[16] grizzly bear was immediately honored with the head feathers of a chief.

Dick knew, therefore, that they were now facing one of these terrible animals. He could well understand the awe with which they were viewed by the red men, and the half-breed trappers, for the appearance of this monster was certainly alarming. Perhaps, if left to his own device, the more cautious Dick might have considered it best for them to decline a combat and, if the bear did not attack them, they could withdraw and seek a safer trail across the rocky ridge.

In figuring on this course, however, he failed to count on the impetuous nature of his companion. The hunter-instinct was well developed in Roger. He looked upon nearly everything that walked on four feet and carried a coat of fur as his legitimate prize, if only he could succeed in placing a bullet where it would do the most good.

So it came about that, as Dick started to put out his hand with the intention of drawing his comrade back, he was startled to hear the crash of a gun close to his ear. Roger had instinctively thrown his weapon to his shoulder, and, with quick aim, pulled the trigger.

Under ordinary conditions Roger was a very[17] clever marksman. There were times, however, when he failed to exercise the proper care, and then he was apt to make a poor shot. That may have happened in the present instance; or else, it must be true, as the Indians said, that the grizzly bear could carry off more lead, or survive more arrows, than any other living creature.

Dick was shocked to see that, instead of falling over as the shot rang out, the great bear started toward them, roaring, and acting as though rendered furious by the wound he had received.

There was nothing for it but that Dick should try to complete the tragedy. He aimed as best he could, considering the fact that the animal was now moving swiftly, if clumsily, in their direction, and pulled the trigger.

His rifle was always kept well primed and the powder did not simply flash in the pan; but he realized at once that he had not given the monster his death wound, for the bear still advanced, displaying all the symptoms of rage.

“We must get out of this, Roger!” cried Dick, for, as it would be utterly impossible for either of them to reload in time to meet the oncoming beast, they must either escape, or else engage in[18] a terrible fight with their knives at close quarters.

The remembrance of the long, sharp claws he had seen around the neck of the Sioux chief, Running Elk, caused Dick to decide on the former course. As he turned to run, he dragged Roger with him.

He remembered hearing that these terrible denizens of the Western mountains could not climb a tree like their black cousins. To this fact many a man owed his life, when attacked by a grizzly bear. As he ran, Dick strained his eyes to discover a convenient tree into which he and Roger might climb to safety.

Glancing back over his shoulder when a chance occurred, he saw, to his dismay, that the wounded animal was coming after them with a rush, and evidently had no idea of giving over the pursuit simply because his two-legged enemies were retreating.

“What can we do, Dick?” gasped Roger, now beginning to realize the foolishness of taking that haphazard shot at such a terrible beast, against which he had been warned by others who knew something of its ferocity.

“We must climb a tree, it is our only hope!” replied the other, between his set teeth.

“There’s one just ahead of us, Dick!” cried Roger, hopefully.

“We could never get up before the bear caught us, for there are no limbs low enough to be easily reached,” Dick answered. “A little further on I think I can see the one we must gain. Try to run faster; he is gaining on us, I’m afraid!”

Both lads were soon breathing heavily, for they found the uneven nature of the rock-strewn ground to be very much against them. But, fortunately, neither chanced to fall, and thus delay their flight and, while the oncoming grizzly was yet some little distance in their wake, they managed to reach the hospitable tree that offered them hope of a refuge.

“Up as fast as you can, Roger!” urged Dick.

Roger would not have stirred an inch, only he saw that his cousin was already clambering as fast as he could go. Impulsive, headstrong and even careless Roger might be at times, but he was no coward, and he would not climb to safety, leaving his chum to face any peril from which he was freed.

They managed to get fairly well lodged in the bare branches of the mountain oak before the[20] pursuing animal arrived. The bear stood up on his hind legs and tried to reach their dangling moccasin-covered feet, meanwhile snarling savagely, and manifesting the most determined desire to avenge his injuries.

“At any rate,” said Roger, “we both hit him, Dick, for you can see he is bleeding from two wounds. Oh! why did I let my gun fall when I stumbled that time? If I had it here with me now I could soon fix that fellow!”

“Then you must leave that to me this time, Roger,” remarked the other, who had managed to slip the strap of his gun over his shoulder as he drew near the tree, so as to have both hands free for climbing—and he had certainly needed them, too.

Dick now began to load his gun, meanwhile watching the actions of the furious bear. The grizzly was trying to gain lodgment among the lower limbs of the tree that had offered the fugitives an asylum; but he did not seem to know how to go about it, or to utilize those long, sharp claws that had been given to him by Nature more as a means of offense than for climbing purposes.

Several times he fell back heavily, only to give vent to his ferocity in sullen roars. Finally[21] Dick, having sent the patched bullet home with his ramrod, began to prime the pan of his long gun, so as to be ready to make use of the weapon.

“Make sure work of him, Dick!” Roger said, in trembling tones, as he saw the other draw back the flint-capped hammer of his gun, showing that it was ready for business.

The grizzly was still displaying all the signs of furious anger, and there seemed some danger that he might manage to gain lodgment among the lower limbs of the tree.

“No hurry, Roger! And, another thing, I’ve concluded that, since you brought this trouble on our heads by that unlucky shot, you should be the one to finish our enemy, not me!”

“Oh, Dick, do you really mean it?” cried Roger, filled with delight. “I’ve been saying over and over again that some day I hoped to be able to kill one of these monsters that the Indians fear so much. Do you intend to lend me your gun, and let me finish him?”

“If you’ll promise to keep cool, and watch for your chance to make the bullet tell. We haven’t[23] so many of them along with us that we can afford to waste even a single one.”

“I give that promise willingly,” said the other, as he stretched out his hand for the gun.

