BY HARRISON ADAMS

ILLUSTRATED

| THE PIONEER BOYS OF THE OHIO, | |

| Or: Clearing the Wildernes | $1.25 |

| THE PIONEER BOYS ON THE GREAT LAKES, | |

| Or: On the Trail of the Iroquois | 1.25 |

| THE PIONEER BOYS OF THE MISSISSIPPI, | |

| Or: The Homestead in the Wilderness | 1.25 |

| THE PIONEER BOYS OF THE MISSOURI, | |

| Or: In the Country of the Sioux | 1.25 |

| THE PIONEER BOYS OF THE YELLOWSTONE, | |

| Or: Lost in the Land of Wonders | 1.25 |

| THE PIONEER BOYS OF THE COLUMBIA, | |

| Or: In the Wilderness of the Great Northwest | 1.25 |

THE PAGE COMPANY

53 Beacon Street Boston, Mass.

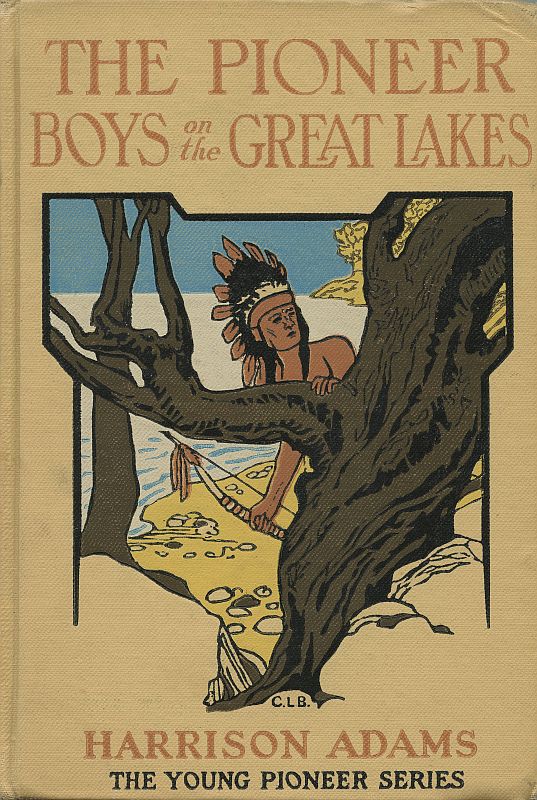

OR: ON THE TRAIL OF THE IROQUOIS

Illustrated and Decorated by

CHARLES LIVINGSTON BULL

THE PAGE COMPANY

BOSTON ![]() PUBLISHERS

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1912, by

L. C. Page & Company.

(INCORPORATED)

————

All rights reserved

First Impression,

September, 1912

Second Impression,

May, 1916

THE COLONIAL PRESS

C. H. SIMONDS & CO.

BOSTON, U. S. A.

To My Young Readers: Many of those among you who have read the first volume of "The Young Pioneer Series" may be pleased to again make the acquaintance of the two border lads, Bob and Sandy, as well as others who figured in the earlier tale. Among these might be mentioned the Irish trapper, Pat O'Mara; Kate, the pretty little sister of our two heroes; Blue Jacket, a young Shawanee warrior, destined later to become famous in history; and Simon Kenton, perhaps the best known among the friends of Daniel Boone.

In this new story concerning the adventures of David Armstrong's boys I trust that you will find much to interest you. It is my earnest hope that such lads as read these stories of daring deeds along the frontier, in those early days of the history of our country, may not only find them intensely entertaining, but instructive as well.

I have tried to show what a sterling type of character, even in young boys, the stern necessities[vi] of those perilous days produced. Self-reliance was absolutely needed in order to successfully cope with the multitude of dangers by which the pioneers of the Ohio and Kentucky border were surrounded.

And, when you have finished the present volume, I can only hope that you will agree with me in saying that Bob and Sandy were splendid specimens of undaunted boyhood, and a credit to their Scotch ancestry. I also trust that you will be eager to meet them again at no very distant time in other fields of daring, whither the roving spirit of Sandy, who has taken Simon Kenton as his ideal hero, may, in company with his brother, be tempted to rove.

Harrison Adams.

August 10th, 1912.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PAGE | |

"'Keep against the rock, all!' said Kenton, who was in the lead" (See page 261) |

Frontispiece |

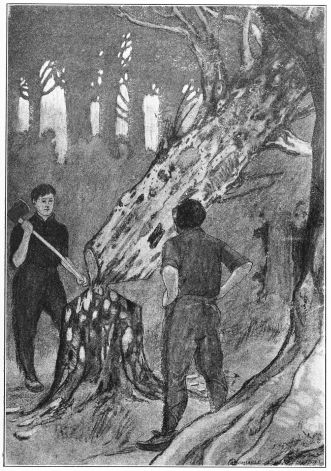

"'Whoop! there she goes!'" |

40 |

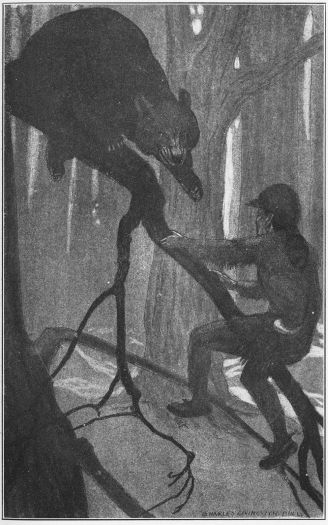

"The bear all the while kept on creeping out closer and closer" |

56 |

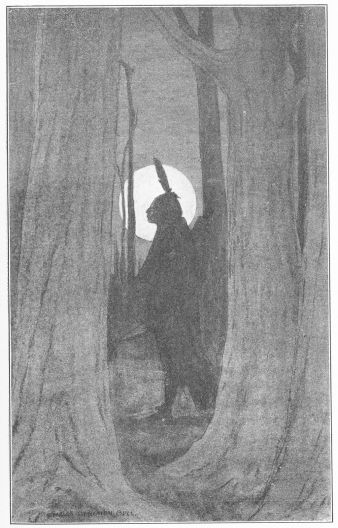

"Plainly marked against the face of the harvest moon, they could see the head and shoulders of an Indian brave!" |

174 |

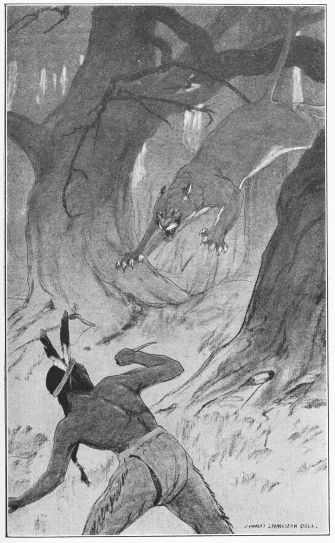

"The boys saw the sheen of his satiny sides as he sprang" |

186 |

"Dancing as they circled the flames" |

222 |

"Hark! Bob, what can all that shouting mean?"

"I'm sure I don't know, Sandy."

"It comes from the other side of the settlement, doesn't it?"

"True enough, brother; for you see the wind carries the sounds; and that is now in the west."

"Oh! I wonder what it can be; and if it means trouble for us, after all these months of peace!"

The two Armstrong boys, Robert and Alexander, who usually went by the shorter names of Bob and Sandy, stood resting on their hoes[2] while listening anxiously to the rapidly increasing clamor.

In the clearing close by stood the cabin of the Ohio settler, David Armstrong. The time was close to early fall, at a time when the strained relations between England and her American colonies had almost reached the breaking-point. But away out here, far removed from civilization, the hardy pioneers were only concerned regarding possible uprisings of the red men; and the widening of their fields, where corn might be cultivated profitably, and tobacco grown.

Early in the preceding spring the Armstrong family, consisting of David, his gentle wife, Mary, the two lads, now fifteen and sixteen years of age, and a young sister named Kate, had left their Virginia home to dare the unknown perils of the wilderness in the hope of bettering their condition.[1]

During the long summer, now drawing to a close, the dozen or more families constituting the little settlement on the bank of the Ohio had been joined by a number of new arrivals, so that by degrees they formed a strong colony.

Some of the fears that had oppressed the [3]more timid of the first settlers now began gradually to vanish, as they saw their numbers increasing, with a corresponding addition to the fighting men of the border post.

