217

I.—Fons et Origo Mali.

Snugly nestling in a cosy corner of Blankshire—that county which at different times and places has travelled all over England—our village pursues the even tenor of its way. To be accurate, I should say did pursue, before the events that have recently happened—events in which it would be absurd modesty not to confess I have played a prominent part. Now we are as full of excitement as aforetime we were given over to monotony. Nous avons—— No! J'ai changé tout çela.

It came about in this way. I have always till the 25th of September (a chronicler should always be up to dates) been entirely free from any ambition to excel in public. After a successful life I have settled down with my wife and family to the repose of a truly rural existence. "You should come down and live in the country," I am never tired of telling my friends. "Good air, beautiful milk, and, best of all, fresh eggs." I don't know why, but you are always expected to praise the country eggs. So I always make a point of doing it.

Up to September the 25th, accordingly, I extolled the eggs of the country and lived my simple, unpretending life. On that day I read an article in the paper on the Parish Councils Act. I read that now for the first time the people in the villages would taste the sweets of local self-government. The change from fresh eggs struck my fancy, up to that time singularly dormant. I read on, dashing all unknowing to my fate. "It is the duty," I saw, "of every man of education, experience, and leisure in the village who has the welfare of his country at heart to study the Act, and to make it his business that his fellow-parishioners shall know what the Act does, and how the greatest advantage can be obtained from its working." Then my evil genius prompted me to undertake the task myself. I was educated—did I not get a poll degree at Cambridge, approved even by Mr. Charles Whibley as a test of culture? I had experience—had I not shone as a financial light in the City for full twenty years? I had leisure—for had I anything in the world to do? Obviously the occasion had come, and I—yes I—was the man to rise to it.

I bought twenty-nine works dealing with the Act. I studied them diligently section by section, clause by clause, line by line. I referred to all the Acts mentioned. I investigated all the Acts repealed. At the end of it all I felt like a collection of conundrums. But I was not to be denied. One evening, as I was walking through the village, I met Robert Hedger, "Black Bob," as he is always called. He is a farm hand, and for some reason looked upon as a leader of men in the village. I saw my chance, and promptly took it.

"Good evening, Bob," I said. "I've been wanting to have a bit of a talk with you about this Parish Councils Act."

"Well, Sir, and what about that?" Of course he spoke in dialect, but the dialect dialogues are almost played out, so I translate into quite ordinary English. It's easier to understand, and quite as interesting.

"What about it?" said I, with well-simulated surprise. Then I launched into a glowing account of what it would effect. I waxed poetic. The agricultural labourer would come home at night from his work proud in the consciousness of being a citizen. He would breathe a different air; the very fire in his cottage would burn brighter because a Parish Council had been established in his midst. I finished (it was a distinct anticlimax) by saying that I had been carefully studying the Act.

Two days later Black Bob and two of his mates called at my house—a deputation to ask me to speak at a meeting, to explain the Act. I pleaded modesty, and, saying I would ne'er consent, consented. It was a vain thing to have done, and the effects have been startling. But that meeting must have a chapter to itself.

I carnt on airth think what is the matter with me lately. I seems to have lost all my good sperrits, and am as quiet and as mopish as if I was out of a sitiation, which in course I am not, and am not at all likely to be. My wife bothers me by constent inquiries about the comin change on the 9th, but she ort to no, as I noes, that the cumming new Lord Mare is jest the same good, kind, afabel Gent as the noble Gent as is a going afore him, and who ewery body loved and respected, and who allers showed me ewery posserbel kindness. I aint not at all sure as them wunderful Gents as calls theirselves County Countsellers, and is allers a throwing their ill-natured jeers at the grand old Citty, hasn't sumthink to do with it. I'm told as they has acshally ordered one of our most poplar Theaters to be shut up, becoz the acters and actresses is so werry atracktive that they draws a wunderful contrast between them and the sollem Gents as is allers a interfeering in some way or other where they are least wanted.

One of their most wunderful and most conceeted fads is a longing desire to have charge of our nobel Citty Perlice, which, as ewery body knos, is the pride of the hole Metrolypus.

One of the new Lord Mare's private gennelmen has told me, in the werry strictest confidens, that they have all agreed together, Lord Mare, Sherryfs, Halldermen, Liverymen, and setterer, to have the most brillientest Show as has bin seen in the old Citty since the time of Dick Wittington of ewarlasting memory! if its ony for the purpose of driving the County Countsellers, as they calls theirselves, stark staring mad with enwy! And so estonished is the Queen's Guvernment themselves by what they hears on the subjec of the glorious approching Dinner, that they has acshally ordered the werry primest of all their Cabinet lot, inclooding the Prime Minister hisself, and the Lord Chanceseller, and my Lord Spinster, and setterer and setterer, not only to accept the Lord Mare's perlite inwitation, but to take care to be in good time, and not to keep the nobel company waiting as old Mr. Gledstone usued to do in days gorn by.