Having it in his possession, Roger’s first move was to lower himself a little. He meant to further excite the beast, and cause him to remain upright until the gun, being brought to bear on his head, within a foot or so of the small, gleaming eyes, could be fired with full effect.

“Careful not to go too far, Roger; he is waiting to make another try for you!” warned the watchful Dick.

So the young marksman paused, and, settling himself firmly in a crotch of the tree, bent forward. The gun was held at an acute angle, and the tiny sight near the terminus of the long, shining barrel could be seen against the dark fur of the bear.

When the beast opened his mouth to give utterance to another roar, Roger knew his time had come. His trembling finger suddenly pressed the trigger, there was a loud report, a still louder roar, and then a scuffling sound.

“He’s down!” yelled Roger, in anticipated triumph.

“Give me the gun, so that I may reload it!”[24] the other boy called, meanwhile observing the significant actions of the grizzly with mingled curiosity and satisfaction.

The animal had fallen over, and seemed to be struggling desperately to get up again on all fours. But that last leaden missile must have reached a vital part, for, as the seconds passed, these efforts became more and more feeble until, just as Dick primed his weapon again, there was a last spasmodic movement. Then the huge animal remained motionless.

Roger sprang down from his perch, in his usual reckless fashion; but there was no longer any danger, for the bear was dead. The boy placed his right foot on the huge bulk, and waved his hat in triumph; for, after all is said and done, he was but a lad, and this marked the highest point in his career as a hunter of big game.

“They’ll never believe it, Dick,” he exclaimed, “unless we carry back something to prove our story. And that means we’ve got to slice off these claws to show. After this we can have necklaces made of them, and the Indians will look on us as mighty hunters.”

“Just as you say, Roger, and, if you start with that one, I’ll attend to the other fore paw.[25] They are enough to give you a cold shiver. How our mothers would turn pale if they saw them, and knew what a narrow escape we had.”

“Yes, but our fathers would pat us on the back, Dick, and say that we were ‘chips of the old block,’ because they many times took their lives in their hands the same way, when founding their homes on the frontier, and know what it is to face the perils of the hunting trail.”

Dick kept on the alert while engaged in his task of severing the claws of the dead bear. After having seen those strange Indians passing, not so very long ago, he realized that there was always more or less danger of others being in the neighborhood. And those three loud reports, as the guns were fired, would carry a long distance, telling the natives that white men were around.

Nothing occurred, however, to give them further alarm, and presently, the claws having been obtained, the two boys continued on their way toward the distant camp.

It was at least two hours later that they sighted the Mandan village, near which the camp of the exploring expedition had been pitched.

Knowing that, any day now, winter, while somewhat delayed, might break upon them, Captains[26] Lewis and Clark were preparing for a long stay here, and their hunters were laying in a supply of fresh venison to be made into pemmican. (Note 2.)

When the two boys reached the camp, bearing the terrible claws of a grizzly, their arrival caused a great sensation. Roger did not spare himself in relating the story, for he knew his own failings; but, since it had come out well, he received nothing but congratulations.

The old forest ranger, Jasper Williams, lingered after the others had gone, and Dick saw that he had some sort of communication to make. The boys had managed to save Jasper’s life when they were all prisoners of the warlike Sioux, and, ever since, the trapper had felt a great interest in the cousins.[4]

“I’m going off with two companions on a short trip,” he now told the boys. “We may be gone a week, or even two, for we wish to investigate the truth concerning some stories that have come to us concerning a wonderful valley among the mountains, where all sorts of strange animals abound, even to goats that leap off the loftiest crags, and striking on their curved horns, rebound safely. It is even possible that,[27] if we find the stories true, we may spend most of the winter there trapping and hunting.”

The boys were sorry to learn this, for they were fond of Jasper and had hoped to see much of him during the long winter.

“We start in an hour, so as to get to a certain point by sundown,” the ranger told them further. “You see, the winter has been holding back so long now that it is apt to start in any time with a furious storm, and the sooner we get to where we are going the better. The snow falls very deep in the mountains, and there are avalanches that bury everything under them forty feet deep.”

It was in the heart of Roger to hint that they would be delighted to accompany the ranger; but a look from Dick caused him to bite his tongue and refrain. Afterwards, when they had seen the three men start forth, and cheered them on their way, Dick consented to explain his reasons for motioning to his cousin to say nothing about going along.

“We can’t expect to be in everything, you see, Roger,” he said. “After all, we are only boys, and some of the men here still look on us as inferior to them in ability to accomplish things, because they are so much stouter and stronger.[28] We can find plenty to occupy our minds and hands while they are gone. Perhaps, who knows? should they come back, one of the men may not want to return with Jasper, and that would be our chance to try for an invitation.”

“I suppose you’re right, Dick,” grumbled Roger. “You nearly always hit the nail on the head. But it would have been a fine trip for us. And, now that I’ve met with and killed one of these terrible grizzly bears we’ve heard such tales about, I’m burning with eagerness to shoot one of the strange mountain goats Jasper was telling about, that have such immense, curved horns.”

“Plenty of time for all that, Roger,” the other told him. “The whole winter is before us, and when spring comes, as we head further into the West we will have to cross many mountain chains before we see the ocean. Among them we will surely come across numbers of these queer goats, as well as elk, buffalo and antelope.”

So Roger finally became reconciled to what could not be changed. There was really no occasion for his feeling that way long, because Dick busied himself in mapping out new ventures every night, as they sat before the campfire,[29] with hands twined about their knees, and talked of home, and what wonderful sights they had looked upon since leaving the settlement of St. Louis.

Two days thus passed, and the boys were looking forward to doing further roaming, if the weather permitted, on the following morning. The afternoon was drawing to a close, and in the west the sun sank toward his bed among the far distant mountain peaks, while the heavens began to take on a glorious hue.