Daniel Boone had been an early friend of these Ohio settlers. He it was who had really piloted them to this fair site for a town, on the hill which afforded a magnificent view up and down the beautiful river.

Taking the advice of the famous pioneer, a strong blockhouse had been built as soon as possible. This was completely surrounded by a high and stout palisade, behind which the defenders of the place might find shelter from the enemy in case of an attack.

Thus, even while peace seemed to be hovering over the section, these cautious settlers were constantly prepared for any Indian uprising; and there was even a code of signals arranged, whereby those most remote from the central station were to be warned in case of need.

Twice during the summer Daniel Boone had favored them with brief visits, while on his way back and forth between the distant Virginia plantations and his own settlement far down in the heart of Kentucky.

But Boone had little time for visiting that[4] particular season. While the Armstrongs and their neighbors were enjoying a comparatively peaceful summer, the reverse was the rule around the settlement that had been pushed far out on the frontier line and located at Boonesborough.

Enraged by the boldness of these pioneers, the Shawanees, aided by some of the Delawares, and even Cherokees, made desperate efforts to wipe out the gallant little bands that had been drawn to the outposts of civilization by the prospect of the rich land.

Rumors reached the Ohio settlers from time to time of the serious difficulties their fellow settlers were encountering. These served to keep them on their guard, so that they did not fall into a false sense of security.

Whenever Bob and Sandy Armstrong went into the great forests to seek game, or discover likely places where their traps might be set to advantage in the approaching autumn, they were always warned before leaving home to keep constantly on the watch for Indians. If they met with one or more red men they were never to fully trust any professions of friendship, for the settlers of that day did not have a high opinion of an Indian's word.

These two lads were fairly well versed in the ways of woodsmen. They had always been accustomed to roaming through the forest after game; and, besides, they had received many a hint concerning the secrets of the wilds from a genial Irish trapper, named Pat O'Mara.

This worthy was in a measure possessed of the same unrest that caused Daniel Boone to keep almost constantly on the move. In the case of O'Mara, however, it was simply a desire to see new sights, and encounter novel perils, that caused him to wander through unknown countries, rather than any keen longing to open up rich farming lands to civilization.

Occasionally the Irish trapper dropped in unexpectedly at the Armstrong cabin; but after a few days' rest his uneasy spirit would again cause him to disappear.

This very morning, while they worked in their little patch of ground, Bob and Sandy had been talking about their quaint Irish friend, and wondering where he might happen to be at that time, since they had not seen him for over a month.

When the new settlement was in its infancy the Armstrong boys, feeling that conditions had changed, began to alter their dress. It was one[6] thing to be living in Virginia, not so very far from the sea coast; and quite another to be hundreds of miles inland, beyond the great chain of mountains that served as a barrier between them and the oppressive tax collectors of the king across the water.

The homespun woollen garments gave way to those which nearly all hunters and forest rangers of that day delighted in. Thus, while both lads boasted of tanned buckskin tunics, and nether garments, fringed and ornamented with colored porcupine quills, besides real Indian moccasins, after the manner of the attire worn by Daniel Boone, Simon Kenton and the witty Irish trapper, Bob also owned a cap made of coonskin, with the tails dangling down behind; while his brother's was fashioned from the cured skins of gray squirrels.

They had, of course, left the outer garments at the cabin when starting out, that morning, to accomplish a little hard work in the fields that had been planted earlier in the season, for the day was quite warm.

Besides the sound of the ax, or it might be the crash of a falling tree, there were not many loud noises heard as a rule about the settlement. Sometimes a dog might give tongue as[7] he chased after a rabbit that had ventured too near the borders of the colony; again, a proud rooster, that had been carried so carefully over these hundreds of miles of rough country to his new home, would wake the echoes by his clarion crow. It was a busy time for the settlers, and even the older children were compelled to do their share of labor in these first few months on the Ohio.

So it can be easily understood that, when the Armstrong lads heard that constantly increasing series of loud shouts, they felt the blood leaping through their veins both in curiosity and alarm.

Sandy, always impulsive, threw his clumsy hoe to the ground, and, jumping over to the adjacent tree, against which their flint-lock muskets leaned, caught up his own weapon with trembling fingers. (Note 1.)[A]

Bob was the more composed of the two, and it was his voice that now restrained his brother.

"Wait, Sandy," he said, "we are not so far off but that we can reach the cabin quickly."

"But, listen to all that noise, Bob," returned the other, fingering his gun eagerly. "Surely something has happened. Perhaps another [8]tree has fallen the wrong way, and this time done worse than what happened to our father."

The matter to which Sandy referred had been an unfortunate accident whereby David Armstrong had barely escaped with his life. A tree he was chopping had by some means twisted around in falling, so that the settler was caught under the heavy limbs. Only by what seemed a miracle had his life been spared. As it was, he still had an arm in a sling, and was unable to keep up the work he had planned, so that a double duty devolved upon his sons.

"No, I don't think that can be the trouble," continued Bob, slowly. "I heard no crash of a tree. Besides, I fear that there is a note of alarm in the cries; it is as if men were answering each other. There! that time I could almost hear what was being shouted, only the breeze changed a second too soon."

"Could it be Daniel Boone who has come, or perhaps that young ranger, Simon Kenton, whom you and I liked so much when we saw him long ago?" suggested Sandy, with new eagerness; for, to tell the truth, he had greatly admired Kenton when the young friend of Colonel Boone visited the new settlement, and he secretly aspired to follow in his footsteps.

"No, I am afraid it cannot be that," Bob went on, soberly. "They might shout in that case; but there would be joy, and not fear, expressed. Hark! there it rises again! You have keen hearing, Sandy; did you not make out what our neighbor, Peleg Green, was calling then?"

Sandy turned a pale face toward his companion. These two boys had been through numerous perils in common, and were possessed of a great measure of courage; but, after all, they were only half-grown lads, and the sudden coming of this unknown peril filled them with dread.

"I am not sure, Bob," he replied, with quivering lips; "but I believe I could catch something that sounded like—Indians!"

His brother nodded his head at these words.

"I did not like to say so, for fear I might have been mistaken; but it sounded like that to me," he said, gravely.

Now it was Bob who dropped his hoe, and stooped to possess himself of his gun. Carefully he looked to see that the priming was in order, since everything always depended upon a small pinch of powder being in the pan when the time for firing arrived. The flint never[10] failed to strike sparks; but, lacking powder, these would be of no avail.

"Had we not better run for the house?" suggested Sandy, glancing over across the field toward the cabin, where the smoke arose from the clay chimney, the whole forming a peaceful scene in the sunshine of that late summer morning.

"They have not heard the sounds yet, I think," said Bob, as he failed to note any signs of excitement around the log cabin; "and it would be cruel to frighten mother, if there is no need. Let us wait a bit longer, Sandy. We can easily cover that little distance if there is necessity."

So the boys continued to stand there, gripping their guns, and waiting. Meanwhile it can be readily understood that both lads turned anxious eyes in all directions.

"It seems to me the shouts are not so loud as before," said Bob, presently.

"That might be because the running men have reached their homes," quickly remarked his brother.

"Perhaps we had better go to the cabin. We can say we came in for fresh water, if mother wonders at seeing us. After all it may[11] amount to nothing;" but, hardly had Bob Armstrong completed this sentence, than a new sound came to their ears that sent them running like mad in the direction of the humble home in the clearing.

High above all else came the harsh notes of the alarm bell that had been hung in the blockhouse to give warning of sudden impending danger!

[1] See "The Pioneer Boys of the Ohio."

[A] The notes will be found at the end of the book.

"Look! there is father coming out! He has heard it now!" gasped Sandy, as he ran.

"And with poor little mother close behind him, waving her arms to us to hurry. But where can Kate be, do you think?" asked Bob, as a sudden suspicion came flashing into his mind.

"Perhaps at the spring. She often sits there, and plays. Surely she could not be in the cabin, and fail to follow mother," his brother declared.

"Keep straight on, and I'll go to see!" called Bob, suddenly turning aside from the straight course they had been pursuing.

Sandy hesitated, for he wished to accompany his older brother; but, during their many hunts, he had come to look upon Bob as the leader, and gradually fallen into the way of obeying any instructions the other might see fit to give. So he continued on to the cabin, where his parents were waiting so anxiously.

Mary Armstrong had darted back into the large front room, and now once more came into view, carrying the settler's trusty gun. Though his left arm was still in a sling, David Armstrong gripped the weapon with determination written on his sun-browned face. In defence of his loved ones he would forget his injuries for the time being, and, if need be, fight desperately.

