UNIQUE AND POPULAR WORKS FOR ALL

NATURE LOVERS.

Uniform with this Volume.

Wayside and Woodland

Blossoms

A Pocket Guide to British Wild Flowers for the Country Rambler.

(First and Second Series.)

With Clear Descriptions of 760 Species.

BY

EDWARD STEP, F.L.S.

And Coloured Figures of 257 Species by

MABEL E. STEP.

Wayside and Woodland

Trees

A Pocket Guide to the British Sylva.

BY

EDWARD STEP, F.L.S.

With 127 Plates from Original Photographs by

HENRY IRVING,

And 57 Illustrations of the Leaves, Flowers and Fruit by

MABEL E. STEP.

AT ALL BOOKSELLERS.

Full Prospectuses on application to the Publishers—

FREDERICK WARNE AND CO.

London: 15, Bedford Street, Strand.

New York: 36, East 22nd Street.

THE WAYSIDE

AND WOODLAND

SERIES

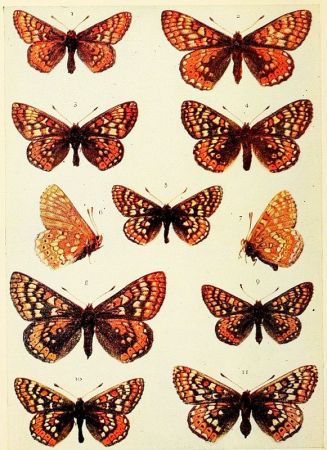

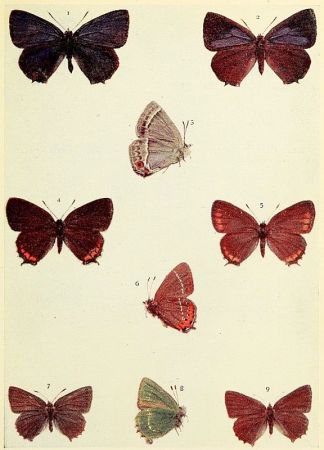

THE BUTTERFLIES OF THE

BRITISH ISLES

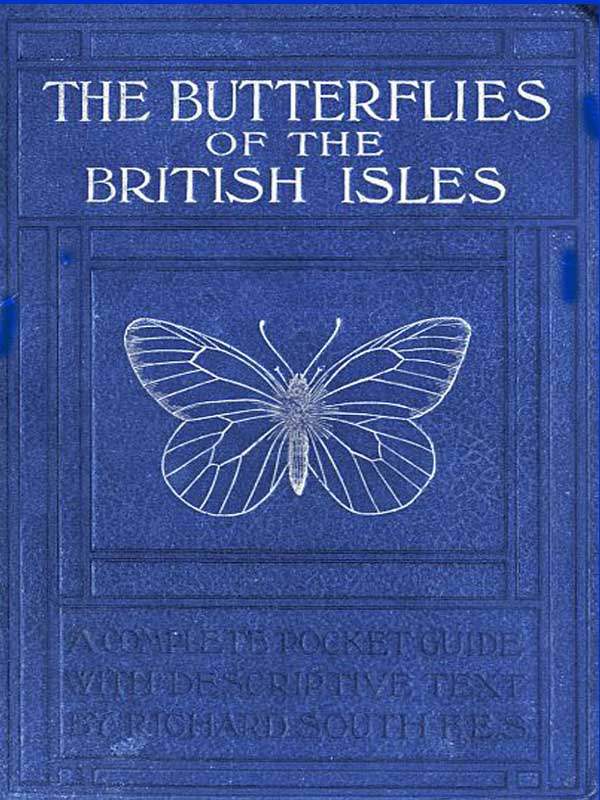

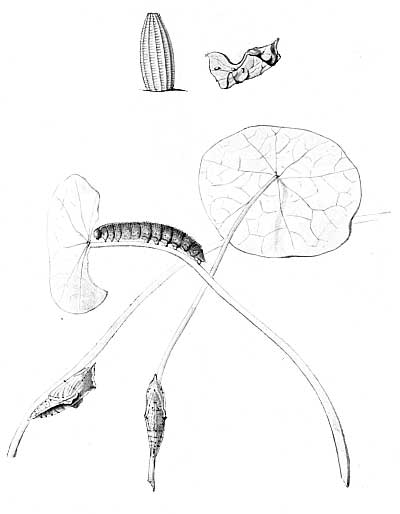

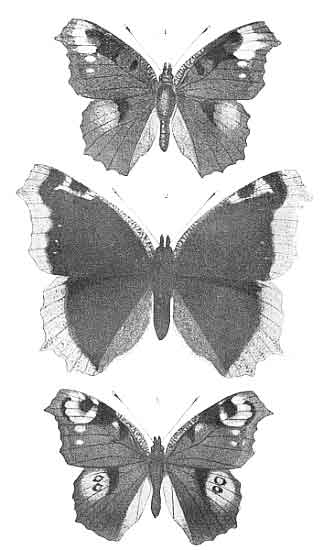

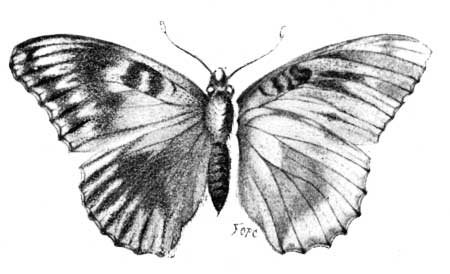

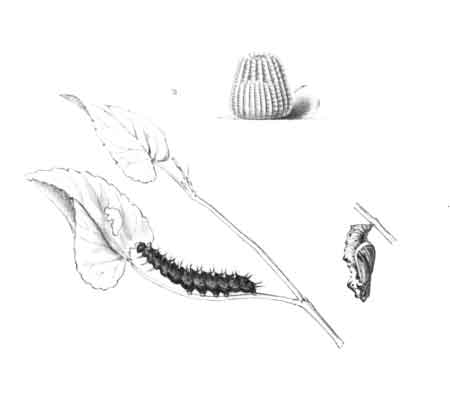

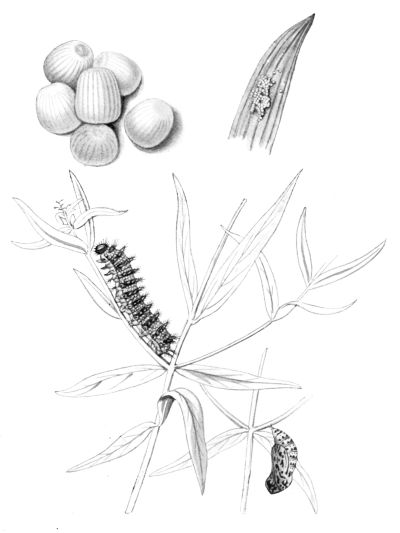

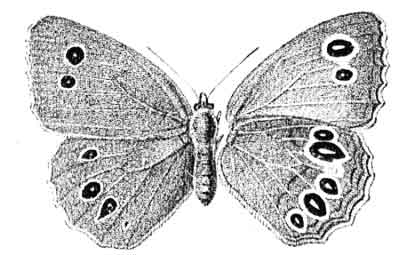

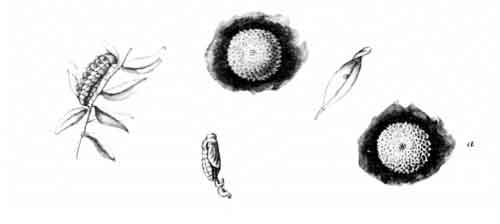

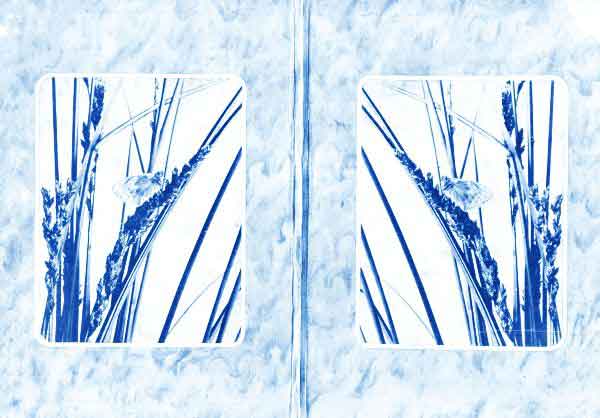

Pl. 1. Frontispiece.

Swallow-tail Butterfly.

Male and female, with caterpillars and chrysalids.

BY

RICHARD SOUTH, F.E.S.

EDITOR OF

"THE ENTOMOLOGIST," ETC.

WITH

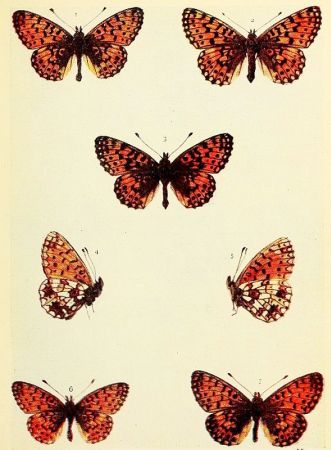

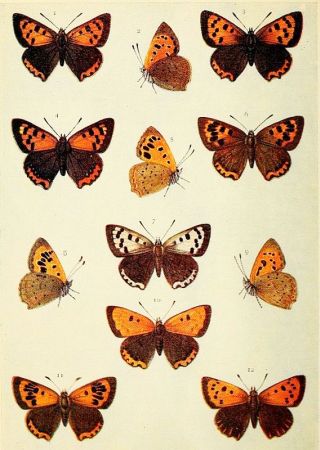

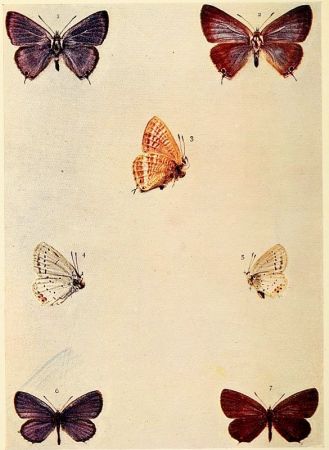

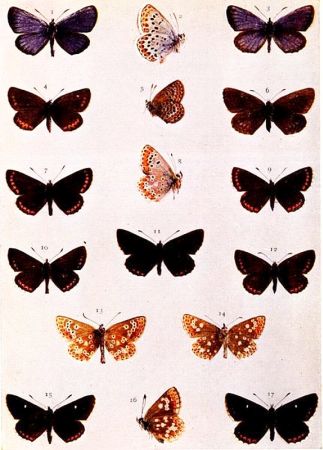

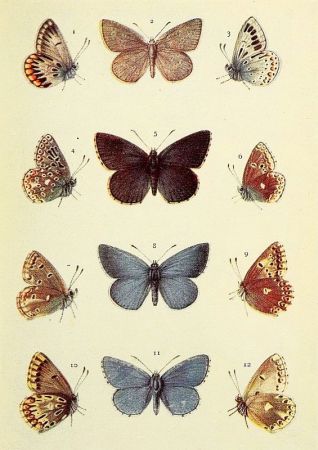

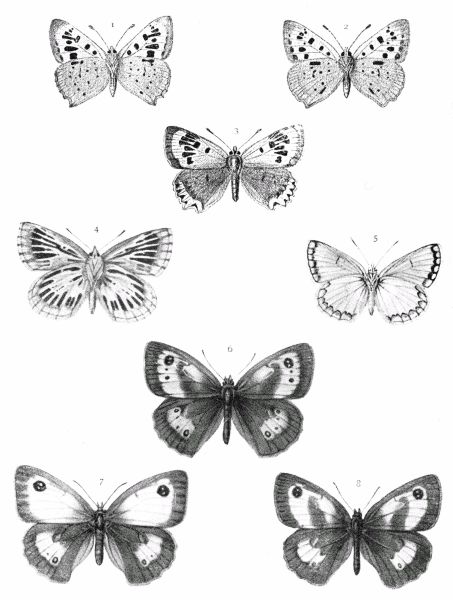

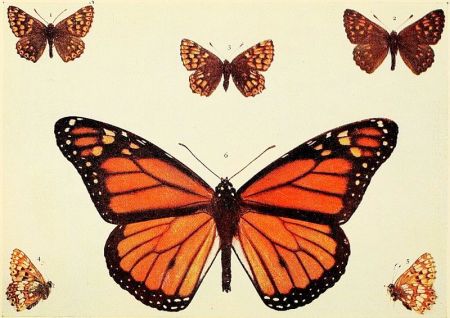

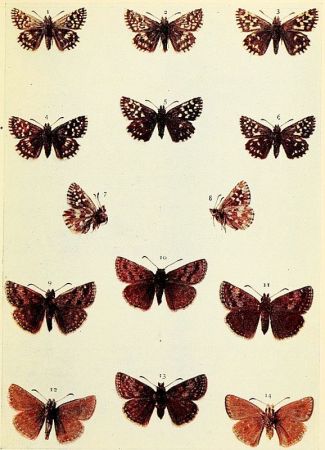

ACCURATELY COLOURED FIGURES

OF EVERY SPECIES AND MANY VARIETIES

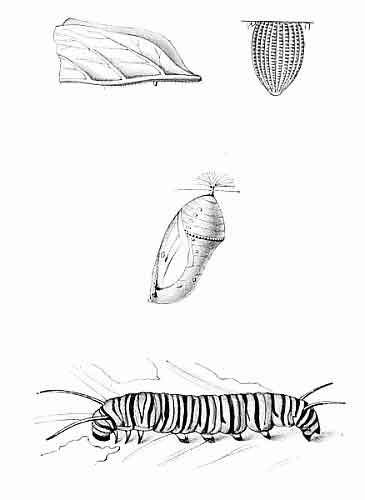

ALSO DRAWINGS OF EGG, CATERPILLAR

CHRYSALIS, AND FOOD-PLANT

LONDON

FREDERICK WARNE & CO.

AND NEW YORK

1906

(All rights reserved)

Few things add more enjoyment to a country ramble than a knowledge of the many and varied forms belonging to the animal and vegetable kingdoms that present themselves to the notice of the observing wayfarer on every side.

Almost every one admires the wild flowers that Nature produces so lavishly, and in such charming variety of form and colour; but, in addition to their own proper florescence, the plants of woodland, meadow, moor, or down have other "blossoms" that arise from them, although they are not of them. These are the beautiful winged creatures called butterflies, which as crawling caterpillars obtain their nourishment from plant leafage, and in the perfect state help the bees to rifle the flowers of their sweets, and at the same time assist in the work of fertilization.

It is the story of these aërial flowers that we wish to tell, and hope that in the telling we may win from the reader a loving interest in some of the most attractively interesting of Nature's children.

There are many people, no doubt, who take an intelligent interest in the various forms of animal life, and yet do not care to collect specimens because, as in the case of butterflies for instance, the necessity arises for killing their captives. Such lovers of Nature are quite satisfied to know the names of the species, and to learn something of their life-histories and habits. [Pg vi]Still, however, there are others, and possibly a larger number, who will desire to capture a few specimens of each kind of butterfly for closer examination and study. It is believed that this little volume will be found useful to both sections of naturalists alike.