The camp of the explorers was a bustling scene at such an hour, for preparations were under way for the evening meal, the fires burned cheerily, and it was almost time for the guard to be changed.

Being under strict military rule, the members of the expedition day and night pursued their vocations with the same care as though they really anticipated an attack from some unseen enemy. Guards were posted at night, and no one was allowed to enter or leave the camp without giving the countersign.

This was done partly because Captain Lewis and Captain Clark believed in discipline, one of them having been brought up in the little army of the new republic. There was also another[30] reason for keeping a constant watch. There had been a number of French half-breeds in this region before their arrival, and these men, who had been reaping a rich reward trading with the various tribes of Indians, viewed the coming of the Americans with great disfavor, believing it might bring their harvest to an untimely end.

Rumors had reached the ears of the commanders of the little force that some of these men were trying to excite the Sioux to take up the buried hatchet, and proceed in force against the Mandans and their new white allies.

On this account, then, it was necessary that the camp be guarded against a sudden surprise. At least, if trouble came the explorers did not mean to be caught napping by the cunning redmen.

“You don’t think it feels much like snow, do you, Dick?” Roger asked, as they stood looking around them, with the sun commencing to drop down behind the horizon.

“The signs do not show it,” the other told him; “but you know they sometimes tell us wrong. The season is so late, now, that we’re liable to get a heavy storm any day and, as it’s growing colder all the time, it will come as snow and not rain. Once it falls, the Indians say we[31] will not see the bare ground soon again. But what are the men running to the other side of the camp for, do you suppose?”

“Listen, one of them just shouted that a man was coming, mounted on a horse,” said Roger.

“That sounds as though it might be a white man,” added Dick, as they hastened through the camp toward the other side where they might see for themselves what all the commotion meant. “Horses are not common in this country. We are running short ourselves, since we’ve had some stolen by prowling Indians, two died, and the three men who started down the river took as many more with them.”

By this time they had arrived at a point where they could look toward the southeast, for it was to that quarter the attention of the members of the expedition seemed to be directed.

Dick uttered an exclamation that was echoed by his cousin. Their faces expressed the utmost dismay and alarm and there was good reason for this, as the cry that broke from Roger’s lips indicated.

“Oh! Dick, what can it mean? There is the messenger who carried away our precious paper, coming back to camp on a worn-out horse. Something terrible must have happened!”

“I’m afraid you are right, Roger,” Dick replied, as the two pioneer boys hastened to be among the first to meet the rider when he came jogging into camp.

That something had, indeed, happened was easy to see from the dejected manner of the messenger. His face bore a deeply chagrined look, as though there was some reason for his feeling ashamed.

He had evidently pushed his horse hard all day, for the animal was worn out, and reeking with sweat, despite the fact that there was a decided chill in the air.

The man dropped wearily from his hard saddle. He came very near falling, for, after sitting in that constrained attitude for many hours, his lower limbs were benumbed, so that for a brief time he did not have the full use of them.

By this time Captain Lewis had heard the[33] clamor, and come out of his tent to ascertain what had happened.

Possibly he may have supposed that it was only a visit from some of the Mandans on an errand connected with their now friendly association with the whites. Then again, the commander may have wondered whether one of the hunting parties had arrived with some unusual species of game, such as none of the explorers had ever seen before.

When, after striding forward to join the crowd, he saw the dusty messenger, a frown came upon his ordinarily pleasant face. Captain Lewis knew that something must have gone amiss, or the man who, with two companions, had started over the back trail several days before would not have returned to camp in this way.

“What does this mean, Mayhew?” he demanded, as he came up, the others parting to allow a free passage, though naturally the two boys stuck to their posts, because they had an especial interest in whatever story the returned messenger might be about to relate.

“Something has happened, Captain Lewis, I’m sorry to tell you, and not at all to my credit,” replied the man, trying to calm himself,[34] though it was evident that he was laboring under great stress of emotion.

“Were you attacked on the way?” asked the President’s private secretary, who had been entrusted with most of the responsibility of the excursion, and therefore felt more keenly than any one else the possibility of failure.

He had taken great pains to keep a daily account of the trip up to that point, and this diary he had sent to the head of the Government in the care of the three men, one of whom now stood before him with dejected mien.

“We believed we had taken all ordinary precautions, Captain,” the messenger continued, making a brave effort to confess his fault as became a man; “but, in the darkness of the night, they crept upon us without any one being the wiser. My horse gave the alarm with a whinny, and, as I awoke, it was to find that the camp had been invaded by several enemies.”

“Could you not see whether they were Indians or otherwise?” asked the commander, as though a sudden suspicion had flashed through his brain.

“It was very dark, and our eyes were not of much use, sir,” the messenger told him in reply. “We purposely refrained from building[35] anything but a small cooking fire, and that was in a hole so its light might not betray us to any wandering Indians. But they were not red men who attacked us; of that I am assured.”

“Why are you so certain of that?” inquired Captain Lewis.

“We were all struggling with the intruders, who had evidently thrown themselves upon us just as my horse gave the warning whinny,” the messenger explained. “I am positive that my hands did not clutch the greased body of a redskin, when I tried to throw him. Clothes he certainly wore, such as all frontiersmen do. I could feel the deerskin tunic, with its fringed edges. Besides, I tore a handful of his beard out in my struggles.”

“No more proof is needed!” declared Captain Lewis. “They must have been some of the French half-breeds. But go on, Mayhew, have you other distressing news for us? What of your two companions; I hope they did not meet their fate there in the darkness?”

At that the man’s face lighted up a trifle. He had told the worst, and the rest would come easier now.