Meanwhile, what of Bob?

The spring from which the Armstrongs secured their drinking water bubbled up from the mossy ground under the trees at some little distance from the cabin. It was reached by a circuitous path, well beaten from frequent pilgrimages to and fro.

Jumping over bushes that intervened, for he was too eager to follow the winding path even when he struck it, Bob quickly came in sight of the spring. His heart was almost in his throat as he discovered the well known sun-bonnet of his pretty sister, Kate, hanging to the bush that overspread the spring; but failed to see the slightest sign of the girl.

Cold with the fear that oppressed him, he continued to advance. What if Kate had already been carried off by some wandering red[14] man? With the vast wilderness stretching all around for hundreds of miles, how would they ever know where to look for her?

"Kate! Oh! Kate!" he called, stopping short in his suspense to listen.

Then, to his great delight, a voice answered him; and the girl arose from a shady nook where she was accustomed to amuse herself.

Apparently she had paid no attention to the brazen sound of the alarm bell, being so wrapped up in her play. But, when Bob sprang to her side, and caught one of her hands in his, the girl's face grew white with fear.

"Oh! what is it, Bob?" she cried. "What has happened? The bell—I didn't notice that it was sounding! Is there a fire? Has any one been hurt like father was?"

"It must mean Indians!" answered Bob, as he hurried her along.

After that dreadful word had passed his lips there was no further need of urging. Kate's feet seemed shod with fear, and she even led him in the race for the cabin. There she was enfolded in the motherly arms and hurried within, to be hastily burdened with several small packages in case they were compelled to flee for safety to the blockhouse.

David Armstrong and the two lads stood without, guns in hand, listening. The bell had now stopped its wild clamor; but they knew that if it again burst out it would mean the worst. And thus, with every sense on the alert, they waited.

While peace had so long hung over the favored settlement on the Ohio, those who composed the little colony knew well what an Indian attack must signify. True, few if any of them had had more than the one experience when the pack train had been assailed in the night while they were on the trail; but they were not apt to forget the fierce whoops of the savages, on that occasion, which had been ringing in their ears ever since.

David had built his cabin after the most approved fashion known among pioneers of that perilous time. The walls had loopholes between the logs in certain places, where guns could be thrust out and fired into the faces of advancing foes. Even the small windows were secured with heavy shutters, fastened from within, so that it would require considerable skill and labor to effect an opening, should the inmates be besieged.

But, of course, it was not the plan of David[16] and his fellow settlers to remain thus isolated, if an opportunity came whereby they could gather in the blockhouse, which was always kept prepared for the reception of the colony.

Mary was now busying herself in closing and fastening these shutters. Bob sprang to assist his mother, ever mindful of her comfort, for he was a thoughtful lad at all times. Impulsive Sandy had just as warm a heart, but was more inclined to be careless and short sighted.

Then, without warning, once more that fearful sound broke forth! The bell was giving out its second call, which meant that every soul within hearing would do well to hasten without delay to the central point.

Perhaps, after all, it might prove to be a needless alarm; but, under the circumstances, no one could take the chance of being caught napping. For aught they knew those cruel Shawanees had finally overcome the valiant defenders of far distant Boonesborough, and, determined to wipe out every settlement west of the Alleghanies, were now advancing north to the Ohio River region with their victorious bands.

"Wife, that settles it!" said David Armstrong,[17] firmly; "we must go at once to the fort!"

Each of them knew what was to be done. They had talked this thing over on more than one occasion, and arranged a system that was to be followed out in case of need.

The heavy puncheon door was closed, and locked with a ponderous padlock that had been carried into the wilderness when they emigrated from their former Virginia home. This being done, the little party started on a run across the open field.

How gloomy, and filled with mysterious perils, did that dense forest seem now! It was so easy to people its aisles with creeping, treacherous foes, armed with bows and arrows, with guns sold by the French traders to be used against the English-speaking colonists, together with tomahawks and scalping knives.

And, when they had entered among the tall trees that grew so close together, how every slight movement along the trail made them quiver with sudden dread, in the belief that they were about to be confronted by a painted horde of Indians, seeking their lives!

The blockhouse, fortunately, was not very far distant. When they began to catch glimpses[18] of it through the trees the hopes of the Armstrongs once more mounted upward.

By now they had overtaken other fugitives, also making for the safety of the central point, and laden with the most precious of their possessions, which consisted for the most part of some family heirloom which they dreaded to have go up in flame and smoke, if the savages put their deserted cabins to the torch, as was their universal custom.

When they reached the palisade they found an excited crowd. The women and children were hurried inside as fast as they arrived; while the defenders of the post clustered near the gates, engaged in anxious communion.

"Who saw the Indians?" asked David, always seeking information; and both of his boys hovered near, with ears wide open to catch every word that might be dropped.

Anthony Brady, who exercised something of the characteristics of a commander among the settlers, by virtue of his age and experience, made immediate answer.

"Old Reuben Jacks, the forest ranger, spied the bloodthirsty villains," he said. "He came first to my cabin, which is further away than the[19] rest. Then, as we ran, we shouted warning, and others, who heard, took it up. Here he comes now. Ask him how many of the red scoundrels he sighted, neighbors."

The man in question was clad in greasy buckskin garments. He had no family; but stopped with different persons whenever he came to the settlement. But, after the manner of the Irish trapper, old Reuben could not long remain in one place, and thus he spent most of his time roaming.

David quickly cornered old Reuben. The forest ranger was a quaint fellow, who carried one of those long-barrelled rifles which were so deadly in the hands of a good marksman. He had several rows of nicks on the stock, and the boys had always been curious to know whether these signified the various wild animals, like bears, and panthers, and wildcats, that he had shot with the weapon, or something perhaps more terrible. But Old Reuben would never tell.

"Where did you see the Indians, Reuben?" asked David, as others of the men began to cluster around, filled with curiosity to know the worst.

"I reckons as how 'twar 'bout three furlongs[20] t'other side o' Cap'n Brady's cabin I see 'em," replied the old ranger in a mumbling tone, due to the absence of teeth in his jaws.

"How many were there?" continued Mr. Armstrong.

"I see three before I turned and run," Reuben answered. "But the bushes was shakin' like they mout 'a' ben a host more a'comin'. They was armed with bows an' arrers, an' I dead sartin saw a scalp hangin' at the belt o' one on 'em."

Bob and Sandy exchanged horrified glances at hearing this. They had themselves passed through quite an experience with the hostile Indians early in the season, when one of the brothers was captured and carried away to the village of the Shawanees, from which he had finally been rescued, after considerable peril had been encountered.

To hear that Indians had been seen so close to the settlement caused a thrill to pass through the heart of the boldest man; and the hands that clutched their guns tightened convulsively on the weapons.

"Were they Shawanees, Reuben?" David continued to ask.

The veteran ranger shook his head, with its straggly gray hair that fell down on his shoulders from under the beaver cap.

"Delaware, I reckons," he said, simply; and they believed that so experienced a woodsman could not be mistaken, for there were many characteristics that distinguished the different tribes, even among the famous Six Nations or Iroquois. (Note 2.)

"Are all here?" asked Captain Brady at this juncture; for they could no longer see any sign of new arrivals hurrying toward the blockhouse.

A hurried count assured them that all families had reached the stockade, with one exception.

"The Bancrofts are missing!" cried one man.

"And their clearing is almost as far away as mine! This looks bad, men!" said Brady, with a grave expression on his set features.

"Something ought to be done, it seems to me," remarked David; for the family in question had been among the first dozen seeking new homes on the Ohio; and between them and his own little brood there had always existed more or less friendship.

"Who'll go with me ter look 'em up?" demanded old Reuben, hoarsely.

Every man present signified his readiness to be of the rescue party; but Captain Brady, of course, would not hear of such a thing.

"It would weaken our defence!" he declared. "We must hold this stockade above all things. Take four men if you wish, Reuben, but no more. And be careful lest you run into an ambush. These savages are treacherous at the best. They would strike you in the back if the chance arose. And if so be you have to shoot, make every bullet tell!"

Sandy pushed forward. He really hoped that the old ranger would pick him out as one of those who were to make up the rescue party. Always reckless, and fairly revelling in excitement, Sandy would have gladly hailed a chance to undertake this perilous adventure.

"Wait!" called out David Armstrong just then. "Perhaps, after all, it may not be necessary to go. Look yonder, Captain Brady, and you will see that the Indians are even now coming out of the woods!"