By-the-by, the present Lord Mare, jest to show his ermazin libberality, acshally arsked jest a few of the County Countsellers to his larst great bankwet larst week, and werry much they seemed to injoy theirselves, and I must say, behaived like reel gennelmen, tho' sum of the speeches, speshally them by Lord Hailsbery and Mr. Richer, must have been rayther staggerers for them to bear.

Prosit.—Best wishes to Mr. Beerbohm Tree for the success of the new piece at the Haymarket. Whatever may be the result, he, personally, is in for a "Wynn." 218

["Of course, you may get the House of Lords to surrender as you get a fortress to surrender, by making it clear that it is encompassed and besieged beyond all hope of deliverance; but that in itself is not an easy task with the garrison that I have described as sure to defend it.... We fling down the gauntlet. It is for you to back us up."—Lord Rosebery at Bradford.]

| Bob Acres | Lord R-s-b-ry. |

| Sir Lucius O'Trigger | Irish Party. |

Sir Lucius. Then sure you know what is to be done?

Acres. What! fight him?

Sir Lucius. Ay, to be sure: what can I mean else?... I think he has given you the greatest provocation in the world.

Acres. Gad, that's true—I grow full of anger, Sir Lucius!—I fire apace! Odds hilts and blades! I find a man may have a deal of valour in him and not know it!... Your words are a grenadier's match to my heart! I believe courage must be catching! I certainly do feel a kind of valour rising as it were—a kind of courage as I may say.—Odds flints, pans and triggers! I'll challenge him directly!—The Rivals.

Fighting Bob's Afterthoughts.

"THE CHALLENGE."

Sir Lucius O'Trigger (the Irish Party). "Then sure you know what is to be done?"

Bob Acres (L-rd R-s-b-ry). "What! fight him?... Odds flints, pans and triggers! I'll challenge him directly!" 219

(Adapted for the Board School Infant Classes.)

A (School-Board) Apple-Pie; B (uilt it); C (ircular) cut it up; D (iggle) directed it; E (xpenses) eat it up; F (orster) fought for it; G (ladstone) got it through; H (ostility) hampered it; I (ntolerance) injured it; J (ealousies) jangled about it; K (indness) kindled at it; L (obb) lightened its costs; M (oney) met them; N (oodles) talked nonsense about it; O (pinion) oscillated concerning it; P (rogressives) prodded it; Q (uidnuncs) querulously questioned and quizzed it; R (iley) raised religious rumpus about it, while R (atepayers) ruefully regarded him; S (ecularism) sneered at it; T (eachers) toiled for it; V (ituperation) vexed it; W (isdom) wondered at it; and X, Y, Z—well, "Wise-heads" are few, and "X" is an unknown quantity.

POSITIVELY OSTENTATIOUS.

Mr. Phunkstick (quite put out). "Talk about Agricultural Depression, indeed! Don't believe in it! Never saw Fences kept in such disgustingly good order in my life!"

Polite Police in Egypt.—The Anglo-Egyptian Police are to be converted into a civil force. Will Police Professors of Politeness be sent over from England to give lectures on civility?

Motto for any Authors writing Plays for the Garrick Theatre.—"Keep your Hare on!" 220

(A Story in Scenes.)

PART XIX.—UNEARNED INCREMENT.

Scene XXVII. (continued).—The Chinese Drawing Room.

Sir Rupert (to Tredwell). Well, what is it?

Tredwell (in an undertone). With reference to the party, Sir Rupert, as represents himself to have come down to see the 'orse, I——

Sir Rup. (aloud). You mean Mr. Spurrell? It's all right. Mr. Spurrell will see the horse to-morrow. (Tredwell disguises his utter bewilderment.) By the way, we expected a Mr.——What did you say the name was, my dear?... Undershell? To be sure, a Mr. Undershell, to have been here in time for dinner. Do you know why he has been unable to come before this?

Tred. (to himself). Do I know? Oh, Lor! (Aloud.) I—I believe he have arrived, Sir Rupert.

Sir Rup. So I understand from Mr. Spurrell. Is he here still?

Tred. He is, Sir Rupert. I—I considered it my dooty not to allow him to leave the house, not feeling——

Sir Rup. Quite right, Tredwell. I should have been most seriously annoyed if I had found that a guest we were all anxiously expecting had left the Court, owing to some fancied——Where is he now?

Tred. (faintly). In—in the Verney Chamber. Leastways——

Sir Rup. Ah. (He glances at Spurrell.) Then where——? But that can be arranged. Go up and explain to Mr. Undershell that we have only this moment heard of his arrival; say we understand that he has been obliged to come by a later train, and that we shall be delighted to see him, just as he is.

