CONTENTS

More than He Bargained for—The War Fever and How it Affected the Boys—A Disbanded Cavalryman—Going to School in Uniform—Cousin Tom from Shiloh?—Running Away to Enlist—The Draft—In the Griswold Cavalry—Habeas Corf used.

N the local columns of the Troy (N. Y.) Daily Times of September 1, 1863, the following news:

“A few days ago one Stanton P. Allen of Berlin, enlisted in Capt. Boutelle's company of the twenty-first (Griswold) cavalry. We are not informed whether it was Stanton's bearing the same name as the Secretary of War, or his mature cast of countenance that caused him to be accepted; for he was regarded as nineteen years of age, while, in reality but fourteen summers had passed over his youthful, but ambitious brow. Stanton received a portion of his bounty and invested himself in one of those 'neat, but not gaudy' yellow and blue suits that constitute the uniform of the Griswold boys. A few days intervened. Stanton's 'parients,' on the vine-clad hills of Berlin, heard that their darling boy had 'gone for a sojer.' Their emotions were indescribable. 'So young and yet so valiant,' thought his female relatives. 'How can I get him out?' was the more practical query of his papa. The ways the ways and means were soon discovered. A writ of habeas corpus was procured from Judge Robertson, and as the proof was clear that Stanton was only fourteen years old, he was duly discharged from the service of the United States. But the end was not yet. A warrant was issued for the recruit, charging him with obtaining bounty and uniform under false pretenses, and a release from the military service proved only a transfer to the civil power. Stanton found that he had made a poor exchange of 'situations,' and last evening gave bail before Judge Robertson in the sum of five hundred dollars.”

In order that the correctness of history may not be questioned, the subject of the above deems it expedient to place on record an outline of the circumstances leading up to the incident related by the Times.

At the breaking out of the war my father resided in Berlin, N. Y., on the Brimmer farm, three miles or so from the village. I was twelve years old, but larger than many lads of sixteen. I was attacked by the war fever as soon as the news that Fort Sumter had been fired on reached the Brimmer farm. Nathaniel Bass worked for my father that year. The war fever got hold of Nat after haying was over, and one night along in the latter part of August, he said to me:

“I'm going to war.”

“You don't mean it, Nat?”

“Yes, I do. The fall's work won't last long, and they say they're paying thirteen dollars a month and found for soldiers. That's better'n doing chores for your board.”

“If you do go I'll run away and enlist.”

“No; you're too young to go to war. You must wait till you're an able-bodied man-that's what the bills call for.”

“O, dear! I'm afraid you'll whip all the rebels before I can get there.”

I cried myself to sleep that night.

How I envied Nat when he came home on a three days' furlough clad in a full suit of cavalry uniform! He enlisted September 20, 1861, in the Second New York cavalry. The regiment was known as the Northern Black-horse cavalry. Nat allowed me to try on his jacket, and I strutted about in it for an hour or so. I felt that even in wearing it for a short time I was doing something toward whipping the Southerners. But Bass's furlough came to an end, and he returned to his regiment.

Nat came back in time to help us plant in the spring of 1862. The regiment went as far as Camp Stoneman, near Washington, where it remained in winter quarters. It was not accepted by the United States Government, and was never mounted. The reason given was that the Government had more cavalry than it could handle, and the Northern Black-horse cavalry was disbanded. The regiment was raised by Colonel Andrew J. Morrison, who subsequently served with distinction at the head of a brigade.

Nat came home “chock-full” of war stories. He was just as much a hero in my estimation as he would have been if the rebels had shot him all to pieces. I never tired of listening to his yarns about the experiences of the regiment at Camp Stoneman. He had not seen a rebel, dead or alive, but that was not his fault. Nat was something of a singer, and he had a song describing the adventures of his regiment. The soldiers were referred to as “rats.” I recall one verse and the chorus:

“The rats they were mustered,

And then they were paid;

'And now,' says Col. Morrison,

'We'll have a dress parade.'

Lallv boo!

Lally boo, oo, oo,

Lally bang, bang, bang,

Lally boo, oo, oo,

Lally bang!”

I would join in the chorus, and although I did not understand the sentiment—if there was any in the song—I was ready to adopt it as a national hymn.

I was the proudest boy in the Brimmer district at the opening of school the next winter. I fairly “paralyzed” the teacher, George Powell, and all the scholars, when I marched in wearing Nat's cavalry jacket and forage cap. He had made me a present of them. I was the lion of the day. The jacket fitted me like a sentry-box, but the girls voted the rig “perfectly lovely.” Half a dozen big boys threatened to punch my eyes out if I did not “leave that ugly old jacket at home.” I enjoyed the notoriety, and continued to wear the jacket. But one day Jim Duffy, a boy who worked for Tom Jones, came into the school with an artillery jacket on. It was of the same pattern as the jacket I wore, but had red trimmings in place of yellow. The girls decided that Jim's jacket was the prettier. I made up my mind to challenge Jim at the afternoon recess, but my anger moderated as I heard one of the small girls remark:

“But Jim ain't got no sojer cap, so he ain't no real sojer—he's only a make-b'lief.”

“Sure enough!” chorused the girls.

Then I expected Duffy to challenge me, but he did not, and there was no fight.

That same winter Thomas Torrey of Williamstown came to our house visiting. Tom was one of the first to respond to the call for volunteers to put down the rebellion. He was in the Western army, and fought under Grant at Shiloh. He received a wound in the second day's fight, May 7, 1862, that crippled him for life. He had his right arm extended to ram home a cartridge, when a rebel bullet struck him in the wrist. The ball shattered the bone of the forearm and sped on into the shoulder, which it disabled. Tom's good right arm was useless forever after.

Tom was a better singer than Bass, and as we claimed him as our cousin, it seemed as if our family had already shed blood to put down the rebellion.

While the wounded soldier remained at our house and told war stories and sang the patriotic songs of the day, my enthusiasm was kept at one hundred and twenty degrees in the shade. I made up my mind that I would go to war or “bust a blood vessel.” I assisted in dressing Tom's shattered arm once or twice, but even that did not quench the patriotic fire that had been kindled in my breast by Bass's war stories and fanned almost into a conflagration by Tom's recital of his experiences in actual combat.

I discarded Nat's “Lally boo” and transferred my allegiance to a stirring song sung by Tom:

“At Pittsburg Landing

Our troops fought very hard;

They killed old Johnston

And conquered Beauregard.”

Chorus: “Hoist up the flag;

Long may it wave

Over the Union boys,

So noble and so brave.”

I laid awake nights and studied up plans to go to Pittsburg Landing and run a bayonet through the rebel who shot “Cousin Tom.”

The summer of 1862 was a very trying time. Charley Taylor of Berlin, opened a recruiting office in the village and enlisted men for Company B, One hundred and twenty-fifth New York volunteers. I wanted to go, but when I suggested it to my father he remarked:

“They don't take boys who can't hoe a man's row. You'll have to wait five or six years.”

When the Berlin boys came home on furlough from Troy, to show themselves in their new uniforms and bid their friends good-by, it seemed to me that my chances of reaching the front in time to help put down the rebellion, were slim indeed. I reasoned that if Nat Bass could have driven the rebels into Richmond alone—as he said he could have done if he had been given an opportunity—the war would be brought to a speedy close when Company B was turned loose upon the Confederates in Virginia. It seemed that nearly everybody was going in Company B except Bass and I. I urged Nat to go, but he said it would be considered “small potatoes for a man who had served in the cavalry to re-enlist in the infantry.” If I had not overlooked the fact that Nat had never straddled a horse during his six months' service in Col. Morrison's regiment, I might have questioned the consistency of Bass's position.

The One hundred and twenty-fifth left Troy Saturday, August 30, 1862, and on the same day the second battle of Bull Run was fought, resulting in the retreat of the Union Army into the fortifications around Washington.

“I told you so,” said Bass, when the news of the battle reached Berlin. “The boys in Company B will have their hands full. They will reach the front in time to take part in this fall's campaign. I shall wait till next summer, and then if there's a call for another cavalry regiment to fight the rebels, I'll go down and help whip 'em some more.”

When the news of Grant's glorious capture of Vicksburg, and Meade's splendid victory at Gettysburg, was received in Berlin, I made up my mind that the crisis had arrived. I said to Bass:

“Nat, our time's come.”

“How so?”

“We've waited a year, and they've called for another regiment of cavalry.”

“Then I believe I'll go.”

“So'll I.”

“Where's the regiment being raised?”

“In Troy.”

“Will your father let you go?”

“Of course not—don't say a word to him. But I tell you, Nat, I'm going. The Union armies are knocking the life out of the rebels east and west, and it's now or never. I can't stand it any longer. I'm going to war.”

I was only a boy—born February 20, 1849—but thanks to an iron constitution, splendid health and a vigorous training in farm work, I had developed into a lad who would pass muster for nineteen almost anywhere.