“Oh, no, indeed, sir, none of us were badly injured, strange as it might appear,” he hurriedly[36] explained. “Bruised we certainly were, and greatly puzzled at both the attack and its sudden ending, that left us still alive; but we were at least thankful it had been no worse!”

“And then what did you do?” continued the leader of the expedition.

“We stood guard with our guns ready the remainder of the night, sir, but we were not again disturbed. It was toward morning that I made a sudden discovery, which is what has brought me back to the camp to report, while my two companions kept on with your documents intended for the President.”

Captain Lewis drew a deep sigh of relief. That was the first intimation he had received that his precious communications had been saved.

“Then explain why you have returned, if the papers were saved!” he demanded, as though puzzled.

“You forget, sir, that I was entrusted with another paper, which you ordered me to personally hand to the grandfather of the two boys who joined us.”

When Mayhew said this, Dick and Roger knew that a new trouble had descended upon their heads. He must have lost the paper in[37] some manner and yet neither of the lads was able to understand how it could have happened.

“Do you mean to say the paper they set such store on is missing?” Captain Lewis demanded.

“I had it securely hidden in a pocket inside my tunic, Captain,” replied the humbled messenger; “but, when I came to look for it, it could not be found. When morning came we spent a full hour scouring the vicinity, but it was useless. And there had not been a breath of wind to carry a paper away. It must have been taken from me while I was struggling with that unknown man.”

“This is indeed a strange story you bring back with you, Mayhew,” continued the leader of the expedition, looking keenly at the other, who met his inquiring glance as bravely as he could. “Stop and consider, did you hear anything said that might give the slightest clue concerning the identity of the thieves?”

“But one word, sir, and that was a name,” came the ready answer. “The man with whom I was grappling, as we rolled over and over on the ground, suddenly let out a loud cry. I plainly heard him say the one word ‘Alexis!’ And then he suddenly threw me aside, for he was very powerful.”

“And did the fighting cease immediately?” asked Captain Lewis, quickly.

“Yes, sir, the others seemed to take that word as a signal, for the next thing I knew my companions were calling out to ascertain whether I had been seriously hurt. I found that they also had been bruised, and one had a knife wound in the arm, but not of a serious nature.”

The captain turned toward Dick and Roger.

“You have heard what Mayhew says, my boys,” he remarked. “Does it afford you any sort of clue as to the meaning of this mysterious attack in the dark, and the seizure of the paper you were sending home?”

“I am afraid it does, Captain,” Dick replied.

“You recognize the name, then, do you?”

“It is that of the grown son of François Lascelles,” replied Dick; “the rascally French trader who has bought up the claim against our parents’ holdings down near the settlement of St. Louis.”

“Then it is possible that they followed you all the way up here, and, having obtained the assistance of some equally desperate border characters, laid a cunning plot whereby they meant to win by foul means, where fair could not succeed![39] What puzzles me most of all is how they could know that Mayhew carried the paper. I should dislike very much to believe we had a traitor in our little camp!”

The captain looked around at the assembled men with a serious expression on his face, which caused some uneasiness among the soldiers, frontiersmen and voyageurs who made up the expedition. They had always shown themselves loyal to their commanders and, when the finger of suspicion pointed their way, all felt the disgrace keenly.

Mayhew it was who came to their relief.

“I could never believe, sir, that any one here could be so treacherous,” he hastened to say, as though anxious to take the entire burden of responsibility on his own broad shoulders, in which he proved himself to be at least a man. “I have been seriously thinking it over as I rode all day long, and believe I can see how it may have been known that I carried the boys’ packet.”

“Then explain it, Mayhew; for I must confess that the whole thing is a great puzzle to me,” Captain Lewis told him.

“When they saw us depart they knew, of course, that you would be sending a report of[40] the progress of the expedition to the Government at Washington, sir. They must have also surmised that the boys would have influenced Jasper Williams to sign the paper that would free their homes, and that one of us must be carrying it to St. Louis. Do you not think that is reasonable, Captain?”

“Yes, but tell me how they could have picked you out as the one bearing it?” asked the other, impatiently.

“The only explanation I can give is that they must have been in hiding near us at the time we camped,” continued Mayhew. “I remember taking the packet out, so as to fasten it in my pocket anew, since it was not as secure as I desired. I believe some one was watching from the bushes near by, and saw me do it. Then, while we struggled there on the ground, he managed to tear open my tunic, and, while half-choking me, snatched the paper away.”

“And giving a prearranged signal at the same time to tell of his success,” remarked the captain, this time nodding his head in the affirmative, as though he had come around to the same way of thinking as Mayhew.

“The fighting ceased as if by magic,” declared the messenger. “One minute all of us[41] were struggling as for our lives; then that cry rang out, and immediately we found ourselves deserted. We heard retreating footsteps, a harsh laugh, and shortly afterwards the distant hoofstrokes of horses being ridden rapidly away.”

“And you slept no more, but stood on guard, not knowing but that the unseen and mysterious foes might return to finish their work?” suggested Captain Lewis.

“It was well on toward morning at the time, sir, for we had slept. I think they took a lesson from the redskins, who always make it a point to attack a camp just before the coming of dawn. They believe that men sleep heavier then than earlier in the night.”

“You talked it over with the other men after the paper was missed, did you,” continued the commander, “and decided that, while they continued on their long journey, it was your duty to return and report your loss?”

“I was broken-hearted over it, sir; but it was my duty. If I have been neglectful, I must stand the consequences. But we saw nothing suspicious, and did not dream of danger until it burst so suddenly upon us.”

“I shall say nothing about that until I have[42] consulted with Captain Clark, who, you know, is the military leader of the expedition. Have your horse rubbed down, and secure food and refreshment for yourself, Mayhew. I must talk with these boys now.”