The author in preparing the book has been largely guided by a recollection of the kind of information he sought when he himself was a beginner, now some forty odd years ago.

In conclusion, he desires to tender his most sincere thanks to the undermentioned gentlemen, who so kindly furnished him with eggs, caterpillars, and chrysalids; or favoured him with the loan of some of their choicest varieties of butterflies for figuring; without their valued assistance many of the illustrations could not have been prepared:—Rev. Gilbert Raynor, Major Robertson, Messrs. F. Noad Clark, T. Dewhurst, C.H. Forsythe, F.W. Frohawk, A.H. Hamm, A. Harrison, H. Main, A.M. Montgomery, E.D. Morgan, G.B. Oliver, J. Ovenden, G. Randell, A.L. Rayward, E.J. Salisbury, A.H. Shepherd, F.A. Small, L.D. Symington, A.E. Tonge, B. Weddell, F.G. Whittle, and H. Wood.

Varieties—Messrs. R. Adkin, J.A. Clark, F.W. Frohawk, and E. Sabine.

With kind permission of the Ray Society, figures of the following larvæ and pupæ have been reproduced from Buckler's "Larvæ of British Butterflies":—P. daplidice, C. edusa, M. athalia, P. c-album, S. semele, A. hyperanthus, C. typhon, C. pamphilus, C. rubi, C. argiolus, A. thaumas, A. actæon. Larva only—L. sinapis, A. selene, A. aurinia, and T. pruni.

Figures of A. cratægi, A. lineola, and C. palæmon have been made from preserved skins.

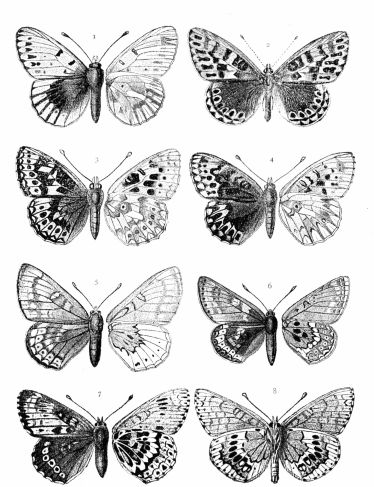

For coloured plates, 1, 30, 42, 48, 58, 66, 98, 100, 112, 116, 118, and the accurately drawn black-and-white figures, including enlargements, the author is greatly indebted to Mr. Horace Knight.

Butterflies belong to the great Order of insects called Lepidoptera (Greek lepis, a scale, and pteron, a wing), that is, insects whose wings are covered with minute structures termed scales. Moths (Heterocera) also belong to the same order, and the first point to deal with is how may butterflies be distinguished from moths? In a broad kind of way they may be recognized by their horns (antennæ), which are slender as regards the shaft, but are gradually or abruptly clubbed at the extremity. For this reason they were designated Rhopalocera, or "club horned," the Heterocera being supposed to have horns of various kinds other than clubbed. As a matter of fact this method of separating moths and butterflies does not hold good in dealing with the Lepidoptera of the world, and it is from a study of these, as a whole, that systematists have arrived at the conclusion that there is no actual line of division between moths and butterflies. In modern classification, then, butterflies are reduced from the rank of a sub-order, which they formerly held, and are now dovetailed into the various newer systems of arrangement between certain families of moths.

As regards British butterflies, however, it will be found that these may be known, as such, by their clubbed horns. Only the Burnets among British moths have horns in any way similar, and these are thickened gradually towards the extremity rather [Pg viii]than clubbed. Day-flying moths, especially the bright-coloured ones, might be mistaken for butterflies by the uninitiated, but in all these the horns will be found not at all butterfly-like.

Although varieties of the species will be referred to in the descriptive portion of the book, a few general remarks on variation in butterflies may here be made. All kinds are liable to vary in tint or in the markings, sometimes in both. Such variation, in the more or less constant species especially, is perhaps only trivial and therefore hardly attracts attention. In a good many kinds variation is often of a very pronounced character, and is then almost certain to obtain notice. Except in a few instances, where the aberration is of an unusual kind, it is possible to obtain all the intermediate stages, or gradations, between the ordinary form of a species and its most extreme variety. A series of such connecting links in the variation of a species is of greater interest, and higher educational value, than one in which the extremes alone have a place.

In those kinds of butterflies that attain the perfect state twice in the year, the individuals composing the first flight are somewhat different in marking from those of the second flight. Such species as the large and small whites exhibit this kind of variation, which is termed seasonal dimorphism. The males of some species, as for example the Common Blue and the Orange-tip, differ from the females in colour; this is known as sexual dimorphism. The Silver-Washed Fritillary, which has two forms of the female, one brown like the male, the other green or greenish in colour, is a good example of dimorphism confined to one sex. Gynandrous specimens, sometimes called "Hermaphrodites," are those which exhibit both male and female coloration, or other wing characters; when one side is entirely male and the other side entirely female, the gynandromorphism would be described as complete.

The ornamentation on the under side of a butterfly differs from that of the upper side, and is found to assimilate or [Pg ix]harmonize in a remarkable manner with the usual resting-place. It is therefore of service to the insect when settled with wings erect over the back, in the manner of all butterflies, except some few kinds of Skippers.

The number of known species of butterflies throughout the world has been put at about thirteen thousand, and it has been suggested by Dr. Sharp that there may be nearly twice as many still awaiting discovery. Dr. Staudinger in his "Catalog" gives a list of over seven hundred kinds of butterflies as occurring in the whole of the Palæarctic Region. This zoological region embraces Europe, including the British Islands, Africa north of the Atlas range of mountains, and temperate Asia, including Japan. The entire number of species that can by any means be regarded as British does not exceed sixty-eight. Even this limited total comprises sundry migratory butterflies, such as the Clouded Yellows, the Painted Lady, the Red Admiral, the Camberwell Beauty, and the Milkweed Butterfly; and also the still less frequent, or perhaps more accidental visitors, the Long-tailed Blue and the Bath White. Again, the Large Copper is now extinct in England, and the Mazarine Blue does not seem to have been observed in any of its old haunts in the country for over forty years. The Black-veined White is also scarce and exceedingly local.

The majority of the remaining fifty-seven butterflies may be considered natives, and of these about half are so widely distributed that the young collector should, if fairly energetic, secure nearly all of them during his first campaign. The other species will have to be looked for in their special localities, but a few kinds are so strictly attached to particular spots, that a good deal of patience will have to be exercised before a chance may occur of obtaining them.

A few remarks may here be made in reference to the names and arrangement adopted in the present volume.

As will be adverted to in the descriptive section, the English [Pg x]names of our butterflies have not always been quite the same as those now in general use. There has, however, been far less stability in scientific nomenclature, and very many changes in both generic and specific names have been made during the past twenty years, more especially perhaps within the last decade.

Genera are now founded by some specialists on characters which formerly served to distinguish one species from another, whilst other authorities merge several genera in one upon certain details of structure that are common to them all.

Patient research into the entomological antiquities has revealed much important material, some of which may furnish a new interpretation of the Linnean classification of Lepidoptera.

The discovery of the earliest Latin specific name bestowed upon an insect, is a labour which entails a large expenditure of time and requires fine judgment. Great credit is therefore due to those who undertake such investigations, the result of which may tend to the establishment of a fixed nomenclature in the, probably not remote, future, although it sadly hampers and perplexes students in the meanwhile.

All things considered then, it has been deemed advisable not to make many changes in specific names, and to retain the old genera as far as possible. The arrangement of families, genera, etc., will be found to accord with that most generally accepted both in England and on the continent.

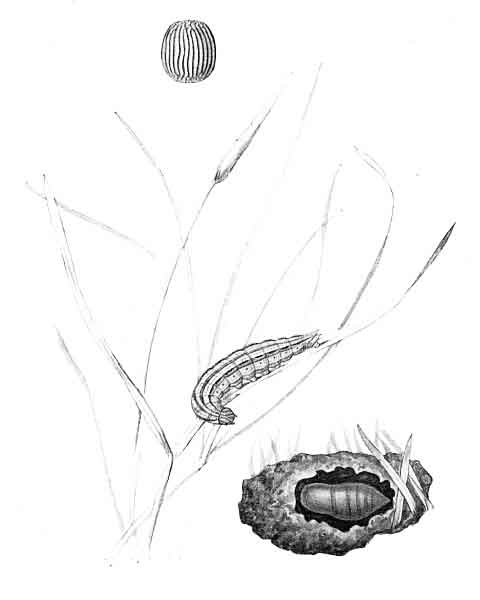

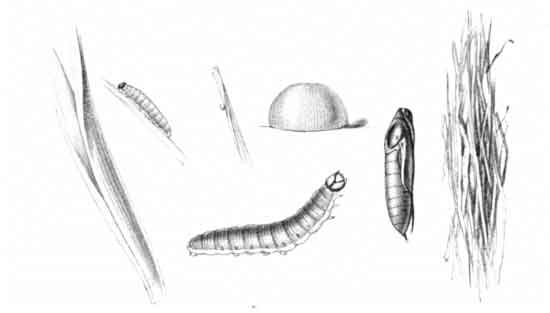

As is the case with all other Lepidoptera, butterflies pass through three very distinct stages before they attain the perfect form. These stages are:—1. The egg (ovum, plural ova). 2. The caterpillar (larva, larvæ). 3. The chrysalis (pupa, pupæ). The perfect insect is called the imago (plural imagines).

Butterfly eggs are of various forms, and whilst in some kinds the egg-shell (chorion) is elaborately ribbed or fluted, others are simply pitted or covered with a kind of network or reticulation; others, again, are almost or quite smooth. If the top of an egg, such as that of the Purple Emperor (Plate 28), is examined under a good lens a depression will be noted, and in this will be seen a neat and starlike kind of ornamentation. In the middle of this "rosette" are, present in all eggs, minute apertures known as micropyles (little doors), and it is through these that the spermatozoa of the male finds entry to the interior of the egg and fertilization is effected. The changes that occur in the egg after it is laid are of a very complex nature, and readers [Pg 2]who may desire information on this subject are referred to Sharp's "Insects," Part I., in the "Cambridge Natural History," where also will be found much interesting and instructive matter connected with the caterpillar and chrysalis, to which stages only brief reference can here be made.

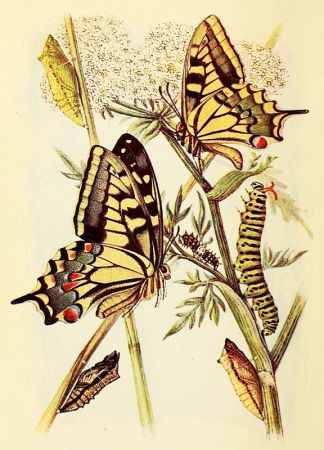

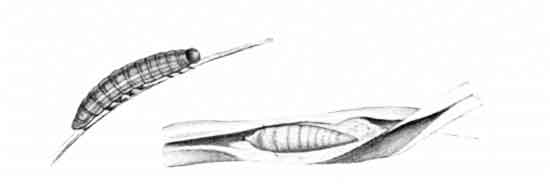

The second stage is that of the caterpillar, and in some species, such as the Red Admiral, this is of very short duration, a few weeks only, whilst in others, as for example the Small Blue, it usually lasts for many months. There is considerable diversity both in the shape and, where it is present, in the hairy or spiny clothing (armature) of caterpillars. All, however, are alike in one respect, that is the body is divided into thirteen more or less well-defined rings (segments), which together with the head make up fourteen divisions. In referring to these body-rings, the first three nearest the head, each of which is furnished with a pair of true legs (thoracic legs), are called the thoracic segments, as they correspond to the thorax of the perfect butterfly. The remaining ten rings are the abdominal segments; the last two are not always easily separable one from the other, and so for all practical purposes they may be considered only nine in number. These nine rings, then, correspond to the abdomen of the future butterfly. The third to sixth of this series have each a pair of false legs (prolegs), and there is also a pair on the last ring; the latter are the anal claspers.

The warts (tubercles) are the bases of hairs and spines, and are to be seen in most butterfly caterpillars, but they generally require a lens to bring them clearly into view. These warts are usually arranged in two rows on the back (dorsal series) and three rows on each side (lateral series).

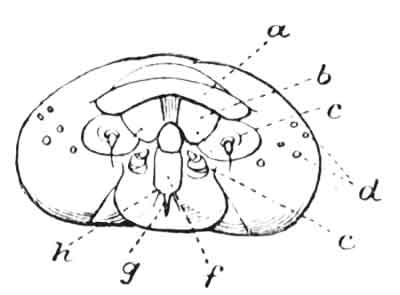

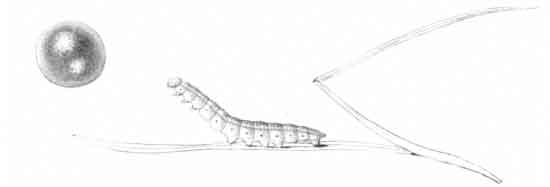

Fig. 1.

Young caterpillar of Orange-tip highly magnified.

(After Sharp.)

All the various parts referred to, or to be presently mentioned, may be seen in Fig. 1, which also shows a peculiarity that is [Pg 3]found in very young caterpillars of the Orange-tip, and in some others of the "Whites" (Pieridæ). The odd thing about this baby caterpillar is that the fine hair arising from each wart is forked at the tip (Fig. 1, a), and holds thereon a minute globule of fluid. When the caterpillars become about half grown these special hairs are lost in a general clothing of fine hair. Fig. 1, b, represents a magnified single ring of the caterpillar, and this shows a spiracle and the folds of the skin (subsegments). The manner in which such folding occurs is to be observed in the higher study of larval morphology.

On each ring, except the second (including now the three thoracic with the nine abdominal; and so making twelve rings), the third, and the last, there is an oval or roundish mark which indicates the position of the breathing hole (spiracle). Through these minute openings air enters to the breathing tubes (tracheæ), which are spread throughout the interior of the caterpillar in a seemingly complicated kind of network of main branches and finer twigs; air is thus conveyed to every part of the body. In the event of one or two air-holes becoming in any way obstructed, the caterpillar would possibly be none the worse; but if all the openings were closed up effectually, it would almost certainly die. Total immersion in water, even for some hours, is not always fatal.

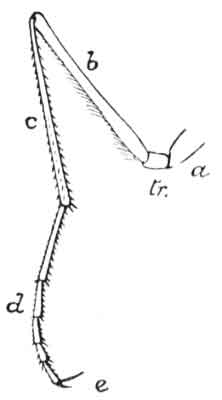

Turning again to the "feet" of the caterpillar, it will be seen [Pg 4]from the figure that the true legs (a) differ from the false legs (b) in structure. The former are horny, jointed, and have terminal claws; the latter are fleshy, with sliding joints, and the foot is furnished with a series of minute hooks which enable the caterpillar to obtain a secure hold when feeding, etc. The false legs are also the chief means of locomotion, as the true legs are of little service for this purpose. The true legs, however, appear to be of use when the caterpillar is feeding, as the leaf is held between them so as to keep it steady whilst the jaws are doing their work.