Bass got away from me. My father drove to Troy with Nat, who enlisted August 7, in Company E, of the Griswold cavalry. The regiment was taken to the front and into active service by the late General William B. Tibbits of Troy.

About the first of August a circus pitched its tents in Berlin. Everybody went to the show. While the acrobats were vaulting about in the ring, a lad in a cavalry uniform entered the tent and took a seat not far from where I was sitting. The circus was a tame affair to me after that. A live elephant was nowhere when a boy in blue was around.

“Who's that soldier?” I asked my best girl.

“That's Henry Tracy; I wish he'd look this way. He's too sweet for anything.”

“Where's he from?”

“Off the mountain, from the Dutch settlement near the Dyken pond. Isn't he lovely! What a nobby suit!”

When the circus was out, I managed to secure an interview with the “bold sojer boy,” who informed me that he was in the same camp with Bass at Troy.

“How old are you?” I asked Tracy.

“I'm just eighteen,” he answered, with a wink that gave me to understand that I was not to accept the statement as a positive fact.

“Do you think they'd take me?”

“Certainly; you're more'n eighteen.”

“When are you going back?”

“Shall start to-night. Think you'll go along?”

“Yes; if you really think they'll take me.”

“I'm sure they will; you just let me manage the thing for you.”

“All right; I'm with you.”

I went with Tracy that night—after he had seen his girl home. As we climbed the steep mountain, I expected every minute to hear the footsteps of a brigade of relatives in pursuit. We reached the Tracy domicile about midnight, and went to bed. I could not sleep. The frogs in the pond near the house kept up a loud chorus, led by a bull-frog with a deep bass voice. I had heard the frogs on other occasions when fishing in the mountain lakes, and the boys agreed that the burden of the frog chorus was:

You'd better go round!

You'd better go round!

We'll bite your bait off!

We'll bite your bait off!

Somehow the chorus seemed that night to have been changed. As I lay there and listened for the sound of my father's wagon, the frogs sang after this fashion:

You'd better go home!

You'd better go home!

They'll shoot your head off!

They'll shoot your head off!

And, oh! how that old bull-frog with the bass voice came in on the chorus:

“They'll shoot your head off!”

We got up at daylight, and walked over to the plank road and waited for the stage from Berlin to come along, en route to Troy. When the vehicle came in sight, I hid in the bushes until Tracy could reconnoiter and ascertain if iny father was on board. He gave a signal that the coast was clear, and we took passage for the city.

“You're Alex Allen's boy?” the driver—Frank Maxon—said, as we took seats in the stage.

“What about it?”

“I heard 'em say at the post-office this morning that you'd run away.”

“False report,” said Tracy; “he's just going to Troy to bid me good-by.”

“Well, he must be struck on you, as they say he never set eyes on you till yesterday.”

The stage rattled into Troy about half-past ten o'clock. There was considerable excitement in the city over the draft. Soldiers were camped in the court-house yard and elsewhere. They were Michigan regiments, I think. There was a section of artillery in the yard of the hotel above the tunnel. I could not understand how it was that the Government was obliged to resort to a draft to secure soldiers. To me it seemed that an ablebodied man who would not volunteer to put down the rebellion, was pretty “small potatoes.”

But I was only a boy. Older persons did not look at it in the same light as I did. By the way, the draft euchred our family out of three hundred dollars. When I enlisted in the First Massachusetts, after the failure of my plan to reach Dixie in the Griswold cavalry, I was paid three hundred dollars bounty. I sent it home to my father. The draft “scooped him in,” and the Government got the three hundred dollars back, that being the sum the drafted men were called on to pay to secure exemption.

Tracy escorted me to Washington Square, where there were several tents in which recruiting officers were enlisting men for the Griswold cavalry. A bounty of two dollars was paid to each person bringing in a recruit. Tracy sold me to a sergeant named Cole for two dollars, but he divided the money with me on the way to camp. As we entered the tent where Sergeant Cole was sitting, Tracy said:

“This young man wants to enlist, Sergeant.”

“All right, my boy; how old are you—nineteen, I suppose?”

“Of course he's nineteen,” said Tracy.

I did not contradict what my soldier friend had said, and the sergeant made out my enlistment papers, Tracy making all the responses for me as to age. After I had been “sworn in” for three years, or during the war, I was paid ten dollars bounty. Then we went up to the barracks, and I was turned over to the first sergeant of Captain George V. Boutelle's company. I drew my uniform that night. The trousers had to be cut off top and bottom. The jacket was large enough for an overcoat. The army shirt scratched my back—but what is the use of reviving dead issues!

One day orders came for Capt. Boutelle's company to “fall in for muster.” The line was formed down near the gate. I was in the rear rank on the left. The mustering officer stood in front of the company with the roll in his hand. Just at this time, my father with a deputy sheriff arrived with the habeas corpus, which was served on Capt. Boutelle, and I was ordered to “fall out.”

Then we went to the city, to the office of Honorable Gilbert Robertson, Jr., provost judge, and after due inquiry had been made as to “the cause of detention by the said Capt. Boutelle of the said Stanton P. Allen,” the latter “said” was declared to be discharged from Uncle Sam's service. My father refunded the ten dollars bounty, and offered to return the uniform, but Capt. Boutelle refused to accept the clothes, charging that I had obtained property from the Government under false pretenses. Under that charge I was held in five hundred dollars bail, as stated in the Times, but the court remarked to my father that “that'll be the end of it, probably, as the captain will be ordered to the front, and there will be no one here to prosecute the case.”

As we were leaving Judge Robertson's office, a policeman arrested me. He marched me toward the jail. Pointing to the roof of the prison he said:

“My son, I'm sorry for you.”

“What are you going to do with me?” I asked.

“Put you in jail.”

“What for?”

“Defrauding the Government. But I'm sorry to see you go to jail. They may keep you there for life. They'll keep you there till the war is over, any way, for people are so busy with the war that they can't stop to try cases of this kind. You are charged with getting into the army without your father's consent. Maybe they won't hang you, but it'll go hard with you, sure. I don't want to see you die in prison. If I thought you'd go home and not run away again, I'd let you escape.” That was enough. I double-quicked it up the street and hid in the hotel barn where my father's team was until he came along. I was ready to go home with him. I did not know at that time that the arrest, after I had been bailed, was a put-up job. It was intended to frighten me. And it worked to a charm. It was a regular Bull Run affair.

The War Fever Again—Going to a Shooting Match—Over the Mountains to Enlist—A Question of Age—Sent to Camp Meigs—The Recruit and the Corporal—The Trooper's Outfit—A Cartload of Military Traps—Paraded for Inspection—An Officer who Had Been through the Mill.

RETURNED to Berlin very much discouraged. There had not been anything pleasant about our camp life in Troy—the food was poorly cooked, the camp discipline was on the go-as-you-please order at first, and sleeping on a hard bunk was not calculated to inspire patriotism in lads who had always enjoyed the luxury of a feather bed. Yet the thought that I was a Union soldier, and a Griswold cavalryman to boot, had acted as an offset to the hardships of camp life, and after my return home the “war fever” set in again. The relapse was more difficult to prescribe for than the first attack. The desire to reach the front was stimulated by the taunts of the wiseacres about the village who would bear down on me whenever I chanced to be in their presence, as follows:

“Nice soldier, you are!”

“How do the rebels look?”

“Sent for your father to come and get you, they say.”

“Did they offer you a commission as jigadier brindle?”

“When do you start again?”

Quite a number of the boys about the village and from the back hollows interviewed me now and then in respect of my army experience. I was a veteran in their estimation. After several conferences, a company of “minute-men” was organized. We started with three members—Irving Waterman, Giles Taylor and myself. I was elected captain, Waterman first lieutenant and Taylor second lieutenant. We could not get any of the other boys to join as privates. They all wanted to be officers, so we secured no recruits. It was decided that we would run away and enlist at the first opportunity. Taylor was considerable of a “boy” as compared with Waterman and myself, as he was married and a legal voter. Waterman was nearly two years my senior, but as I had “been to war” they insisted that I should take the lead and they would follow.

We finally fixed upon Thanksgiving Day in November, 1863, the time to start for Dixie. Waterman had scouted over around Williamstown, and he came back with the report that two Williams College students were raising a company of cavalry. Thanksgiving morning I informed my mother that I was going to a shooting match. It proved to be more of a shooting match than I expected. The minute-men met at a place that had been selected, and started for Dixie.

At the Mansion House, Williamstown, we introduced ourselves to Lieutenant Edward Payson Hopkins, son of a Williams College professor. The lieutenant was helping his cousin, Amos L. Hopkins, who had been commissioned lieutenant and who expected to be a captain, to raise a company.