Spurrell (to himself). He was worth looking at just as he was, when I saw him!

Tred. Very good, Sir Rupert. (To himself, as he departs.) If I'm not precious careful over this job, it may cost me my situation!

Spurr. Sir Rupert, I've been thinking that, after what's occurred, it would probably be more satisfactory to all parties if I shifted my quarters, and—and took my meals in the Housekeeper's Room.

[Lady Maisie and Lady Rhoda utter inarticulate protests.

Sir Rup. My dear Sir, not on any account—couldn't hear of it! My wife, I'm sure, will say the same.

Lady Culverin (with an effort). I hope Mr. Spurrell will continue to be our guest precisely as before—that is, if he will forgive us for putting him into another room——

Spurr. (to himself). It's no use; I can't get rid of 'em; they stick to me like a lot of highly-bred burrs! (Aloud, in despair.) Your ladyship is very good, but——Well, the fact is, I've only just found out that a young lady I've long been deeply attached to is in this very house. She's a Miss Emma Phillipson—maid, so I understand, to Lady Maisie—and, without for one moment wishing to draw any comparisons, or to seem ungrateful for all the friendliness I've received, I really and truly would feel myself more comfortable in a circle where I could enjoy rather more of my Emma's society!

Sir Rup. (immensely relieved). Perfectly natural! and—hum—sorry as we are to lose you, Mr. Spurrell, we—ah—mustn't be inconsiderate enough to keep you here a moment longer. I daresay you will find the young lady in the Housekeeper's Room—anyone will tell you where it is.... Good-night to you, then: and, remember, we shall expect to see you in the field on Tuesday.

Lady Maisie. Good-night, Mr. Spurrell, and—and I'm so very glad—about Emma, you know. I hope you will both be very happy.

[She shakes hands warmly.

Lady Rhoda. So do I. And mind you don't forget about that liniment, you know.

Captain Thicknesse (to himself). Maisie don't care a hang! And I was ass enough to fancy——But there, that's all over now!

Scene XXVIII.—The Verney Chamber.

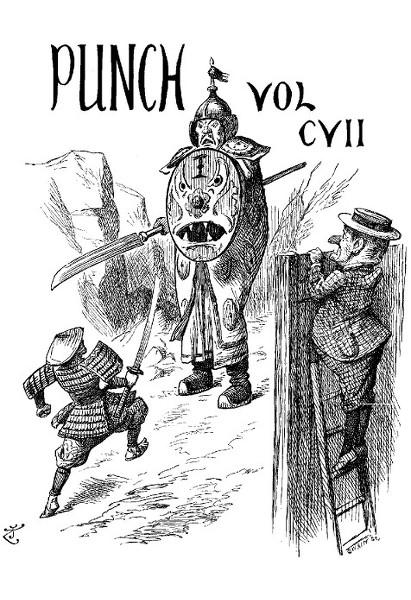

Undershell (in the dressing-room, to himself). I wonder how long I've been locked up here—it seems hours! I almost hope they've forgotten me altogether.... Someone has come in.... If it should be Sir Rupert!! Great Heavens, what a situation to be found in by one's host!... Perhaps it's only that fellow Spurrell; if so, there's a chance. (The door is unlocked by Tredwell, who has lighted the candles on the dressing-table.) It's the butler again. Well, I shall soon know the worst! (He steps out, blinking, with as much dignity as possible.) Perhaps you will kindly inform me why I have been subjected to this indignity?

Tred. (in perturbation). I think Mr. Undershell, Sir, in common fairness, you'll admit as you've mainly yourself to thank for any mistakes that have occurred; for which I 'asten to express my pussonal regret.

Und. So long as you realise that you have made a mistake, I am willing to overlook it, on condition that you help me to get away from this place without your master and mistress's knowledge.

Tred. It's too late, Sir. They know you're 'ere!

Und. They know! Then there's no time to be lost. I must leave this moment!

Tred. No, Sir, excuse me; but you can't hardly do that now. I was to say that Sir Rupert and the ladies would be glad to see you in the Droring Room himmediate.

Und. Man alive! do you imagine anything would induce me to meet them now, after the humiliations I have been compelled to suffer under this roof?

Tred. If you would prefer anything that has taken place in the Room, Sir, or in the stables to be 'ushed up——

Und. Prefer it! If it were only possible! But they know—they know! What's the use of talking like that?

Tred. (to himself). I know where I am now! (Aloud.) They know nothink up to the present, Mr. Undershell, nor yet I see no occasion why they should—leastwise from any of Us.

Und. But they know I'm here; how am I to account for all the time——?

Tred. Excuse me. Sir. I thought of that, and it occurred to me as it might be more agreeable to your feelings, Sir, if I conveyed an impression that you had only just arrived—'aving missed your train, Sir.