Fig. 2.

(a) True and (b) false legs.

In the accompanying figure of the head of a caterpillar the mouth parts are clearly shown. The biting jaws (mandibles) are slightly apart, above them is seen the upper lip (labrum), and below them is the under lip (labium or lingua). The maxillæ are very tiny affairs, but they should be noted because in the butterfly they become the basal portions of the two tubes which, when united together, form the sucking organs (proboscis). The eyes, or ocelli as they are termed, are minute, and are said to be of slight use to the caterpillar as organs of sight, so that it probably has to depend on its little feelers (antennæ) for guidance to the right plants for its nourishment. Attention should also be given to the spinneret, as it is by means of this that the silken threads, etc., for its various requirements are provided; the substance itself being secreted in glands placed [Pg 5]in the body of the caterpillar. The palpi are organs of touch, and seem to be of use to the caterpillar when moving about.

Fig. 3.

a, labrum; b, mandible; c, antenna; d, ocelli; e, maxilla;

f, labium; g, spinneret; h, labial palp.

Immediately after hatching, many caterpillars eat the egg-shell for their first meal; they then settle down to the business of feeding and growing. It should be remembered that it is entirely on growth made whilst in the caterpillar stage that the size of a butterfly depends. In the course of a day or two the necessity arises for fasting, as moulting, an important event, is about to take place. Having spun a slender carpet of silk on a leaf or twig, the caterpillar secures itself thereto, and then awaits the moment when all is ready for the transformation to commence. After a series of twistings from side to side and other contortions, the skin yields along the back near the head, the head is drawn away from its old covering and thrust through the slit in the back, the old skin then peels downwards whilst the caterpillar draws itself upwards until it is free. The new skin, together with any hairs or spines with which it may be clothed, is at first very soft. In the course of a short time all is perfected, and the caterpillar is ready to enter upon its second stage of growth. At the end of the second stage the skin-changing operation is again performed, and the whole business is repeated two or more times afterwards. Finally, however, when the caterpillar has shed its skin for the last time, the chrysalis is revealed, but with the future wings seemingly free. These, together with the other organs, are soon fixed down to the body by the shell, which results from a varnish-like ooze which covers all the parts and then hardens.

Generally speaking, newly hatched caterpillars, though of different kinds, are in certain respects somewhat alike, but the special characters of each begin to appear, as a rule, after the first change of skin (ecdysis), and these go on developing with each successive stage (stadium) until the caterpillar is full grown. The form assumed in each stage is termed the instar, therefore a caterpillar just from the egg would be referred to as [Pg 6]in the first instar; between the first and second changes of skin, as in the second instar, and so on to the chrysalis, which in the case of a caterpillar that moulted, or changed its skin, four times before attaining full growth, would be the sixth instar, and the butterfly would then be the seventh instar. In practice, however, it is usually the stages of the caterpillar alone that are indicated in this way.

The term chrysalis more especially applies to such of them as are spotted or splashed with metallic colour, as, for example, the chrysalids of some of the Fritillaries. The scientific term for the chrysalis is pupa, which in the Latin tongue means "a doll or puppet."

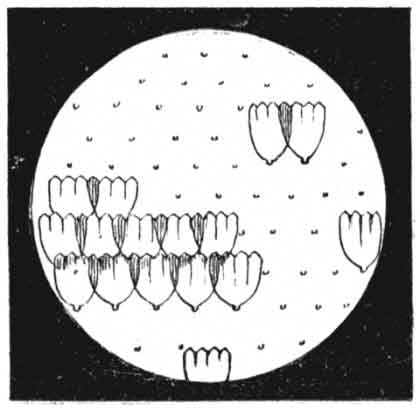

Fig. 4.

Caterpillar of Small White, about to change to chrysalis.

In passing to the chrysalis stage the caterpillars have sometimes to make rather more preparations than in previous skin-changing provisions. Those of the Swallow-tail, Whites, Orange-tip, and similar kinds have to provide a silken girdle for the waist as well as a pad for the tail. Chrysalids that hang suspended, head downwards, such as the Vanessids, Fritillaries, etc., are attached by the cremaster—a hooked arrangement on the tail (Fig. 5)—to a pad of silk; others, such as the Blues and the Coppers, appear to be held in position on a leaf, or some other object, by means of a fine girdle of silk, or sometimes a few silken threads spread net-like above and below them—rudiments of a cocoon in fact. Chrysalids of the Skippers are enclosed in a more or less complete cocoon placed within a chamber, formed of a leaf or leaves of the food-plant, drawn together by silken cables. Some of these [Pg 7]chrysalids are furnished with hooks on the tail as well as with a girdle for suspension; but others have hooks only.

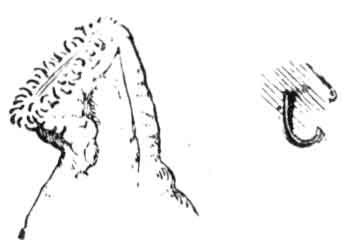

Fig. 5.

Enlarged view of cremaster,

and a hook still more enlarged.

(After Sharp.)

As almost all the chrysalids here considered are figured in the illustrations, it will be unnecessary to refer in detail to their great diversity in form, but a few general remarks on the structure of a chrysalis may be made.

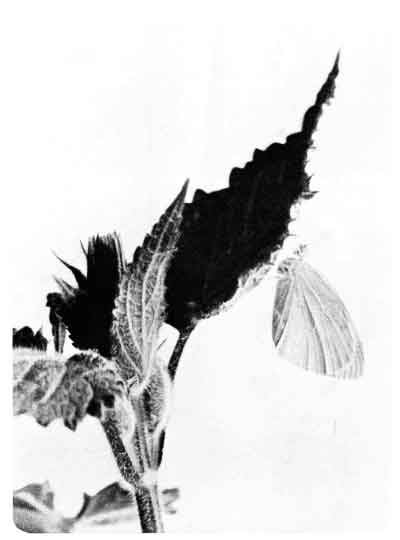

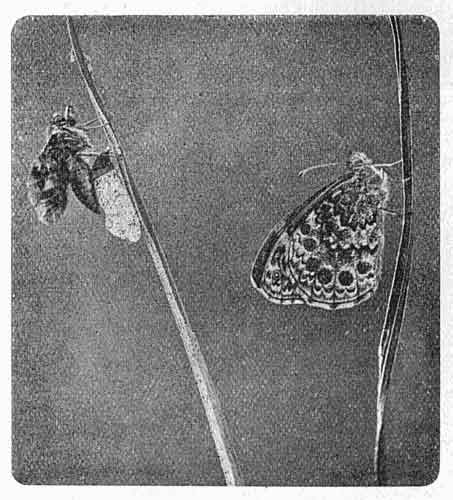

If the upper (dorsal) surface of a chrysalis is examined, the thorax and the body divisions will easily be made out, while, by looking at the sides and the under (ventral) surface, the various organs, such as the wings, legs, antennæ, etc., will be found neatly laid along each side of the "tongue," or proboscis, which latter extends down the centre. All these are separately encased, but by reason of the shell mentioned in the remarks on the caterpillar, they appear to be welded together. When, however, the butterfly is ready to emerge, the shell of the chrysalis is split along the thorax and at the lower edge of the wing-cases, and the insect is then able to release itself from the pupal trappings. This breaking open of the chrysalis shell is termed dehiscence (dehisco, "to split open"), and the manner in which it is effected varies in different species. The emergence of a butterfly from the chrysalis is always an interesting operation to observe, and every one should make a point of watching the process, so that he may obtain practical knowledge of how the thing is done. A photograph of it will be found in the description of the Wall Butterfly.

Having safely cleared itself free of the chrysalis shell, the butterfly makes its way to some suitable twig, spray, or other object, from which it can hang, sometimes in an inverted position, [Pg 8]whilst a very important function takes place. This is the distention and drying of the wings, which at first are very weak and somewhat baggy affairs, although the colour and markings appear upon them in miniature. All other parts of the butterfly seem fully formed, but the helpless condition of the wings alone prevent it as yet from floating off into the air. In a remarkably short time, after the insect has settled to the business, the fluids from the body commence to flow and circulate through the wings, and these are seen gradually expanding and filling out until they attain their proper size. Occasionally there is some obstruction to the equal distribution of the fluids, and when this occurs a greater or lesser amount of distortion, or cockle, in the wing affected is the result. When the inflation is completed the wings are kept straight out for a time; they are then motionless, but all their surfaces are well apart. The wings being now fully developed, the further flow of fluid appears to be arrested. It has been stated by some authorities that this fluid is fibrin held in solution, and that when the work of expansion has been accomplished, the watery medium evaporates, leaving the fibrin to harden, and so fasten together the upper and lower membranes of the wing and to fix the veins, or nerves, in their proper position. Mayer, a specialist on these matters, referring to the expansion of the wings, remarks that the blood [the fluid previously mentioned] forced into the freshly emerged wing would cause it to become a balloon-shaped bag if it were not for fibres that hold the upper and lower walls closely together. The fibres referred to, he states, are derived from those hypodermic cells which do not contribute to the formation of scales, but are stretched out from one wall of the wing to the other.

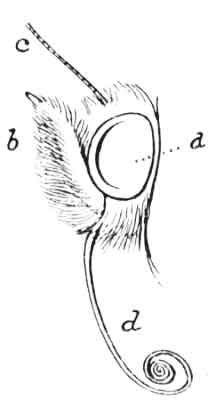

Fig. 6.

Head of Butterfly.

a, compound eye; b, palp; c, antenna; d, proboscis.

It may be well now to briefly consider some of the structural details of the perfect butterfly, so a beginning will be made with the head (Fig. 6). When looking at the head of a butterfly, the first thing to attract the attention is the very large size [Pg 9]of the compound eye (a), which seems to take up the largest share of the whole affair. Although so bulky and so complex in the matter of divisions, or facets, as they are termed (the facets are not shown in figure), the power of sight is not really very keen. A butterfly can see things in a general way readily enough, but it seems unable to clearly distinguish one object from another. When engaged in egg-laying, the female butterfly rarely fails to place her eggs on a leaf or spray of the plant that the future caterpillar will feed upon, and it has been suggested that in making this unerring selection the insect is guided more by the sense of smell than by that of sight.

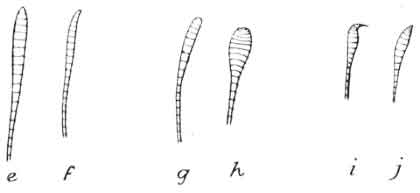

The horns (c) (antennæ), or feelers, as they are sometimes called, which adorn the head, are now considered to be organs of smell. These are composed of a number of rings or segments, which vary in the different kinds of butterfly, as also does the shape of the terminal rings forming what is known as the club. In Fig. 7, e (Purple Emperor) and f (Marbled White) represent the gradually thickened club; in g (Brimstone) and h (Dark-green Fritillary) the clubs are more or less abruptly formed. Our Skippers have well-developed clubs; these may be hooked at the tip as in i (Large Skipper), or blunt at the tip as in j (Chequered Skipper); at the base of the Skipper's antenna, that is at the point where it is inserted in the head, there is a tuft of rather long hairs.

Of the various mouth parts it will only be necessary to refer to the suction-tube, Fig. 6, d (proboscis), often called the "tongue," which is perhaps the most important, at least to the butterfly itself, as this organ is, in a way, as useful to it in the perfect state [Pg 10]as were the very differently constructed strong biting jaws (mandibles) of its caterpillar existence. These latter in the butterfly are only microscopically represented, and the suction-tube of the perfect insect is an extension of the maxillæ, which in the caterpillar are not conspicuous. When not engaged in probing the nectaries of flowers for the sweets they contain, the suction-tube is neatly coiled up between the palpi (Fig. 6, b). Its great flexibility is due to the many rings of which it is composed. Although seemingly entire, it is really made up of two tubes, each being grooved on its inner side, and forming, when the edges are brought together, an additional central canal, through which the sweets from the flowers and other liquids are drawn up into a bulb-like receptacle in the head, whence it passes into the stomach. When it is remembered that the passage of sweet, and no doubt sticky, fluid through the central tube would most probably result in its walls becoming clogged, there is reason to suppose that the method of construction permits of the canal being cleansed from time to time.

Fig. 7.

Antennæ of Butterflies.

Fig. 8.

Leg of Butterfly.

The important divisions of the body are the thorax and the abdomen. The former is made up of three segments (named the pro-, meso-, and meta-thorax), each of which, as in the caterpillar state, is furnished with a pair of legs; the second and [Pg 11]third, which are closely united, each bear a pair of wings also. The legs, which in the butterfly are adapted for walking at a leisurely pace, are made up of four main parts; these are (a) the basal joint (coxa, coxæ), (b) the thigh (femur, femora), (c) the shank (tibia, tibiæ), and (d) the foot (tarsus, tarsi). The small joint uniting the coxa with the femur is the trochanter (tr.). The foot usually has five joints, the last of which is provided with claws (e). The abdomen really consists of ten rings or segments according to some specialists. Examined from above, the female butterfly appears to have only seven rings and the male butterfly eight. This discrepancy arises from the fact that in the former sex two rings and in the latter one ring are withdrawn into the body, and so are tucked away out of sight. The organs of reproduction are placed in the terminal ring. The breathing arrangements are pretty much as in the caterpillar, but the external openings are not so apparent owing to the dense clothing of the body.

The beauty of a butterfly's wings is intimately connected with the form and colour of the scales with which they are covered, as with a kind of mosaic; but before the scales and their method of attachment, etc., are referred to, something should be said about the wings themselves. The various shapes of these organs of flight will be seen on turning to the plates, where will be found accurate portraits of every species that will be dealt with in the descriptive section later on.

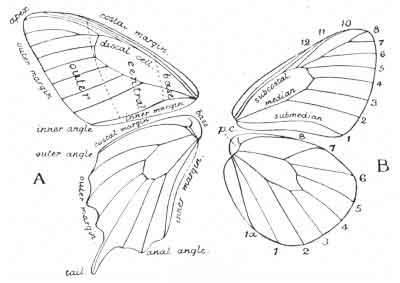

A butterfly's wing consists of an upper and a lower membrane, with a framework of hollow tubes, acting as ribs, between the two layers. Fig. 9, A, shows a fore and a hind wing of the [Pg 12]Swallow-tail butterfly. The point of attachment with the thorax is the base of the wing, and the edge farthest from the base is the outer margin (termen); the upper edge, or front margin, is the costa; and the lower edge is the inner margin (dorsum). The point where the upper margin meets the outer margin on the fore wing is the apex, but on the hind wing it is called the outer angle; the angle formed by the junction of outer and inner margins is the inner angle of the fore wing, but the anal angle of the hind wing. The term tornus is sometimes used for this angle on either wing. Dividing the wings transversely into three portions, we have three areas, termed respectively basal, central or discal, and outer. These are terms used in descriptions of butterflies, and it will be useful to remember them.