These words created a new spasm of excitement. Turning their eyes in the direction David had pointed, the gathered settlers saw[23] that he indeed spoke the truth; for several painted figures had just then issued forth from the shelter of the fringe of forest, and started toward the stockade!

Some of the more impetuous among the settlers began immediately to draw back the hammers of their muskets; and one man even threw his gun to his shoulder, as if eager to be the first to fire at the Indians.

But David Armstrong immediately pushed against him, so that his purpose was frustrated.

"What would you do, hothead?" demanded Mr. Armstrong. "They are so far away that your ammunition would only be wasted. Look again, and you will see that there are only four in all. Besides, they have their hands raised in the air, with the palms extended toward us. That means they would talk. It is the same as if they carried a white flag in token of amity. Let no one fire a shot."

"But at the same time be on your guard against the treacherous hounds, men!" called out Captain Brady, himself the most inveterate hater of Indians in the entire colony, and never willing to trust one who carried a copper-colored skin.

Slowly the four red men advanced, continuing to hold up their hands. Evidently they wondered at seeing so great a number of armed whites clustered before the stockade. And the clanging of the bell must have bewildered them, since possibly it was the very first time such a sound had ever been heard by any of the quartette.

"We should not allow them to come too near," one man suggested, cautiously.

"True," called out Brady. "And an equal number of our men should advance to meet them. Armstrong, do you and Reuben, together with Brewster and Lane, step out. We will cover you with our guns. They have laid their bows and tomahawks down on the ground; but look out for treachery. Should you hear me shout, drop down on your faces, for we will sweep them out of existence with one volley!"

The two boys watched the little squad meet the four Indians, and enter into a powwow with them. Much of the conversation had to be carried on through gesture, since only old Reuben could understand the Indian tongue. But it was evident that the newcomers meant to be friendly, and were not the advance couriers of a band bent on burning the post.

Presently David beckoned to Captain Brady, and, as the other approached, he observed:

"They do not mean us any harm. On the contrary this young chief, who says his name is Black Beaver, wishes to trade some skins he has for tobacco. They have been south in Kentucky attending a grand council, and are on the way home to their village. He also wished to secure a small amount of meal if we can spare it. And, Captain, since we wish peace with all the tribes, I have promised to obtain these things for him."

When they heard this the men set up a shout, such was the great relief they experienced after the recent scare. Still, the cautious Brady warned them against being too positive.

"How do we know whether they are deceiving us?" he said, coldly; for he could not bear to be friendly with any Indian. "Perhaps they are even now carrying the scalps of our neighbors, the Bancrofts?"

"Not so, Captain, you wrong them," said David, hastily; "for yonder come those you mention, and apparently none the worse for their delay in starting."

After that there was no reasonable excuse for prolonging the matter; and so by degrees the[27] settlers made their way back to their various homes. The Indians were treated well, and sent on their way with a supply of tobacco and a measure of meal, which latter David Armstrong himself supplied.

But little work was done the balance of that day. The result of the fright occasioned by this, the very first ringing of the alarm bell, made every one more or less nervous. Mrs. Armstrong would not even hear of the two boys starting out to hunt in the afternoon, as they had planned.

"We'd better put it off till to-morrow, Sandy," remarked Bob, when he saw how the recent excitement had affected his mother's nerves.

"I suppose so," replied the younger lad, with regret in his voice. "But I had just set my heart on trying to find that bee tree. We saw the little fellows working in Kate's flower garden, and flying off with their honey. Just think what a fine thing it would be, Bob, if we could learn where their storehouse is, and cut down the tree! Wouldn't mother's eyes just dance to see the piles of combs full of sweetness, perhaps enough for the whole winter?"

"That's a fact," admitted Bob, his own eyes[28] shining with eagerness as Sandy thus painted such a pleasant picture. "But it will keep, I guess, till to-morrow. We ought to get done with our task early in the day, and then for the woods. You know there is not a great stock of meat handy, except that jerked venison that neither of us like very well. I'd enjoy something like a saddle of fresh venison myself."

And so the more impulsive brother found himself compelled to bow to circumstances, always a difficult task with Sandy.

During the afternoon the young pioneers busied themselves in various ways, for there were always plenty of things to be done—water to be carried from the spring, wood for the fire to be cut and hauled close to the door, some of the first pelts which the boys had taken in their rusty traps to be attended to in the curing; the garden to be weeded; and so it went on until the descending sun gave warning that another night was close at hand.

Sandy had taken an hour off to go fishing in the near-by river. As usual he brought back enough of the finny prizes to afford the Armstrong family a bountiful meal that night. From woods and waters they were accustomed to take daily toll, as their needs arose; nor was[29] there likely to be any scarcity of food so long as hostile Indians gave the new settlement a wide berth.

Bob came upon his brother as he was returning to the cabin with a bucket of water. Sandy was almost through cleaning his fish, and the older boy naturally stopped a minute to comment on their fine size.

"I was just thinking, Bob," remarked the worker, with a shake of his head, "that perhaps we might see those same Indians again some fine day."

"What makes you say that?" asked the older lad, quickly; for he knew that Sandy must have something on his mind to speak in this strain.

"I think I feel a little like Captain Brady does about Indians," Sandy replied, "and that they are treacherous. Somehow, I just can't trust them, and that's the truth of it."

"Oh! but how about Blue Jacket? Didn't he prove that he was a true friend to us?" demanded Bob.

The young Indian to whom he referred was a Shawanee brave who had been wounded in the fight the settlers had had just before arriving at the river. The boys had found him desperately[30] hurt, and had cared for him, even saving his life when the irate Captain Brady wanted to have the "varment" killed as he would a snake.

In return Blue Jacket had assisted in the rescue of the Armstrong boys who had fallen into the hands of the Indians.

"That's true, Bob," responded Sandy, readily enough. "Blue Jacket is our friend, but he's the only wearer of a red skin that I would trust. Now, of course, you're wondering what ails me. I'll tell you. I didn't like the way that young Delaware chief looked at our pretty little sister, Kate!"

"What's that you are saying?" demanded Bob, frowning.

"I saw him, if you didn't," continued Sandy, stubbornly. "He kept looking at her every little while even as he talked; for, you know, some of the women and girls came out of the stockade to look at the Indians. I tell you plainly that my finger just itched to touch the trigger of my gun when I saw him staring at Kate like that."

"But—he walked over here with us to get the measure of meal father promised to give him, without accepting any pay?" Bob went on,[31] as if hardly able to credit the grave thing his brother was hinting at.

"Yes, and I kept just behind him all the time," Sandy went on, "with my gun in my hands. I think he noticed me after a while, for he stopped looking. But I wouldn't trust that heathen further than I could see him."

"Well, they have gone away," said Bob, as though that settled it.

"How do you know that?" questioned Sandy.

"Secretly, acting under orders from Captain Brady, old Reuben followed them for three miles, keeping himself hidden all the while. He reported that they had surely kept straight on, secured a canoe just where they said they had hidden one, and paddled across the river, landing on the other shore, and disappearing in the forest."

"But Black Beaver plans to come back some day," Sandy continued, as he arose; "I could see it in his eyes. And I mean to warn mother, so that she can keep Kate from wandering away from home so much. If ever I see that Delaware chief sneaking around here it will be a bad day for him."

"We called them Delawares, but old Reuben[32] says now he made a mistake, and that they belong to the Iroquois. He told me that Black Beaver was a chief among the Senecas, and that his home was far away toward the Great Lakes."

"That may be so," remarked the unconvinced Sandy, starting toward the cabin, for evening was not far away, and he already inwardly felt clamorous demands for the appetizing supper that would soon be on the fire. "But even if he lives hundreds of miles away he can come back, can't he? He has made the journey once, why not again?"

Bob knew that, when once his brother got an idea into his head, argument was next to useless; so he wisely let the matter drop. He himself was not altogether convinced that they had seen the last of the proud young chief, though he hardly anticipated that it would be Kate's pretty face that might draw Black Beaver south again.

Many of the settlers passed an uneasy night; but there was no alarm. Talking the matter over among themselves, some of the men had arrived at the conviction that these representatives of the Iroquois may have been attending one of those great meetings which were being[33] engineered by the Pottawottomi sachem, Pontiac, looking toward a combination of most of the various tribes, by means of which the French in the far North would be assisted, and the English settlements through Ohio, Kentucky, and along the Great Lakes be wiped out.