Und. (overjoyed). How am I to thank you? that was really most discreet of you—most considerate!

Tred. I am truly rejoiced to hear you say so, Sir. And I'll take care nothing leaks out. And if you'll be kind enough to follow me to the Droring Room, the ladies are waiting to see you.

Und. (to himself). I may actually meet Lady Maisie Mull after all! (Aloud, recollecting his condition.) But I can't go down like this. I'm in such a horrible mess!

Tred. I reelly don't perceive it, Sir; there's a little white on your coat-collar behind. Allow me—there, it's off now. (He gives him a hand-glass.) If you'd like to see for yourself.

Und. (to himself as he looks). A little pallor, that's all. I am more presentable than I could have hoped. (Aloud.) Have the kindness to take me to Lady Culverin at once.

Scene XXIX.—The Chinese Drawing Room.

A few minutes later.

Sir Rup. (to Undershell, after the introductions have been gone through). And so you missed the 4.55 and had to come on by the 7.30, which stops everywhere, eh?

Und. It—it certainly does stop at most stations.

Sir Rup. And how did you get on to Wyvern—been here long?

Und. N-not particularly long.

Sir Rup. Fact is, you see, we made a mistake. Very ridiculous, but we've been taking that young fellow, Mr. Spurrell, for you, all this time; so we never thought of inquiring whether you'd come or not. It was only just now he told us how he'd met you in the Verney Chamber, and the very handsome way, if you will allow me to say so, in which you had tried to efface yourself. 221

Und. (to himself). I didn't expect him to take that view of it! (Aloud.) I—I felt I had no alternative.

[Lady Maisie regards him with admiration.

Sir Rup. You did an uncommon fine thing, Sir, and I'm afraid you received treatment on your arrival which you had every right to resent.

Und. (to himself). I hoped he didn't know about the Housekeeper's Room! (Aloud.) Please say no more about it, Sir Rupert. I know now that you were entirely innocent of any——

Sir Rup. (horrified). Good Gad! you didn't suppose I had any hand in fixing up that booby trap, or whatever it was, did you? Young fellows will get bear-fighting and playing idiotic tricks on one another, and you seem to have been the victim—that's how it was. Have you had anything to eat since you came? If not——

Und. (hastily). Thank you, I—I have dined. (To himself.) So he doesn't know where, after all! I will spare him that.

Sir Rup. Got some food at Shuntingbridge, eh? Afraid they gave you a wretched dinner?

Und. Quite the reverse, I assure you. (To himself.) Considering that it came from his own table!

Lady Maisie (in an undertone, to Captain Thicknesse). Gerald, you remember what I said some time ago—about poetry and poets?

Capt. Thick. Perfectly. And I thought you were quite right.

Lady Maisie. I was quite wrong. I didn't know what I was talking about. I do now. Good night. (She crosses to Undershell.) Good night, Mr. Blair, I'm so very glad we have met—at last!

[She goes.

Und. (to himself, rapturously). She's not freckled; she's not even sandy. She's lovely! And, by some unhoped for good fortune, all this has only raised me in her eyes. I am more than compensated!

Capt. Thick. (to himself). I may just as well get back to Aldershot to-morrow—now. I'll go and prepare Lady C.'s mind, in case. It's hard luck; just when everything seemed goin' right! I'd give somethin' to have the other bard back, I know. It's no earthly use my tryin' to stand against this one!

Dear Mr. Punch,—Do not confuse me with a boa-constrictor story. Cursed be he that disturbs my bona fides; and the above is my real address.

True, the ancient Romans knew me as the Old Pretendress, but let that pass. What I want to know is this. Will nothing check the energy of the L. C. C.?—nothing allay their fever for expurgation? I am not a Promenader. I only ask to lie still. Nor a Living Picture either, and have not been for more than eighteen centuries. Talk of Roman noses! Why their eagle was a chicken compared with the London Carrion Crows! Such a power of scent!

It is Guy Fawkes day, and I hear talk of blowing up the Lords. But surely one must draw the line somewhere this side of an insidious exhumation of the Monarchy!

After all, if they do get at my bones, the real marrow of me has transmigrated into the New Woman. Sir, there were New Women in my day. We invented everything. I see the Daily Telegraph says they have found a pellet. That reminds me that after the death of my late husband, Prasutagus, King of the Iceni (not to be confused with the Plioceni of about the same period), I was subjected to the most revolting barbarity at the hands of the Veterans (their name was legionary), and I was obliged to invent a pellet-proof corset.

Then, again, we held all the commissions in the army. How does Tacitus report my famous speech to the Queen Consort's Own Regiment of Pioneers (new style)? "Vincendum illa acie vel cadendum esse. Id mulieri destinatum. Viverent viri et servirent." Let the men live on in slavery! What a prophetic utterance!