“As soon as he secures his quota, I shall enlist for myself,” said the lieutenant, who added, that we could put our names down on his roll and he would go with us to North Adams, at which place we could take cars for Pittsfield, where Captain Hopkins's recruiting office was located. We rode to North Adams in a wagon owned by Professor Hopkins and which was pressed into service for the occasion by the professor's soldier son. The lieutenant handled the lines and the whip, he and I occupying the seat, and Taylor and Waterman sat on a board placed across the wagon behind.

At North Adams we were taken into an office where we were examined by the town war committee.

One of the committee was Quinn Robinson, a prominent citizen. I was called before the committee first, and having been through the mill before, I managed to satisfy the committee that I was qualified to wear a cavalry uniform and draw full rations. I remember that in canvassing the question of age—or rather what we should say on that subject—we had agreed to state that we were twenty-one. I was not fifteen until the next February. The examiners did not question my age.

“We won't say twenty-one years,” said Waterman, “and so we won't lie about it.”

After I had been under fire for some time I was told to step aside, and Waterman was brought before the examiners.

“He looks too young,” said Mr. Robinson to Lieutenant Hopkins.

“Well, question him, suggested the lieutenant.

“How old are you? inquired the committee man.

“Twenty-one, sir,” replied Waterman.

“When were you twenty-one?”

“Last week.”

“I think you're stretching it a little.”

“No, sir; I'm older than Allen, who has just been taken in.”

“I guess not; you may go out in the other room by the stove and think it over.”

Our married man Taylor was next called in.

“We can't take you,” said Robinson.

“What's matter?” exclaimed Giles.

“You're not old enough.”

“How old've I got to be?”

“Twenty-one, unless you get the consent of your parents.”

“Taylor's a married man,” I whispered to Lieutenant Hopkins.

“Don't tell that, or he'll be asked to get the consent of his wife,” said the lieutenant, also in a whisper.

The committee contended that Taylor would not fill the bill. Waterman was recalled, and Mr. Robinson said:

“Well, you've had time to think it over. Now how old are you?”

“Twenty-one, last week.”

“I can't hardly swallow that.”

“See here, Mr. Quinn” (I had not heard the committee man's other name then), I interrupted. “We three have come together to enlist. You have said that I can go. Taylor may be a trifle under age, but what of it? If you don't take the three of us none of us will go.”

There was more talk of the same kind, but finally the war committee decided to send us on to Pittsfield and let the recruiting authorities of that place settle the question of Taylor and Waterman's eligibility.

There was no trouble at Pittsfield, and we were forwarded to Boston in company with several other recruits. The rendezvous was at Camp Meigs in Readville, ten miles or so below the city. Arriving at the camp we were marched to the barracks of Company I, Third Battalion, First Massachusetts cavalry, to which company we had been assigned.

When we entered the barracks we were greeted with cries of “fresh fish,” etc., by the “old soldiers,” some of whom had reached camp only a few days before our arrival. We accepted the situation, and were ready as soon as we had drawn our uniforms to join in similar greetings to later arrivals. The barracks were one-story board buildings. They would shed rain, but the wind made itself at home inside the structures when there was a storm, so there was plenty of ventilation. The bunks were double-deckers, arranged for two soldiers in each berth.

“I'm not going to sleep in that apple bin without you give me a bed,” said Taylor to the corporal who pointed out our bunks.

“Young man, do you know who you're speaking to?” thundered the corporal.

“No; you may be the general or the colonel or nothing but a corporal—”

“'Nothing but a corporal!' I'll give you to understand that a corporal in the First Massachusetts cavalry is not to be insulted. You have no right to speak to me without permission. I'll put you in the guard house and prefer charges against you.”

“See here,” said Taylor. “Don't you fool with me. If you do I'll cuff you.”

“Mutiny in the barracks,” shouted a lance sergeant who heard Giles's threat to smite the corporal.

The first sergeant came out of a little room near the door, and charged down toward us with a saber in his hand.

“What's the trouble here?” he demanded.

“This recruit threatened to strike me,” replied the corporal.

“And he threatened to put me in the guard house for saying I wouldn't sleep in that box without a bed,” said Taylor.

“Did you ever hear the articles of war read?” asked the sergeant.

“No, sir.”

“Well, then, we'll let you go this time; but you've had a mighty narrow escape. Had you struck the corporal the penalty would have been death. Never talk back to an officer.”

“Golly! that was a close call,” whispered Taylor, after he had crawled into his bunk.

We each had a blanket issued to us for that night, but the next day straw ticks were filled, and added to our comfort. Waterman and I took the upper bunk, and Giles slept downstairs alone until he paired with Theodore C. Hom of Williamstown, another new-comer.

One of the most discouraging experiences that a recruit was called upon to face before he reached the front was the drawing of his outfit—receiving his uniform and equipments. I speak of cavalry recruits. If there ever was a time when I felt homesick and regretted that I had not enlisted in the infantry it was the morning of the second day after our arrival at Camp Meigs. I recall no one event of my army life that broke me up so completely as did this experience. I had drawn a uniform in the Griswold cavalry at Troy before my father appeared on the scene with a habeas corpus, but I had not been called on to take charge of a full set of cavalry equipments. If I had been perhaps the second attack of the war fever would not have come so soon.

A few minutes after breakfast the first sergeant of Company I came out from his room near the door and shouted:

“Attention!”

“Attention!” echoed the duty sergeants and corporals in the barracks.

“Recruits of Company I who have not received their uniforms fall in this way.”

A dozen “Johnny come Latelys,” including the Berlin trio, fell in as directed. The sergeant entered our names in a memorandum book. Then we were turned over to a corporal, who marched us to the quartermaster's office where we stood at attention for an hour or so while the requisition for our uniforms was going through the red-tape channels. Finally the door opened, and a dapper young sergeant with a pencil behind his ear informed the corporal that “all's ready.”

The names were called alphabetically, and I was the first of the squad to go inside to receive my outfit.

“Step here and sign these vouchers in duplicate,” said the sergeant.

I signed the papers. The sergeant threw the different articles of the uniform and equipments in a heap on the floor, asking questions and answering them himself after this fashion:

“What size jacket do you wear? No. 1. Here's a No. 4; it's too large, but you can get the tailor to alter it.

“Here's your overcoat; it's marked No. 3, but the contractors make mistakes; I've no doubt it's a No. 1.

“That forage cap's too large, but you can put paper in the lining.

“Never mind measuring the trousers; if they're too long you can have 'em cut off.

“The shirts and drawers will fit anybody; they're made that way.

“You wear No. 6 boots, but you'll get so much drill your feet'll swell so these No. 8's will be just the fit.

“This is your bed blanket; don't get it mixed with your horse blanket.

“I'll let you have my canteen and break in the new one; mine's been used a little and got jammed a bit, but that don't hurt it.

“This is your haversack; take my advice and always keep it full.

“This white piece of canvas is your shelter tent; it is warranted to shelter you from the rain if you pitch it inside a house that has a good roof on it.

“These stockings are rights and lefts.

“Here's your blouse. We're out of the small numbers, but it is to be worn on fatigue and at stables, so it's better to have plenty of room in your blouse.

“You will get white gloves at the sutler's store if you've got the money to settle. He'll let you have sand paper, blacking, brushes, and other cleaning materials on the same terms.

“Here's a rubber poncho.

“Let's see! that's all in the clothing line. Now for your arms and accoutrements!”

I appealed to the sergeant:

“Let me carry a load of my things to the barracks before receiving my arms and other fixings?”

“Can't do it—take too much time; and if you did go over with part of your outfit, somebody'd steal what you left in the barracks before you returned with the rest.”

“Go it, then,” I exclaimed in despair, and the sergeant continued:

“This carbine is just the thing to kill rebels with if you ever get near enough to them. It's a short-range weapon, but cavalrymen are supposed to ride down the enemy at short range.

“The carbine sling and swivel attaches the carbine over your shoulder.

“This cartridge box will be filled before you go on the skirmish line; so will the cap pouch.

“This funny-looking little thing with a string attached is a wiper with which to keep your carbine clean inside.

“The screw-driver will be handy to take your carbine apart, but don't do it when near the enemy. They might scoop you in before you could put your gun together.

“Your revolver is for short-range work. You can kill six rebels with it without reloading, if the rebels will hold still and you are a crack shot. You can keep the pistol in this holster which attaches to your waist-belt, as does also this box for pistol cartridges.

“These smaller straps are to hold your saber scabbard to the waist-belt, and this strap goes over the shoulder to keep your belt from slipping down around your heels.

“This is your saber inside the scabbard. I've no doubt it's inscribed 'Never draw me without cause or sheathe me with dishonor,' but we can't stop to look at it now. If it isn't inscribed, ask your first sergeant about it. The saber knot completes this part of the outfit. The saber is pretty big for you, but we're out of children's sizes. The horse furniture comes next.”