Fig. 9.

Butterflies' Wings.

The ribs of a butterfly's wings are by some authors described as veins, whilst others style the main ones nervures, and the branches nervules. Fig. 9, B, represents the venation, or neuration of the Black-veined White, and the numeral system [Pg 13]of indicating the veins has been adopted, as it is the most simple. In another method of referring to the venation, and one that has been much in use, vein 12 of the fore wing would be styled the costal nervure, or vein; veins 11, 10, 9 (absent in figure), 8, and 7 would be the subcostal nervules 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5; 6 would become the upper radial, and 5 the lower radial; 2, 3, and 4 would be the median nervules 1, 2, and 3; vein 1 would be the submedian nervure, or vein. On the hind wing, vein 1a would be the internal vein; 1 the submedian; 2, 3, and 4 the median nervules; 5 the lower and 6 the upper radials; 7 the subcostal, and 8 the costal nervures. Just near the base of the hind wing will be noted a short recurved vein (p.c.); this is the precostal vein, and so named because it comes before the costal. It is always absent in some species. Comparing the venation of A and B, it will be seen that in A the fore wing has 12 veins and the hind wing 8 veins, whilst in B there are only 11 veins on the fore wing, but the hind wing has one vein more than that of A. In the Black-veined White, vein 9 is absent on the fore wing, and on the hind wing there is one internal vein.

Fig. 10.

Arrangement of Scales.

(After Holland.)

Dust-like as they appear to the naked eye, the scales from a butterfly's wing seen under the microscope are found to be exceedingly interesting structures and very varied in shape. Dr. Sharp describes them as "delicate chitinous bags." Chitin, it may be mentioned, is [Pg 14] the horny substance of which the chrysalis shell is formed, and this was adverted to when discussing the chrysalis stage as a varnish-like ooze. As seen on the wings, the scales are flattened and the upper and under sides are then almost, or quite, brought together. They are attached in lines on the membrane or covering of the wing by short stalks which fit into sockets in the membrane. The arrangement of the scales, which has often been stated to resemble that of the slates on a roof, is shown in Fig. 10.

Colour is chiefly due to pigment contained in the scale or adhering to the interior of its upper side. Pigments, according to Mayer, are derived, by various chemical processes, from the blood while the butterfly is still in the chrysalis. Some scales have minute parallel lines (striæ) on their upper sides, and rays of light falling on these are turned aside or broken up, and so produce changes in the colouring of a wing, according to the angle from which it is looked at.

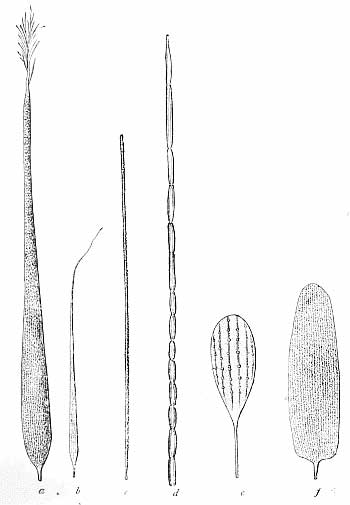

The males of many kinds of butterfly have special scales, which are known as androconia, or plumules. It is believed that these are scent organs. Whatever their particular use may be to the possessor, these androconia enable the entomologist to distinguish male specimens from females with great certainty. In the Fritillaries they are placed on one or more of the median nervules (veins 2, 3, and 4) of the fore wing. In the Meadow Brown and its kindred they form brands on the disc of the fore wing. In the Skippers they are placed in a fold of the costa in some species, and in other species they are clustered together, into more or less bar-like marks, about the middle of the fore wings. Some of these various shaped "plumules" are shown in the illustrations.

Fig. 11.

Butterfly Plumules.

a. Tufted Plumule (Satyrs);

b. Bristle Plumule (Grizzled Skipper);

c. Hair Plumule (Dingy Skipper);

d. Jointed Plumule (Silver-studded Skipper);

e. Bladder Plumule (Common Blue);

f. Dotted Plumule (White-letter Hairstreak).

(After Aurivillius.)

In the foregoing sketch of the life cycle of a butterfly, the object has been to condense as much necessary information as possible into a limited space. Many matters of importance to the student have not been touched on, but it was considered [Pg 16]that, as these were more especially connected with a higher scientific phase of the subject than would here be found helpful, they might be omitted.

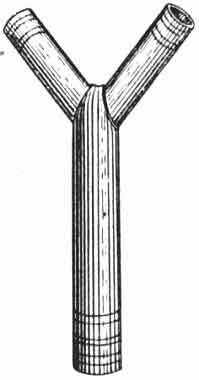

Fig. 12.

Y-piece

Naturally the first matter for consideration, when the formation of a collection of butterflies has been decided upon, is how to set about it. Well, there are two methods of effecting our purpose. The specimens may be purchased from a dealer in such things, or we may acquire an outfit comprising net, boxes, and pins, and go in search of the insects ourselves. Apart from its healthful and entertaining possibilities, the latter method has very much to recommend it. In the first place, those who are at all observant—and no true lover of Nature can be suspected of being otherwise—will become acquainted with the objects under natural conditions, and so be enabled to appreciate them more highly than could be the case if they were obtained in any other way. The chief purpose in making a collection of Natural History specimens should be study of some kind rather than mere accumulation.

The net may be a simple cane ring one of home construction, or the more elaborate, but not necessarily more efficient, fabrication of steel-jointed ring with grenadine bag and telescopic handle. A good serviceable butterfly-net may be fitted up as follows. Procure a light flexible cane, about 3 feet or so in length. Next, a Y-shaped holder (Fig. 12) for the two ends of the cane will have to be made, and either tin or brass may be used for the purpose. The latter is the better metal, and the [Pg 17]parts should be brazed and not soldered together. (If difficulty is experienced in the manufacture of this article, it may be obtained from any dealer in entomological requisites for a few pence.) The bag may be made of leno, tarletan, or fine mosquito netting; the latter is the most serviceable, and should be used wherever it can be obtained. The size of the bag at the top, where it has a wide band to take the cane, should not exceed the circumference of the cane ring when fitted in the two arms of the Y-piece; the depth should be just a little less than the length of one's arm, and the bottom should be rounded off so that no corners are available for the butterflies to get into and damage their wings. An opening about 3 inches in length is left in the seam of the bag just under the Y-piece, so that the cane may be removed and rolled up when the net is put out of action. The ring band should be covered with some stouter material to prevent it from fraying, thin leather is sometimes used for this purpose; the slit in the seam also requires protecting on each side, and strengthening at the lower end by a crosspiece. An ordinary walking-stick, with the ferrule end thrust into the longer tube of the Y, will serve as a handle to the complete net.

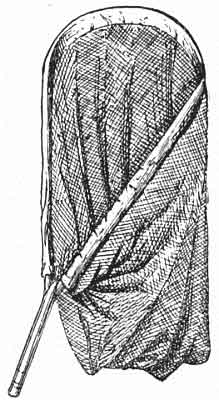

Fig. 13.

Kite or Balloon Net.

The dealers adverted to above generally stock a variety of nets ready fitted for use. Among these is a very useful pattern known as the kite or balloon net (Fig. 13). This is made in two sizes, and as the writer has used this kind of net for at least [Pg 18]twenty years, he is able to speak well of its merits. It does not need a stick for ordinary work, and the long end of the socket should be about 9 inches in length.

The "ring" being made of four separate rods, in addition to the Y-piece, some care will have to be taken when a balloon net is unshipped. It will be found a good plan to leave the two short curved canes in the hem or band of the bag, remove the two straight arms from the Y-piece and the band, place these on top of the bag when folded, and then roll all up together. A canvas or linen pouch or pocket, opening at one end, may be made to contain the whole affair.

The umbrella-net, when in its case, looks very like the familiar "gamp." Its chief merit is that it is quickly put up for use, and its principal defect is that the stick, which crosses the mouth of the bag, frequently damages the quarry.

Another implement of the chase known as the "Ortner" net is used pretty extensively on the Continent. English entomologists who have used it speak of it most favourably. Its great advantage over other nets is found in the simple and rapid method of its adjustment for use.

In connection with nets it may be well to advise the wielder to remember that carrying a threaded needle is a useful practice. Tears and rents are apt to occur, and it is well to have the means of repair handy.

Some collectors seem to be expert at killing butterflies by pressing the sides of the thorax together. The method is not, however, as satisfactory as one could wish, and so no more need be said about it. For the happy despatch of insects, the cyanide bottle is frequently used. All that has to be done is to clap the open bottle over the captive while still in the net, then draw the gauze or what-not over the mouth of the bottle until the bung can be inserted, and the whole affair withdrawn from the net.

Cyanide of potassium is a deadly poison, and no inexperienced [Pg 19]person should attempt to charge a cyanide bottle himself. In fact, chemists are not permitted to supply the poison to unknown customers. Under certain conditions, however, a chemist might consent to make up a killing bottle, and the following instructions may help him in doing this. A fairly strong, clear glass bottle, holding about 4 to 6 ounces; the mouth must be pretty wide, and closed with a well-fitting bung that has been dipped in melted wax; if the bung is of fine grained cork, the wax will not be needed. At the bottom of the bottle place a thick layer of the cyanide, and over this pour plaster of Paris which has been mixed with water and converted into a cream-like paste: one-third of the depth of the bottle to be occupied by the poison and plaster, but only a thin layer of the latter should cover the former.

Dealers who supply cyanide bottles (uncharged) also have in stock a brass bottle for chloroform, which some people prefer as a killing agent because it does not change the colour of insects as cyanide is occasionally apt to do. In using this, the insect should be boxed, then a drop of the chloroform may be allowed to run from the bottle over the perforated lid or bottom of the box, and a finger put over the hole or holes for a short time.

The majority of butterflies, if transferred to pill boxes from the net, settle down quietly. In this way they may be taken to one's home and there placed, boxes and all, into the ammonia jar, a simple but very effective contrivance. To start one of these lethal chambers, procure a good sized pickle jar, one of the brown earthenware kind, holding about 2 gallons. At the bottom put in several layers of stout blotting-paper, and have ready a covering for the mouth of the jar. This covering may be of skin, waterproof-apron material, or even thick brown paper. Before turning the boxes into the jar, lift up the blotting-paper, drop in about half a teaspoonful of strong liquid ammonia (⋅880) and replace blotting-paper. Directly the boxes are in the jar, [Pg 20]put on cover and tie it down securely. If brown paper is used, a piece of pasteboard should be put over it and a weight on top of that. Suffocation takes place directly the gas reaches the insect, but it often happens that one or more of the boxes exclude the gas longer than others. At the end of half an hour all may be removed, but the insects will not hurt in any way if left in all night.

The best kind of boxes for field work are those known as "glass bottomed," as in these the captives can be examined and, if not wanted, may be set free. It is always better to retain only those specimens that we know are really useful, rather than to incur the necessity of throwing away insects after we have deprived them of life.

If butterflies are pinned on the spot, a collecting box will be required, and the most useful and convenient is one of an oval shape. This should be made of zinc, and lined with cork that is held in place by zinc clips. The cork should be kept damp when in use, and the water used for damping should have a few drops of carbolic acid mixed with it so as to prevent the formation of mould. Insects may remain in such a box for several days without injury. This box will also be useful for relaxing specimens that have been badly set, or have been simply pinned during the busy season.

In the matter of pins, it is not altogether easy to make suggestions. There are, perhaps, only two makers in this country of entomological pins, and each of these supplies a large number of sizes. The selection of suitable pins will largely depend on the method of setting adopted. Black pins are, however, the best for butterflies, and are now used almost exclusively.

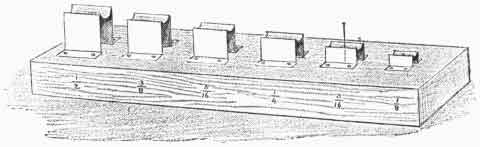

In pinning a specimen care should be taken that the pin passes in a direct line through the centre of the thorax. Insects that are properly pinned set better, and have a neat appearance when arranged in the collection. For regulating the [Pg 21]height of specimens on the pin, a handy graduated stage has been devised by Dr. Scarancke (see Fig. 14). Each of the little rests are hollowed to receive the body of the insect, so suppose we wish a quarter of an inch of the pin to show below the body of a specimen, the pin is pushed through a perforation in the centre of the rest groove marked "3/16" until the point touches the wooden base, and we have the required length.

Beginners would, perhaps, find three sizes of pins quite sufficient for almost every purpose—say, Nos. 10, 8, and 5 of one maker; or Nos. 9, 17, and 5 of the other. In each case the first size pin would be suitable for small butterflies, the second size for all other butterflies except quite the largest, for which No. 5 would remain. English pins are sold by the ounce.

Fig. 14.

Pinning Stage.

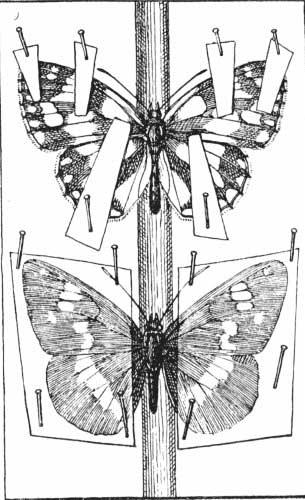

Setting, as it is called, that is, spreading out and fixing the wings so that all their parts are displayed, arranging the horns, etc., is perhaps the most tedious work that the collector will be called upon to perform. The various methods will be referred to, and he must then decide as to which he will adopt. Each style may possibly be found to have its difficulties at first; but time and patience will overcome these, therefore he must be prepared for a good deal of troublesome practice before he quite gets "the hang of the thing," and can [Pg 22]set out his specimens without removing a greater or lesser number of the scales.

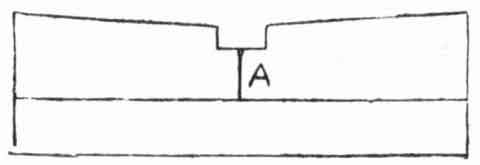

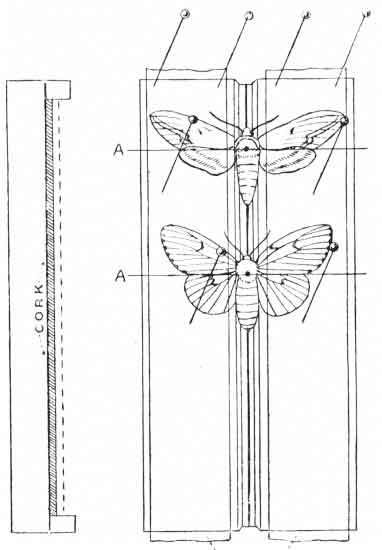

Fig. 15.

Board for Flat-setting.