By the way, not many Emancipated Women of the present day could speak better Latin than that. Indeed, we took all the University degrees. I myself was an honorary felo de se.

Don't tell me that I am prehistoric, and that Tacitus was a forger of the fourteenth century. No testimony is sacred now-a-days, not even the most profane!

I conclude with a passage from Madame Sarah Gray, which I think comes in rather well.

Dear Mr. Punch, may you live for ever; or, failing that, may no rude spoiler mar your "animated bust." Excuse these disjointed remarks, but I am writing in a barrow.

Yours, in the spirit,

P.S.—I have thought of a proverb. New Women should be put into new tumuli.

Nothing could be better than the acting all round in the new three-act play at the Court. It is distinctly first-rate, and those who want a hearty laugh should proceed to the Court to enjoy it. And yet there is also serious relief, as there should be—light and shade. First there is Miss Lottie Venne, who shows us that she can mingle pathos with comedy, temper smiles with tears. She is as bright as sunshine in the comic scenes, and when she has to say good-bye to her newly-married daughter, she glides from peals of merriment into sobs of sorrow that are intensely touching because they are intensely natural. Then Mr. Hawtrey, in a part that fits him down to the ground (in the Stalls) and up to the ceiling (in the Gallery), is greatly amusing. And he, too, has his more mournful moments. People accustomed to seeing this accomplished actor in butterfly touch-and-go parts would scarcely credit him with the power of becoming pathetically unmanned. And yet so it is. Mr. Hawtrey, indignant at a false accusation emanating from his wife, commences a letter full of angry reproaches, addressed to her solicitors, and gradually forgets everything in his despairing appeal for the love he craves but which he fears he has lost. Nothing better than this has been seen for a long time in a London theatre. Then Mr. Gilbert Hare (inheritor of his father's cleverness) causes roars of laughter by his comical sketch of a man with a cold. But here, again, the mirth is tempered with sympathy. The echo of the "ha, ha, ha," in spite of its inappropriateness, is "Poor fellow!" Mr. Thorne, too, is good, and so is Mr. Righton, and so is everyone concerned.

["Canon Furse said he believed no man's education was complete who did not attend public meetings."—Daily News.]

Home for Advertisers.—"Puffin Island." Of course this is only for those who find themselves in "many straits." 222

DRAWING-ROOM INANITIES.

He. "I live in Hill Street. Where do you live?"

She. "I live in Hill Street, too."

He (greatly delighted to find they have something in common). "Really!" (After a moment's hesitation.) "Any particular Number?"

What His Lordship must have Said.—A juryman in a recent case objected to a private soldier, who is a public servant, being described as "one of the lower classes." The Lord Chief Justice explained that the witness had said "rough classes," not "lower," adding his dictum that "patent leather boots do not make a man first class." This remark was à propos de bottes; and what the Chief meant to say was evidently that "patent leather boots were not to be considered as a patent of nobility." When Frank Lockwood, Q.C., M.P., Attorney-General, heard of it, he wept as for another good chance gone for ever.

Caught Punning.—In some of the theatrical items for the week we see it announced that a certain playwright is at work on a comic opera which has for its subject Manon Lescaut. "If it is to be a travestie," observed "W. A.," the World's Archer, who makes a shot at a pun whenever the chance is given him, "then its title should of course be 'Manon Bur-Lescaut.'"

"Reform in Conveyancing."—Certainly, a reform much needed. Let us have some new Hansoms which are not "bone-shakers" and whose windows will not act as so many guillotines. Some improved growlers (they have been a bit better recently), drawn by less dilapidated horses, would be a welcome addition. 223

224

225

(A Colour-Study in Green Carnations.)

They were sitting close together in their characteristic attitudes; the knees slightly limp, and the arms hanging loosely by their sides; Lord Raggie Tattersall in the peculiar kind of portable chair he most affected; Fustian Flitters in a luxurious sort of handbarrow. The lemon-tinted November light of a back street in a London slum floated lovingly on their collapsed forms, and on the great mass of weary cabbage-stalks that lay dreaming themselves daintily to death in the gutter at their feet.

They were both dressed very much alike, in loosely-fitting, fantastically patched coats. Lord Raggie was wearing a straw hat, with the crown reticently suggested rather than expressed, which suited his complexion very well, emphasising, as it did, the white weariness of his smooth face, with the bright spot of red that had appeared on each cheek, and the vacant fretfulness of his hollow eyes; he held his head slightly on one side, and seemed very tired. Fustian Flitters had adopted the regulation chimney-pot hat, beautiful with the iridescent sheen of decay; he was taller, bulgier, and bulkier than his friend, and allowed his heavy chin to droop languidly forward. Both wore white cotton gloves, broken boots, and rather small magenta cauliflowers in their button-holes.