Turning to Dick and Roger, Captain Lewis told them to follow him to the shack where he and Captain Clark transacted whatever business they found necessary for the conduct of the expedition. It had been built so that the severe cold of winter might not interfere with their comfort and such was the success of the experiment that other cabins were even then in process of construction for the remaining members of the party.

Here they found the military head, busy with his charts. The leaders knew so little of the mysterious country which they were bent on exploring in the coming spring that notes were carefully kept of every scrap of information obtainable.

Often this consisted of fragmentary tales related by some wandering Indian concerning the strange things he had encountered far away toward the land of the setting sun. Allowances were made for the superstition of the natives[44] when a record was kept of these tales; but often there seemed a shred of truth behind it all which could be made to serve the purposes of the daring explorers.

So deeply interested was Captain Clark in some work on which he was engaged, and which seemed to be in the nature of making a new map of the country through which they had already passed, that he had actually paid no attention to all the shouting outside.

When his colleague came in, accompanied by the two boys, Captain Clark realized for the first time that something out of the ordinary must have happened.

He listened intently as the story of Mayhew’s strange loss was unfolded, asked a number of questions that put him in possession of all the known facts, and then gave his conclusion.

“I am of the same opinion as the rest of you!” he declared. “It must have been the work of the men who would profit should that paper fail to reach the Armstrongs by spring; this French trader, François Lascelles, and his equally unscrupulous son, Alexis.”

“But to think of them following us all the way to this point! It seems almost impossible,” urged the other captain.

“Why should it be considered so?” asked the soldier, who appeared to grasp the salient points much easier than the President’s private secretary had done. “We have encountered no difficulties that a party of hardy voyageurs and trappers might not have overcome. Besides, it is quite possible that this same trader may have been in this country before now. The French were in possession of the great Mississippi Valley all the way down to the Gulf many years before it came into the hands of the United States Government. They must have had trading posts far to the west, and their half-breed trappers have taken beaver and all other fur-bearing animals from the streams of the Far Northwest.”

“You are right, Captain Clark,” said the other, warmly “and, after hearing your reasonable explanation, I can well believe that these men are no strangers to the region of the headwaters of the Missouri.”

“I also agree with Mayhew regarding the camp having been watched,” continued the soldier, gravely. “They suspected we would be sending back a report of our progress, and surmised also that these brave boys would either themselves carry their paper to their homes or[46] else give it into the keeping of our messengers. Just how they knew that Mayhew was carrying their document, and not either of the other messengers, I cannot say, but it seems that they managed to do so.”

He turned to Dick and his cousin to say:

“I am sorry indeed that this new trouble has befallen you, my lads, but throughout your long journey you have shown such fortitude, and such determination to succeed, that I feel sure you will not be downhearted now.”

“Thank you, sir,” replied Dick, for Roger could not say a word, since a lump in his throat seemed to be choking him. “We have been brought up by fathers who never knew what it was to despair. I was just wondering whether François Lascelles would immediately destroy that document, and then go on his way, resting under the belief that he had ruined all our work of months. He may have forgotten one thing, which is that Jasper Williams still lives, and can duplicate his signature, with both of you for witnesses.”

“Just what I was about to say,” declared the soldier, with a smile of satisfaction, “and it pleases me to know that you have hit upon the same idea. Yes, while this Lascelles may think[47] he has won his fight, the battle is never over until the last trump has sounded. When you again secure the signature you require, we will see to it that another messenger is dispatched to your home bearing it.”

Roger managed to find his voice then.

“But how are we going to reach Jasper Williams,” he asked, anxiously, “when he has gone off to find that wonderful valley where the game is so plentiful, but which the Indians are afraid to visit on account of the spirits that guard it?”

The two captains exchanged glances. They realized that difficulties indeed lay in the way of accomplishing the plan they had so cheerfully laid out.

“He may come back in a week or two, he told me,” Dick explained, “and then again it is possible, if his companions agree, and the place suits them, that they may not return until late in the winter.”

“And it would be too late then to get the paper to our people at home,” sighed Roger, looking exceedingly downcast.

“I think I voice your sentiments as well as my own, Captain Clark,” said the private secretary to the President, “when I make this suggestion. We can place one of our trusty hunters in charge[48] of these lads, and send them off to try to find Jasper Williams and his party, whose general direction we already know.”

“I am of the same opinion, Captain,” added the soldier, promptly, showing that he must have been thinking along similar lines. “Indeed, if an immediate start were made, they might even overtake the others on the way, for I do not fancy they will be in any great hurry, since they have orders to make notes of all they see by the way.”

At hearing this Roger brightened up considerably. As usual, a way out began to appear when things had become almost as gloomy as seemed possible. As for Dick, he eagerly seized upon the chance to be doing something. Like most pioneer boys, these Armstrong lads had been brought up to strive to the utmost when there was anything worth while to be attained.

“Oh, thank you, Captain Clark, and you, too, Captain Lewis!” he hastened to say, “that is the kindest thing you could do for us. We will get ready to start in the morning and, if our old luck only holds out, we shall expect to come up with Jasper Williams inside of a few days.”

“You will need a good trailer to assist you,” remarked the soldier, “and among all our men I[49] do not know of any who is the equal of Mayhew if only you would not have any ill feeling toward him on account of what his carelessness has already cost you.”

“Why, it was hardly his fault, that I can see, sir,” declared Dick, “and I have always liked Benjamin Mayhew very much. If he cares to go with us, tell him we will be only too glad of his company.”

“Yes,” added Captain Lewis, who knew his men as few commanders might, “and this I am sure of—Mayhew will strive with might and main to retrieve himself. You will find that he has really taken his bad luck to heart. He will want to prove to us that he is capable. He will do wonders for you, lads, and I believe you show the part of wisdom in wishing him to accompany you.”