First, as to the flat and high setting as practised by almost every lepidopterist abroad and by some in our own country. Boards of the pattern, shown in the illustration, will be required; also some tracing cloth, and a pair of entomological forceps, bead-headed pins, etc. In these boards, it will be noticed, the sides tilt outwards; this is to allow for drooping of the wings, which generally occurs after insects are removed from the "sets." In this case the wings would settle dead flat, which is considered to be the acme of perfection in this style of setting. Carlsbad or other foreign pins would be used for this kind of work. They are of a uniform length, about one inch and a half, but vary in thickness, and are usually sold by the 100 or 1000.

Fig. 16. Fig. 17.

Longitudinal Section of Setting-board.Setting-board in use.

Manipulation of the specimen on these boards is as follows. Having carefully pinned it, leaving the greater length of pin below the insect, guide the pin carefully through the narrow opening (a Fig. 15 and the cork (Fig. 16) below to a suitable depth, so that the body of the insect rests in the groove and the wings lie easily on the board. Then take two strips of tracing cloth, glazed side downwards, and pin them on at the end of each side of the setting-board (Fig. 17). The strip should be just wide enough to cover all but the basal part of the wings. Now pass the strips over the wings, press one side lightly with the fingers of the left hand while the wings are moved into position with the setting needle (a fine needle with eye end fixed into the stick of a small penholder will do for this) from the uncovered base, a pin being inserted below the fore wing while the hind wing is brought into position, but when this [Pg 24]has been done and another pin inserted to keep it in place, as shown in the diagram, the first pin may be removed; repeat the same operation on the other side. Other pins will be required to keep the horns, etc., in place. In dealing with the next specimen the strips will have to be turned back while it is fixed into position, then proceed as before. An imaginary line following the inner margin of the fore wings and passing through the pin on the thorax is an excellent guide to uniformity in setting. The groove will prevent the pin leaning to either side, but care should be taken that it does not incline either forwards or backwards. The strip of tracing cloth may be used more than once, but the roughness of the pin holes should be removed by drawing the strip across the back of a knife.

Fig. 18.

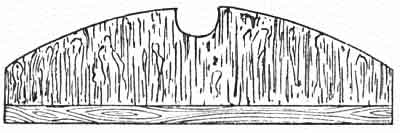

"Saddle" Setting-board.

The setting-boards most frequently used in this country have sloping sides, and are known as saddles (Fig. 18). Where tracing cloth is used, the modus operandi is exactly similar to that just described, but small pins will do for pinning down the strips, as the saddles are made of cork, or cork carpet, instead of wood.

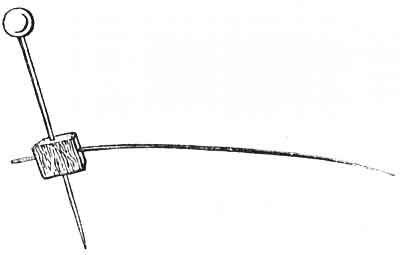

Fig. 19.

Setting-bristle.

The following method of setting butterflies on the English kind of "board" or saddle is frequently adopted. Select a suitable saddle, that is one that has the groove wide enough to take the body, and rather wider than the wings when expanded. A setting bristle [Pg 25]will then be required. This is made, as shown in Fig. 19, by fixing a fairly long and stout bristle, or a very fine needle, or a thin length of quill, in a cube of cork; the cork cube has a stoutish and sharp-pointed pin pushed through it as indicated. Having placed the first insect on the saddle with its body comfortably resting in the groove and the wings flush with the surface, the setting bristle is then brought into action. The point of the pin is rested on the saddle directly in the rear of the hind wing, and the top of the bristle touching the saddle in advance of the front wing. Tilt the pin slightly forward until the bristle presses lightly on the central area of the wings, then with the setting needle push the wings into the required position, and at the same time drive pin of bristle into the saddle. After the wings have been secured by means of braces (triangular pieces of thin card or stout paper, with a pin through the base of the triangle), proceed in the [Pg 26]same way with the other side. Finally, fix a brace to the tip and angle of each fore wing to keep them from turning up in drying, and a pin or two may be required for the horns if these are not in a good position. Instead of using braces, a strip of transparent paper may be pinned over the wings beyond the bristle, but in this case the bristle must be pressed across the wings at a point nearer their base than in the previous method (see lower figure in Fig. 20). In lieu of a setting bristle a length of sewing cotton may be used. Tie a double knot at one end, and through this pass the point of a pin in such a way that the cotton lies flush on the saddle when in use. Insert the pin firmly in the saddle a little in advance of the fore wing, then draw the cotton downwards across the wings and hold it taut, with the fore finger of the left hand placed on it just in rear of the hind wing. Whilst so held the wings can be got into pose with the setting needle, and braces may then be applied as previously directed.

Fig. 20.

Brace and Band Modes of setting.

Fig. 21 shows a specimen set by a method that is in vogue in the north. Blocks of soft pine, grooved and bevelled as in the cork saddle, are easily made. Down the centre of the groove there is a saw cut for the point of the pin to enter, and nicks are cut along the bottom edge at each end. One end of a length of cotton is knotted and fixed in a nick, then a turn is taken over the wings on one side; these are placed in position and secured by other turns of the cotton. The other side is then treated in the same manner, and the end of the cotton fastened off in one of the nicks. This is a quick and, in skilled hands, a very neat method.

As specimens after being set will have to remain on the setting boards or saddles for at least a fortnight, it will be necessary to protect them not only from dust, but from possible attack by ants, cockroaches, mice, etc. This is best ensured by placing the sets into a receptacle called a setting or drying house. Dealers supply these, but the young collector may have a knowledge of carpentry and could make one for himself. The [Pg 27]height and depth of such a construction would depend upon the number and the width of the boards or saddles that would be put therein. The width would be that of the length of the boards, which is usually 14 inches. About a quarter of an inch of cork is cut off each end of the saddles, and grooves are cut in the sides of the house for these to run in. The back and the door should have a square of fine perforated zinc inserted in them for ventilation. As an example of holding capacity it may be well to note that a house with a height of 12 inches, and a depth of 6 inches, inside measurement, would take eighteen 2-inch boards if the grooves were cut at 2 inches apart, or twenty-four boards of same width if 1-1/2 inch only were allowed between the grooves.

Fig. 21.

Cotton Method of setting.

In taking insects off the sets, the braces or strips should be removed from the wings, and the pins from the horns, with care, as a good deal of damage can be done in the performance of this operation, simple as it seems to be. A little twist of a brace and away goes a patch of scales, a side slip of a pin and off comes a horn.

Pending the arrival of that twelve or twenty drawer cabinet, the beginner will probably be content to arrange his specimens in boxes. A handy sized box is one measuring 14 inches by 10 when closed, and it should have a cell for naphthaline.

Before putting the specimens away into boxes or drawers [Pg 28]they should be labelled with the date of capture, the locality, the name of the captor, and any other detail of interest in connection with it. All these particulars may be written on small squares of paper and put on the pins under the specimens.

Cabinets or boxes containing insects should always stand where they are free from damp, otherwise mould may make its appearance on the specimens. Mouldy insects may be cleaned, but they never look nice afterwards; so it will be well to bear in mind that prevention is better than cure. Where drawers and boxes are not properly attended to in the matter of naphthaline, mites are apt to enter and cause injury to the specimens. If these pests should effect a lodgment, a little benzine poured on the bottom of box or drawer will quickly kill them. The benzine, if pure, will not make the least stain, and of course the drawer or box must be closed directly the benzine is put in. Do this only in the daytime.

Rearing butterflies from the egg is much practised, and is a very excellent way. One not only obtains specimens in fine condition, but gains knowledge of the early stages at the same time. The eggs of most of the Whites, the Orange-tip, the Brimstone, and some others are not difficult to obtain, but searching the food-plants for the eggs of many of the butterflies is tiresome work, and not altogether remunerative. Females may be watched when engaged in egg-laying, and having marked the spot, step in when she has left and rob the "nest." The best plan is to capture a few females and enclose them in roomy, wide-mouthed bottles, or a gauze cage, putting in with them a sprig or two of the food-plant placed in a holder containing water. The mouth of the bottle should be covered with gauze or leno, and a bit of moistened sugar put on the top outside. Either bottle or cage must be stood in the sunshine, but it must be remembered that the butterflies require plenty of air as well as sunshine, and that they can have too much of the latter.

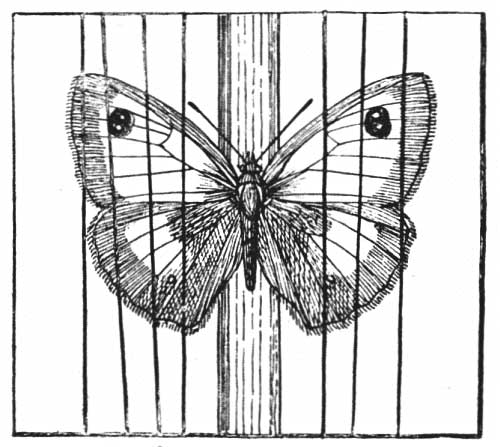

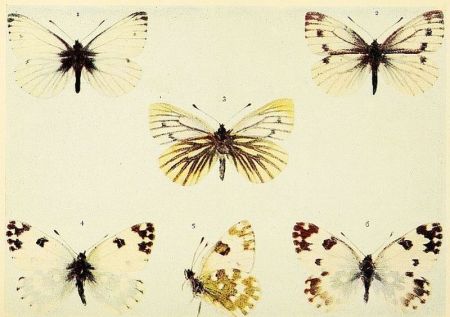

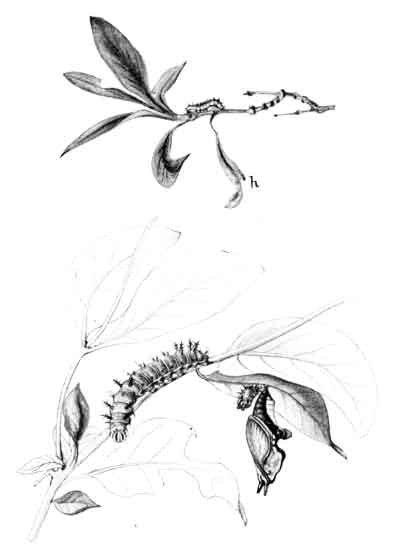

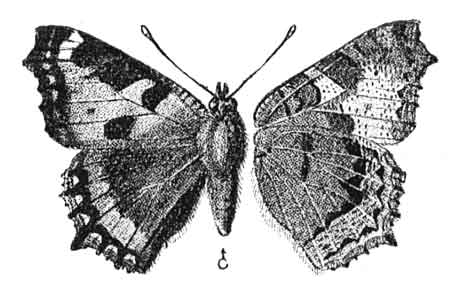

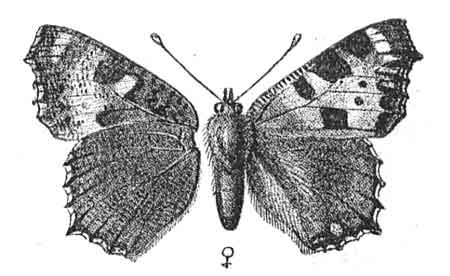

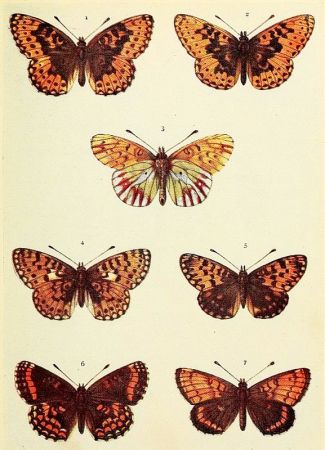

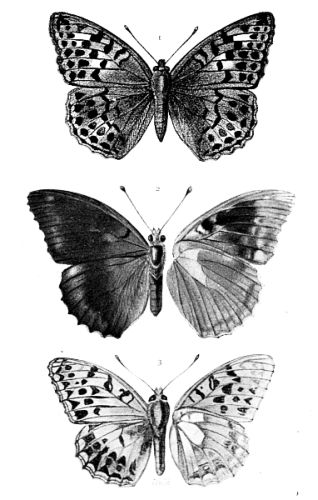

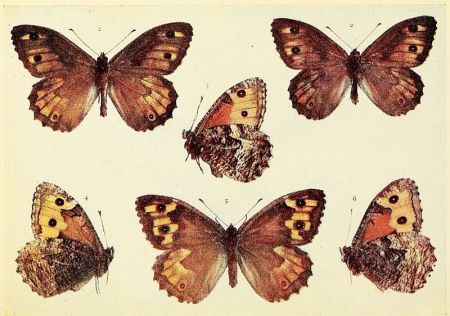

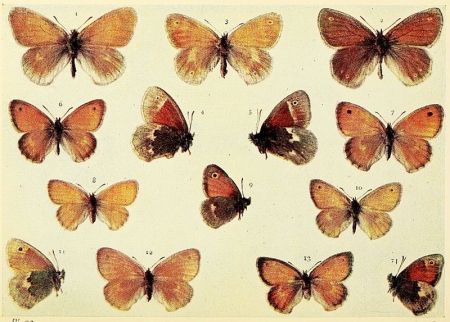

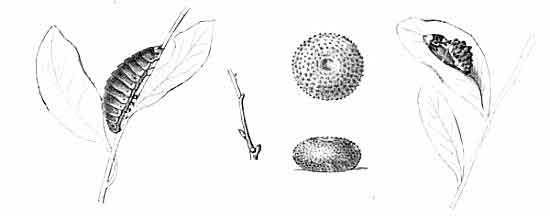

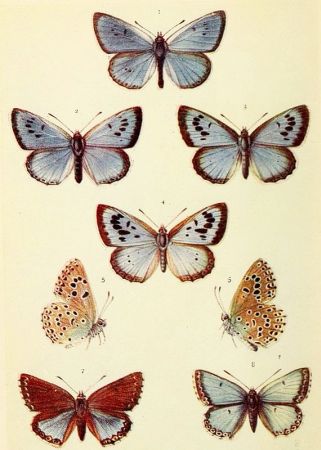

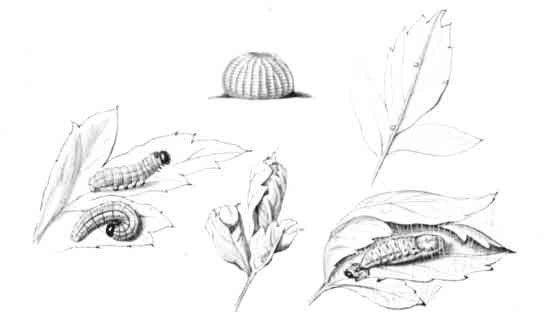

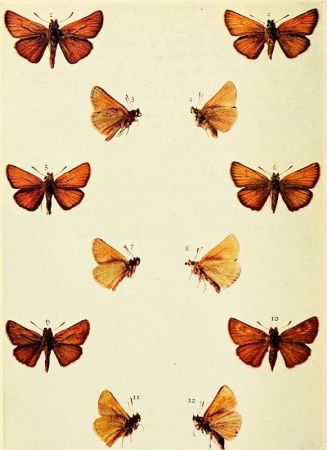

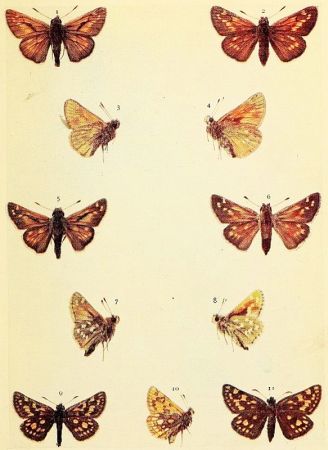

The Swallow-tail butterfly is the only British member of the extensive and universally distributed sub-family Papilioninæ, which includes some of the largest as well as the most handsome kinds of butterfly. Our species has yellow wings ornamented with black, blue, and red, and is an exceedingly attractive insect. The black markings are chiefly a large patch at the base of the fore wings, this is powdered with yellow scales; a band, also powdered with yellow, runs along the outer or hind portion of all the wings. There are also three black spots on the front or costal margin, and the veins are black. The bands vary in width, and that on the hind wings is usually clouded more or less with blue. At the lower angle of the hind wings there is a somewhat round patch of red, and occasionally there are splashes of red on the yellow crescents beyond the band. The male and female are shown on Plate 2.