"My dear Raggie," said Mr. Flitters, in a gently elaborate voice, and with a gracious wave of his plump straw-distended white fingers towards his companion's chair; "you are looking very well this afternoon. You would be perfectly charming in a red wig and a cocked-hat, and a checked ulster with purple and green shadows in the folds. You would wear it beautifully, floating negligently over your shoulders. But you are wonderfully complete as you are!"

"That is so true!" acquiesced Raggie, with perfect complacency. "I am very beautiful. And you, Fustian, you are so energetically inert. Are you going to blow up to-night? You are so brilliant when you blow up."

"I have not decided either way. I never do. It will depend upon how I feel in the bonfire. I let it come if it will. The true impromptu is invariably premeditated."

"Isn't that rather self-contradictory?" said Raggie, with his pretty quick smile.

"Of course it is. Does not consistency solely consist in contradicting oneself? But I suppose I am a trifle décousu."

"You are. Indeed, we are both what those absurd clothes-dealing Philistines would call 'threadbare'—you and I."

"I hope so, most sincerely. There is something so hopelessly middle-class about wearing perfectly new clothes. It always reminds me of that ridiculous Nature, who will persist in putting all her poor little trees into brand-new suits of hideous non-arsenical green every spring. As if withered leaves, or even nudity itself, would not really be infinitely more decent! I detest a coat that is what the world calls a 'fit!'"

"Clothes that fit," observed Lord Raggie, gravely, "are the natural penalty for possessing that dreadful deformity, a good figure. Only exploded mediocrities like Tupper and Bunn and Shakspeare ought to have figures."

"Had Shakspeare a figure? I thought it was only a bust."

"We shall have our little bust by and by, I suppose," said Raggie, pensively. "I wonder when. I feel in the mood to sally forth and paint the night with strange scarlet, slashed with silver and gold, while our young votaries—beautiful pink boys in paper hats—let off marvellous pale epigrammatic crackers and purple paradoxical squibs in our honour."

"See, Raggie, here come our youthful disciples! Do they not look deliciously innocent and enthusiastic? I wish, though, we could contrive to imbue them with something of our own lovely limpness—they are so atrociously lively and active."

"That will come, Fustian," said Lord Raggie, indulgently. "We must give them time. Already they have copied our distinctive costume, caught our very features and colouring. Some day, Fustian, some day they will adopt our mystic emblem—the symbol that is such a true symbol in possessing no meaning whatever—the Magenta Cauliflower! And then—and then——."

"——It will be time for Us to drop it," continued Mr. Fustian Flitters, with his peculiar smile of inscrutable obviousness.

"Beautiful rose-coloured children!" murmured Lord Raggie, dreamily; "how sad to think that they will all grow up and degenerate into pork-butchers, and generals, and bishops, and absurdly futile persons of that sort! But listen; it is so sweet of them—they are going to sing an exquisite little catch I composed expressly for them, a sort of mellifluously raucous chant with no tune in particular. That is where it is so wonderful. True melody is always quite tuneless!"

One by one the shrill, passionate young voices chimed in, until the very lamp-posts throbbed and rang with the words, and they seemed to wander away, away among the sleeping pageant of the chimney-pots, away to the burnished golden globes of the struggling pawnbroker.

Lord Raggie, with his head bent, listened with a smile parting the scarlet thread of his lips, a smile in his pretty hollow eyes. "I wonder why people should be exhorted to remember such a prosaic and commonplace crime as that," he meditated aloud: "a crime, too, that had not even the vulgar merit of being a success!"

"Only failures ever do succeed, really," said Fustian, leaning largely over his barrow. "How deliciously they are joggling us! Don't you like having your innermost shavings stimulated, Raggie?"

"There is only one stimulating thing in the world," was the languid answer; "and that is a soporific. But see, Fustian, here comes one of those unconsciously absurd persons they call policemen. How stiffly he holds himself. Why is there something so irresistibly ludicrous about every creature that possesses a spine? Perhaps because to be vertebrate is to be normal, and the normal is necessarily such a hideous monstrosity. I love what are called warped distorted figures. The only real Adonis nowadays is a Guy." And the shrill voices of the young choristers, detaching themselves one by one from the melodic fabric in which they were enmeshed, grew fainter and fainter still—until they slipped at last into silence. "Fustian, did you notice? Our rose-white adherents have abandoned us. They have run away—'done a guy,' as vulgarians express it."

"They have done two," said Mr. Flitters correctively; "which only proves the absolute sincerity of their devotion. Is not the whole art of fidelity comprised in knowing exactly when to betray?"

"How original you are to-day, Fustian! But what is this crude blue copper going to do with you and me? Can we be going to become notorious—really notorious—at last?"