If this were indeed the truth, then Black Beaver had professed a friendship that he really did not feel, since he must have been forming some league with the warlike and merciless Shawanees, under such leaders as the detested renegade, Simon Girty, of whose cruel deeds history has told.

When the morning finally arrived without any sign of trouble, even gentle Mary Armstrong seemed to have recovered from her nervousness. She assented to the wish of the boys to go forth, and see what they could do in the way of securing fresh food. Before leaving, Sandy cautioned his mother about Kate, for he could not forget the covetous looks which the painted young chief had cast toward his pretty little sister, child though she was, being not more than twelve years of age.

"Be sure and fetch an ax along, Sandy," said Bob, just as they were ready to start forth,[34] with guns fastened over their shoulders by means of straps. "But, if you can help it, don't let mother see you. She would think it strange that we carried such a thing on a little hunt for a deer."

"But what if we succeed in locating the bee tree, and cut it down; how are we to carry the honey home?" asked Sandy.

"Time enough for that when we have won out," replied Bob, with a laugh. "Besides, I don't think we'll be more than a quarter, or at most a third of a mile away from home, unless the little insects are hunting at a longer distance than they generally do, as Pat O'Mara told me."

"Have you got the sugar and everything along?" questioned Sandy.

"Of course. I'd be a pretty chap to go off unprepared, wouldn't I? Now, watch your chance, and sneak the ax off. We'll surely need it to chop the tree down,—if we find it," Bob concluded.

But his sanguine brother never doubted in the least that success was bound to attend their efforts. He went into everything he did with the same enthusiasm and confidence.

Ten minutes later the boys were in an open[35] glade not a great distance away from the Armstrong cabin. Here flowers grew in profusion, even at this late day in the season; and Kate was in the habit of coming out to pick great bunches of the pretty posies, for she loved to see them around the humble cabin, brightening things with their color, and sweetening the atmosphere with their perfume.

Even in those days the methods of bee hunters did not differ very much from those which are in vogue in the woods to-day. The Irish trapper had posted the Armstrong boys as to the way in which a bee tree could be discovered, once busy little workers were found loading up with honey in the flowers or blossoms.

First of all the boys hunted until they discovered where some of the wild bees were busily engaged. Honey was not so plentiful at this particular season of the year; and, when Bob made a little sirup out of some yellow sugar he had been wise enough to fetch along, a bee was quickly attracted to the feast.

When he had loaded himself down with the spoils, and was preparing to fly away, Bob dextrously caught the little fellow. Taking care not to be stung he succeeded in attaching a long white thread to the bee's body, in such a way[36] that it would not interfere with his flying, yet could be seen for quite a distance.

Then the captive was released. As is universally the case, the bee arose in the air, and made a straight fly for the hive! That is where the phrase "a bee-line" originated.

"Watch him now, Sandy!" called Bob, as he liberated the prisoner.

"All right," answered his brother, eagerly. "I can see him still; and how he does spin along. There, he has disappeared now, right beyond that big poplar yonder. Do we go there next time, Bob?"

"Yes," came the reply; "that gives us a start, and will bring us just so much nearer the hive. Then we must catch another bee, and repeat the job. And, as we may not find as many of them, once we enter the woods, we will put several in this little bottle I've brought along with me."

This was easily accomplished; after which they walked over to where they had obtained the very last glimpse of the laden worker.

"We've got the line now," remarked Bob; "and can even go further into the woods, keeping on a straight road. But, for fear that we[37] may overshoot the mark, suppose we make another trial right here."

"Just as you say, Bob," returned Sandy. "You got Pat to tell you lots of things he wouldn't repeat for me. I wonder could it be that leaning tree through there. Seems to me that might be a fine old hive, for it looks hollow enough."

"But you remember Pat said they don't often select a dead tree. It might blow down, and spoil their stock of honey," his brother went on to say.

"But they do find a hollow, don't they?" Sandy inquired.

"Yes; usually the top of a tree that has a hole in it, or a big limb. They are wise enough to know that the rain must be kept out, and also that certain wild animals are mighty fond of honey. Now, here goes, Sandy. Watch close—there!"

Again Bob cast the gorged prisoner free, and the little insect, after several vain efforts, managed to mount upward on sagging wings and make off.

This time as before they marked the last appearance of the laden honey bee, and then a third trial was made. When a fourth and a[38] fifth drew them still deeper into the forest Sandy began to grow much excited. He kept looking all around him while his brother carried out the important operation of coaxing the bee to accept a cargo of sugar sirup in the place of the scarce nectar in the flowers.

All at once Bob looked up.

"Hark!" he exclaimed.

Sandy at once made a move as though about to sling his gun around from his back. Then he saw the smile on his brother's face; and, suspecting the truth, cocked his own head in a listening attitude.

"I hear it!" he exclaimed, his whole face lighting up. "Nothing but the hum of a hive of bees could make that noise, Bob, could it?"

"Look up into that sycamore tree and tell me if you can't see them flying around? Those must be the young ones trying their wings. Pat said they came out every fine day, and buzzed about. He told me he had found more than one bee tree just by tracing the sound. Once heard in the quiet forest it can never be forgotten."

"Hurrah! then we've traced the little rascals to their house!" cried Sandy, as he threw his gun aside, and, clutching the ax, stepped forward to strike the first blow toward cutting[39] down the big tree in which the bees had their hive.

Bob did not try to discourage him, for he knew that when some of this enthusiasm had died away his turn at the chopping would arrive.

And sure enough it did; for Sandy gave out before a quarter of the task had been completed, though later on he would recover his breath and show a willingness to go at it again.

Both lads knew just how to chop a tree so as to lay it where they wished, and, having chosen the best place to throw the big sycamore, they kept hacking away with steady strokes, making the chips fairly fly in showers.

"Whoop! there she goes over with a crash!" shouted Sandy, throwing his cap up into the air, as the tall sycamore came down just as they had planned.

He started to dash forward as soon as the tree had struck, eager to ascertain what sort of prize they had drawn in the lottery; but his more careful brother laid hands on him.

"Don't try it!" he exclaimed. "Why, they are so wild just now, they'd sting you to death!"

"But how are we going to get at the honey, Bob?" demanded the younger lad.

"You run to the house, and tell the others the good news. I'll be making veils out of this thin cloth. Then we have the gloves we used last winter. Bring a lot of pails back with you; for I think we'll need all you can find."

Sandy hastened back to the cabin, where he electrified his father and mother and little Kate with the joyful news. They got together every[41] available vessel for carrying the expected spoils; and then Sandy led the way back to where his brother awaited them.

On the trail he was compelled to explain just how they had taken Pat O'Mara's advice with regard to tracing the honey gatherers; and what splendid success had resulted. Kate was singing with delight over the anticipated store of sweets that would reward their skill in locating the bee tree, for, in those early pioneer days, as a rule the only sugar the settlers had was obtained through boiling down the sap of the sugar maple tree in the early spring; or in discovering some secret store of honey in the forest.

Bob had arranged things completely to his satisfaction while his brother was away. Both of the young pioneers donned the veils and gloves, so that the bees might not take a terrible revenge on the destroyers of their home.

Bob had also made a smudge with which he expected to partly stupefy the angry little creatures. Smoke always frightens bees, for they seem to think that fire is about to devastate their hive. Nature influences them to immediately load up with all the honey they can possibly carry, with the idea of taking it to some[42] new retreat; and while in this condition they are comparatively harmless.

Presently Sandy came back to the spot where the others were standing in safety. He had a bucket almost full of broken combs from which the richness was oozing in a manner that set little Kate wild with delight. As for the good mother the sight was undoubtedly a pleasant one for her, since it promised many a delightful treat in the long winter months ahead.

David Armstrong immediately started home with the bucket, so as to empty it, and once more put it into service. Bob was still working there in the midst of the ruined hive.

"And he says there are, oh! ever so many more buckets of better honey than this!" Sandy had cried, as he brought out a second supply, in which the combs were less broken than before, and seemed newer.

"The whole air is filled with the perfume of honey," remarked Mary Armstrong. "It hardly seems right to rob the poor little workers in this way, after they have stored it up so carefully; though we do need it badly, for there will be little sugar in our home except what we make next spring."

"Oh! Bob says there'll be just oceans of it[43] left, spilled on the ground," Sandy went on, "and the bees will get it all, sooner or later. Plenty of time for 'em to seal it up for this winter. They always have ten times too much, and that's why some of it is so old and dark looking. Bob says he is not taking that if he can help it."