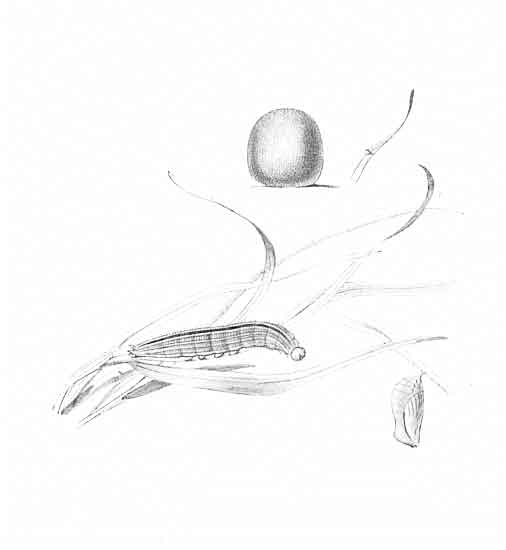

The eggs are laid on leaflets of the milk parsley (Peucedanum palustre), which in the fenny home of the butterfly is perhaps the chief food-plant of the caterpillar. This is one of the few eggs of British butterflies that I have not seen. Buckler says that it is globular in shape, of good size, greenish yellow in colour when first laid, quickly turning to green, and afterwards becoming purplish.

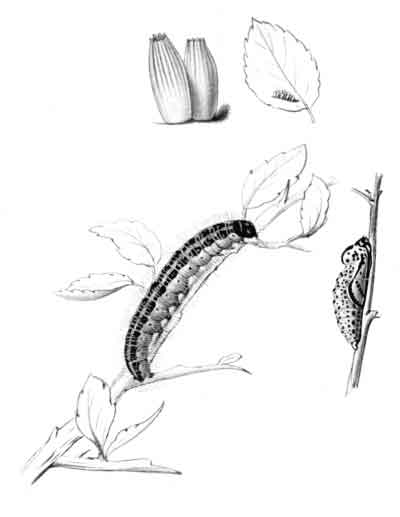

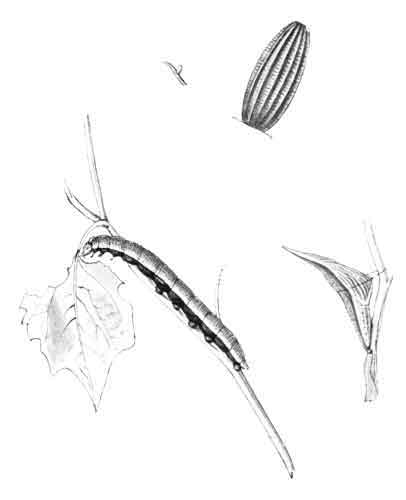

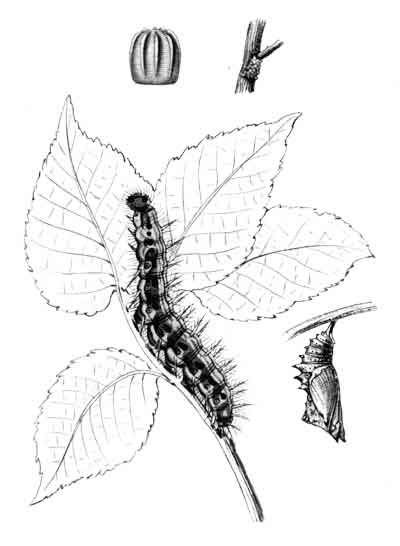

The caterpillar when full grown, as figured on Plate 1, is bright green with an orange-spotted black band on each ring of the body, and blackish tinged with bluish between the rings. The head is yellow striped with black. When it first leaves the egg-shell, which it eats, the caterpillar is black with a noticeable white patch about the middle of the body. After the third change of skin it assumes the green colour, and at the same time a remarkable V-shaped fleshy structure of a pinkish or orange colour is developed. This is the osmaterium, and is said to emit a strong smell, which has been compared to that of a decaying pine-apple. The organ, which is extended in the figure of the full-grown caterpillar, is not always in evidence, but when the caterpillar is annoyed the forked arrangement makes its appearance from a fold in the forepart of the ring nearest the head. Other food-plants besides milk parsley are angelica (Angelica sylvestris), fennel (Fœniculum vulgare), wild carrot (Daucus carota), etc. From eggs laid in May or June caterpillars hatch in from ten to twelve days, and these attain the chrysalis state in about six or seven weeks. If the season is a favourable one, that is fine and warm, some of the butterflies should appear in August, the others remaining in the chrysalids until May or June of the following year; a few may even pass a second winter in the chrysalis. Caterpillars from eggs laid by the August females may be found in September, nearly or quite full grown, and chrysalids from October onwards throughout the winter. They are most frequently seen on the stems of reeds, but they may also be found on stems or sprays of the food-plants, as well as on bits of stick, etc. It would, however, be practically useless to search for the late chrysalids as the reeds are usually cut down in October, when the fenmen keep a sharp look-out for them, and few are likely to escape detection in any place that would be accessible to the entomologist.

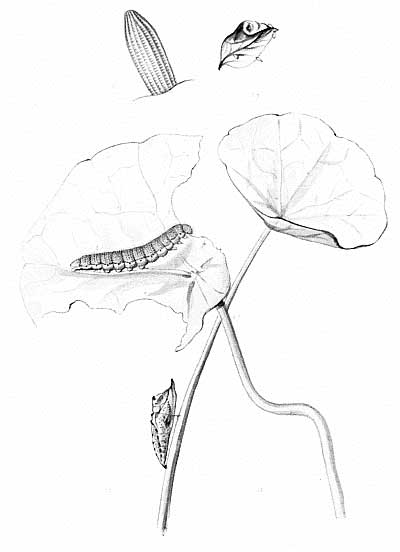

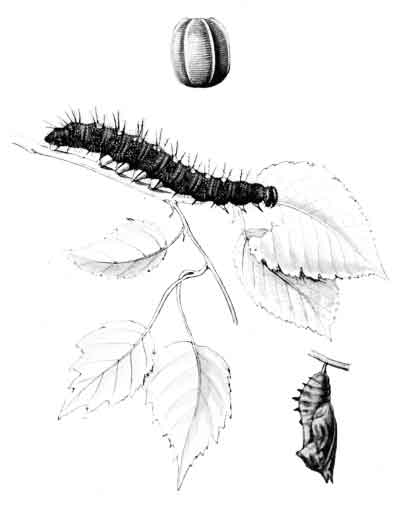

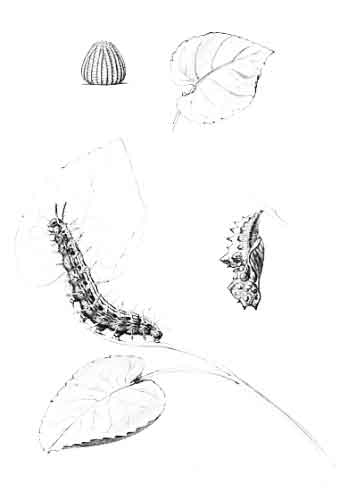

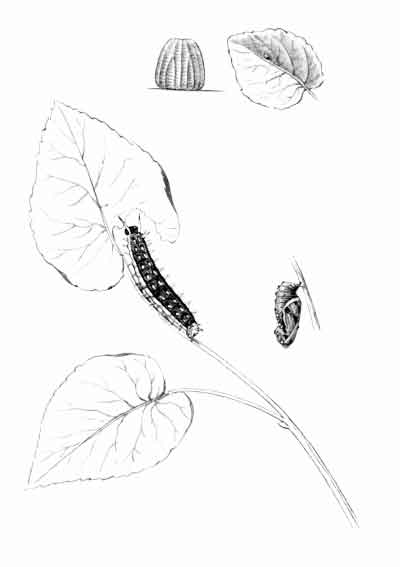

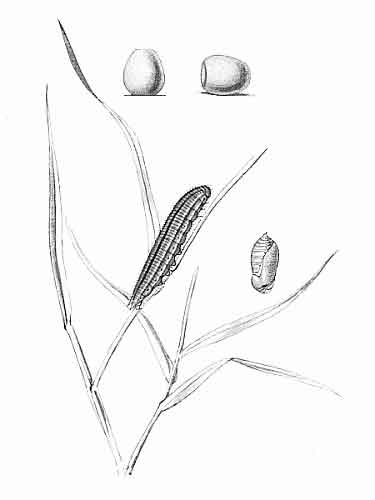

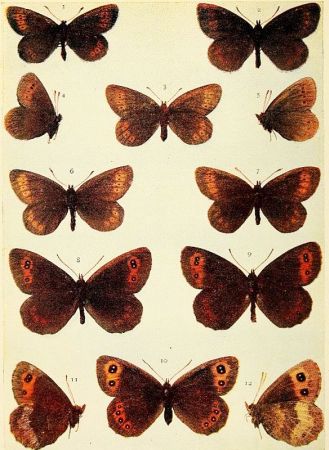

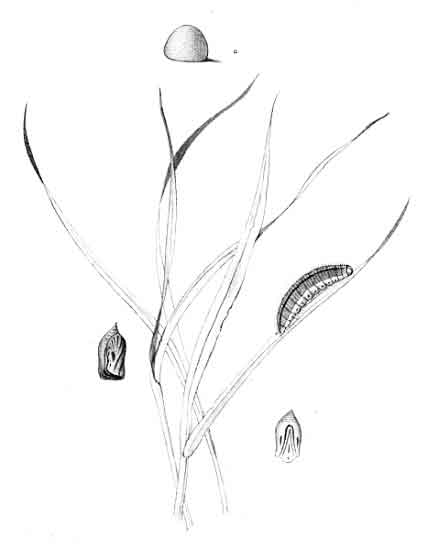

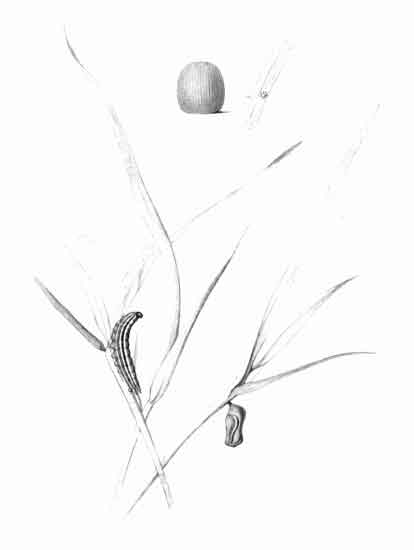

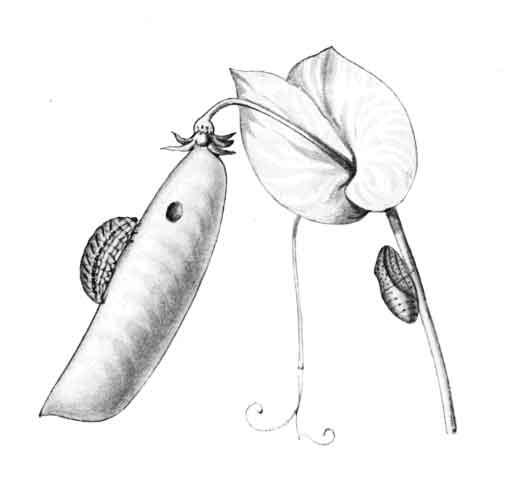

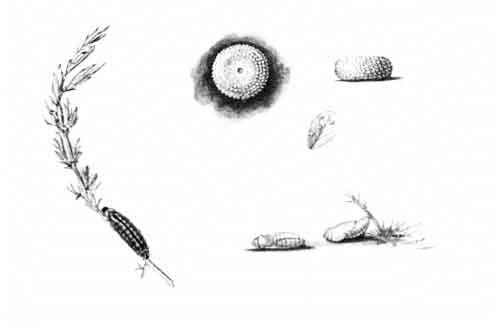

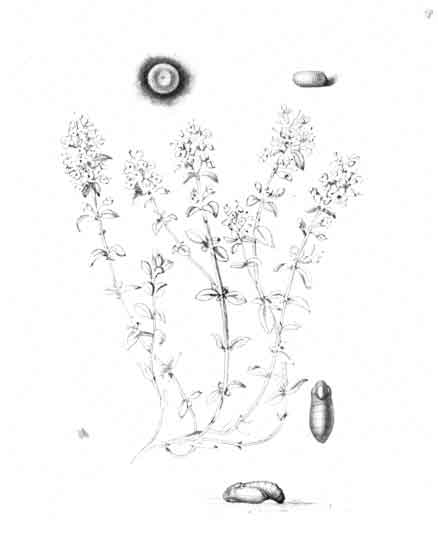

Pl. 3.

Black-veined White Butterfly.

Eggs, natural size and enlarged; caterpillar and chrysalis.

On Plate 1 three forms of the chrysalis are shown. The figures are drawn from specimens collected in Wicken Fen in October, 1905. Occasionally a much darker, nearly black, form is found.

This butterfly was known to Petiver and other early eighteenth-century entomologists as the Royal William. There is every reason to believe that at one time it was far more widely distributed in England than it now is. Stephens, writing in 1827, states that it was formerly abundant at Westerham, and gives several other localities, some very near to London.

During the last twenty-five years or so, the butterfly has been seen on the wing, from time to time, in various parts of the Southern and Midland counties. Caterpillars have also been found at large in Kent. Possibly attempts may have been made to establish the species in certain parts of England, and the presence of odd specimens in strange places may thus be accounted for. Or such butterflies may have escaped from some one who had reared them.

On the Continent the butterfly is common in woods as well as in meadows, and even on mountains up to an elevation of 5000 feet. It occurs also, but less commonly, at much higher altitudes. It therefore seems strange that in England it should be confined to the low-lying fens of Norfolk and Cambridgeshire. Such is the case, however, and a journey to one or other of its localities will have to be made by those who wish to see this beautiful creature in its English home.