“Then consider that settled,” said the soldier. “I will have Mayhew in here presently, and talk with him. You can make your preparations for an early start in the morning.”

“And both of us trust success will crown your gallant efforts to serve your loved ones at home,” said Captain Lewis. “I well remember your fine old grandfather, David Armstrong. His name is familiar to all who know the history[50] of the early settlements along the Ohio, where such valiant pioneers as Daniel Boone, Simon Kenton and Colonel Harrod led the way into the wilderness, and lighted the torch of civilization.”

It was very pleasant for the boys to know they had such strong friends in the leaders of the expedition making a track across the newly acquired possession of the young republic.

When they left the shack they somehow seemed to feel anything but downhearted. Indeed, with the buoyancy of youth they now faced the future hopefully, almost certain that they would quickly find Jasper Williams again, and bring him back to the camp, where he would make out and sign a new document, to be witnessed by both the captains, whose names were sure to carry weight in any court of law.

“It might be a great deal worse,” admitted Roger, as he accompanied his cousin to their quarters in order to make what simple preparations they thought necessary for the early morning start.

“Many times so,” Dick assured him. “Why, after all, this may turn out to be one of those blessings in disguise our mothers have so often told us about.”

“You will have to explain that to me, Dick,” admitted the other boy, “for I own up that it is too much for my poor brain to understand.”

“Listen, then,” continued the other. “What if that scheming François Lascelles had delayed his attack on the messengers for days and even weeks, until they were almost at St. Louis, and then secured our paper? We would never have known about its loss, and could not send another!”

“That is so,” assented Roger, nodding his head as he managed to grasp the point his companion was making.

“Then again,” continued Dick, who could follow up an argument with the skill of a born lawyer, “suppose the three messengers had been killed in that night attack, we should not have known a thing about it. Our paper, as well as the valuable reports sent to the President, would have been lost.”

“Yes, and, Dick, we would have gone on enjoying ourselves all through the winter, never knowing that we had failed to save our homes.”

“As it is,” continued the other, “Lascelles, believing he has cut our claws, may take himself out of this section of country, so that another[52] messenger would have nothing to fear from him or his band.”

“You are making me ready to believe that, after all, this may have been the best thing that could have happened,” laughed Roger, as he began to examine his bullet-pouch to ascertain just how many leaden missiles it contained, and then pay the same attention to his powder-horn. For it was of the utmost consequence that in starting forth on this quest, that might consume not only days but weeks, they should be amply prepared for any difficulties that might arise to confront them.

That was destined to be a busy evening for the two lads. They molded bullets, replenished their stock of powder from the stores of the expedition, talked over matters with Mayhew, who seemed greatly pleased at the confidence they expressed in him, and even managed to lay out something of a chart for their guidance.

This map was made up of suggestions from Captain Clark, who had talked with Jasper Williams before the latter and his two companions left camp, and knew in a general way what direction they expected to take.

Before Dick and Roger allowed themselves to[53] think of sleep, they had everything arranged for the start in the morning. It was a great undertaking for two boys to think of venturing upon, but certainly not any more so than when they left their homes near St. Louis, and headed into the trackless West with the intention of overtaking the Lewis and Clark exploring expedition.

And both of them had faith to believe the same kind power that had watched over their destinies thus far would still continue to lead them by the hand.

With the first peep of dawn both lads were astir. Their hearts and thoughts were so wrapped up in the desire to once more find Jasper Williams and obtain his signature to a duplicate document, that, to tell the truth, neither had slept at all soundly.

As all preparations had been completed, there was little for them to do except get their breakfast, shoulder their packs, say good-by to the two leaders of the expedition, as well as the men, and start boldly forth.

Before the sun was half an hour above the horizon the little party of three had left the camp and the nearby Mandan village behind them, and were on their way.

It was known just where Williams and his companions expected to spend their first night, having started at noon, so none of them felt any necessity for trying to follow the trail until that point had been reached.

All through the morning they moved on, and[55] as noon approached drew near the place where the camp had been mapped out.

“That much is settled, Dick, you see!” ventured Roger, as he pointed to where the dead ashes of a fire were visible, there having been no high wind to blow them broadcast.

“Yes, they spent the first night here,” admitted the other, “and so they must have just two and a half days the jump of us.”

“That’s a long start,” grumbled Roger.

“Well, we expect to keep on the move each day longer than they will,” explained the other. “Then again, they may find some place so much to their liking they would conclude to spend a couple of days there hunting or trapping. Jasper is always one to say a ‘bird in the hand is worth two in the bush’; and those stories about the wonderful valley that is haunted by the spirits may turn out to be fairy tales after all.”

“And now the real work begins, when we have to follow this trail,” added Roger, who acted as though he did not want to lose a single minute.

“That is not going to be such a hard problem, I should think,” Dick told him. “In the first place, they will not try to hide their trail[56] very much, because they do not expect hostile Indians to follow them; though at night, of course, they will take every precaution against a surprise. And then again, Roger, we know something about trailing, while Mayhew, here, has not his equal in our camp, so Captain Clark told me.”

Mayhew did not hear this, for he was busy looking around the camp, examining the cold ashes, and in various ways picking up little details that an ordinary person would never have been able to discover.

“Unless—well, I might as well own up, Dick,” said Roger. “I’ve been wondering whether after all that tricky Lascelles would be satisfied to go away from here after destroying our paper. He might know about Jasper Williams’s trip to the Wonderland the Indians tell about, and try to capture him, so as to keep him from signing another paper for us.”

Dick shook his head as though he did not believe such a thing could be possible.

“It might happen that way, Roger, but I feel pretty sure we’re well rid of that rascal. Let us keep the one thing before us to find Jasper, and fetch him back to camp again in time to start afresh.”