“Will you please let Taylor and Waterman come in here and help me?” I petitioned to the sergeant.

“Everybody for himself is the rule in the army,” said the sergeant. “Tie up your clothing and arms in your bed blanket. You can put your horse furniture in your saddle blanket.”

Section 1,620 of the “Revised United States Army Regulations of 1861, with an Appendix Containing the Changes and Laws Affecting Army Regulations and Articles of War to June 25, 1863,” reads as follows:

“A complete set of horse equipments for mounted troops consists of 1 bridle, 1 watering bridle, 1 halter, 1 saddle, 1 pair saddle-bags, 1 saddle blanket, 1 surcingle, 1 pair spurs, 1 curry-comb, 1 horse brush, 1 picket pin, and 1 lariat; 1 link and 1 nose bag when specially required.”

The section reads smoothly enough. There is nothing formidable about it to the civilian. But, ah me! Surviving troopers of the great conflict will bear me out when I say that section 1,620 aforesaid, stands for a great deal more than it would be possible for the uninitiated to comprehend at one sitting. The bridle, for instance, is composed of one headstall, one bit, one pair of reins. And the headstall is composed of “1 crown piece, the ends split, forming 1 cheek strap and 1 throat lash billet on one side, and on the other 1 cheek strap and l throat lash, with 1 buckle,.625-inch, 2 chapes and 2 buckles,.75-inch, sewed to the ends of cheek piece to attach the bit; 1 brow band, the ends doubled and sewed from two loops on each end through which the cheek straps and throat lash and throat lash billet pass.” So much for the headstall. It would take three times the space given to the headstall to describe the bit, and then come the reins. The watering bridle “is composed of 1 bit and 1 pair of reins.” The halter's description uses up one third of a page. “The saddle is composed of 1 tree, 2 saddle skirts, 2 stirrups, 1 girth and girth strap, 1 surcingle, 1 crupper.” Two pages of the regulations are required to describe the different pieces that go to make up the saddle complete, and which include six coat straps, one carbine socket, saddle skirts, saddle-bags, saddle blanket, etc. The horse brush, curry-comb, picket pin, lariat, link and nose bag all come in for detailed descriptions, each with its separate pieces.

Let it be borne in mind that all these articles were thrown into a heap on the floor, and that every strap, buckle, ring and other separate piece not riveted or sewed together was handed out by itself, the sergeant rattling on like a parrot all the time, and perhaps a faint idea of the situation may be obtained. But the real significance of the event can only be understood by the troopers who “were there.”

As I emerged from the quartermaster's office I was a sight to behold. Before I had fairly left the building my bundles broke loose and my military effects were scattered all around. By using the loose straps and surcingle I managed to pack my outfit in one bundle. But it was a large one, just about all I could lift.

When I got into the barracks I was very much discouraged. What to do with the things was a puzzle to me. I distributed them in the bunk, and began to speculate on how I could ever put all those little straps and buckles together. The more I studied over it the more complicated it seemed. I would begin with the headstall of the bridle. Having been raised on a farm I had knowledge of double and single harness to some extent, but the bridles and halters that I had seen were not of the cavalry pattern. After I had buckled the straps together I would have several pieces left with no buckles to correspond. It was like the fifteen-puzzle.

As I was manipulating the straps Taylor arrived with his outfit. He threw the bundle down in the lower bunk, and exclaimed:

“I wish I'd staid to home.”

“So do I, Giles.”

“Where's Theodore?”

“I haven't seen him since I left him at the quartermaster's.”

“He got his things before I did and started for the barracks.”

Taylor left his bundle and went in search of Hom who was found near the cook-house. His pack had broken loose, and he was too much disgusted to go any further. Taylor assisted him, and they reached the bunk about the time Waterman arrived. We held a council of war, and decided to defer action on the horse furniture till the next day.

“We'll tog ourselves out in these soldier-clothes and let the harness alone till we're ordered to tackle it,” said Taylor, and we all assented.

“Attention!”

The orderly sergeant again appeared.

“The recruits who have just drawn their uniforms will fall in outside for inspection with their uniforms on in ten minutes!”

There was no time for ceremony. Off went our home clothes and we donned the regulation uniforms. Four sorrier-looking boys in blue could not have been found in Camp Meigs. And we were blue in more senses than one. My forage cap set down over my head and rested on my ears. The collar to my jacket came up to the cap, and I only had a “peek hole” in front. The sleeves of the jacket were too long by nearly a foot, and the legs of the pantaloons were ditto. The Government did not furnish suspenders, and as I had none I used some of the saddle straps to hold my clothes on. Taylor could not get his boots on, and Hom discovered that both of his boots were lefts. He got them on, however. When Waterman put on his overcoat it covered him from head to foot, the skirts dragging the floor. Before we had got on half our things the order came to “fall in outside,” and out we went. Taylor had his Government boots in his hands, as a corporal had informed him that if he turned out with citizen's boots on after having received his uniform he would be tied up by the thumbs. So he turned out in his stocking feet.

We were “right dressed” and “fronted” by the first sergeant, who reported to the captain that the squad was formed. The captain advanced and began with Taylor, who was the tallest of the squad, and therefore stood on the right.

“Where are your boots?”

“Here,” replied the frightened recruit, holding them out from under the cape of his great coat.

“Fall out and put them on.”

“I can't.”

“Why not?”

“I wear nines and these are sevens.”

“Corporal, take this man to the quartermaster's and have the boots changed.”

Taylor trotted off, pleased to get away from the officer, who next turned his attention to Hom.

“What's the matter with your right foot; are you left-handed in it?”

“No, sir; they gave me both lefts.”

“Sergeant, send this man to the quartermaster's and have the mistake rectified.”

Waterman was next in line.

“Who's inside this overcoat?” demanded the captain. “It's me, sir—private Waterman.”

“Couldn't you get a smaller overcoat?”

“They said it would fit me, and I had no time to try it on.”

“Sergeant, have that man's coat changed at once. Fall out, private Waterman.”

Then came my turn. The captain looked me over. My make-up was too much for his risibility.

“Where did you come from?” he asked, after the first explosion.

“Berlin.”

“Where's that?”

“York State.”

“Well, you go with the sergeant to the quartermaster and see if you can't find a rig that will come nearer fitting you than this outfit.”

I was glad to obey orders, and after the captain's compliments had been presented to the quartermaster, directions were given to supply me with a uniform that would fit. Although the order could not be literally complied with, I profited by the exchange, and the second outfit was made to do after it had been altered somewhat by a tailor, and the sleeves of the jacket and the legs of the trousers had been shortened.

The captain did not “jump on us” as we had expected. 'The self-styled old soldiers had warned us that we would be sent to the guard house. The captain had seen service at the front, and had been through the mill as a recruit when the First Battalion was organized. He knew that it was not the fault of the privates that their clothes did not fit them. This fact seemed to escape the attention of many commissioned officers, and not a few recruits were censured in the presence of their comrades by thoughtless captains, because the boys had not been built to fill out jackets and trousers that had been made by basting together pieces of cloth cut on the bias and every other style, but without any regard to shapes, sizes or patterns.

The Buglers' Drill—Getting Used to the Calls—No Ear for Music—A Visitor from Home—A Basket full of Goodies—Taking Tintypes—A Special Artist at the Battle of Bull Run—Horses for the Troopers—Reviewed by a War Governor—Leaving Camp Meigs—A Mother's Prayers—The Emancipation Proclamation—The War Governors' Address.

HOULD there be living to-day a survivor of Sheridan's Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac who can, without shuddering, recall the buglers' drill, his probationary period on earth must be rapidly drawing to a close. I do not mean the regular bugle calls of camp or those sounded on company or battalion parade. I refer to the babel of bugle blasts kept up by the recruit “musicians” from the sounding of the first call for reveille till taps. A majority of the boys enlisted as buglers could not at first make a noise—not even a little toot—on their instruments, but when, under the instruction of a veteran bugler, they had mastered the art of filling their horns and producing sound they made up for lost time with a vengeance. And what a chorus! Reveille, stable call, breakfast call, sick call, drill call retreat, tattoo, taps—all the calls, or what the little fellows could do at them, were sounded at one time with agonizing effect.

The first sergeant of Company I said to me one day while we were in Camp Meigs:

“The adjutant wants more buglers, and he spoke of you as being one of the light weights suitable for the job. You may go and report to the adjutant.”

“I didn't enlist to be a bugler; I'm a full-fledged soldier.”

“But you're young enough to bugle.”

“I'm twenty-one on the muster-roll. I want to serve in the ranks.”

“Can't help it; you'll have to try your hand.”

I reported to the adjutant as directed, and was sent with a half-dozen other recruits to be tested by the chief trumpeter. After a trial of ten minutes the instructor discovered that there was no promise of my development into a bugler, and he said with considerable emphasis:

“You go back mit you to de adjutant and tell him dot you no got one ear for de music.”