It may be added that the geographical range of the butterfly extends eastwards through Asia as far as Japan. A form, known as the Alaskan Swallow-tail, is found in Alaska.

The following ten species belong to the Pierinæ, another sub-family of Papilionidæ.

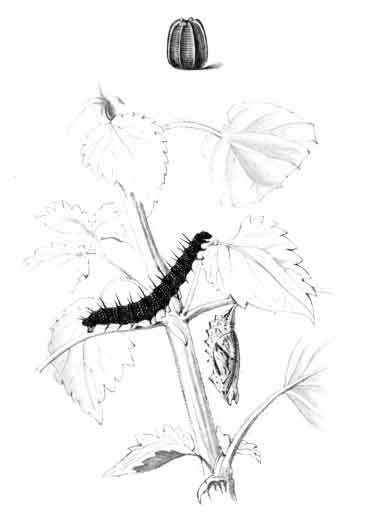

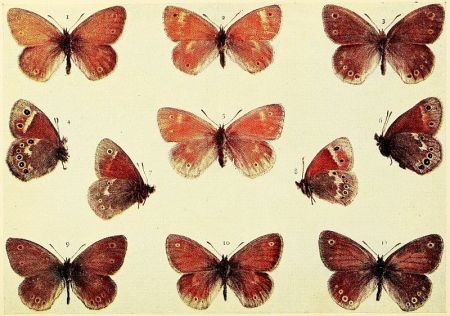

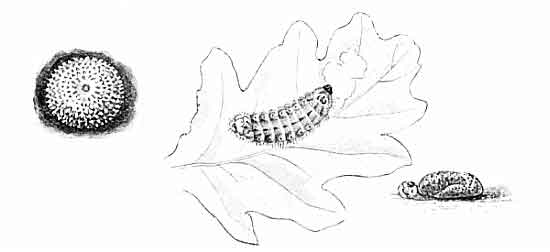

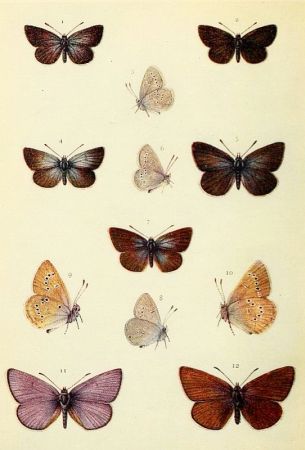

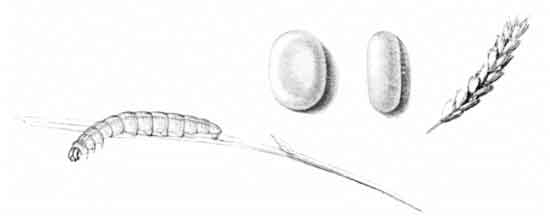

The Black-veined White (Plate 4) may be at once recognized by its roundish white wings and their conspicuous veins, which latter are black in the male butterfly, and in the female brownish on the main ones (nervures) and black on the branches (nervules). As the scales on the wings are denser in the male than in the female, the former always appears to be the whiter insect. On the outer margin of the fore wings there are more or less triangular patches of dusky scales, and these in occasional specimens are so large that their edges almost or quite meet, and so form an irregular, dusky border to the fore wings. These patches are also present on the hind wings, but are not so well defined. Sometimes the patches are absent from all the wings. The fringes of the wings are so short that they appear to be wanting altogether. The early stages are figured on Plate 3.

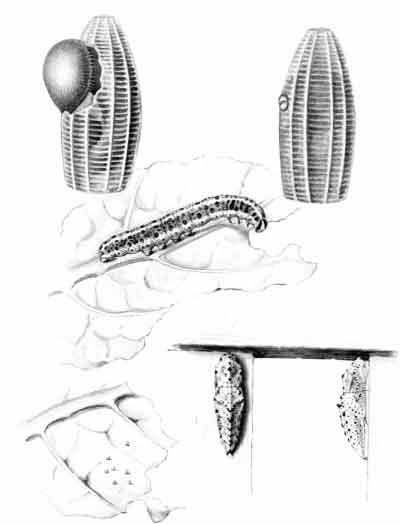

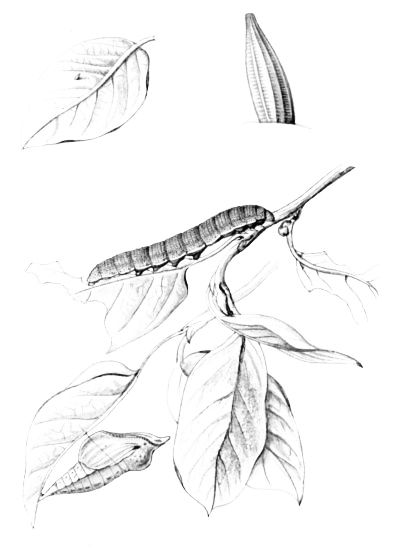

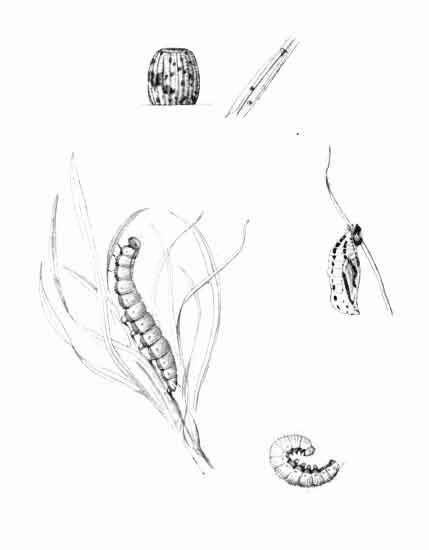

The egg is upright and ribbed from about the middle to the curiously ornamented top, which appears to be furnished with a sort of coronet. The colour is at first honey-yellow, then darker yellow, and just before the caterpillar hatches, greyish. The eggs are laid in a cluster on the upper side of a leaf of sloe, hawthorn, or plum, etc., in the month of July.

The caterpillar when full grown is tawny brown with paler hairs arising from white warts; the stripes along the sides and back are black. The under parts are greyish. The head, legs, and spiracles are blackish. Caterpillars hatch from the egg in August, and then live together in a common habitation which is formed of silk and whitish in colour. They come out in the morning and again in the evening to feed, but a few leaves are generally enclosed in their tenement. In October they seem to retire for the winter and reappear in the spring. During May they become full grown and then enter the [Pg 33]chrysalis state. The butterflies are on the wing at the end of June and in July.

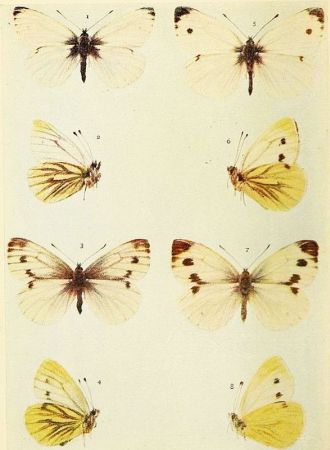

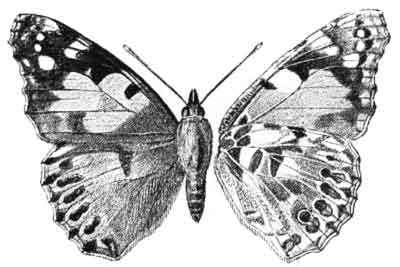

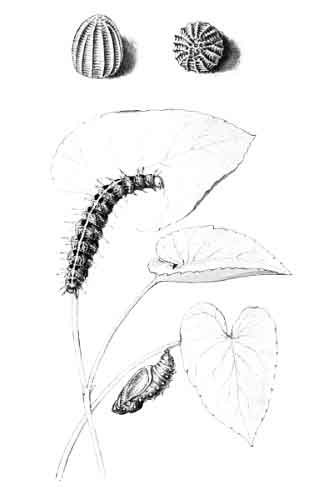

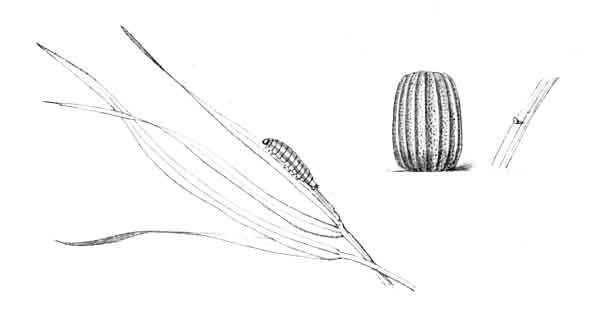

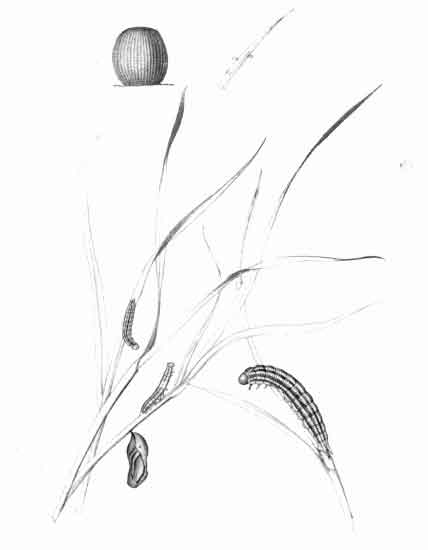

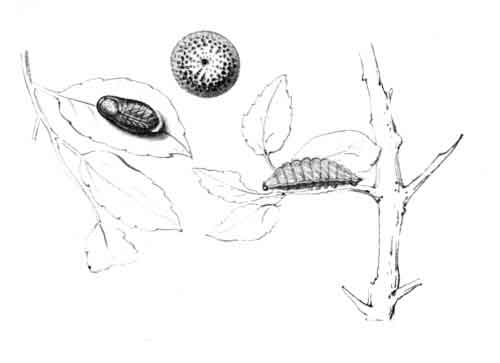

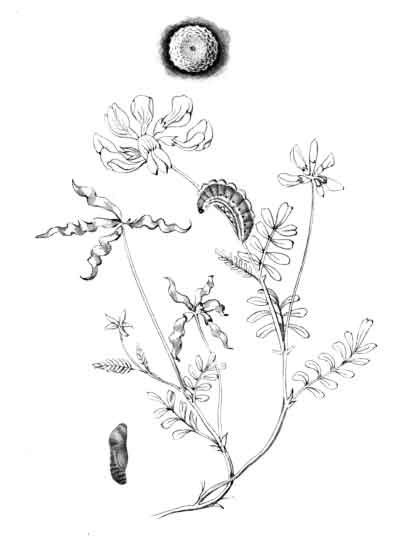

Pl. 5.

Large White Butterfly.

Eggs, natural size and enlarged; caterpillar and chrysalids.

The chrysalis is creamy white, sometimes tinged with greenish, and dotted with black.

This butterfly was mentioned as English by Merret in 1667, and by Ray in 1710. Albin in 1731, who wrote of it as the White Butterfly with black veins, figures the caterpillar and the chrysalis, and states that caterpillars found by him in April turned to chrysalids early in May and to butterflies in June. Moses Harris in 1775 gave a more extended account of the butterfly's life-history, and what he then wrote seems to tally almost exactly with what is known of its habits to-day. This species has seemingly always been somewhat uncertain in its appearance in England. Authors from Haworth (1803) to Stephens (1827) mention Chelsea, Coombe Wood in Surrey, and Muswell Hill in Middlesex, among other localities for the butterfly. It has also been recorded at one time or another, between 1844 and 1872, from many of the Midland and Southern counties. In 1867 it was found in large numbers, about mid-summer, in hay fields in Monmouthshire. The latest information concerning the appearance of the species in South Wales relates to the year 1893, when several caterpillars and four butterflies were noted on May 22 in the Newport district. At one time it was not uncommon in the New Forest, but no captures of the butterfly in Hampshire have been recorded during the last quarter of a century. At the present time it is probably most regularly obtained in a Kentish locality, presumably in the Isle of Thanet, which is only known to a few collectors. It may be mentioned that some thirty years ago caterpillars of the Black-veined White could be obtained from a Canterbury dealer at a few shillings per gross.

The species is widely distributed, and often abundant, on the Continent, and its range extends through Western and Northern Asia to Yesso, Northern Japan.

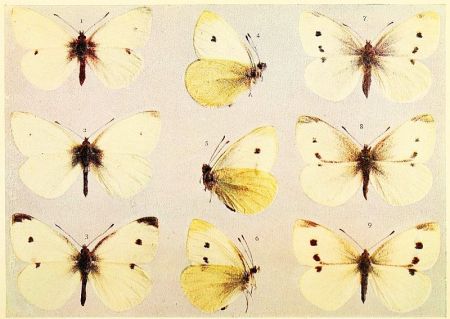

This butterfly is probably almost as familiar to those who dwell in towns as it must be to those who live in the country. It is perhaps unnecessary to describe it in any detail, and it may therefore suffice to say that it is white with rather broad black tips to the fore wings; there are some black scales along the front margin of these wings, and on the basal area of all the wings. The male has a black spot on the front margin of the hind wings, and the female has, in addition, two roundish black spots on the fore wings, with a black dash from the lower one along the inner margin.

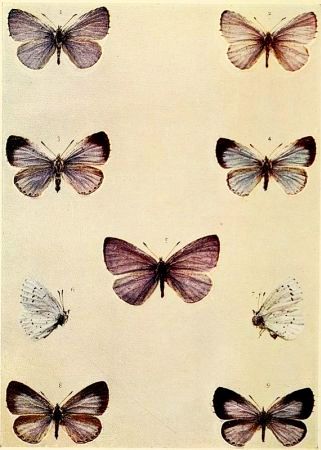

As there is a rather important difference between the specimens of the spring (vernal) and the summer (æstival) broods, figures of a male and a female of each brood, and showing the upper and under sides, are given. Those on Plate 6 represent the spring form, which was at one time considered to be a distinct species, and named chariclea by Stephens. Plate 9 shows the summer form. The chief point of difference is to be noted in the tips of the fore wings, which in the spring butterflies are usually, but not invariably, greyish; in the summer butterflies the tips are black, as a rule, but not in every case.

Occasionally the black on tip of the fore wing in the female is increased in width, and from it streaks project inwards towards the upper discal spot. In some examples of the male there is a more or less distinct blackish spot on the disc of the fore wings. Very rarely the ground colour is creamy or sulphur tinted.

The greenish tinge about the veins, sometimes seen in these butterflies, is due to some accidental cause, probably injury to the veins.

Pl. 7.

Small White Butterfly

Resting.