"I devoutly trust not. Notoriety is now merely a synonym for respectable obscurity. But he certainly appears to be engaged in what a serious humourist would call 'running us in.'"

"How pedantic of him! Then shan't we be allowed to explode at all this evening?"

"It seems not. They think we are dangerous. How can one tell? Perhaps we are. Give me a light, Raggie, and I will be brilliant for you alone. Come, the young Shoeblack bends to his brush, and the pale-faced Coster watches him in his pearly kicksies; the shadows on the mussels in the fish-stall are violet, and the vendor of halfpenny ices is washing the spaces of his tumblers with primrose and with crimson. Let me be brilliant, dear boy, or I feel that I shall burst for sheer vacuity, and pass away, as so many of us have passed, with all my combustibles still in me!"

And with gentle resignation, as martyrs whose apotheosis is merely postponed, Lord Raggie and Fustian Flitters allowed themselves to be slowly moved on by the rude hand of an unsympathetic Peeler. 226

227

(By an Affable Philosopher and Courteous Friend.)

The Choice of a Private Secretary.

Having explained the mode of entering the service of the Crown by becoming the Secretary of the Public Squander Department, I now proceed to consider the best manner in which you should comport yourself in that position. The moment it is known that you have accepted the appointment you will receive a deluge of letters recommending various aspiring young gentlemen for the post of Private Secretary. Of course the notes must be civilly answered, but on no account pledge yourself to any one of the writers. And here I may give what may be termed the golden rule of the service, "always be polite to the individual in particular, and contemptuous to the public in general." The tradition of many generations of officials has been to regard outsiders as enemies. There may be small jealousies in a Government Department, but every man in the place will stand shoulder to shoulder with his fellow to repel the attacks of non-civilians. And the word "attack" has many meanings. Practically, everything is an attack. If an outsider asks a question, the query is an attack. If an outsider complains, the grievance is an attack. If an outsider begs a favour, the petition is an attack. If you bear this well in mind, you cannot go wrong. Adopt it as your creed, and you may be sure that you will became immediately an ideal head of a Government Department.

Say that you have accepted your appointment, and are prepared to take up at once the duties appertaining to your new position. No doubt during your "attacks" upon the Milestones you will have come across several of the officials of the Public Squander Department. So when you arrive in the hall of your new bureau you will be recognised at once by most of the messengers. You will be conducted with deference to your new quarters. You will find them very comfortable. Any number of easy-chairs. Large writing-desk. Several handsome tables. Rich carpet, rugs to match, and a coal-scuttle with the departmental cypher. On the walls, maps and some armour. The latter, no doubt, has come from the Tower, or Holyrood, or Dublin Castle. Most probably one of your predecessors has given an official dinner in your room, and the armour is the result of the importunity of his Private Secretary.

"I say, Tenterfore," your predecessor has observed, "don't you think these walls are a bit bare? Don't you think you could get them done up a bit?"

"Certainly, Sir," Tenterfore has replied, and the result of his energy has been the trophies you see around you. Tenterfore has applied to the people at the Tower, or Holyrood, or Dublin Castle, and got up quite a collection of quaint old arms. They have been duly received by the Public Squander Department, and retained. It is a rule of the bureau that anything that has been once accepted shall be kept for ever. That is to say, if it can be clearly proved that the things retained can be useful somewhere else. You look round with satisfaction, and then greet with effusion the chief clerk. He has been waiting to receive you. As you do not know the ropes, it is advisable to be civil to every one. Later on, when you have a talented assistant to prompt you, you can allow your cordiality to cool. However, at this moment it is better to be extremely polite to all the world, and (if you know her) his wife. The chief clerk is delighted to exchange expressions of mutual respect and common good-will. He will put in something neat about the Milestones as a concession to your labours in that direction.

"My dear Sir," you will reply with a smile, "don't bother yourself about them. I can keep them quite safe. We have nothing to fear from them."

The face of the chief clerk will beam. He will see that you are one of them. Milestones for the future are to be defended, not attacked. He will accept you as an illustrious bureaucratic recruit. He will see that you are ready to stand shoulder to shoulder in defence of the office. Could anything be better?

Then for about the thirtieth time you will be asked if you have selected a private secretary, and the chief clerk will suggest his own particular nominee. With much cordiality you will receive the proposal, but keep the matter open. You must remember that upon the appointment your future success depends. Moreover, it is a nice little piece of patronage which you may as well retain for yourself.

When you have selected your private secretary it will be time to get into harness, and of this operation I hope to treat on some future occasion.

HOW OPINION IS FORMED.

He. "Have you read that beastly Book The Mauve Peony, by Lady Middlesex?"

She. "Yes. I rather liked it."

He. "So did I."