I was glad to report back to the company, for I preferred to serve as a private.

The recruits soon became familiar with the sound of the bugle. The first call in the morning was buglers' call—or first call for reveille. The notes would be sounding in the barracks when the first sergeant, all the duty sergeants and the corporals would yell out:

“Turn out for reveille roll-call!”

“Be lively, now—turn out!”

As a result of this shouting by the “non-coms” the boys soon began to pay no attention to the bugle call, but naturally waited till they heard the signal to “turn out” given by the sergeants and corporals. And in a very short time they ceased to hear the bugle when the first call was sounded.

In active service in the Army of the Potomac so familiar with the calls did the soldiers become that when cavalry and infantry were bivouacked together, and the long roll was sounded by the drummers, it would not be heard by the troopers, and when the cavalry buglers blew their calls the foot soldiers would sleep undisturbed. In front of Petersburg troops would sleep soundly within ten feet of a heavy battery that was firing shot and shell into the enemy's works all night. But let one of the guards on the line of breastworks behind which they were “dreaming of home” discharge his musket, and the sleepers would be in line ready for battle almost in the twinkling of an eye. And let the cavalry trumpeter make the least noise on his bugle, and the troopers would hear it at once.

A few weeks before our battalion left Camp Meigs for the front Mrs. E. L. Waterman of Berlin, mother of Irving Waterman, paid us a visit. She brought with her a basket full of goodies. Home-made pies, bread, butter, cheese, cookies and fried cakes were included in the supplies. She took up her quarters at the picture gallery of Mr. Holmes, the camp photographer, and we went to see her as often as our duties would permit. She brought us socks knit by our friends at home, and many articles for our comfort. About the first thing she said was: “My boys, what do they give you to eat?”

“Bread and meat and beans and coffee,” we answered.

“No butter?”

“No.”

“I thought not. I had heard the soldiers had to eat their bread without butter, with nothing but coffee to wash it down, so I brought you a few pounds of butter.”

And the dear woman remained at the gallery, and Irving and I would drop over and eat the good things she fixed for us. If we had taken our commissary stores to the barracks they would have been stolen.

Mrs. Waterman asked Irving and myself to have our pictures taken. Neither of us had ever been photographed or tintyped, but we took kindly to the idea. We sat together, and the picture, a tintype, was pronounced an excellent likeness. What a trying performance it was, though! We were all braced up with an iron rest back of the head, and told to “look about there—you can wink, but don't move.” Of course the tintype presented the subject as one appears when looking into a mirror. The right hand was the left, and our buttons were on the wrong side in the picture. But Mrs. Waterman declared the tintype to be “as near like them as two peas,” and we accepted her verdict. The dear old lady has kept that picture all these years.

The soldier boys resorted to all sorts of expedients to “beat the machine.” That is, to so arrange their arms and accoutrements that when the tintype was taken it would not be upside down or wrong end to. To this end the saber-belt would be put on wrong side up so that the scabbard would hang on the right side—that would bring it on the left side, where it belonged in the picture. I tried that plan one day and then stood at “parade rest,” with the saber in front of me. I put back my left foot instead of my right to stand in that position, and when the picture was presented, I congratulated myself that I had made a big hit. But when I showed it to an old soldier in the company he humiliated me by the remark:

“It's all very fine for a recruit, but a soldier wouldn't hold his saber with his left hand and put his right hand over it at parade rest.”

Sure enough. I had changed my feet to make them appear all right, but had forgotten the hands. But recruits were not supposed to know everything on the start.

We had photographs taken as well as tintypes. But the art of photography has greatly improved since the war. Most of the photographs of that day that I have seen of late are badly faded, and it is next to impossible to have a good copy made. Not so with the tintypes. They remain unfaded, and excellent photographic copies can be secured. In many a home to-day hang the pictures of the soldier boy, some of them life-sized portraits copied from the tintypes taken in the days of the war.

I know homes where the gray-haired mothers still cling to the little tintype picture—the only likeness they have of a darling boy who was offered as a sacrifice for liberty. How tenderly the picture is handled! How sacredly the mother has preserved it! The hinges of the frame are broken—worn out with constant opening. The clasp is gone. The plush that lined the frame opposite the picture is faded and worn. But the face of the boy is there. Surviving veterans understand something of the venerable lady's meaning when she puts the picture to her lips and with tears in her eyes says:

“Yes, he was only a boy. I couldn't consent to let him go, and I couldn't say no. I could only pray that he would come back to me—if it were God's will. He didn't come back. But they said he did his duty. He died in a noble cause, but it was hard to say 'Thy will be done,' at first, when the news came that he'd been killed. I'm so thankful I have his picture—the only one he ever had taken. He was a Christian boy, and they wrote me that his last words as his comrades stood about him under a tree where he had been borne, were, that he died in the hope of a glorious resurrection, and that mother would find him in Heaven to welcome her when she came. There's comfort in that. And I'll soon be there. I shall meet my boy again, and there will be no more separation. No more cruel rebellions.” The early war-time pictures are curiosities to-day, particularly to veterans who study them. Not a few of the special artists of the first year of the war seemed to have gained whatever knowledge of the appearance of troops in battle array that they had from tintype pictures. I have before me as I write, a battle scene “sketched by our special artist at the front.” The officers all wear their swords on the right side, and in the foreground is an officer mounting his horse from the off side—a feat never attempted in military experience but once, to my knowledge, and then by a militia officer on the staff of a Troy general, since the war. In some of these pictorial papers of the early war-days armies are represented marching into battle in full-dress uniform and with unbroken step and perfect alignment.

One thing, however, always puzzled me in these pictures—before I went to war—and that was how the infantry could march with measured tread—regulation step of twenty-eight inches, and only one hundred and ten steps per minute—and keep up with the major-generals and other officers of high rank who appeared in front of their men, and with their horses on a dead run in the direction of the enemy! These heroic leaders always rode with their hats in one hand and their swords in the other, so there was no chance for them to hold in their horses. But the puzzle ceased to be a puzzle when I reached the front. I found that the special artists had drawn on their imagination instead of “on the spot,” and that it was not customary for commanding generals to get in between the contending lines of battle and slash right and left and cut up as the artists had represented. In the majority of cases, great battles were fought by generals on both sides who were in position to watch, so far as possible, the whole line of battle, and to be ready to direct such movements and changes as were demanded by the progress of the fight. To do this they must necessarily be elsewhere than in front of their armies, riding down the enemy's skirmishers, and leaping their horses over cannon.

It is possible, however, that the special artists did not fully understand the danger to which a commanding general would be exposed, galloping around on his charger between the armies just coming together in a terrible clash. At any rate, the specials were willing to take their chances with their heroes—on paper. I have in my possession a picture of the “Commencement of the Action at Bull Run—Sherman's Battery Engaging the Enemy's Masked Battery.” In this picture, sketched by an artist whose later productions were among the best illustrations of actual warfare, the officers are, very considerately, placed in rear of the battery. But in front of the line of battle, in advance of the cannon that are belching forth their deadly fire, stands the special artist, sketching “on the spot.”

There was a good deal of stir in Camp Meigs the day that horses were issued to the battalion. The men were new and so were the horses. It did not take a veteran cavalryman but a day or two to break in a new horse. But it was different with recruits. The chances were that their steeds would break them in.

I had had some experience with horses on a farm—riding to cultivate corn, rake hay and the like—but I had never struggled for the mastery with a fiery, untamed war-horse. Our steeds were in good condition when they arrived at the camp, and they did not get exercise enough after they came to take any of the life out of them. The first time we practiced on them with curry-comb and brush, the horses kicked us around the stables ad libitum. One recruit had all his front teeth knocked out. But we became better acquainted with our chargers day by day, and although we started for Washington a few days after our horses had been issued, some of us attained to a confidence of our ability to manage the animals that was remarkable, considering the fact that we were thrown twice out of three times whenever we attempted to ride.

One day orders came for us to get ready to go to the front. None but old soldiers can appreciate the feelings of recruits under such circumstances. All was bustle and confusion. There was a good deal of the hip, hip, hip, hurrah! on the surface, but there was also a feeling of dread uncertainty—perhaps that expresses it—in the breasts of many of the troopers. They would not admit it, though. The average recruit was as brave as a lion to all outward appearances, and if he did have palpitation of the heart when orders came to go “On to Richmond”—as any advance toward the tront was designated—the fact was not given out for publication.

The first thing in order was a general inspection to satisfy the officers, whose duty it was to see that regiments sent out from the Old Bay State were properly armed and equipped, that we were in a condition to begin active service. After all our belongings were packed on our saddles in the barracks, before we took them over to the stables to saddle up, the department commander with his inspecting officers examined our pack kits. As originally packed, the saddles of a majority of the troopers were loaded so heavily that it would have required four men to a saddle to get one of the packs on the horse's back. When the inspection was completed each trooper could handle his own saddle.