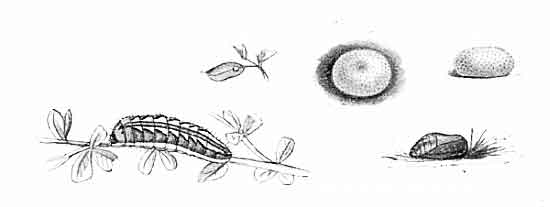

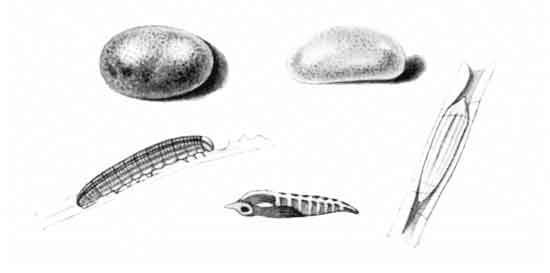

The egg is yellowish in colour, somewhat skittle-shaped, and very prettily ribbed and reticulated. On Plate 5 there are two figures of the egg from enlarged drawings by Herr Max Gillmer, to whom I am greatly indebted for the loan of them. In the figure on the right, the dark spot at the shoulder of the egg represents the head of the young caterpillar, and in that on the left is seen the caterpillar about to come out of the egg. The head is already out, and the jaws have left their mark on the egg-shell. Most caterpillars of the Whites, as well as those of other butterflies, devour their egg-shells.

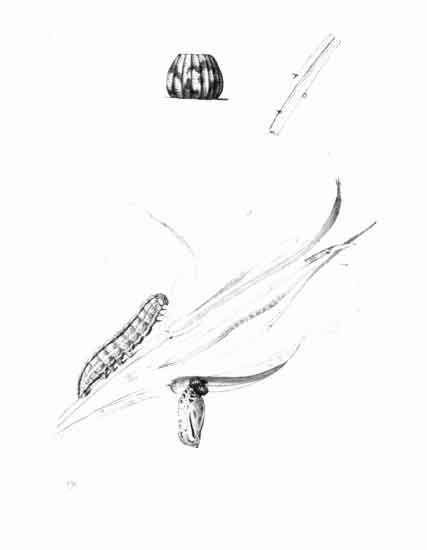

The eggs are laid in batches of from six to over one hundred in each batch. They are placed on end, and on either side of a leaf, chiefly cabbage. Herr Gillmer writes that he watched a female depositing her eggs on a leaf of white cabbage in the hot sunshine, and found that she laid twenty-seven in about nine minutes. A previous observer had timed a female, and noted that she produced eggs at the rate of about four in the minute. Caterpillars hatch from the egg in about seven days in the summer. The caterpillar (Plate 5) when full grown is green tinged with blue or grey above, and greenish beneath. There are numerous short whitish hairs arising from little warts on the back and sides; the lines are yellow. The caterpillars feed in July, and sometimes again in September and October, on all plants of the cabbage tribe, and also on tropæolum and mignonette. A number of these caterpillars may often be seen crowded together on a cabbage leaf, and they sometimes abound to such an extent that much loss is sustained by growers of this most useful vegetable. A peculiarity of these caterpillars is that even when not numerous, their presence is indicated by an evil smell that proceeds from them. The unpleasantness of the odour is greatly intensified if the caterpillars are trodden upon.

The chrysalis (Plate 5) is of a grey colour, more or less spotted with black and streaked with yellow. It is often to be seen fixed horizontally under the copings of walls, the top bar of a fence, or a window-sill; but it sometimes affects [Pg 36]the upright position when fastened in the angle formed by two pales. A position that affords some measure of protection from weather is generally selected.

Although this butterfly is almost annually to be seen, in greater or lesser numbers, throughout the country, it is occasionally scarce, either generally or in some parts of the British Islands. For example, during the past year (1905) it was abnormally plentiful in Ireland, but at the same time comparatively rare in England. It is a migratory species, and no doubt its abundance in any year in these islands is dependent on the arrival of a large number of immigrants. Possibly in some years none of the migrant butterflies reach our shores, and that it is largely to this failure the rarity of the species in such years is to be attributed. Caterpillars resulting from alien butterflies may absolutely swarm in the autumn of one year, but the eccentricities of an English winter may be too much for the vitality of such of them as escape their enemies, Apanteles glomeratus, and other so-called "ichneumons," and reach the chrysalis state. So, with immigration on the one hand and destructive agencies on the other, it may be understood how it comes about that the Large White is sometimes abundant and sometimes scarce.

This species seems to range over the whole of the British Islands, with the exception, perhaps, of the Shetlands. Abroad, it has been found in all parts of the Palæarctic Region, except the extreme north, and Eastern Asia.

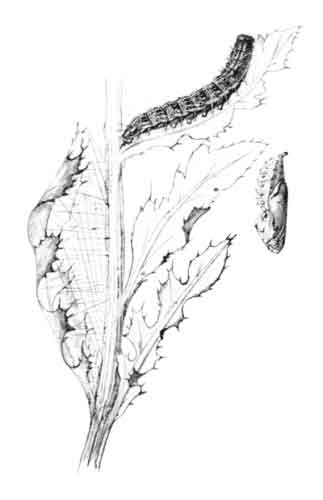

The Small White butterfly (Plate 11) is, perhaps, more often in evidence then its larger kinsman just referred to. It also is a migrant, and although it never seems to be absent from these islands, in its proper season, its great increase in numbers in some years is almost certainly due to the arrival of immigrants.

The spring form of this butterfly, named metra by Stephens, who, together with others, considered it a good species, has the tips of the fore wings only slightly clouded with black; and the black spots near the centre of the wings are always more or less faint in the male. Sometimes the central spot and also the blackish clouding of the tip are entirely absent. The summer brood, on the other hand, has fairly blackish tips and distinct black spots—one in the male and three in the female, the lower one lying on the inner margin. Occasionally examples of this flight bear a strong resemblance to the Green-veined White, the next species. The wings are sometimes, chiefly in Ireland, of a creamy colour, more especially in the female, or, more rarely, of a yellowish tint. In North America, where this species was accidentally or intentionally introduced some years ago, bright yellow forms are not uncommon in some localities, and the variety is there known as novangliæ.

In certain favourable years a partial third brood has occurred, but such specimens are often small in size.

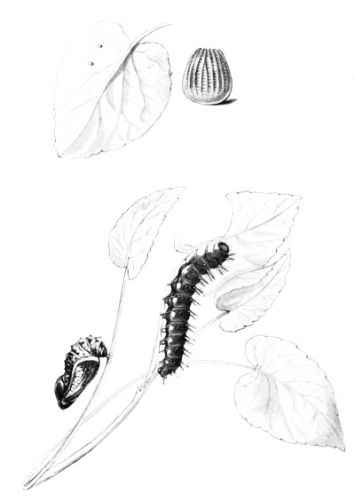

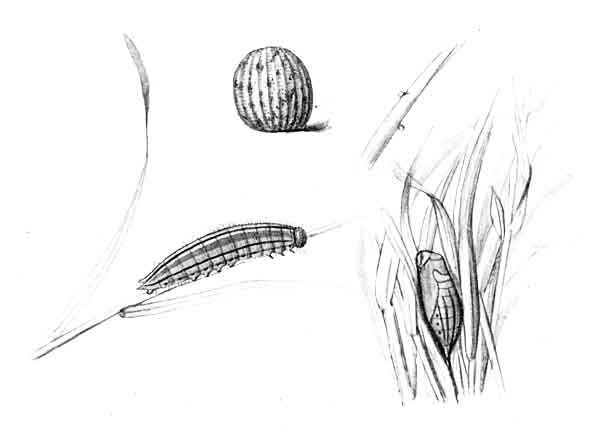

The egg (Plate 8) is at first pale greenish, but later on it turns yellowish, and this tint it retains until just before the caterpillar hatches out.

The caterpillar when full-grown has a brownish head and a green body; the latter is sprinkled with black and clothed with short blackish hairs emitted from pale warts. There is a yellowish line on the back, and a line formed of yellow spots on the side. It feeds on most plants of the cabbage tribe, and in flower gardens on mignonette and nasturtiums. It is often attacked by parasites, and especially by the Apanteles, referred to as destructive to caterpillars of the Large White.

The chrysalis may be of various tints, ranging from pale brown, through grey to greenish; the markings are black, but these are sometimes only faint. It is to be found in [Pg 38]similar situations to those chosen by the caterpillar of the last species, but often under the lower rail of a fence or board of a wooden building. Where caterpillars have been feeding in a garden, they often enter greenhouses, among other places, to pupate; and where these structures are heated during the winter, the butterflies sometimes emerge quite early in the year. Distributed throughout the British Islands, except the Hebrides and Shetlands. It is common over the whole of Europe, and extends through Asia to China and Japan. In America, where it was introduced into the United States some forty-five years ago, it has now spread northwards into Canada, and also southwards.

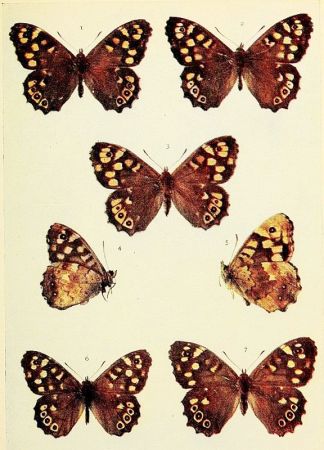

This butterfly is not often seen away from its favourite haunts in the country; these are woods, especially the sunny sides, leafy lanes, and even marsh land. As in the case of the two Whites previously noticed, there are always two broods in the year. The first flight of the butterflies is in May and June, occasionally as early as April in a forward season. These specimens have the veins tinged with grey and rather distinct, but are not so strongly marked with black as those belonging to the second flight, which occurs in late July and throughout August. This seasonal variation, as it is called, is also most clearly exhibited on the under side. In the May and June butterfly (Plate 13, left side) the veins below are greenish-grey, and those of the hind wings are broadly bordered also with this colour. In the bulk of the July and August specimens (Plate 13, right side) only the nervures are shaded with greenish-grey, and the nervules are only faintly, or not at all, marked with this colour.

Now and then a specimen of the first brood may assume the characters properly belonging to the specimens of the second brood; and, on the other hand, a butterfly of the second brood [Pg 39]may closely resemble one of the first brood. As a rule, however, the seasonal differences referred to are fairly constant. By rearing this species from the egg it has been ascertained that part (sometimes the smaller) of a brood from eggs laid in June attains the butterfly stage the same year, and the other part remains in the chrysalis until the following spring, the butterflies in each set being of the form proper to the time of emergence.

Pl. 8.

Small White Butterfly.

Eggs, natural size and enlarged; caterpillar and chrysalids.

The strongly-marked specimens (Plate 14) are from Ireland, and are of the first or spring brood. The seasonal variation in this species is not so well defined in Ireland as in England.

A form of variation in the female, and most frequent perhaps in Irish specimens, is a tendency of the spots on the upper side of the fore wings to spread and run together, and so form an interrupted band.

Specimens with a distinct creamy tint on the wings are sometimes met with, but such varieties, as well as yellow ones (var. flava, Kane), are probably more often obtained in Ireland and Scotland than in England. Occasionally male specimens of the second brood have two black spots on the disc of the wing. Some forms of this butterfly have been named, and these will now be referred to.

Sabellicæ (Petiver), Stephens, has been considered as a species distinct from P. napi, L. Stephens ("Brit. Entom. Haust.," I. Pl. iii., Figs. 3, 4) figured a male and a female as sabellicæ, which he states differs from napi in having shorter and more rounded yellowish-white wings. No locality or date is given in the text (p. 21) for the specimens figured; but referring to another example which he took at Highgate on June 4, he says that it agrees with his Fig. 2. Probably, however, it was his second figure that he intended, the Fig. 4 of the plate, which is a female. This is rather more heavily marked with dusky scales than is usual in specimens of the first brood, at least in England, although it agrees in this respect with some Irish June examples. [Pg 40]Fig. 3 represents a male which certainly seems to be referable to the spring form. Most authors give sabellicæ; as belonging to the summer flight, but this does not seem to be correct.

Var. napææ is a large form of the summer brood, occurring commonly on the Continent, in which the veins on the under side of the hind wings are only faintly shaded with greenish-grey. Occasionally specimens are taken in this country in August, which both from their size and faint markings on the under side seem to be referable to this form.

Var. bryoniæ is an Alpine form of the female, and in colour is dingy yellow or ochreous, with the veins broadly suffused with blackish grey, sometimes so broadly as to hide the greater part of the ground colour. This form does not occur in any part of the British Islands, but some specimens from Ireland and from the north of Scotland somewhat approach it.

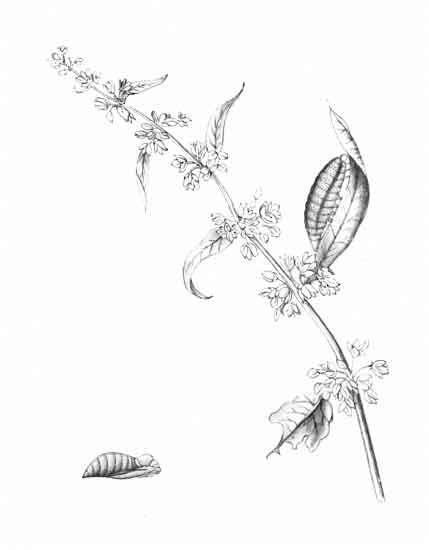

All the early stages are shown on Plate 10.

The egg is of a pale straw colour when first laid, but it soon turns to greenish, and as the caterpillar within matures, the shell of the egg becomes paler. The ribs seem to be fourteen in number.

The eggs are laid singly on hedge garlic (Sisymbrium alliaria) and other kinds of plants belonging to the Cruciferæ. The egg in the illustration was laid on a seed-pod of hedge garlic, but the caterpillar that hatched from it was reared on leaves of garden "nasturtium" and wallflower.

The caterpillar when full grown is green above, with black warts, from which arise whitish and blackish hairs. There is a darker line along the back, and a yellow line low down on the sides. Underneath the colour is whitish-grey. The spiracular line is dusky, but not conspicuous, and the spiracles are blackish surrounded with yellow. It has been stated that caterpillars fed upon hedge garlic and horseradish produce light butterflies, and that those reared on mignonette and watercress produce dark butterflies. Barrett mentions having reared a[Pg 41] brood of the caterpillars upon a bunch of watercress placed in water and stood in a sunny window, but he does not refer to anything peculiar about the butterflies resulting therefrom. He states, however, that from eggs laid in June the earliest butterfly appeared within a month, and the remainder by the middle of August, only one remaining in the chrysalis until the following June.

Pl. 10.

Green-veined White Butterfly.

Eggs, natural size and enlarged; caterpillar and chrysalis.

Pl. 11.

Small White Butterfly.

1, 2, 4 male (spring), 3 do. (summer); 5, 7, 8 female (spring),

6, 9, do. (summer).

Caterpillars may be found in June and July and in August and September.

The chrysalis is green in colour, and the raised parts are yellowish and brown. This is the most frequent form, but it varies through yellowish to buff or greyish, and is sometimes without markings.

Generally distributed throughout the British Islands, but its range northwards does not seem to extend beyond Ross.