"Why, I could smell the honey half way to the house," remarked Mr. Armstrong, as he came up just then. "And, if there happens to be a bear within half a mile of this place, you can depend on it that he'll be prowling around here this very night."

"That was just what Bob was saying, father!" declared Sandy. "He showed me marks on the smooth trunk of the sycamore, where a bear must have climbed up ever so often, as if trying to reach in at the honey that was just too far away for him to steal. And some of the scratches were so fresh Bob says they must have been made only last night."

After numerous trips to the cabin to empty the buckets the pleasant task was finally completed. Bob declared that he had secured about all of the honey that was worth carrying away. There still remained a great store of the sticky stuff; but it was either spilled on the ground,[44] or else so darkened by age that it did not seem worth while carrying it off.

"We'll leave it to the poor little fellows," laughed Bob; "for they're as busy as beavers right now loading up and flying off to another hollow tree one of 'em has found. And I think we're pretty lucky to get off as easy as we did, eh, Sandy?"

Sandy had removed the thin cloth veil that covered his face, and by this action revealed the fact that at least one angry bee had found a way to pierce his armor; for his left cheek was swollen so that his eye seemed unusually small. Some wet clay took the pain out, however, and in due course of time the swelling would go down.

It was not the first time Sandy had felt a sting from a bee, nor did he expect it would be the last. And, when he looked at the glorious fruits of their raid on that big sycamore hive, he forgot that he had suffered in the good cause.

"Well, do we try for that bear to-night, Bob?" he asked of his brother, later on in the afternoon, when he could see once more fairly well with both eyes.

"I think we would be silly not to," replied[45] his brother; "especially since we set the trap ourselves when we cut down that bee tree."

"He's just sure to come nosing around, don't you think?"

"Don't see how any bear could stand back, with all that odor in the air. Besides, it looked to me as if the old fellow might have been paying a visit to that tree every single night for a whole month, there were so many scratches on the bark. So you can just depend on it that he's got his mouth set for honey."

"And then there's another thing in our favor," Sandy went on saying, as he glanced upward toward the heavens, an action that caused his brother to remark:

"I'd wager a shilling that you are thinking of the moon being nearly full to-night, which is a fact. That is in our favor, and, on the whole, I'd be inclined to believe that we may be tasting a bear steak by to-morrow."

"One good thing leads to another with us, Bob. First a prize in the way of gallons and gallons of prime honey, and then, to finish, perhaps a fat bear in the bargain! But, remember, you said I was to have the first shot at the old honey thief, if he does make his appearance?"

"All right," answered Bob, good naturedly;[46] "and I'll keep my word; but if I were you I would go slow about calling names. Please remember that there are some others in the same boat. Only, in our case, we succeeded in getting the spoils; and there we have the better of old Bruin, who climbed that tree so very many times only to have his trouble for his pains."

Of course the lads took their parents into their plans, for it might be their absence would worry the little mother, who sometimes still thought of that wild ringing of the alarm bell, and all it might have meant.

Shortly after they had had their supper, the two lads took their muskets, and passed out into the night. As they had said, it promised to be just a glorious opportunity to carry out such a plan as they had in mind.

The moon rode high in the eastern heavens, being not very far from full. Not a cloud seemed to dim the bright light, so that, for a short distance around them, things looked almost as plain as in the daytime.

As the two boys had done considerable hunting in common there was little necessity for talking things over, or arranging any programme. When the honey-loving bear came along, eager to satisfy his craving for sweets,[47] of course Sandy would wait for a favorable chance to get in a fair shot. And, unless his aim were poor, or some accident occurred to otherwise mar the arrangements, that would wind matters up.

Arriving at the fallen bee tree, the young pioneers quickly decided just where they should secrete themselves. In doing this they exercised their knowledge as woodrangers, for much depended on the direction of the wind.

"It seems to be blowing toward the home quarter," remarked Bob, as they stood there, fixing certain facts in their minds. "That favors us finely, because the chances are ten to one he will come from the other side of the opening made by our felling the big sycamore. So you see he won't be able to smell us."

"How will this place do, Bob?" suggested the younger brother, pointing to what in his mind made a splendid hiding-nook, from which they could peer forth, and see anything that took place just beyond.

"Could hardly be better; and so there is no use for us to look further," Bob remarked. "Pick out your stand, Sandy, where you will be able to shoot best. I'll be satisfied to take what is left."

This was soon arranged, and, having once settled down to wait, they tried to keep as still as though made out of marble. Talking was forbidden, even in whispers; and a cough would very likely have ruined the whole affair, since the bear, if near-by at the time, must have been warned of his danger, and with a "wuff" would turn to rush away.

An hour passed in this way. Fortunately the two lads were good waiters, and had proved this on many another occasion in the past.

Sandy had allowed his thoughts to go out to other scenes, and was even thinking of that fine young frontiersman, Simon Kenton, whom he admired so much, when he felt his brother touch him softly on the shoulder. The contact thrilled him, since it was the signal agreed on to denote that the lumbering bear was coming!

"Listen!" said Bob, his lips placed as close to the ear of his brother as he could possibly get them.

"I hear him! He is over there, just where you said," replied the younger hunter, the words being whispered so low that they could not have been detected six feet away.

"Get ready then—have your gun up, so he won't see the movement. 'Sh!"

Bob said this because he knew that, with that bright moonlight flooding the opening, there must always be a chance that its rays would glint from the metal barrel of a moving musket. And even such a little thing as this might serve to startle a suspicious bear into making a sudden retreat.

The sounds now became more pronounced than before. Some heavy body was undoubtedly pushing through the underbrush, and in such haste as to be utterly unmindful of what noise was produced.

Of course nothing but a clumsy bear could be guilty of such an advance, caution being thrown to the four winds because of that tantalizing odor of honey in the heavy night air,—an odor which was making Bruin fairly wild with eagerness to be at the anticipated feast.

A panther would have crept slily forward, so that not even the rustle of a leaf might betray its presence, and even a buffalo would have advanced with a certain amount of caution; but a bear depends on its sense of smell to give warning of danger, and seldom moves with any degree of care.

Presently Sandy could hear him sniffling at a great rate as he pushed closer. The animal evidently could not understand why there should be such a pronounced odor of honey in the air. Many times had he come to this same spot in the hope of being able to bag some of the bees' store; but always to meet disappointment. But now there must be a great change in the arrangement of things.

Somewhere amid the foliage covering the bushes across the glade the big beast must have stopped, to look in surprise at the fallen bee tree. Perhaps he suspected a trap of some kind, knowing that his mortal enemy, man, had been[51] there lately. But that distracting smell drowned all his caution. Unable to hold out against it any longer, the bear suddenly lumbered forward.

Sandy saw him coming, but held his fire. In the first place the bear was head on, and he wanted to get a chance at the animal's flank, so that he might make sure to plant his bullet back of the shoulder, where he could reach the heart, and so bring his game down with that one shot. Then again, it chanced that there was something of a shadow, which served to partly hide the beast as he advanced.

Straight into the midst of the broken honeycombs did Bruin hasten, grunting in evident delight as he commenced to lick up the spilled sweet fluid, so dear to the heart of every bear.

Sandy managed to repress his excitement to a great extent. He had been hunting so often, boy though he was, that he no longer experienced the same intense thrill that would have almost overwhelmed him a couple of years ago, had he been thrown into such a position as this.

Slowly his cheek dropped down until it rested against the butt of his faithful old musket. Well did he know that the priming was in the pan, and that, when the flint struck the steel[52] sharply, the spark would communicate to the charge, with the result that the bear must be considerably astonished.

Unfortunately, however, Sandy could not see in that deceptive moonlight that a fair-sized twig happened to be just between the muzzle of his gun and the object at which he aimed. Had it been daytime he would have detected this fact, and avoided taking the chances of his bullet being slightly deflected in its swift passage.

The report of the gun was deafening. With his usual impulsiveness Sandy instantly leaped to his feet, giving a boyish shout as he saw the bear kicking on the ground, in the midst of the branches of the fallen tree.

Then, to his utter astonishment, and not a little to his chagrin as well, the dark, rolling object seemed to scramble once more to its four feet, and, attracted by his movements, immediately started to advance directly toward him, growling in the fiercest possible way.

It could no longer be said that Bruin was making a clumsy and slow advance, for, inspired by a sudden rage toward the object from which his painful wound had evidently sprang, the animal was rushing furiously forward.