"No Fees!"—The new seats in the Drury Lane pit "by an ingenious arrangement," says Mr. Clement Scott, in the Daily Telegraph, "'tip up' of their own accord the instant they are vacated." Then, evidently, the system of "fees to attendants" is not abolished at T.R. Drury Lane. In theatres where it is abolished no "tipping up" could possibly be permitted. 228

Gleams of Memory; with Some Reflections, is the happy title of Mr. James Payn's last book, published by Smith and Elder. The wit of the title flashes through every page of the single volume. Within its modest limits of space will be found not only some of the best stories of the day, but stories the best told. Not a superfluous word spoils the gems, which have been ruthlessly taken out of their setting and spread widecast through the circulation of many newspapers reviewing the work. My Baronite, fortunately, has not space at his disposal to join in this act of flat, though seductive, burglary. He advises everyone to go to the book itself. The reader will find himself enjoying the rare privilege of intimacy with a cultured mind, and a heart so kindly that temptation to say smart things at the expense of others, which underlies the possession of overflowing humour, is resisted, apparently without effort. Like the German Emperor or Mr. Justin Mccarthy, Mr. Payn probably "could be very nasty if he liked." He doesn't like, and is therefore himself liked all the better.

That little tale entitled The Black Patch, by Gertrude Clay Ker-Seymer, introduces to the public a rather novel character in the person of a Miss Clara Beauchamp an amateur female detective, to whom Sherlock Holmes, when he chooses to "come out of his ambush," (for no one believes he fell over that precipice and was killed about a year ago,) ought at once to propose. It would be an excellent firm. Clara would make our Holmes happy, and a certain advertising medicine provider bearing the same name as the heroine of this sporting story would have another big chance of increasing his "hoardings." The Baron, skilled as he is in plots, owns to having been now and again puzzled over this one which clever Clara the Clearer soon makes apparent to everybody. The story is a working out of the description of twins, how "each is so like both that you can't tell t'other from which." But mind you, not ordinary biped twins—oh dear no—they are.... No ... the Baron respects a lady's secret, and recommends the inquisitive to get the book and penetrate the mystery.

To all those who like a mystery, and who gratefully remember Florence Warden's House on the Marsh, let the Baron recommend A Perfect Fool, by the same authoress. Dickensian students will be struck by the fact of a "Mr. Dick" being kept on the premises. He is a caged Dickie, poor chap; but, like his ancestor the original Mr. Dick, he sets everybody right at last. The Baron dare not say more, lest he should let the Dickie out of the cage. The only disappointment, to old-fashioned novel-readers, at least, who love justice to be done, and the villain to receive worse than he has given, is in the moral of the tale; yet in these decadent Yellow Asterical and Green Carnational days it is as good as can be wished. Florence Warden is neither priggish nor Church-Wardenish; and so, when the scoundrel——But here, again, the Baron must put his finger to his lips, and ask you to read the story; when, and not till then, he may imagine whether you do not agree with him, "Mystère!"

Curiosity has ever been a weakness of human nature, and that seems to be the only reason why so many make themselves uncomfortable by taking journeys to the Pole. Imitating Nansen, Gordon Stables, M.D., R.N., sends his hero To Greenland and the Pole, which he reaches after much "skilöbning" (the book must be read to grasp its meaning), and receiving a chilly but polite welcome, with the arrogance of an Englishman breaks the cold silence by singing the "National Anthem," when of course the Pole is thawed at once!

Writes a Baronitess Junior, "Those little boys and girls who delight in fairy lore will find a charming story of magical adventures in Maurice; or, the Red Jar, by the Countess of Jersey, or more appropriately Countess of Jarsey. It is fantastically illustrated by Rosie M. M. Pitman, and published by Macmillan & Co., and shows how unpleasant a jar can be in a family. And yet has not the poet finely said, 'A thing of beauty is a Jar for ever!'"

The Baron is anxiously expecting the appearance from The Leadenhall Press of Mr. Tuer's Chap-book. Of course, all "the Chappies" from "Chap 1" to "Last Chap" are on the look out for it. The Baron fancies it will be a perfect fac-simile, and if not perfect, the merciful critic who is merciful to his author will say with the poet Pope

"Tu er is human,"

which is a most pope-ular quotation; while as to the latter half of the line "to forgive, divine"—that, in a measure, is one of the unstrained prerogatives of the

(Suggested by the recent Debate (Ladies only) at the Pioneers Club on the Shortcomings of the Male Sex.)

Nova mulier vociferatur more Whitmanico.

This sort of thing goes on for about twenty more verses, for which readers are kindly referred to the original in Leaves of Grass. It really applies without any further adaptation.

On Lord Mayor's Day.

Footnotes

1 Iliad, B. V., 478.

Transcriber's Note:

Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation are as in the original.