“There, Benjamin is beckoning to us, Dick; he is ready to start off,” and Roger eagerly obeyed the finger of the guide, for he was anxious to be on the move.

They did not even stop to make a fire and cook anything at noon, but munched some food that had been brought along with them. Roger begrudged even a ten-minute stop, when it was not absolutely necessary.

“We ought to keep on the move as long as daylight lasts,” he declared. “After it gets dark there’ll be plenty of time to rest, and do a little cooking. By then we might possibly be lucky enough to reach their second camping place.”

Time passed on, and constantly the little party pressed ahead. Just as had been hoped, Williams and his companions did not seem to care to hide their trail; though, when the chance offered, they always took a course that gave them an opportunity to walk on hard ground, or even rocks, which actions sprang from the natural caution of frontiersmen.

Slowly the sun sank toward the golden West. The boys surveyed a low-lying bank of somber gray clouds and wondered if the long delayed opening snow-storm of winter might spring[58] from that source. Roger as usual found cause for new anxiety in that possibility.

“If it does come down on us, you see, Dick,” he said, complainingly, “the first thing we’d lose the trail we’re following, and then we’d be in a nice pickle. What could we do if that happened?”

“Just as we did when following the explorers along the Missouri,” he was told. “Use our heads to figure things out and take chances. It has worked with us lots of times, and will again.”

“You mean we’ve got a general idea where that valley they are heading for lies, and might get there even without following their trail; is that it?”

“Yes, and to reach it we will have to pass through the country the Indians fear so much, so that, before we are through with this trip, we may know whether there is any truth in those strange tales or not.”

“They tell of a large and beautiful lake in which the river with the yellow stones along its bank has its source,” Roger went on, recalling all he had heard. “Then there are marvelous fountains that have spirit breath, the red men say, and spring up from holes in the[59] ground, to try to reach the skies. They tell of many colored stones, and mud as blue as the heavens; they say it is the home of the Evil Spirit, and that no one’s life is safe who wanders that way, and passes a single night there.”

“But you do not believe such silly stories, I hope?”

“Whether they are true or not, I am not prepared to say,” replied the other, after a little pause; “but you ought to know me too well to think so ill of me as to believe that a hundred evil spirits would keep me from exploring that country of the big lake and the flowing fountains, and all the other strange things!”

So they talked as they moved along. Much of the labor of following the trail fell upon the shoulders of the frontiersman, Mayhew, who seemed only too glad to assume the responsibility. Not once did he lose the track. When it crossed a stony section he seemed to be able to decide just the point for which the others must have been making, and in all cases he quickly pointed out the tracks again where the soil became soft enough to allow of impressions.

They had seen considerable game while on[60] the way, though not stopping to obtain any fresh meat. All that could keep until they had overtaken those who were ahead. So, although Roger was greatly tempted when he discovered a trio of big elk feeding in a glade not a quarter of a mile to windward, he shut his teeth hard and told himself that on another day his chance would come.

Here were jack-rabbits in plenty, gophers whistled in the little open stretches, antelopes were seen feeding on the prairies that lay between the uplifts, while ducks and wild geese swam on the waters of small ponds, and might easily have been bagged had the boys cared to take the time.

Some of the rapid little streams they crossed looked as though they might be well stocked with splendid trout; indeed, they often saw fine gamy fellows dart out of sight beneath some overhanging bank. They loved to fish as well as any boys who ever lived; but just then felt it necessary to put the temptation behind them.

Once they even discovered a herd of buffalo not a great distance away.

“How I would like to creep up on them, and pick out a nice young bull to drop,” said Roger. Then he shook his head and heaved a sigh, for[61] there came before his mental vision the happy home so far away, over which such a dark shadow rested, and which could only be dissipated through the efforts of himself and his cousin.

“One thing we ought to remember with thankfulness,” remarked Dick, “and that is that so far we have seen not a single sign of Indians. The Mandans do not come this way very often, you know, and the Sioux are even more timid about venturing into the region of the Bad Lands; but there are other tribes who are not so fearful.”

“You mean the Blackfeet and the Crows,” Roger added; “both of them fierce fighters, and hating the whites like poison. I’m afraid we will see more or less of them before we get back to camp.”

“We have always been able to take care of ourselves in the past, remember, Roger, and can again. Here are three of us, well armed and determined. If the Indians try to do us injury they will find two can play at that game. Our fathers had to fight just the same kind of enemies away back there on the Ohio, and if we’re ‘chips of the old block,’ as they tell us, why shouldn’t we do as well? There, Benjamin[62] has discovered something, and wants to show us.”

Mayhew showed the boys where Jasper and his two companions had dropped down behind some bushes, and crawled along for quite a distance.

“Here is where they stopped to raise their heads,” explained the guide. “I think they must have discovered some enemies over in that direction, for they always kept peering out that way. See, here is where they even plucked some of the dead leaves from this bush to glue their eyes to the opening. It is an old hunter’s trick for a moving branch might betray the one in hiding.”

A short time afterwards Mayhew seemed pleased, for he announced another radical change in the trail he was following so carefully.

“The danger was passed successfully, you can see,” he told the boys, “for here they arose to their feet again, and hurried on, perhaps bending low, because they were careful to keep behind these rocks. After this we may not find it so easy to follow the trail, for they have scented danger.”

It turned out just as he said, and from that[63] time on it required the exercise of considerable woodcraft on the part of the frontiersman to enable him to detect the tracks of the three whom they were pursuing.

Now Jasper and his two friends had followed an outcropping stone ledge as far as they could, and swung across a patch of soft ground by means of a dangling wild grave-vine. Another time they had stepped upon an overturned tree, proceeded some distance along the trunk, and then made a great leap for some spot where soft-soled moccasins would leave but scant evidence of their passing.