The following articles were thrown out of my collection by the inspectors:—

Two boiled shirts; one pair calfskin shoes; two boxes paper collars; one vest; one big neck scarf; one bed quilt; one feather pillow; one soft felt hat; one tin wash basin; one cap—not regulation pattern; one camp stool—folding; one blacking brush—extra; two cans preserves; one bottle cologne; one pair slippers; one pair buckskin mittens; three fancy neckties; one pair saddle-bags—extra; one tin pan; one bottle hair oil; one looking-glass; one checker-board; one haversack—extra—filled with home victuals; one peck bag walnuts; one hammer.

Some of the boys had packed up more extras than I had, and it went against the grain to part with them. But the inspectors knew their business—and ours, too, better than we, as we subsequently discovered—and we were made to understand that we were not going on a pleasure excursion. It is hardly necessary to say that there was scarcely an article thrown out by the inspectors that the soldiers would not have thrown away themselves on their first expedition into the enemy's country.

After we had been inspected and trimmed down by the officers, we were reviewed by Governor John A. Andrew. He was attended by his staff, the department commander and other officers. Each company was drawn up in line in its barracks—it was sleeting outside. As the governor came into our quarters, the captain gave the command, “Uncover!” and the company stood at attention as the chief executive of the Old Bay State walked slowly down the line, scanning the faces of the men.

I remember that the governor looked at me with a sort of “Where-did-you-come-from, Bub?” expression, and I began to fear that my time had come to go home. The governor said to a staff officer:

“Some of the men seem rather young, Colonel!”

“Yes, sir; the cavalry uniform makes a man look younger than he is.”

“I see. They are a fine body of men, and I have no doubt we shall hear of their doing good service at the front.”

A few words of encouragement were spoken by the governor, and he passed on to the barracks of the next company.

It strikes me that Governor Andrew reviewed us again as we were marching from the barracks to the railroad station, but I am not clear on this point. I know there was a good deal of martial music, waving of flags, cheering and speech-making by somebody. Our horses claimed our undivided attention till after we had dismounted and put them aboard the cars. On the way down to the railroad an attempt was made somewhere near the barracks to form in line, so that we could be addressed by the governor or some other dignitary. It was a dismal failure. Our steeds seemed to be inspired by “Hail to the Chief,” “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” and other patriotic tunes played by the band, and they pranced around, stood upon their hind legs and pawed the air with their fore feet, to the great terror of the recruits and the delight of all the boys in the neighborhood who had gathered to witness our departure. How the boys shouted!

“Hi, Johnny, it's better'n a circus!”

“Guess 'tis—they don't fall off in a circus; they just make b'lief.”

“Well, these fellows stick tight for new hands.”

It was fun for the boys—the spectators—but just where the laugh came in the recruits failed to discover. I was told that the governor—or somebody—gave us his blessing as we rode by the reviewing officer, but I have no personal knowledge on the subject.

After we had put our horses on board we waited a few minutes before entering the cars while the other companies were boarding the train. There was a chain of sentinels around us, and Mrs. Waterman was outside the line. She caught sight of us as we stood there, and she advanced toward us.

“Halt—you can't go through here!” commanded one of the sentinels.

“I must go through.”

“But my orders—”

“I don't care; my boys are there, and I'm going to speak to them again.”

She came through and gave us her parting blessing once more.

“Boys, I'll pray God to keep you and bring you both back to your mothers—God bless you; good-by.” The mother's prayers were answered. Her son and his tentmate were spared to return at the close of the war.

There was a scramble to secure seats when orders were given to board the cars. Good-bys were said. Mothers, wives and sweethearts were there, and with many it was the last farewell. The whistle blew, the bells rang, the band played, the troops remaining at Camp Meigs cheered and we cheered back. The train moved away from the station, and we were off for the front.

I never saw Governor Andrew again, but I recall his appearance as he reviewed our company in the barracks very distinctly. I observed that while inspecting officers paid more attention to the arms and accoutrements of the men the governor was particular in looking into the faces of the recruits, to satisfy himself, no doubt, that they could be trusted to uphold the honor of the State when the tug of war should come. John A. Andrew was one of the “war governors” whose loyal support of President Lincoln's emancipation programme held the Northern States in line when the time came for the President to issue the proclamation that freed the slaves of the States in rebellion against the Government.

The proclamation was promulgated September 22, 1862, a few days after the battle of Antietam. It is on record that Lincoln had made the draft of the document in July, and had held it, waiting for a Union victory, that he might give it to the country at the same time that a decisive defeat of the rebels was announced. The second battle of Bull Run came, and Pope's shattered army retreated into the works around the national capital. Lee, with his victorious followers, crossed the Potomac into Maryland. The Confederate chief hoped to rally the disloyal element in that State and along the border under the rebel flag. It began to look as though the victory Lincoln was waiting for would never come. It was one of the darkest hours of the conflict. What would have been the effect of issuing the Emancipation Proclamation at that time? The rebels had invaded the North! The Union army had been defeated—everything seemed to be going to destruction!

Lincoln is credited with saying in respect of the rebels crossing the Potomac just before the battle of Antietam:

“I made a solemn vow before God, that if General Lee were driven back from Maryland, I would crown the result by a declaration of freedom to the slaves.”

September 24, 1862, two days after the proclamation was issued, Governor Andrew, with the governors of other loyal States, at a meeting at Altoona, Penn., adopted an address to the President that must have set at rest any doubts the chief magistrate may have had that his policy was the policy of the loyal people of the North. The document was inspired and executed by patriots in whom the citizens of the loyal States reposed unbounded confidence. They declared:

“We hail with heartfelt gratitude and encouraged hope the proclamation of the President, issued on the 22d inst., declaring emancipated from their bondage all persons held to service or labor as slaves in rebel States where rebellion shall last until the first day of January ensuing.

“Cordially tendering to the President our respectful assurances of personal and official confidence, we trust and believe that the policy now inaugurated will be crowned with success, will give speedy and triumphant victories over our enemies, and secure to this nation and this people the blessing and favor of Almighty God. We believe that the blood of the heroes who have already fallen and those who may yet give up their lives to their country will not have been shed in vain.

“And now presenting to our chief magistrate this conclusion of our deliberations, we devote ourselves to our country's service, and we will surround the President in our constant support, trusting that the fidelity and zeal of the loyal States and people will always assure him that he will be constantly maintained in pursuing with vigor this war for the preservation of the national life and hopes of humanity.”

Arrival at Warrenton—Locating a Camp—Dog Tents—Building Winter Quarters—On Picket—A Stand-off with the Rebels—A Fatal Post—Alarm at Midnight—Bugle Calls—The Soldier's Sabbath—The Articles of War and the Death Penalty.

T rained the day the third battalion of the First Massachusetts cavalry arrived at Warrenton, Va., and it rained for three days, almost without a let-up, after we, reached our destination.

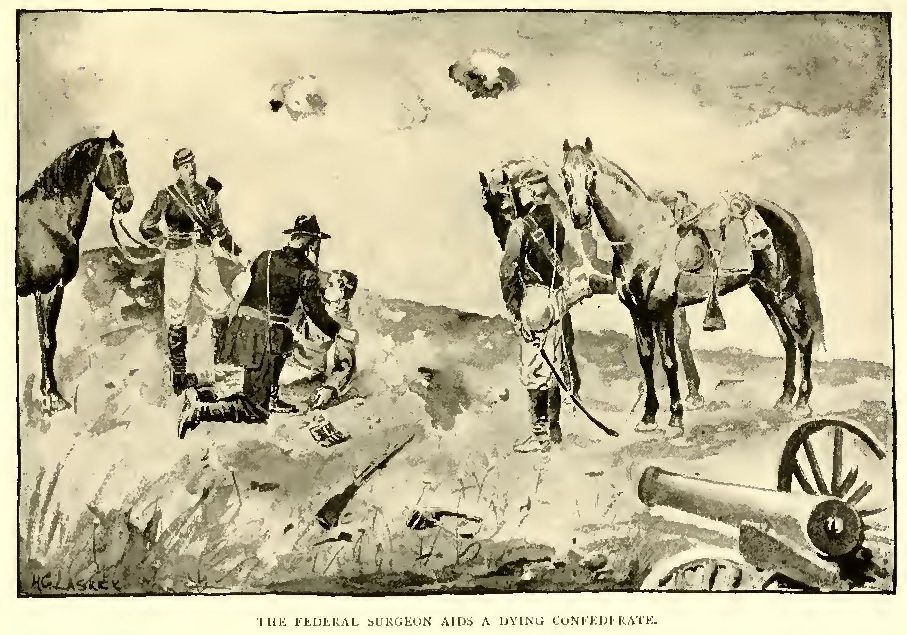

Recruits always received a hearty welcome at the front—the less the old soldiers had to do in the way of picket duty, the better they liked it. The recruits were—at first—ready to do all the duty, and the veterans were willing to let the new arrivals have their own way along this line. But after a few weeks of wear and tear at the front, the raw recruits could generally give the old soldiers points on dodging duty and feigning sickness, so as to have “excused from picket,” or “light duty” marked opposite their names on the sick book. These peculiarities of soldier-life were characteristic of camp and winter quarters. As a rule, when the troops were brought face to face with the “business of the campaign,” there was a sort of freemasonry among them. Then the veteran was ready to share his last cracker with the recruit, and they drank from the same canteen. An engagement with the enemy was sure to place all who stood shoulder to shoulder on a level. In the jaws of death, with comrades dropping on every hand, all were “boys,” and all were soldiers—comrades.