Bob fired in the hope of checking this advance,[53] that promised to upset all of their fine plans; but just then Sandy, in jumping back, chanced to jostle his brother, so that, even if the second bullet struck the bear at all, it certainly did no great damage. At least his swift if lumbering advance was not materially checked.

"Run, Sandy!" shouted Bob, as he realized that they were now facing an infuriated and wounded beast, with only their hatchets and knives to use in defence of their lives.

Sandy was not slow to take the advice thus given. He sprang away in one direction, while Bob took the other. Just why the bear should have picked out Sandy to follow, neither of the brothers could ever say, though they really believed the old fellow was keen enough to understand which of the fleeing lads had sent that first stinging pellet that bored under his skin, and made him so uncomfortable.

Bob was dismayed when he found that the animal had ignored him, and was chasing Sandy. With his usual generous way of taking burdens on his shoulders, Bob had really hoped to attract the bear; indeed, with this idea in view, he had even made more noise than was necessary, as he floundered along through the bushes.

When, however, he found that he had not been followed, he immediately changed his tactics. From running away he now started to follow after the bear, and, as he thus pushed through the woods, the boy tried to reload his musket, always a difficult task in those days of the primitive powder-horn, when the charge had to be measured out into the palm, poured into the long barrel, and the bullet in its patch of greased cloth pushed down with the ramrod; after which the priming had to be adjusted.

Bob was not making any particularly good headway in reloading, since he could not stay his hurrying steps long enough to do the right thing.

From the noise ahead he judged that Sandy must have succeeded in drawing himself up into the friendly branches of a tree, and that the furious bear was following close on his heels.

At least this would give the fugitive a little time, and perhaps, meanwhile, he, Bob, could come on the scene with his gun, ready to take a hand in the game.

"Hi! Bob, this way!" Sandy was shouting, at the top of his voice, as though his situation was rapidly becoming desperate.

"All right!" answered the one who was pushing along through the brush as best he could. "I'm coming, Sandy! Hold on a little longer!"

A minute or so later he found himself on the scene. Just as he had guessed, Sandy, being hotly pursued, and fearing lest he be overtaken by the angry beast, had on the spur of the moment clambered hastily into the branches of a tree. It was the result of sudden impulse, for surely the boy knew that an American black bear is always at home wherever he can dig his sharp claws into the bark of a tree.

Perhaps Sandy would never fully realize how he came to escape the animal's last rush; but it must have been almost by a miracle. Once among the branches, the boy did not stop an instant. The bear immediately showed an inclination to follow him aloft, and Sandy hardly cared to try conclusions with Bruin in his present winded condition, and with only his hatchet to depend on.

So he had hastily climbed upward. Looking down, he had been dismayed to see that the bear was making quick progress after him. He could hardly go to the top of the tree, and, as a possibility leaped into his mind, the boy started out[56] on a large limb that was some twenty feet or so above the ground.

Bruin did not hesitate a moment when he reached this limb, but started out after the young hunter. It was at that moment Sandy had sent out his appeal for help. He realized that he was in a bad fix, since the bear would either follow until he could reach his intended victim with his sharp claws; or else the combined weight of the two must break the limb, sending both to the ground.

Bob, having arrived under the tree, was making desperate efforts to finish loading his gun, so that he might bring the little drama to a close. But the bear all the while kept on creeping out closer and closer, balancing his bulk with wonderful skill upon the limb.

Sandy was impulsive in his ways; at the same time that bright mind of his was apt to originate many a clever ruse on the spur of the moment, and when desperation pushed.

Bob, keeping one eye anxiously turned upward while he pushed the bullet hastily into the chamber of his gun, saw his brother suddenly back still further away, so that the limb began to bend downward with his weight. The bear halted, as if loath to make any further forward[57] move, and watching to see what his human adversary might be contemplating.

Suddenly Sandy let go his hold of the outer branches. He had seen that he might break his fall by passing through the foliage just below, and was willing to accept the chances of receiving sundry scratches in consequence.

Bob fairly held his breath as he saw this bold action on the part of his brother. The bear crouched closer to the limb above, as though declining to be shaken from his hold. But, when the danger of this had passed, the beast started to back to the trunk of the tree, intent on reaching the ground again as speedily as possible.

Sandy had come through the lower foliage with a great scramble, very much after the manner of a floundering wildcat that had been shot while perched in a tree.

Bob waited only long enough to assure himself that his brother had reached the ground, even in a sadly dishevelled condition. Then he began to add the necessary priming to his gun, for Bruin was already starting to descend to renew hostilities.

Taking several steps forward, Bob arrived at the base of the big beech with its wide-spreading[58] branches. It was evidently his intention to wait for the coming of the bear, and give him a warm reception.

Bruin, in his ignorance of such things as explosives, since his only adventures up to now had probably been with the arrows of the red men, gave little heed to this suggestive action on the part of the young hunter. He kept backing down with all possible haste, anxious to avenge his injuries upon these human foes.

But, after all, Bob found himself mistaken when he supposed that it was up to him to end the big beast. While the bear was still at least ten feet above him, the musket was suddenly taken forcibly from his hands.

"You promised me, Bob, please remember!" cried Sandy.

With his face bleeding from the scratches he had received in his fall, Sandy must certainly have presented a strange appearance just then; but the spirit of the hunter rose superior to any and all discomforts. That bear was his by rights, and he did not mean to be cheated out of his triumph.

Down came Bruin, looking over his shoulder as he dropped, and probably measuring the capacity of these two foes. But he failed to[59] figure on the terrible power that lay in the odd looking stick one of them pointed up at him.

There was a sudden flash, a stunning report, for Bob in his nervousness had overcharged his gun, and while Sandy fell back with a bruised shoulder, the bear dropped like a stone at the foot of the tree. Sandy had clapped the muzzle of the musket close to the animal's ear when pulling the trigger, so that the result was never in doubt.

"Whew!" he exclaimed, as he scrambled to his feet, still clutching Bob's gun. "Did you empty your powder-horn in that charge, Bob? I'll be black and blue for a month after that recoil. But I got him, didn't I? He'll never have a chance to chase a fellow up a tree again. And, Bob, we're going to have that bear steak all right to-morrow, I reckon."

Which they did, sure enough, though, as Bruin was no youngster, it probably required pretty sharp teeth to enjoy the meal.

It was just three days after the strange bear hunt that the boys, on returning from a little trip to see what their traps might contain thus early in the season, found that the home circle had been widened by the coming of the Irish trapper, Pat O'Mara.

He was a jovial fellow, with a fiery red beard, and hair of the same hue falling far below his coonskin cap. His blue eyes generally twinkled with humor; but, for all that, he had long since proved himself a fit companion for such woodsmen as Daniel Boone, Simon Kenton, James Harrod, Jo Daviess and John Hardin, foremost in the list of pioneers who had carved their names on the pages of history by their brave deeds along the disputed border countries.

Pat was delighted to see the two Armstrong boys again, for they had been favorites of his ever since the days when, acting on his advice, David had decided to leave Virginia and cast his fortunes with the bold settlers along the[61] upper Ohio. But wise Bob soon saw that, under all his fun, there was a seriousness about Pat that he could not remember noting before.

The trapper examined what few pelts the boys had taken up to now, and gave more or less advice about curing them to the best advantage.

"As the sa'son grows older the fur wull be thicker," he observed, smoothing the soft pelt of a red fox that had been recently taken. "And, av ye obsarve what I'm tillin' ye, 'tis a better price ye'll recave for the same from the trader, unless by the same token it happens till be a Frinchman ye be d'alin' wid. They do be wantin' to gobble the hull airth, I do be thinkin'."

This was always a subject upon which Pat felt deeply, for he was known to have a bitter prejudice against the French trappers and traders generally. At this time the French were in complete mastery of the valuable fur regions around the Great Lakes, and, being also located far in the south, at the mouth of the Mississippi at New Orleans, it was the announced intention of the companies controlling these half-breed trappers to form a chain of[62] trading posts from Canada to the distant Mexican gulf.

Daniel Boone knew all about this tremendous scheme, and it was partly with the idea of blocking it that he had pushed out so far into the western wilderness, and influenced others to follow his example.

Dangers without number they must face in so doing; but, surely, if the wonderful wide-reaching valley of the Mississippi might be saved for English-speaking people, their efforts would be worth while.