But Mayhew was acquainted with all these methods of concealing a trail. He had spent much of his life in the wilderness, and knew Indian ways as well as any man Dick and Roger had ever met.

Gradually that long afternoon gave place to the coming of night. Shadows began to steal out from among the trees and stalk boldly. More and more difficult did it become for the trailer to see the faint tracks of those he was pursuing. Finally he came to a full stop.

“It is no use trying further, lads,” Mayhew told them, “for there would be constant danger of losing the trail entirely. Unless we choose[64] to risk lighting torches, and keeping on, we must make camp here, cook something to eat, and then get what rest we may, looking to a new day and an early start.”

Although Roger hated to give up, he knew there was nothing else to be done.

There was little that the two lads did not know about making a camp, for they had been accustomed to spending nights in the woods ever since they first learned to handle a gun, and bring down the game so necessary for daily food.

The spot chosen by their guide for passing the night was as suitable as could be found at that late hour. Around them lay the woods, the trees tall and not of any generous girth, for the slopes of the hills bordering the Yellowstone are covered with a growth of pine that is not noted for its size.

When Mayhew tossed his pack aside the boys followed suit. They had made a long day of it, and were tired, though ready enough to keep moving could it be to their advantage.

The woodranger started to make his little cooking fire, while Dick and Roger arranged their blankets and made other preparations for the night. If they noticed the actions of the[66] guide at all it was with slight interest, for both were fully acquainted with the methods which he used in his work.

Like many other things copied from the Indians, this idea of a small blaze that could not betray their presence had become a part of every woodsman’s education. The way in which it was done was very simple.

First a hole was scooped out of a place where there was something of a depression, and in this a small quantity of inflammable tinder was placed. Flint and steel, upon being brought violently together, produced the necessary spark, and the handful of fine wood took fire.

It was carefully guarded on all sides so that not a ray might escape to attract attention; and, when sufficient red coals had accumulated, what cooking was necessary could be carried on over them.

When properly done, this sort of fire might remain undetected twenty paces away by the possessor of the keenest vision. Only the presence of suspicious odors, such as of burning wood, or food cooking, might betray the fact that there was a fire in the vicinity.

All Mayhew wanted was to heat some water, and make a pot of tea, of which he was very[67] fond, although it was a great luxury of that early day. The supper itself would have to be eaten just as it was. They had a fair amount of bread, such as was baked by the camp cook; plenty of pemmican, and that was about all. If the food supply ran short they must depend wholly on what game they could bring down with their rifles.

Most boys of to-day would view such a limited bill of fare with alarm, and think starvation was staring them in the face. These lads of the frontier, however, were accustomed to privations. They faced empty larders every time stormy weather prevented hunting. And early in life they learned that it does no good to borrow trouble.

The night closed in around them. Dick and his cousin lay in their blankets and conversed in whispers, while Mayhew continued to busy himself over his tiny fire.

Around them lay the wilderness that was almost unknown to the foot of white man, yet it did not seem to awe these adventurous souls, simply because they had been brought up in the school of experience, and were familiar with nearly all the ordinary features of a vast solitude.

When the guide had his pannikin of tea ready he told the boys to fall to, and, being sharp pressed by hunger, they did not wait for a second invitation. Meager though that supper may have been, there was not a word of complaint, even from Roger. The pemmican tasted good to him, the dry bread was just what he craved, and the bitter decoction which Mayhew had brewed seemed almost like nectar.

Having accomplished its mission, the tiny fire was allowed to die out. Mayhew managed to light his pipe, which appeared to afford him much solace, and all three lay there, taking things as comfortably as possible, while they discussed in low tones the prospects ahead of them.

Each one offered an opinion with regard to what sort of weather they might expect in the near future. In doing this they consulted the stars, together with the prevailing winds, and whether this last seemed to carry any moisture in its breath since that would indicate approaching rain or snow.

It was the general belief that the prospect could be set down as uncertain. It might storm, or another fair day might speed them[69] on their way; matters had not as yet developed far enough to settle this question.

The silence that had accompanied the coming of the night no longer held sway.

From time to time various sounds drifted to their ears to announce that the pine forest bordering the banks of the mysterious Yellowstone River were the haunts of many wild animals that left their dens, after the setting of the sun, for the purpose of roaming the wilderness in search of prey.

Far in the distance they could occasionally hear, when the wind favored, the mad yelping of a pack of gray mountain wolves, undoubtedly on the track of a stag which they meant to have for their midnight supper, if pertinacity and savage pursuit could accomplish it.

Closer at hand there came other sounds. Once the boys stopped speaking, and bent their heads to catch a repetition of a peculiar cry that would have sent a cold chill through any one unaccustomed to woods life.

“That sounded like a painter to me, Dick!” ventured Roger, handling his gun, so as to make sure the weapon was within reach of his hand.

Of course a “painter” meant a panther, for it[70] was so called by nearly all back-woodsmen and pioneers of that day. And these two lads knew well what a fierce antagonist one of those great gray cats became when wounded, or ferociously hungry.

“Yes, that was just what I thought,” replied Dick; “but there isn’t much chance he’ll bother to pay us a visit to-night. The woods are big enough to give him all the hunting he wants, without trying to invade our camp.”

“There seems to be plenty of life in this valley of the Yellowstone River,” the second boy continued, “and, even if Jasper Williams fails to find the Happy Hunting Grounds he is looking for, he might do lots worse than stay around here.”

“Yes, I am sure there must be lots of fur to be picked up, and we saw plenty of elk, you remember, Roger, as well as other food animals. From what we have learned, the Indians never come in this direction unless they are compelled to by a scarcity of game in other places.”