Our first night's experience at Warrenton was not calculated to inspire us with love for the place. When we arrived we were drawn up in line in front of headquarters.

“You will camp your men just south of that row of tents,” a brigade staff officer said to the major in command of our battalion. “You can pitch tents till such time as you can build winter quarters. Stretch your picket lines so as to leave proper intervals between your camp and the regiment next to it.”

The staff officer hurried back into his log-house, to get out of the rain. We broke into columns of fours, and were marched to the ground on which we were to build our winter quarters. The outlook was discouraging. The camp was laid out on a side hill, down which good-sized brooks of water were flowing. And the ground! It was like a bed of mortar. Next to prepared glue, Virginia mud is entitled to first prize for its adhesive qualities.

“See here,” exclaimed Taylor, “they're only just making fools of us. No general could order us to get off our horses and make camp in this mud-hole.”

Taylor's indiscretion was always getting him into trouble, and his talking in ranks this time secured him another tour of double duty.

Down came the rain, and we were in for it. In due time the horses were picketed and their nosebags put on. As soon as the animals were taken care of and fed, the weary troopers, drenched to the skin, were directed to “pitch tents!” The tents with which we were provided were known as shelter, or dog tents, the latter name being most popular, as they often failed to afford anything but a poor apology for shelter. Each soldier had half a tent—till he lost it. The half-tent was a piece of canvas about five feet by four, or somethinglike it. Along one edge was a row of buttonholes, and a little further back a row of buttons. Two pieces buttoned together were put over a ridge-pole, supported by two crotches, and the bottom edges of the tent were fastened to the ground by little cord loops through which sticks were driven. Both gable ends of the tent were open to the weather, but sometimes a third “bunkey” would be taken in, and one end of the tent closed up with his piece. The shelter tents were always too short at both ends. Think of a man like Corporal Goddard of our company, who was an inch or two over six feet, trying to “shelter” himself under such a contrivance. A man of medium height could find cover only by doubling himself up in the shape of a capital N, and it was necessary to “spoon it” where two or three attempted to sleep under one dog tent.

Waterman and I continued as bunkies. At Camp Stoneman, Taylor and Hom had occupied the upper bunk in our log-house, and the same quartette had decided to go together when we should build winter quarters at our new location. Hom was detailed for stable guard as soon as we dismounted, and Taylor, Waterman and myself concluded to pitch tents together.

The ground was so soft that the sticks would not hold, and the tent was blown down several times. All our blankets were wet. Long after dark, however, we made fast the tent as best we could, and crawled in. Taylor being the oldest and largest, was assigned by a majority vote of Waterman and myself, to the side from which the wind came. I took the middle. It was close quarters.

“I don't see what's the use of getting up to fix it again,” said Taylor, as the dog tent was blown down the third time after we had turned in. “I'm just as wet's I can be, and I'd rather sleep than get up again.”

I had managed to raise myself a few inches above the water. My saddle was under my head, and I had two canteens under my back. The water was running a stream between Waterman and Taylor.

“I'll sit up and hold the tent while you fellows sleep,” volunteered the genial Taylor the next time the tent went down.

There was nothing selfish about Taylor. After we had gone to sleep he “hadn't the heart to disturb us,” as he expressed it the next day, and when the wind shifted and there was a slight let-up in the deluge, he took the three pieces of tent, our rubber ponchos, saddle blankets and bed blankets and, selecting the dryest spot he could find on the side-hill, he rolled himself up in them and slept till reveille. Just before daybreak Waterman and I were drowned out, and sought shelter in an old brick building up on the hill.

The erection of log huts for winter quarters at Warrenton was no “joke.” We had to go on Water Mountain to cut the trees for building material. Then we waited our turn for teams and wagons to haul the logs.

It was thirteen days before we got our log-house built and our shelter tents nailed on for a roof. Two bunks, one over the other, were made of poles. Taylor and Hom had the upper bunk, while Waterman and I slept “downstairs.”

“There's more of Giles than there is of us,” suggested Waterman, “and we'll put him and Hom in the top bunk so that when it rains and the roof leaks they'll absorb a good deal of the water before it gets to us.”

Waterman and I chuckled over our success in securing the lower bunk, but one night when the upper bunk broke, and Taylor and Hom came tumbling down upon us, we realized, indeed, that there was a good deal more of Giles than there was of us.

We went on picket in our turn. The line ran along the top of Water Mountain for some distance, and we occasionally exchanged compliments with Mosby's men. The first night we were on picket, a little down to the south of the mountain, I went on duty at nine o'clock. The post was across a creek and near an old stone mill. It rained, sleeted and snowed during the night, and the creek filled up so that the “relief” could not cross over to my post when the time came to change the pickets. As a result I remained on post till daylight. It was one of the longest nights I ever put in during my army service.

Of course, every noise made by the wind was a bushwhacker. I was so thankful to find myself alive at daybreak that I forgot to growl at the corporal for not relieving me on time. When I unbosomed myself to Taylor, and told him how nervous I felt out there by the old mill, he laughed and said:

“Don't you never feel nervous again when you're caught in such a scrape, for, mark my word, no rebel, not even a 'gorilla' would be fool enough to go gunning for Yankee recruits such a night as last night was.” I found a good deal of comfort in Taylor's logical admonition after that when alone on picket in stormy weather.

Just over the divide on Water Mountain, on the side toward the rebel camp, was an old log shanty. We called it the block house. Our pickets occupied it by day, and the rebels had possession of it by night. This happened because the Union picket line was drawn in at night, and the pickets were posted closer together than during the day. Our line was advanced soon after daylight.

One morning when we galloped down to the block house from our reserve, we surprised the Johnnies. They had been a little late in getting breakfast, and their horses had their nosebags on. We were just as much surprised as they were, and we stood six to six. Carbines and revolvers were pointed, but no one fired.

“Give us time to put on our bridles and we'll vacate,” said the sergeant of the rebel picket.

“All right; go ahead,” our sergeant replied.

The Johnnies bridled their horses, mounted and rode down the mountain.

“We kept a good fire for you all,” the rebel sergeant remarked as they left.

“And you'll find it burning when you come back tonight,” was the Yankee sergeant's assuring reply.

After the rebels had got out of sight our boys began to feel that they had missed a golden opportunity to destroy a detachment of the Confederate army. We had longed for a “face-to-face” meeting with the rebels.

“I could have killed two rebels had I been allowed to shoot,” said Taylor.

“Who told you not to shoot?” demanded the sergeant.

“Well, nobody gave the order to fire. I had my gun cocked and if the rest of you had killed your man I'd killed mine.”

“Bu-bu-bu-but they had si-si-six t-t-to ou-ou-our si-si-six, di-di-didn't they?” interrupted Jack Hazelet, whose stammering always caused him to grow red in the face when he wanted to get a word in in time and couldn't.

“Yes; we stood six to six, but if each one of us had killed his man they would all be dead.”

“Je-je-jesso; bu-bu-bu-but di-di-didn't they ha-ha-have gu-gu-guns, t-t-too?”

“Of course they did.”

“Sup-po-po-posen they ha-ha-had ki-ki-killed 's mama-many f us a-a-as we di-di-did o-o-o-of th-th-them, wh-wh-where wo-wo-would wc-we-we b-b-be n-n-now? co-co-confound you!”

As we found that only two of our party had their carbines loaded when we surprised the rebels, we concluded that it was just as fortunate for us as it was for the enemy that the meeting had resulted in a stand-off, although Taylor insisted that if any one had given the command “fire” he would have killed his man. When his attention was called to the fact that his carbine was not loaded, he said:

“Well, I could have speared one of them with my sword before they could all get away.”

“Bu-bu-bu-but wh-wh-what wo-wo-would th-th-the re-re-reb be-be-been do-do-doing; yo-yo-you in-in-infernal blockhead!” exclaimed Hazelet, and Taylor subsided.