While Bob watched the face of the Irish trapper, he came to the conclusion that Pat must have brought some unpleasant news along with him. This turned out to be the exact truth. As the two boys had now reached an age when they were to be depended on as defenders of the home, David Armstrong only waited until Kate happened to be sent on an errand to a neighbor, when he had Pat recount the matter for the benefit of Bob and Sandy.

There was much talk of a big Indian uprising all through the country between the Ohio and the lakes. Pontiac was again endeavoring to form a coalition of the many tribes, from the Six Nations, or Iroquois, in New York and[63] Ohio, to the Pottawottomies and Sacs in the west, and the Creeks and Shawanees in the south.

Already, in many places, the red men were said to be on the warpath, and a trail of burning cabins marked their passage.

Pat had heard of these things, and, thinking of the good friends who had settled on the Ohio only the preceding spring, he had lost little time in making his way back again to the settlement that was flourishing so finely.

"It wull not be apt till come till ye, right away," he said in conclusion; "but 'tis just as well that ivery sowl be made aware av the danger. Niver belave thot ye are safe from attack here. It do be a foine place to defind, located on a hill as ye are; but remimber that the rids are backed up by more or less av thim treacherous Frinch trappers and traders; and that they are sworn to wipe out ivery English post wist av the mountains."

The news quickly spread until it was known in every home. Men got together and talked it over, trying to so arrange their plans that, in the event of an attack, the defence of the blockhouse would be conducted in the best possible manner.

Scouts were sent out whose business it was to scour the forest many miles around, on both sides of the river. And, should one of these discover that they were threatened with an inroad of the Indians, it must be his duty to hasten to send up a signal of warning.

This was to be in the shape of certain columns of black smoke, which, seen by the next scout, would be repeated, until in this manner the startling news might be received at the settlement hours in advance of the coming of the fleetest messenger.

It was employing the tactics of the Indians to a good purpose.

These precautions having been taken, the settlers went about their daily duties, confident that they would receive ample warning should danger arise, and also that they would be able to give a good account of themselves in battle, did the reds venture to attack the post.

But it was the policy of every man, woman and child, from that time forth, to keep an uneasy eye on the sky line, especially toward the east and west. Men, as they worked in their maize fields, would pause every little while to sweep the horizon with anxious gaze; and, should one of them at any time happen to discover[65] any sign of smoke rising, it was apt to be an anxious moment for him until he had assured himself that the column was a single one, and not triple.

Even such a hovering cloud as this could not keep the two venturesome Armstrong boys from going forth every day. Sometimes they had business along their trap line, for work grew pretty brisk as the season advanced. Then again it might be a hunt that engaged their attention. Whenever they had any extra meat on hand it was their provident habit to dry the same for use in the hard winter months ahead.

As yet the settlers knew not what awaited them, once the snows of winter closed in, for they had never spent such a season on the Ohio. Tales of bitter weather had come to them; but they were hardy souls, and believed that, if the Indians could come through such a yearly experience unscathed, they ought to be able to do the same.

Nevertheless, every good housewife started early to lay in all such extra stores as could be procured. The stock of simple herbs, drying in bunches from the beams overhead in the living room of the Armstrong cabin, testified[66] to the fact that the careful mother was prepared for any ordinary sickness that might arise. And there, too, could be seen various packages of the tough jerked venison, which would sustain life, when gnawed, as the Indians were accustomed to doing when on the trail, though the more civilized settlers preferred to use it in soups or stews.

For two days Bob and Sandy had not been out in the forest save to look after their traps. True, only the preceding day, a fine fat wild turkey had fallen before the gun of Sandy, and been greatly enjoyed; but both lads felt an eagerness to once again go forth on a genuine hunt for larger game.

The tender-hearted and fearful little mother could not forbid them venturing forth, even though she sighed after they had gone, and wiped a furtive tear from her eye. Food was a necessity, and they had no other means for procuring it than in this manner. According to their belief, Providence had stocked these woods with game in order to provide sustenance for the pioneers who must blaze the trail of civilization.

Warned to be unusually careful, Bob and his brother once again wended their way through[67] the mysterious aisles of the solemn forest, which had now become so familiar a field to them. Did they not know nearly every little animal that had its home there; and were they not on good terms with many that they scorned to injure, since their flesh was not wanted for food, nor their fur for trading purposes?

Two hours after leaving home the young pioneers came across the tracks of a deer, and, finding that the trail was fresh, they started to follow. The wind was in their faces, so that everything seemed favorable for stalking the quarry, should they find that the animal was browsing in one of the little grassy glades which they knew were close at hand.

And, true enough, as they thus advanced cautiously, they sighted a noble buck feeding as though all unconscious of danger. Foot by foot the boys crept closer, intent on securing such splendid quarry.

This time it was Bob's turn to fire first, while Sandy held himself in readiness to make sure of the buck if by chance his brother failed.

Bob was looking along the barrel of his musket when, without warning, a shot rang out from a point further away, followed instantly by a second and a third; but the buck, apparently[68] uninjured, leaped off as though about to speed beyond the danger zone.

The instinct of the hunter would not allow Bob to hold back his fire, even though he was startled by this unexpected volley. And, after he pulled the trigger, the buck gave one great leap into the air, to fall a quivering mass on the moss-covered ground.

Both lads hurried forward toward the fallen deer; but Bob felt a quiver of apprehension when he discovered three burly figures hastening to arrive there ahead of them.

"Oh! they are French trappers, Bob!" exclaimed Sandy, though he betrayed not the least symptom of holding back.

"Yes, and we must be careful what we do!" remarked Bob, uneasily.

"But it is your deer, for he fell when you fired!" Sandy declared, stubbornly.

In another minute the brothers had arrived at the spot, to find the foot of a dark-faced forest ranger planted on the dead buck, and three pairs of snapping black eyes looking at them in defiance.

Apparently their right to the game was about to be seriously questioned!

"Keep cool, now, Sandy!" advised Bob, as he felt his brother trembling with indignation because of this bold attitude on the part of the trio of French forest rangers, who evidently believed in the maxim that "might makes right."

"But, Bob, see, they mean to take our game from us!" exclaimed the impetuous Sandy, who could not mistake the intentions of the French trappers.

One of the men was a tall, gaunt fellow, with the eye of a hawk. He seemed to be something of a leading spirit among his comrades. Bob felt that he possessed a cruel nature, and such a man, he believed, would only too gladly conspire with bloodthirsty Indians to surprise the new settlements of the English, and raze them to the ground.

This fellow thrust himself forward, and, scowling darkly, demanded in fairly good English:

"What for you say zat ze game is yours? Haf you not ze eye to see zat aftaire ze first fire ze buck he nevaire run far? And as for zat bullet you send, poof! it haf been waste in ze air!" and with that he snapped his fingers contemptuously, as though that settled the matter beyond dispute.

They were only a couple of half-grown boys, after all, and could hardly hold out against three burly men, accustomed to a strenuous life.

But Sandy was quick to see things; nor did he have the prudence to hold his tongue when he believed he was being wronged. No doubt he had been more or less influenced in his opinion of these French traders and voyageurs by what he had so often heard Pat O'Mara declare—that they were without exception the "scum of the earth, and fit only for treason, stratagem and spoils."

"But see, only one bullet has struck the deer in a place where it would down him—right here behind the shoulder!" he cried, pointing with a trembling hand at the blood on the red hair of the animal.

"Zat is so, young monsieur," said the Frenchman smoothly, and with a mocking bow; "and I assure you it was just zere zat I aim[71] my rifle. Sacre! Andre, and you, Jules, tell me if zis be not one fine shot!"

"But," cried the indignant Sandy immediately, "I tell you that is impossible!"

The tall and ugly Frenchman scowled, and then laughed harshly.

"Say you so, my leetle fire-eater?" he exclaimed. "How it is zat you come to zat conclusion?"

"Because," said the pioneer boy boldly, "if you look you will see that the bullet that killed the buck entered from the right; and we were on that side, not you. So the honor of killing this deer belongs to my brother."

The other Frenchmen evidently understood the point Sandy was making, even though not capable of speaking much English. They grinned, and cast quick glances at the dark-faced leader, as if wondering how he would take this thrust.

The tall trapper scowled savagely, and half raised his empty gun menacingly. But Sandy never gave way a particle. He knew that his gun was still loaded, while, in all probability, those of the others had not been recharged; three shots had sounded, proving that all had taken a chance at hitting the elusive buck.