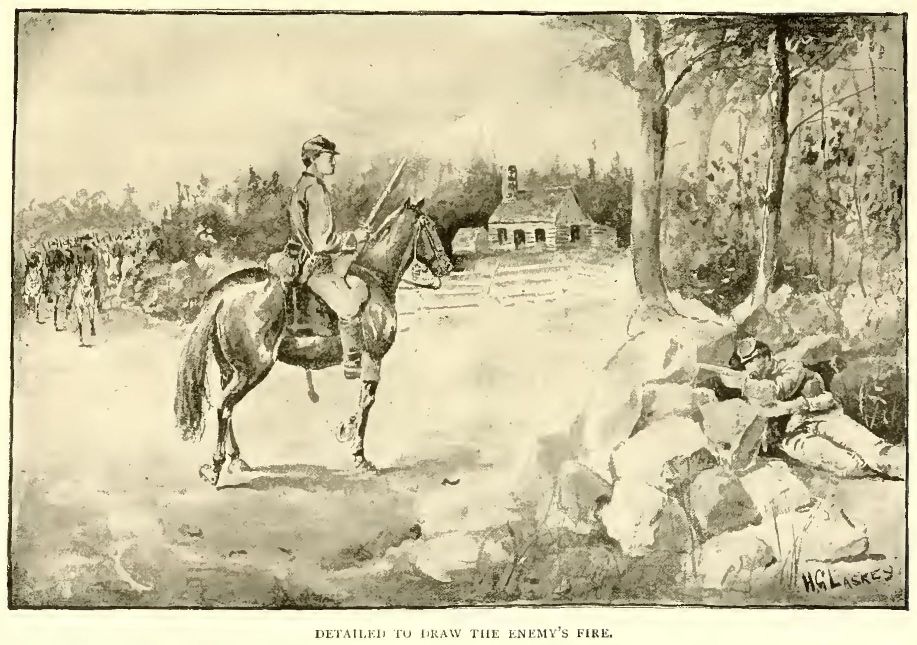

There was one picket post half-way down Water Mountain, toward the Federal camp, that was dreaded by all the boys. It was within three hundred yards of the picket reserve or rendezvous. There was an old wagon road winding through a narrow ravine, and a stone wall crossed at right angles with the road opposite the reserve. On either side of the ravine was thick underbrush, and just back a little were woods. We were informed that four pickets had been shot off their horses near the old tree. The bushwhackers would ride to within a few hundred yards of the stone wall, dismount and while one would remain with the horses another would crawl like a snake in the grass up behind the wall and pick off the Union cavalrymen. It was cold-blooded murder, committed at night, without cause or provocation. Let it be said to the credit of the Confederate rank and file, that the boys in butternut—the regularly organized troops—discountenanced the cowardly acts of the guerrillas and bushwhackers.

A soldier was shot on picket at the old tree one night, and our company relieved the company to which he belonged the next morning. The murdered trooper was strapped across his saddle and taken to camp for burial. When our boys were counted off for picket Taylor “drew the fatal number,” as it was called.

“If I'm murdered on post, boys,” he said, “don't bother about taking my carcass to camp. Bury me where I fall.”

Taylor made a poor attempt to appear unconcerned. But he was a droll sort of a boy. He continued:

“I've no doubt I was cut out for an avenger; so if any of you fellows want me to avenge your death just swap posts with me to-night. If any infernal gorilla steals up on you and takes your life, I pledge you that I'll follow him to Texas, but what I'll spill his gore.”

“I'd rather go unavenged than to take chances on that post from eleven o'clock to one o'clock to-night,” chorused several of Taylor's friends.

I had the post next to Taylor toward the reserve. The rain was falling, and it was dark down in the ravine. I could hear Taylor's horse champing his bit, and once my horse broke out with a gentle whinny, the noise of which startled me tremendously at first. And I have no doubt it operated the same on Taylor. Soon after that the rain let up and the clouds broke away so that the moon could be seen now and then. All at once there was a flash and a loud report.

“That's the last of poor Giles,” I exclaimed, as the sound of the shot reverberated through the ravine.

Then I rode toward Taylor's post as cautiously as I could. I was pleasantly startled by the challenge in his well-known voice:

“Who comes there?”

The reserve came galloping down the hill. After the usual challenges and answers had been given, the lieutenant inquired:

“Who fired that shot?”

“'Twas me,” replied Tavlor.

“What did you fire at?”

“A bushwhacker.”

“Where?”

“Over by the wall.”

“Did you see him?”

“Of course I did; you don't suppose I'd fire at the moon, do you?”

The reserve rode forward to the wall and a few hundred yards beyond. It was decided that it would be useless to follow the guerrillas in the darkness. The pickets were doubled, two men on a post, for the rest of the night. I was put on the same post with Taylor, and after the reserve had returned to the rendezvous I questioned him about the alarm:

“Are you sure you saw a live bushwhacker, Giles?”

“If I hadn't seen him I'd be dead now.”

“You didn't challenge him?”

“Well, I should say not. I saw him raise his head over the wall, just as the moon broke through a cloud. I first saw the glisten of his gun. Then I fired, and I believe I singed his hair, for I took good aim. If the moon had staid behind the clouds three seconds longer, the gorilla would 'a' had me sure. After I fired I heard him run, and then there were voices, followed by the noise of horses' hoofs as the bushwhackers galloped away. It was a close call for Taylor, but I tell you I sat with my carbine cocked and pointed at that wall all the time till the gorilla appeared. If my horse hadn't shied a little, that fellow would never have gone back to tell the story of his failure to murder another picket.”

The next day arrangements were made to surprise the guerrillas in the event of another visit. Two dismounted troopers were stationed behind the stone wall, within easy range of the opening down the road toward the rebel lines. But the bushwhackers did not return during our tour of picket.

It was never clearly explained why the post at the old tree had been used, when the picket could be so much more safely stationed up behind the wall. There were a good many things that seemed strange to privates, but whenever an enlisted man made an effort to suggest that the plan of operations of his superiors be revised or corrected, it did not take him long to discover that he had made “one big shackass of mineself,” as a recruit from Faderland expressed it when he was booted out of a sergeant's tent at Warrenton for simply informing the wearer of chevrons that in “Shermany the sergeants somedimes set up der lager mit de boys.”

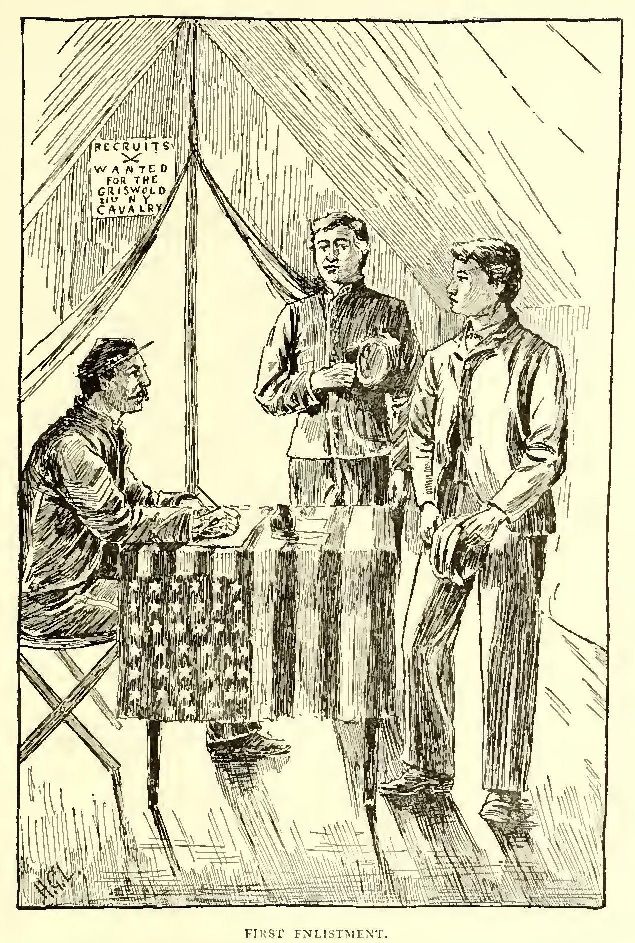

The experiences of the First Massachusetts cavalry at Warrenton during the winter were similar to those of other regiments in camp at that station. Some of us would have been fearfully homesick if we had found any spare time between calls. We scarcely had opportunity to answer letters from home, so thick and fast came the bugle blasts. One of our boys received a letter from his sweetheart, and she wondered what the soldiers could find to occupy their time—“no balls, no parties, no corn-huskings,” as she expressed it. Her soldier boy inclosed a copy of the list of calls for our every-day existence in camp, and when we were not on picket duty.

I have no doubt the dear girl was satisfied that her boy in blue would suffer little, if any, for the want of something to keep his mind occupied. As near as I can remember, the list of calls for each day's programme—except Sunday, when we had general inspection and were kept in line an hour or two extra—was as follows: